Long stories short, the top six things in our political economy around housing, climate and poverty this week were:

PM Christopher Luxon and Transport Minister Chris Bishop announced the immediate reversal of the previous Labour Government’s 100 km/hr to 80 km/hr speed limit reductions on 38 sections of state highway, saying it would save around 3 minutes per trip on average;

Luxon trumpeted the news as another sign the Government was speeding up the economy, saying “we're really pleased that we are literally literally accelerating New Zealand's economic growth with this announcement today.”;

However, an analysis via Stuff showed the main 11km-long road section in question between Carterton and Masterton would save a motorist 90 seconds if they were able to drive 100 km/hr vs 80 km/hr, and transport economics experts such as Simon Kingham and the PHCC have challenged the assumed economic benefits of faster trips, saying most workers use the time saved at home, rather than at work;

The Government’s talk of economic benefits also ignored the extra health, fuel and carbon emissions costs of faster driving, more accidents and more lethal accidents, with a 2023 analysis by EY of speed limit reductions for the Napier-Taupo highway, for example, showing a net benefit of $92.6 million a year, after reduced accident costs and lower fuel costs of $94 million overwhelmed the $1.3 million of benefits from time saved;

Meanwhile, the Reserve Bank’s Chief Economist Paul Conway delivered a quietly devastating speech on Wednesday that showed New Zealand’s low-investment, low-wage, migration-led and housing-market-driven political economy had delivered poorer productivity growth than the rest of the OECD and meant total economic growth in the last decade in particular had come from more people working longer hours, rather than investing and training to get more from each hour of work.

New Health Minister Simeon Brown announced on Friday a new hospital would be built in Dunedin with fewer beds than the current one, which nurses, doctors and other locals in the South Island meant the Government was repeating the mistakes of predecessors of encouraging population growth without building the infrastructure before people arrive.

(There is more detail, analysis and links to documents below the paywall fold and in the Saturday soliloquy podcast above for paying subscribers. If we get over 100 likes from paying subscribers we’ll open it up for public reading, listening and sharing.)

Luxon ‘going for growth’ by encouraging faster driving

PM Christopher Luxon and Transport Minister Chris Bishop launched the start of reversing speed limit reductions brought in last year by the Labour Government, arguing it would improve economic growth. But they gave no evidence to show that. Cost benefit analyses done on the lower speed limits show repeatedly that the extra benefits of saved time are overwhelmed by the extra costs of more accidents and more lethal accidents.

‘More people driving faster & working longer hasn’t worked’

Reserve Bank Chief Economist Paul Conway gave an important speech on Wednesday that effectively called bullshit on Aotearoa’s economic modus operandi for the last 30 years of buying a larger economy through population growth from migration and a higher portion of the population working more, and for longer hours.

He detailed how our economy had appeared to outperform our peers because the simple GDP growth rate had been higher than others, but that disguised an increasingly poor productivity growth record which meant output-per-hour worked has lagged. I’ve included the video of the speech below and reproduced the key charts, along with the key quotes from the speech.

In summary, Conway argued:

Unlocking higher investment and productivity growth is key to raising potential output growth and improving per capita incomes. This would also reduce the likelihood of negative recessionary economic growth during future periods of restrictive monetary policy. RBNZ Chief Economist Paul Conway in a speech

This takes us back to the same old problem. New Zealand households put their savings into leveraged residential land because the after-tax, after-leverage and risk-adjusted returns are vastly higher than any other investment in real businesses, infrastructure and skills development. That’s because, unlike other countries, we don’t tax capital gains, don’t have an inheritance tax and don’t incentivise savings in pension funds.

It means that our political economy is frozen in the headlights of an endlessly unresolved debate about taxing capital gains. The current Government has rejected reform to taxes on capital gains and current Labour Leader Chris Hipkins appears increasingly reluctant to talk about the issue, having already once baulked at campaigning on it as leader.

Conway did not address capital taxation in the speech, but the detail on the failure of the economy to grow productivity faster because of the lack of investment was quietly devastating to the current approach.

