As we absorb the news of Trump's victory in the US Presidential election, here’s a wrap compiled just before the result of what it might mean for climate action:

The UN Secretary General says the prospective departure of the United States would cripple the Paris Agreement, likening it to the loss of a limb or organ.

This analysis suggests that Trump (AND Harris if she had won) will focus on near-shoring or on-shoring of green technologies, ignore the WTO, and consider implementing a US carbon border mechanism, but opportunities for bi-lateral collaborations differed considerably between the candidates.

Action at State level maintained downward pressure on US emissions during the last Trump presidency, but could that work again if the IRA financing tap is turned off?

The looming chaos resulting from unpriced risk in the housing and asset markets will define the next presidency, according to Mother Jones.

That may be the biggest climate lesson for Aotearoa, where similar unpriced risk lurks just around the corner for an economy that is really just a housing market with bits tacked on. From the perspective of Hood’s (2011) politics of blame avoidance, the question of managed retreat must be made both highly visible and unavoidable if we want to see government action to limit the damage.

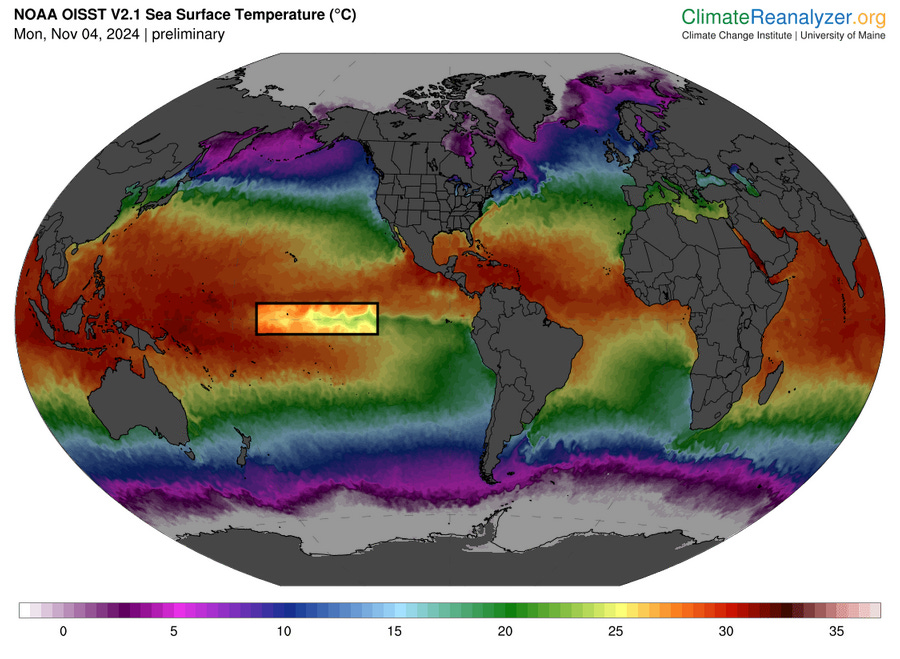

Chart of the week: La Niña , where art thou?

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the video and podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

1. A second Trump withdrawal could cripple the Paris Agreement

UN Secretary-General António Guterres has compared the prospective departure of the United States (US) from the landmark agreement to the loss of a limb or organ.

“The Paris agreement can survive, but people sometimes can lose important organs or lose the legs and survive. But we don’t want a crippled Paris agreement. We want a real Paris agreement,” the UN secretary general said. The Guardian.

It raises the prospect, according to the Guardian, of a domino effect, where the failure of international cooperation emboldens other countries to exit the agreement.

One could argue that the petrostate takeover of climate COPs (UAE last year and Azerbaijan this year) has already crippled the Paris Agreement and that progress is now shifting to bi-lateral and intergovernmental negotiations taking place outside of the UNFCCC framework, including via tax and trade institutions.

