Long stories short, the top six things in our political economy around housing, climate and poverty on Monday, February 3 are:

Donald Trump unveiled 25% across-the-board tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada on Sunday, plus a new 10% across-the-board tariffs on imports from China;

Canada and Mexico hit back with their own tariffs and China warned it was considering similar measures, with Trump warning again he plans to slap tariffs on Europe and elsewhere;

The tariffs are much deeper and wider than in Trump’s first term, which economists say means the shock to supply chains globally is expected to slow economic growth and increase inflation for most large economies;

That higher global inflation and higher global interest rates adds a major headwind to the Government’s hopes for an economic and housing market recovery in 2025;

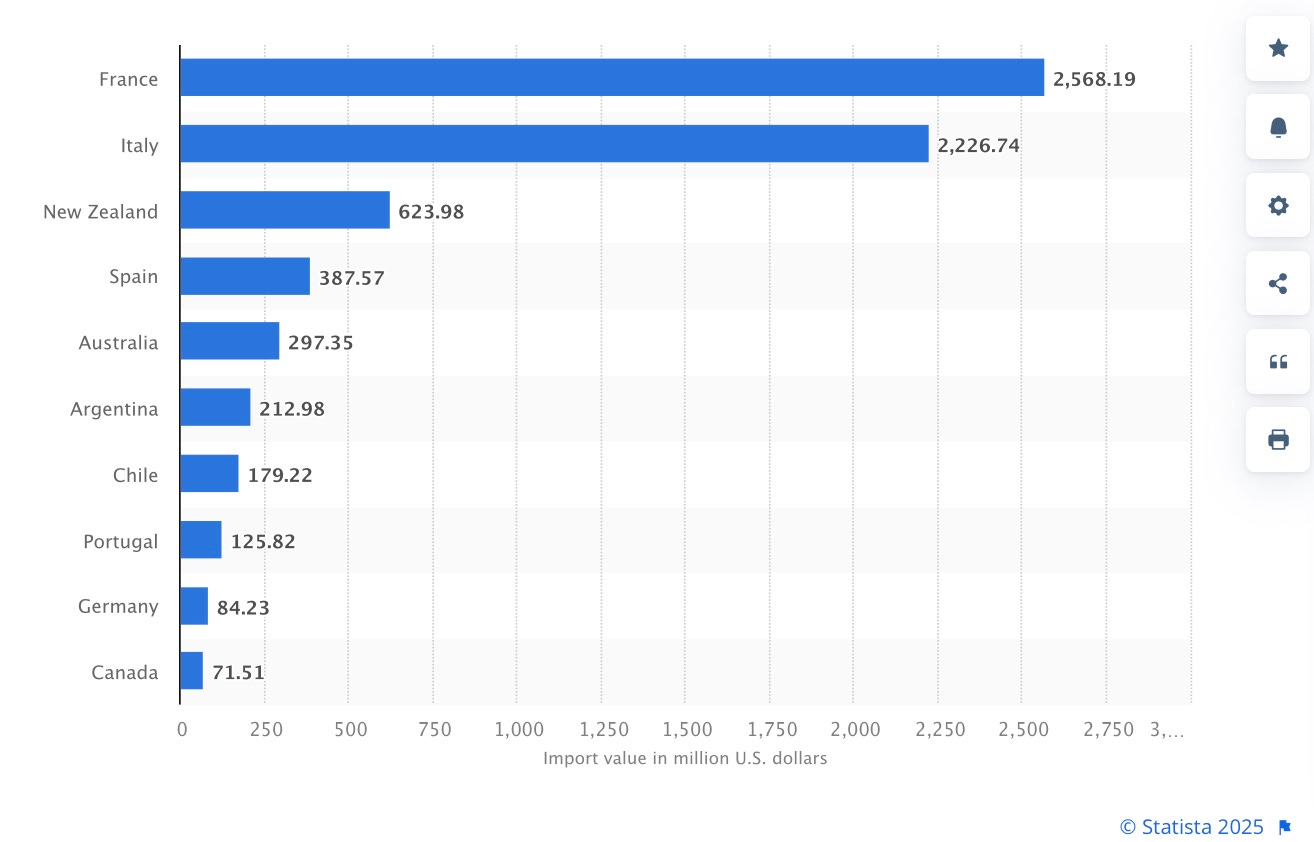

The impact will be messy, however, with some winners both here and overseas, including New Zealand’s beef and wine exporters to the United States, who may see their sales increase because Canada and Mexico are major exporters of beef to the United States1, while tariffs on European wine imports could help New Zealand, which is now the third largest source of wine imports to the United States; and,

The blanket tariffs are the biggest restriction to globalisation since the Second World War, which should force New Zealand’s political, diplomatic and business leaders to question baked-in and decades-long assumptions about ever-freer trade and whether we need to choose between a US-led trade and security bloc and a China-led one, or avoid picking one altogether.

(There is more detail, analysis and links to documents below the paywall fold and in the podcast above for paying subscribers. If we get over 100 likes from paying subscribers we’ll open it up for public reading, listening and sharing.)