The current model wasn’t working, he made clear (bolding mine):

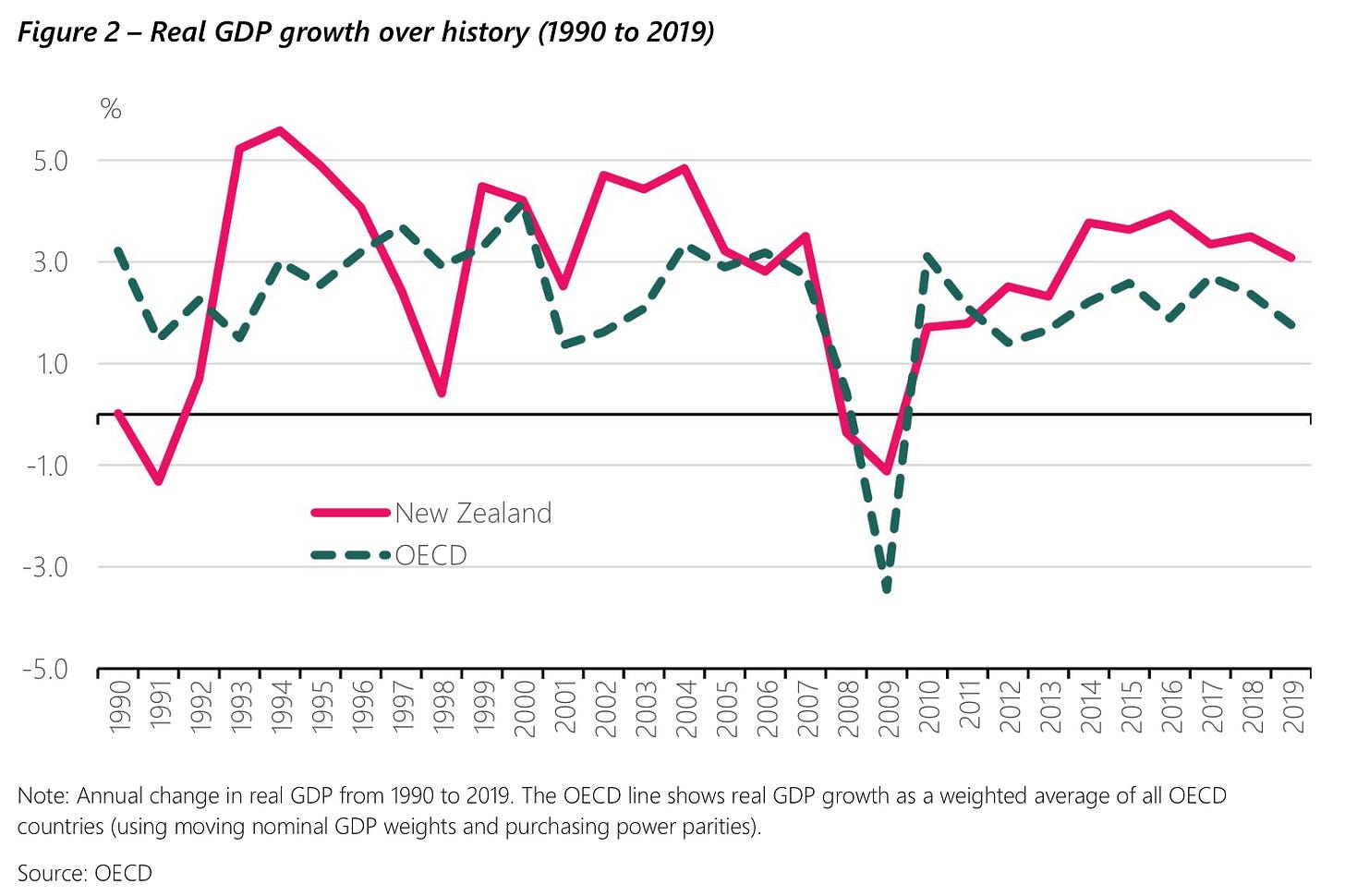

Over recent decades, up until COVID-19, annual GDP growth in New Zealand has often been above the OECD average, indicating relatively rapid potential output growth.