2. Approaches to transatlantic collaboration limited under Trump

This analysis before the election from the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) suggested that both candidates would have prioritised reshoring and nearshoring, including (or perhaps especially) with regard to green technologies, ignored the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and be increasingly amenable to a U.S. carbon border mechanism.

In negotiations with the U.S., they recommend that EU negotiators frame climate as a competitiveness issue when dealing with Trump (and as an ideological issue if they had been dealing with Harris). However, ambition for collaborative action will inevitably be more limited under a Trump presidency, meaning that progress beyond the UNFCCC could also be throttled.

3. Can action at State level help to maintain emissions reductions?

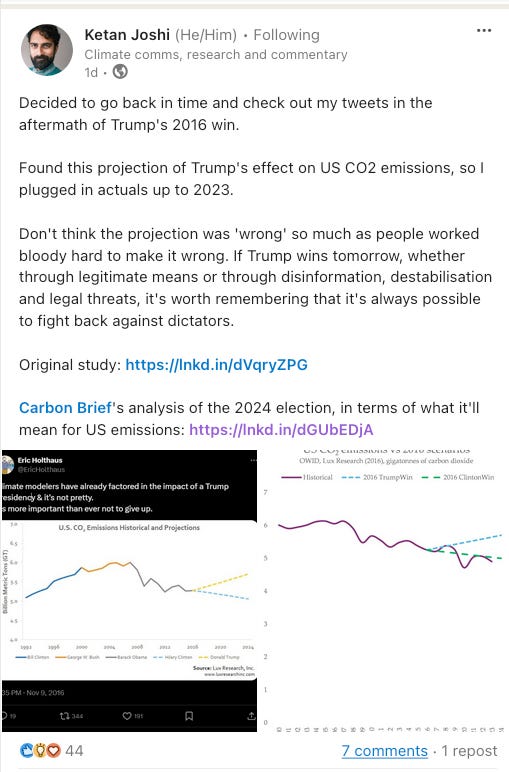

An argument frequently proffered is that some emissions declines are not easily reversible, and key states will continue to invest in climate action, even in the absence of federal support. This was certainly the case during the first Trump presidency, when the trajectory of emissions reductions was not affected as much as many feared. (Ketan Joshi reviewed his predictions from 2016 on Linkedin, below).