Inside the biggest hit to globalisation in 70 years

The inevitable march of ever-freer trade powering ever-faster global economic growth and ever-lower inflation has been foundational in the thinking of our political, diplomatic and business leaders for 40 years, starting with our pre-emptive dropping of almost all tariffs and controls on imports from 1984-onwards.

The first big assumption was this would make most people richer and better-off, both globally and here in Aotearoa-NZ, and that this shift was inexorable, unavoidable and unquestionably good. The second big assumption was that the truth of the first assumption would push autocracies into democracies, in order to be part of the globalised rules-based trading system that gave consumers ever-cheaper goods and services and companies ever-richer consumers.

Those are still the base assumptions of our leadership class, even though the rest of the world’s voters, many of its leaders and plenty of economists concluded over the last decade that globalisation hasn’t worked for the middle classes of the world’s developed countries and has gutted their economies of the industrial bases needed to build weapons in any war.

Donald Trump’s imposition yesterday of 25% across-the-board tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada was by far the most important reversal of those broad globalisation trends and assumptions since the second world war. He also imposed a new 10% across-the-board tariff on imports from China and said he would also impose tariffs on Europe, in part to reduce America’s trade deficits with these trading partners. Canada immediately responded with tariffs on US$100 billion worth of US imports, while Mexico announced tariffs of its own, although with less detail. China threatened to respond with legal action in the World Trade Organisation.