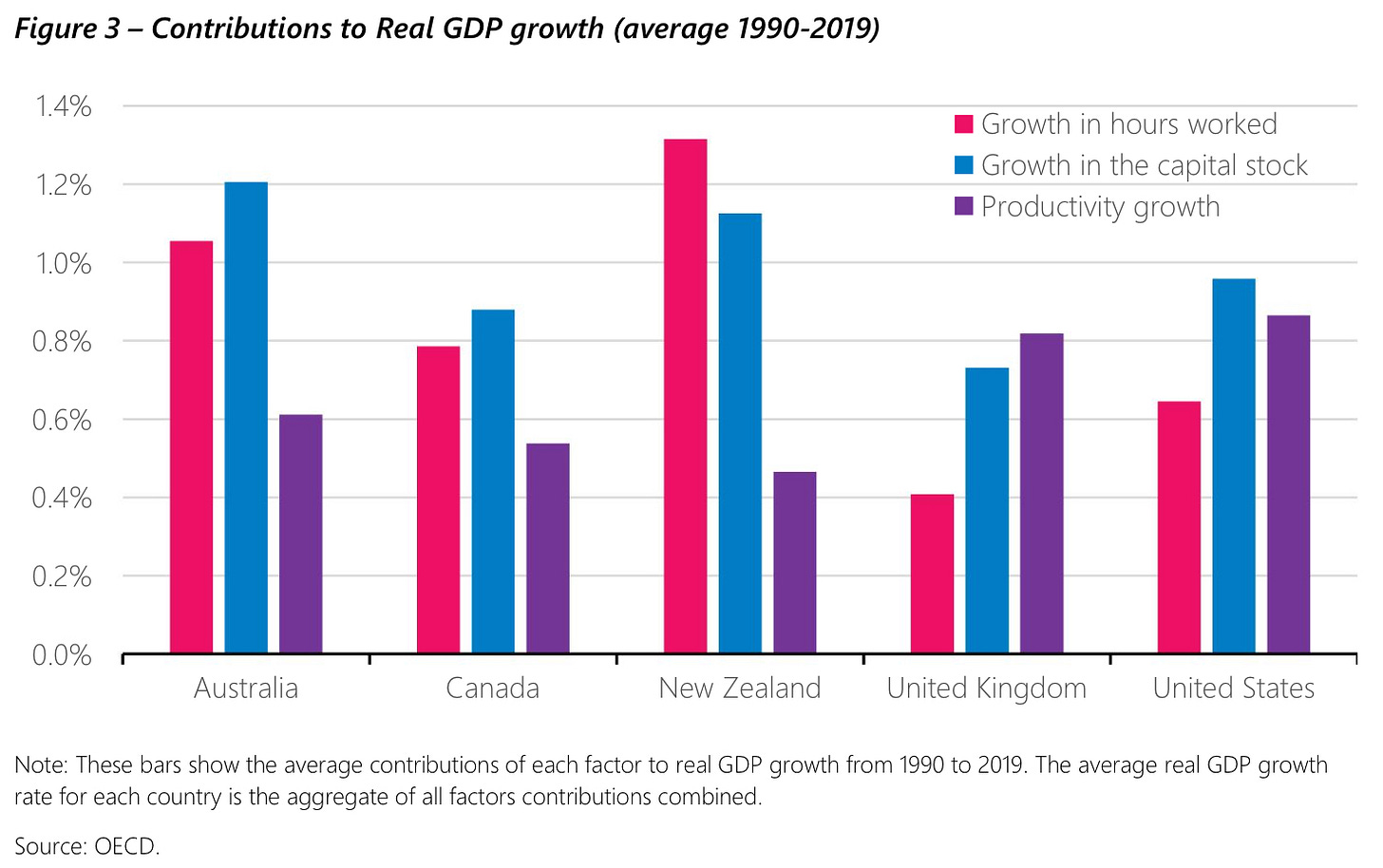

A closer look reveals that compared to other countries, potential output growth in New Zealand has been driven more by increases in labour input, rather than by productivity improvements. Growth in the capital stock has also contributed to potential output growth, although the amount of capital available per worker in New Zealand is low in comparison to other developed economies.

Strong growth in labour input over recent decades reflects generally strong inward migration flows, in addition to increased participation in the labour market by New Zealanders. So, while growth in GDP and potential output has been above the OECD average, increased output has been spread across a fast-growing population working relatively longer hours per capita.