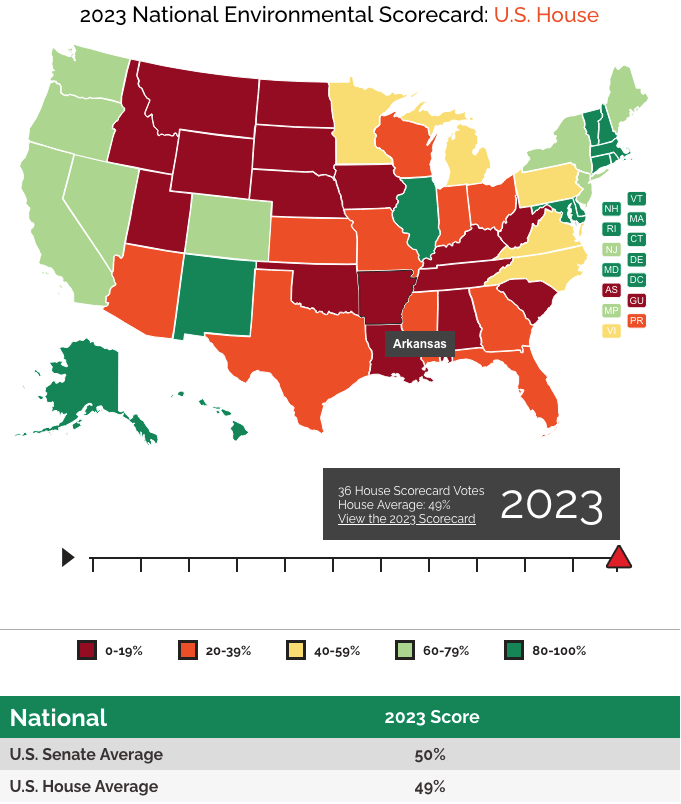

However, times have changed, and much of the accelerated action being taken by states today is funded by the federal government through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). That’s a tap that can be turned off and Trump has said it would be “an honour” to “immediately terminate” a law he called the “Green New Scam”. This analysis by the Wisconsin Examiner takes a detailed look at climate action plans in both red and blue states that could be upended by the election result. The League of Conservation Voters tracks the National Environmental Scorecard at both House and Senate level, and will be well worth keeping tabs on during the next presidential term.

The downward trend in U.S. GHG emissions might not be entirely reversed (some changes really are baked in), but it would certainly alter the steepness of the trajectory – by about 4bn tonnes by 2030, according to a Carbon Brief analysis.

A post-election analysis in Grist claims that a Trump win means the Planet loses.

“The results promise to upend U.S. climate policy: In addition to returning a climate denier to the White House, voters also gave Republicans control of the Senate, laying the groundwork for attacks on everything from electric vehicles to clean energy funding and bolstering support for the fossil fuel industry.

“We have more liquid gold than any country in the world,” Trump said during his victory speech, referring to domestic oil and gas potential. The CEO of the American Petroleum Institute issued a statement saying that “energy was on the ballot, and voters sent a clear signal that they want choices, not mandates.””

4. It’s too late for an ‘orderly transition’ anyway

According to Mother Jones, chaos ensues regardless of the election result, because of the vast amount of unpriced risk that is already lurking ominously, and steadily encroaching from dark pockets.

“Hundreds of millions of Americans are about to have an unexpected collision with planetary reality. We’re already seeing the impact on insurance and finance. Insurance depends on the ability to accurately price risk, to accurately measure future value. And the truth is, a big chunk of America is way riskier than we thought it was, and seriously overvalued.

A conservative estimate of the homeowner insurance gap is $1.6 trillion in uncovered risks. That’s mostly being borne by people who are relatively poor or live in acknowledged flood and fire zones. Everyone in the insurance industry expects that gap to grow, as risks metastasize and are priced into policies. Insurance eventually becomes too expensive for many to afford, even if it’s still available. For homeowners, skyrocketing premiums are too high. But insurers worry they can’t charge enough to keep up with increasing risk. From society’s perspective, these imperatives are increasingly incompatible. The climate crisis is, in effect, rendering entire communities and even regions uninsurable.

[...] This pricing of unacknowledged risk into our communities will be a watershed event that extends into nearly every kind of real estate and local industry. Ignored climate brittleness—the quality of being easily broken by weather extremes but hard to fix—is being exposed. And brittleness revealed means value lost”.

Voters faced a choice between disaster capitalism, in which fortunes are made through dodgy infrastructure repair, corrupt disaster relief and response, insurance scams and utility privatisation or a costly national retrofit.

“The scams won’t stop there. Parasites thrive in muddy water, and there will be plenty of chances to leech away whatever money is left in hard-hit communities, before a process of unofficial abandonment takes hold. In collapsing places, corporations can grift via security contracts and private emergency services.

A broken and paranoid America—splintered by the incapacity to agree on observable facts, or trust the institutions we depend on to solve major problems—tumbling into the worst version of a climate catastrophe: that’s a future almost too grim to contemplate.”

And that is possibly the biggest lesson for us here in Aotearoa, because we have an enormous amount of unpriced risk and some big decisions to make as well. Time is not on our side and, because our economy is basically a housing market with bits tacked on, the implications are even more profound.

The failure to adequately price climate risk in economic modelling haunts the financial system and may end up being the catalyst for either collapse or transformation. A big question is whether our institutions (including the institutions of democracy) are any better placed to bend, not break amidst the fallout, than those in the US.