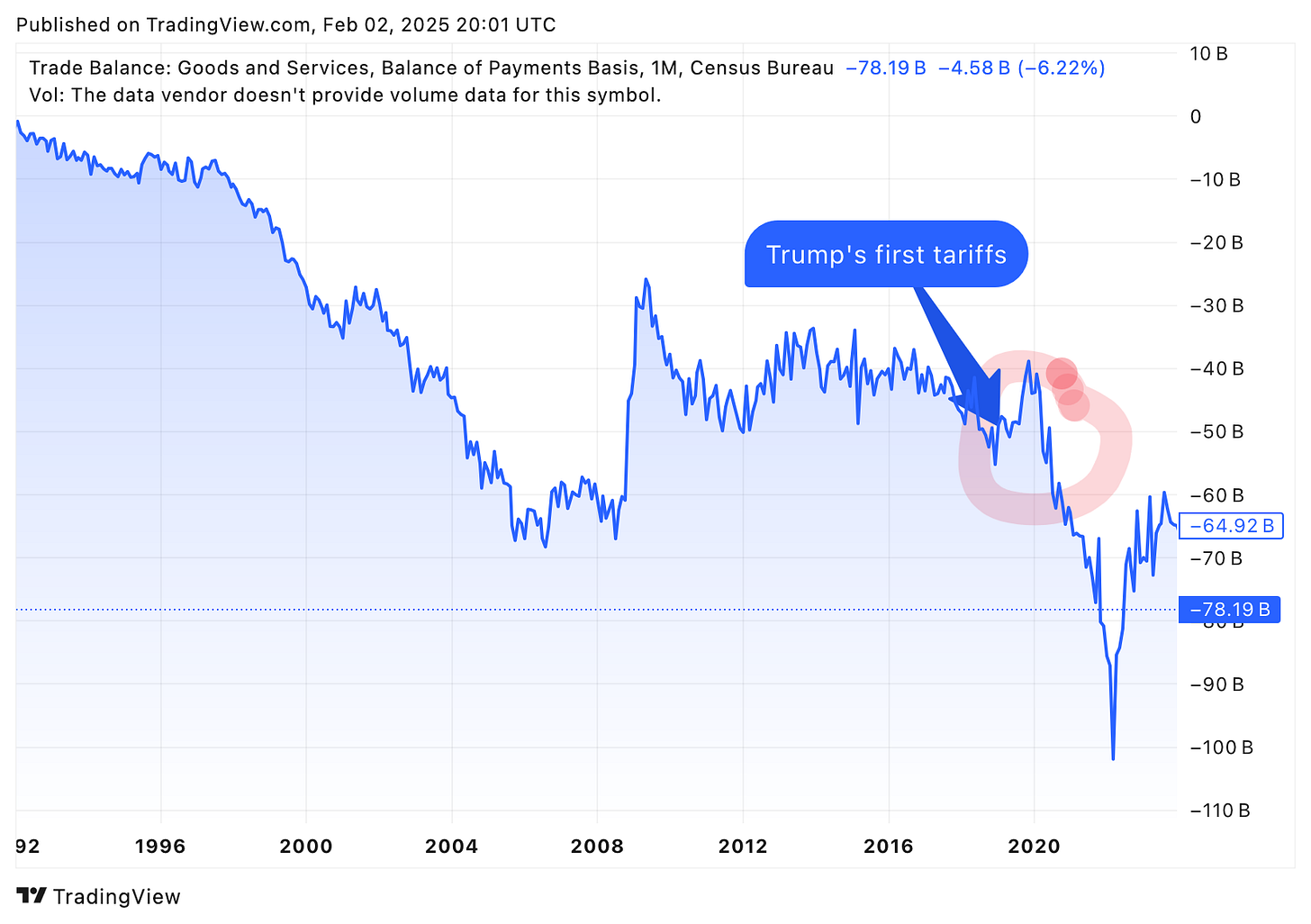

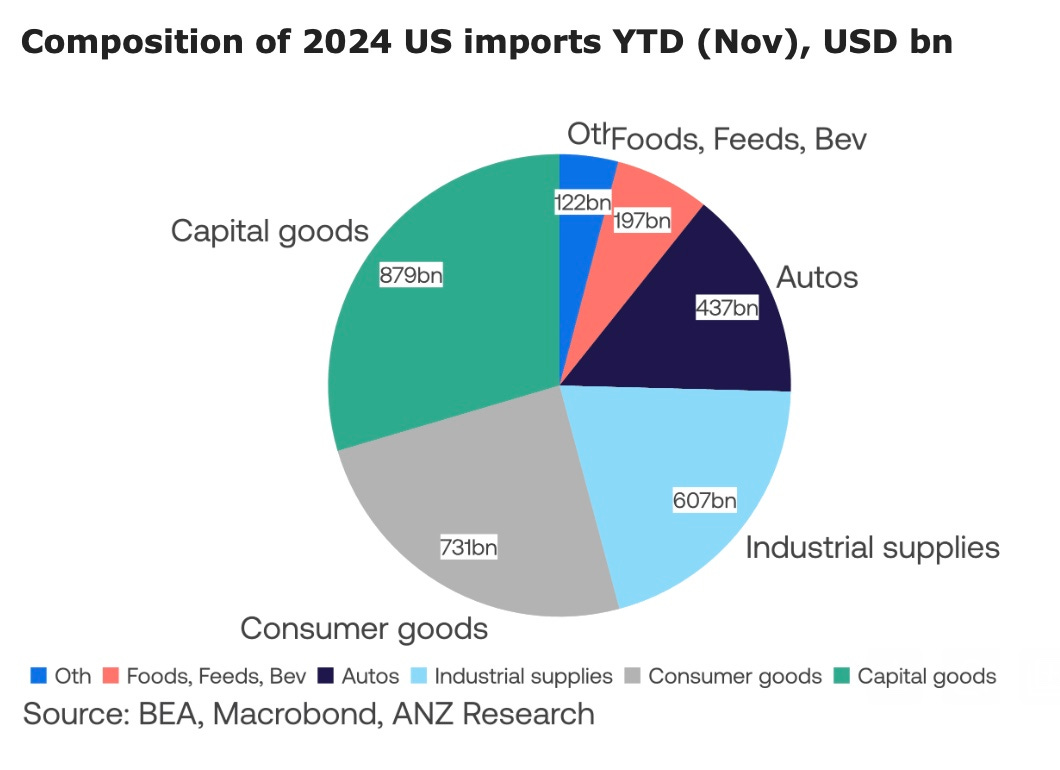

These are a much bigger deal than the piecemeal and targeted tariffs applied by Trump in 2018, and the scale of US trade with Canada, Mexico and China has also escalated since then. These three sources alone account for 42% of US imports and nearly 5% of GDP. If the 25% tariffs were passed on fully to US consumers, it would generate a one percentage point increase in US inflation in one quarter.

Trump’s first set of tariffs didn’t work to lower the US trade deficit

The other big concern is over half of US imports from Canada, Mexico and China are intermediate goods, which are added to other goods, often re-processed and re-exported to Canada, Mexico and China, before being re-processed there and exported again to America, with the tariff applied again.

Economists warned the disruption could represent a covid-like supply shock to global trade, which could again fire up inflation and slow economic growth.

John Llewelyn, partner at Independent Economics, a consultancy, and a former economist at the OECD, said that the main consequence of the tariffs would be inflation, with all countries likely to get hurt, including the US.

“The 80-year era of stability in the rules and conduct of economic and financial relations between countries ended today,” he said, via FT-$$$