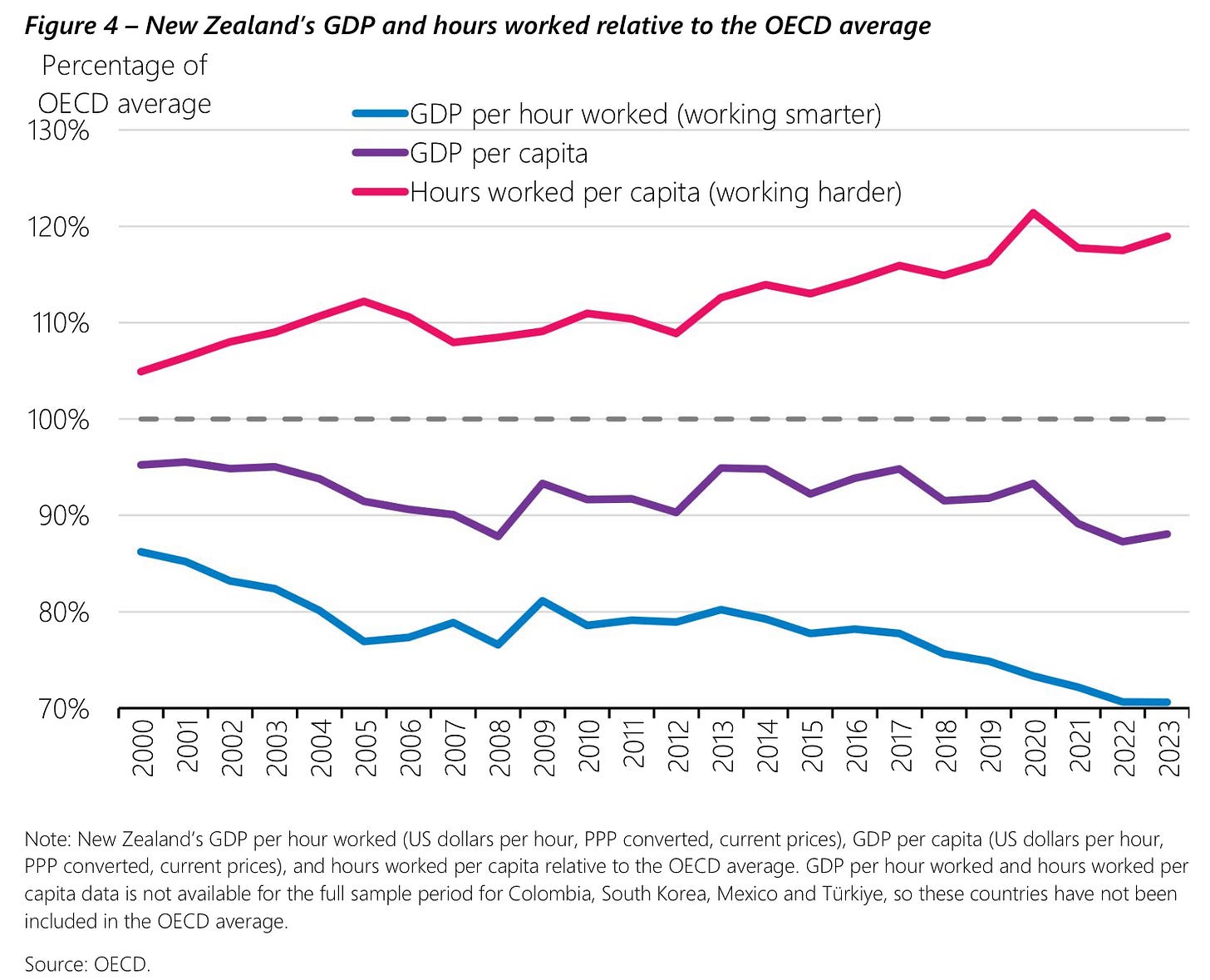

This ‘labour-intensive’ approach to growth can be seen in cross-country comparisons of GDP per capita. In short, there are two ways to increase GDP per capita: by working more hours per person (working harder) or by increasing output per hour worked (working smarter).