5. Whatever did happen to that Expert Report on Coastal Retreat?

A reminder that the report from the Expert Working Group on Managed Retreat, commissioned following public consultation by the Ministry for the Environment in April and May 2022 to develop recommendations for policy design was delivered over a year ago now. Rather than use it to design policy, the report was shuffled onto another desk, that of the Finance and Expenditure Select Committee, to form part of its inquiry into Climate Adaptation.

That report was delivered on 1st October 2024. Amongst other things, they recommend that the government consider the Expert Working Group’s recommendations on Managed Retreat regarding the government’s role in planned retreat. So now we have a second report telling the Government to read the first report.

The Government has 60 days to respond in writing. When it does, it will be available on the Parliament website at this link.

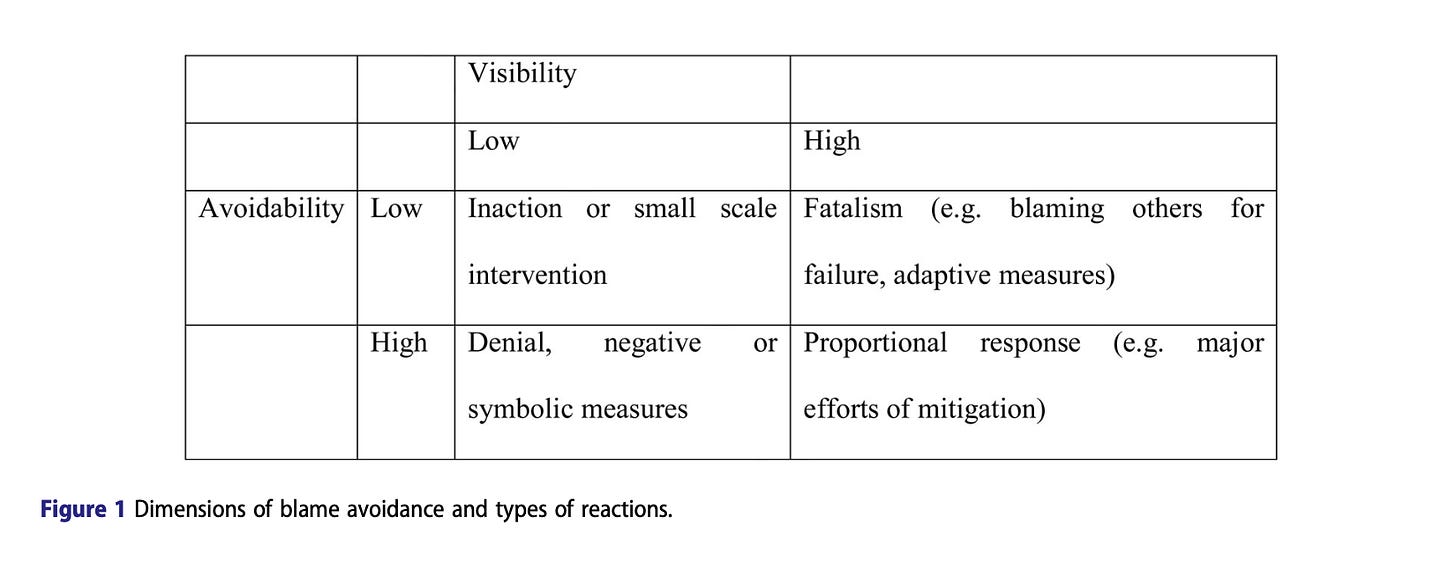

This is such a contentious and problematic issue that there is every chance the Government is going to absolutely avoid touching that for as long as they can. Disappearing or invisibilising the report is the first step. According to the politics of blame avoidance (The Blame Game, Christopher Hood), a government will react to a high-risk policy proposition according to two dimensions: visibility and avoidability. Howlett and Kemmerling (2017) created the following chart for climate change policymaking, based on Hood’s politics of blame avoidance:

So let’s make sure that report is highly visible and totally unavoidable.