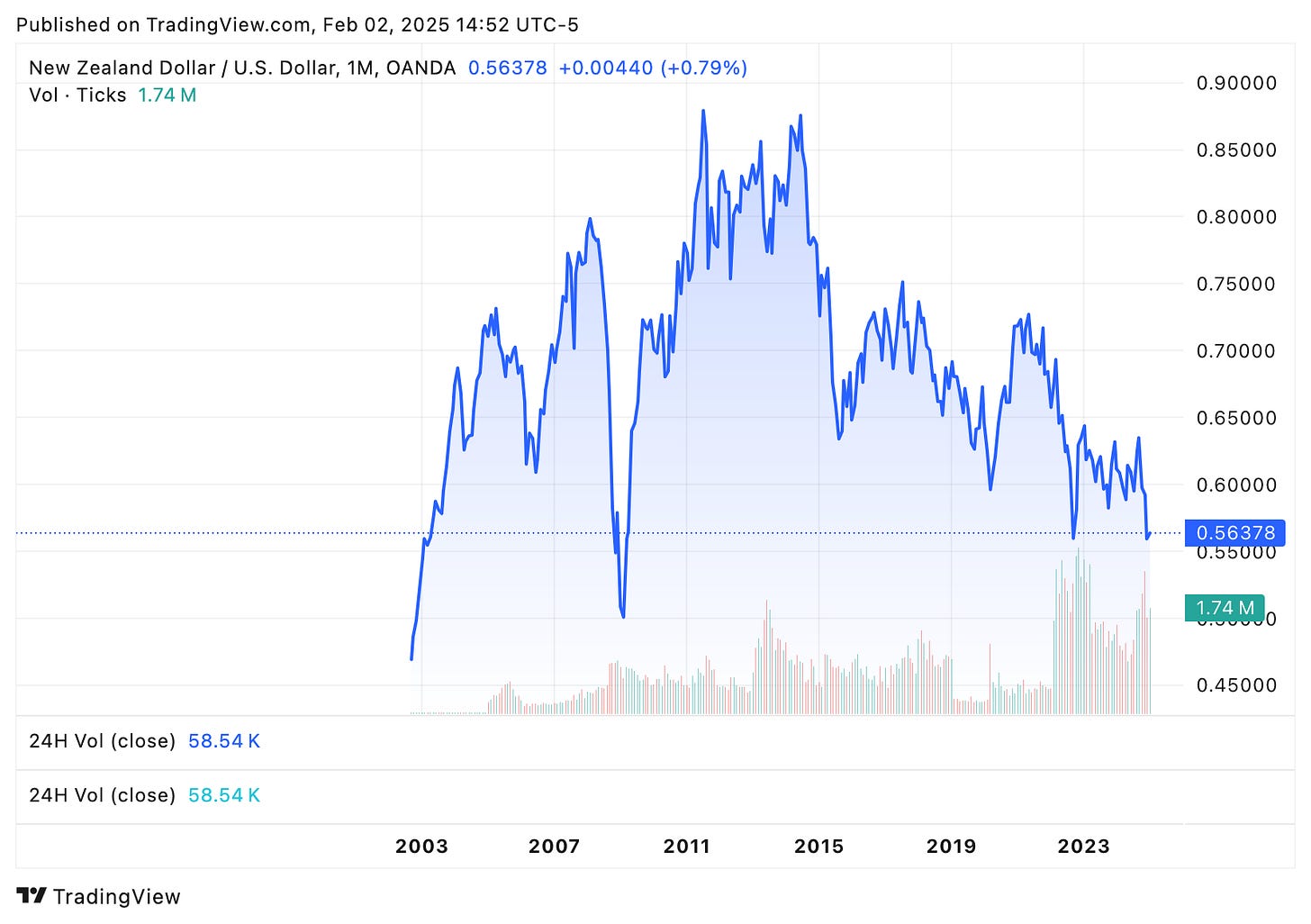

Financial markets have already reacted badly, pushing the NZ dollar down almost 1% this morning to near a post-covid low of 55.8 USc. That weakness will on its own generate inflation for New Zealand consumers.