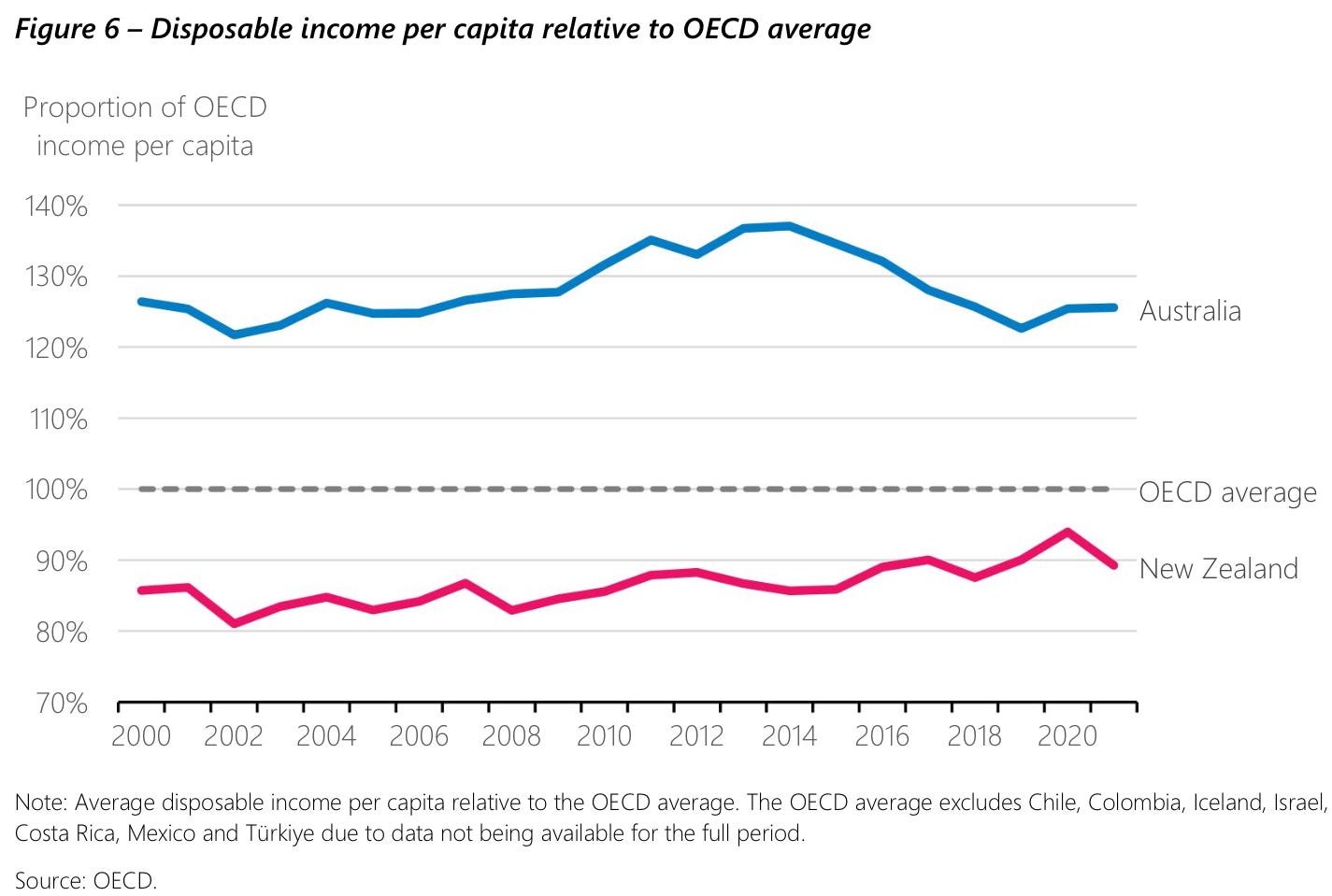

Since the early 2000s, GDP per capita in New Zealand has fallen from around 95% to just under 90% of the OECD average (Figure 4). This relative decline reflects declining labour productivity relative to the OECD average. Hours worked per capita has increased, but not by enough to offset declining productivity vis-à-vis the OECD average. New Zealanders now work almost 20% more hours per person but produce around 25% less output per hour compared to the OECD average. Paul Conway speech