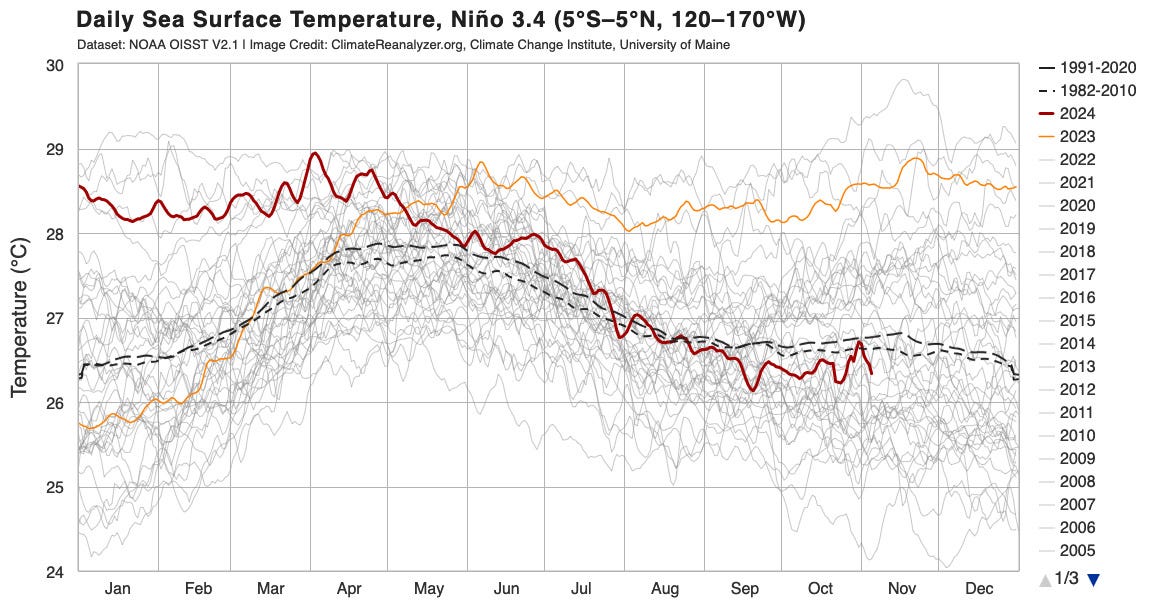

6. Chart of the week: La Niña, where art thou??

Whether El Niño, La Niña or neutral conditions prevail has a significant impact on the weather we experience in Aotearoa. They are collectively known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO. We are currently still on La Niña watch!

This chart measure the temperature in a very specific patch of the Pacific Ocean North-East of Aotearoa (see map below), and it tells us whether or not we are likely to have an El Nino or La Nina. The orange line shows last year’s El Nino, where sea surface temperatures soared above average in the Nĩno 3.4 patch. The red line shows this year’s surface ocean temperature. One of the criteria for a La Nina is the sea surface temperature in this patch of ocean dropping at least 0.8˚C below average. So far it has been tracking along in neutral territory, only slightly below average. Expectations that weak La Niña conditions would emerge this spring are currently on the wane.

Australia’s Bureau of Meterology (BOM) are the preeminent experts and have a great public page dedicated to the ENSO outlook. For more information on the effects of ENSO on weather in Aotearoa, see NIWA.

Finally, in other news this week, the biodiversity conference (COP16 in Cali, Colombia) made an important breakthrough on the subject of payment for the use of genetic information drawn from biodiversity. Half of the proceeds are to be distributed to indigenous peoples and local communities after a deal to create a permanent body for Indigenous and local communities was agreed. Here is a summary of progress made at the summit, and its implications for Aotearoa, from Toha’s Dr David Hall in Carbon News.

Ka kite ano

Bernard and Cathrine

Share this post