Global stagflation adds new headwind to NZ’s recession-hit economy

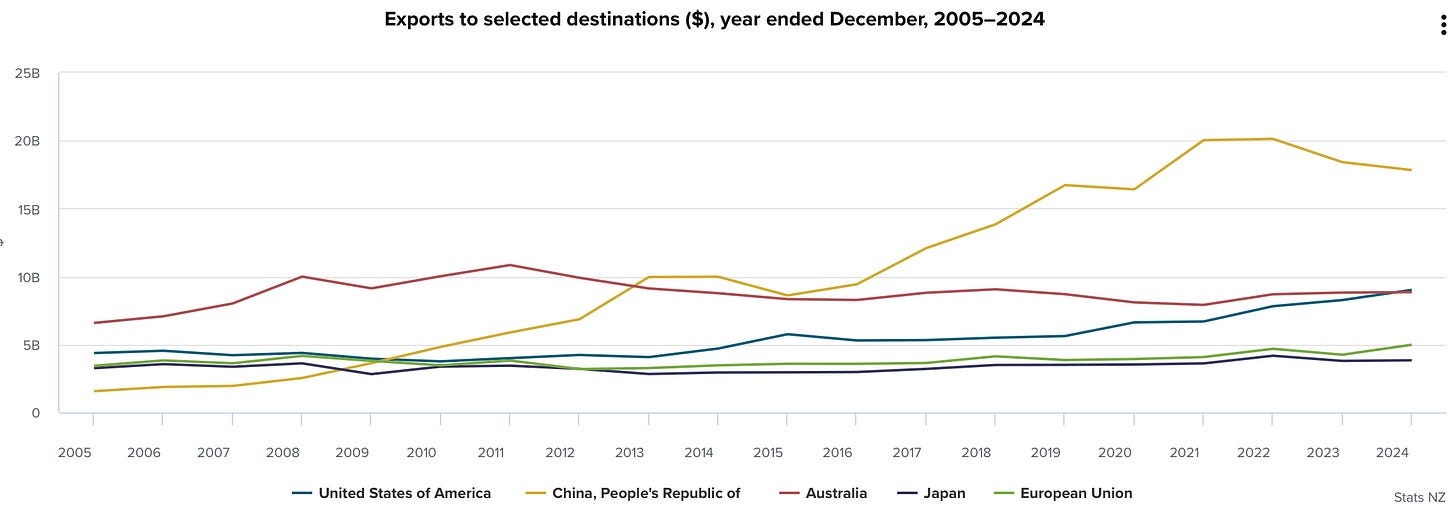

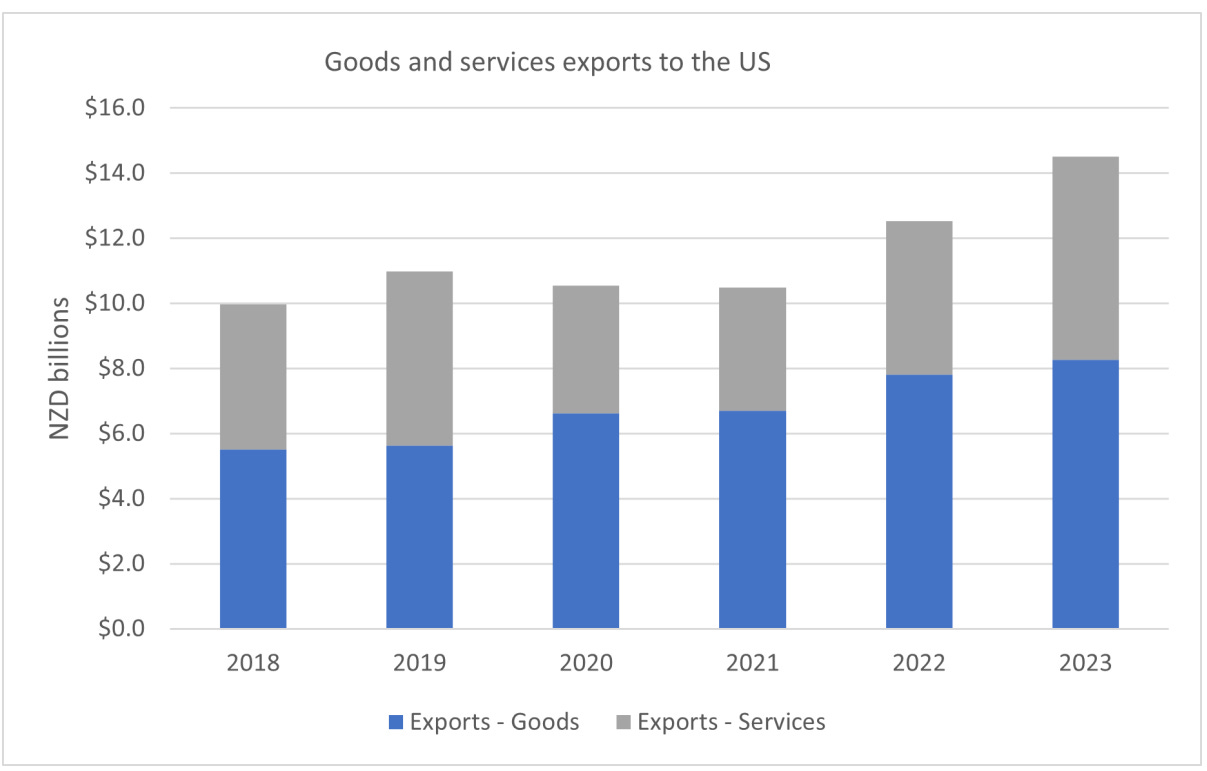

Over the last two years, New Zealand’s economy has been the exception in a world of solid-to-strong economic growth, powered by looser fiscal policies and lower interest rates in other countries. That helped soften the blow of very tight fiscal and monetary policy here over the last two years, with our terms of trade improving and exports to the United States in particular doing well.

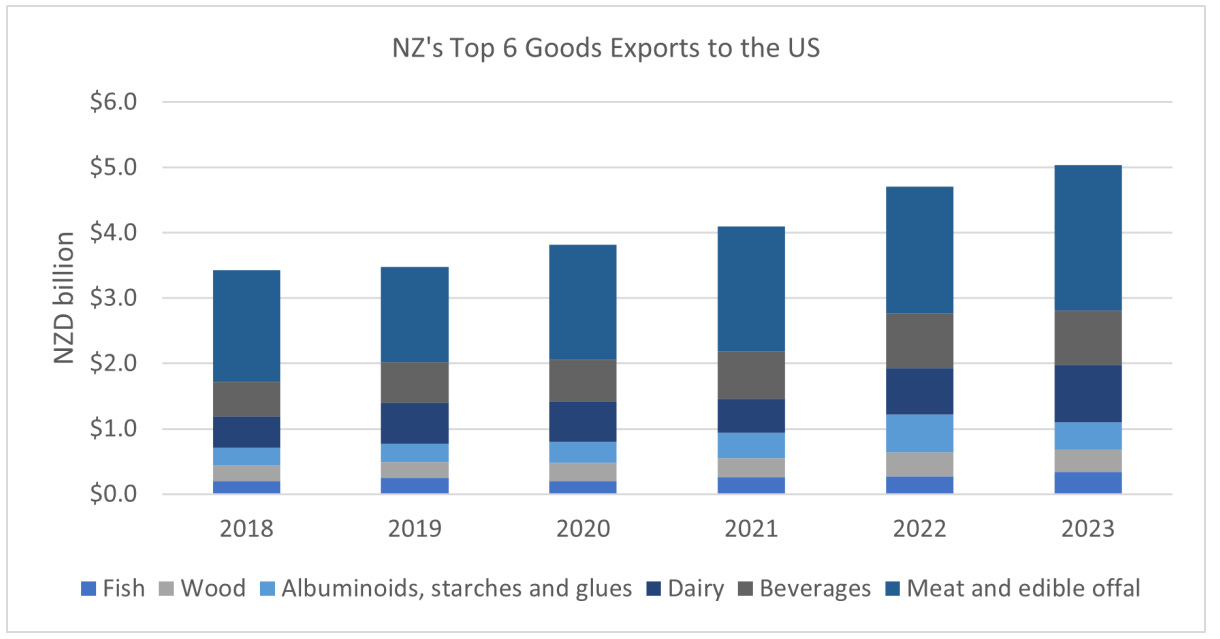

The United States is now our second largest trading partner after China and ahead of Australia, powered by growth in meat and wine exports, along with US tourism recovering to pre-covid levels while Chinese and Australian tourism haven’t.

New Zealand is now the third largest provider of wine imports to the United States and the fifth largest exporter of beef to the United States, after Canada, Australia, Brazil and Mexico.

NZ exports more wine to the US than Australia

NZ beef export values strong, even if volumes are capped by tariffs

The effects on our exports to the United States of the 25% tariffs on imports of beef from Mexico and Canada are unclear, given Australia has a free trade agreement with the United States and our beef exports already face a 26.4% tariff on exports above 213,402 tonnes per year, which we’re now regularly hitting. Australia stands to gain the most, given it already has a free trade agreement and we don’t.

US inflation and interest rates crucial to mortgage rates here

A major swing factor in how the new tariffs change our political economy will be how US longer term bond yields move, given they form part of the base for our fixed mortgage rates. Higher US inflation is likely to drive up US interest rates and starve borrowers here of the big rate cuts they, and the Government, may have expected.

Chart of the day

Cartoon of the day

Timeline-cleansing nature pic of the day

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Although Australia’s free trade agreement with the United States puts it in pole position to win market share in beef at the expense of Mexico, Canada and New Zealand, given New Zealand still faces tariffs.

Share this post