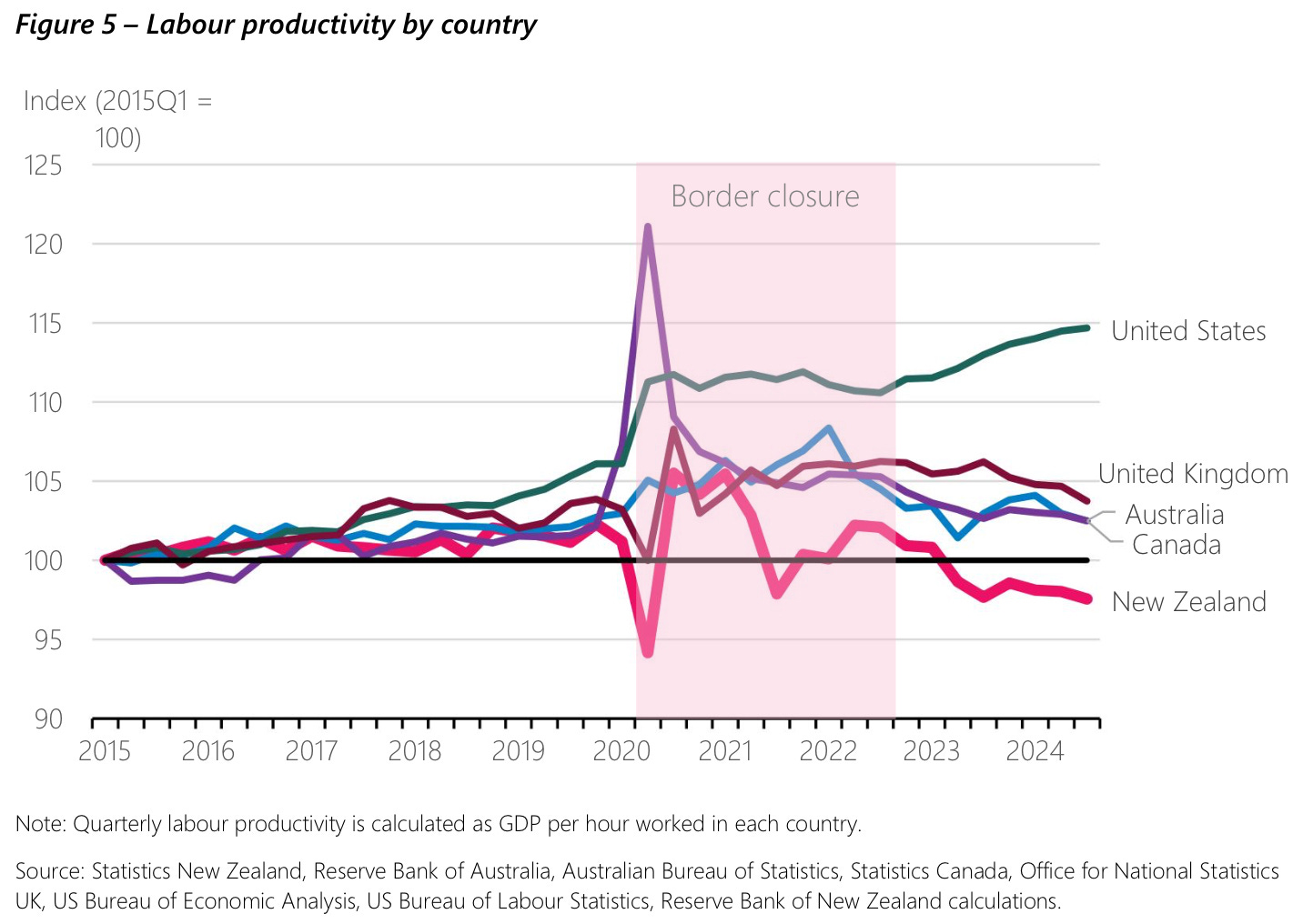

New Zealand’s performance since Covid was particularly poor, Conway noted.

He also pointed out New Zealand household disposable income underperformance relative to our peers would have been even worse, had it not been for an historic improvement in our terms of trade (ie our export prices rose faster than import prices) and low depreciation because of our capital shallow economy. He said this had lowered the expected growth rate in the years to come.

Here’s the core of the speech (bolding mine):

Over the next three years, we currently expect potential output growth to range between 1.5% and 2% per year. This is a lower economic ‘speed limit’ than in the recent past. This subdued outlook stems from expected ongoing weakness in productivity growth and lower net immigration.

Notably, New Zealand’s productivity is now well below the OECD average and that of more advanced economies. This ‘productivity gap’ implies significant opportunity for New Zealand businesses to adopt existing technology and to ‘catch up’ to the productivity levels of businesses in leading economies.

Of course, that is more easily said than done. Reforms aimed at improving New Zealand’s productivity performance would have to mitigate some deeply entrenched structural issues that have held back productivity growth.

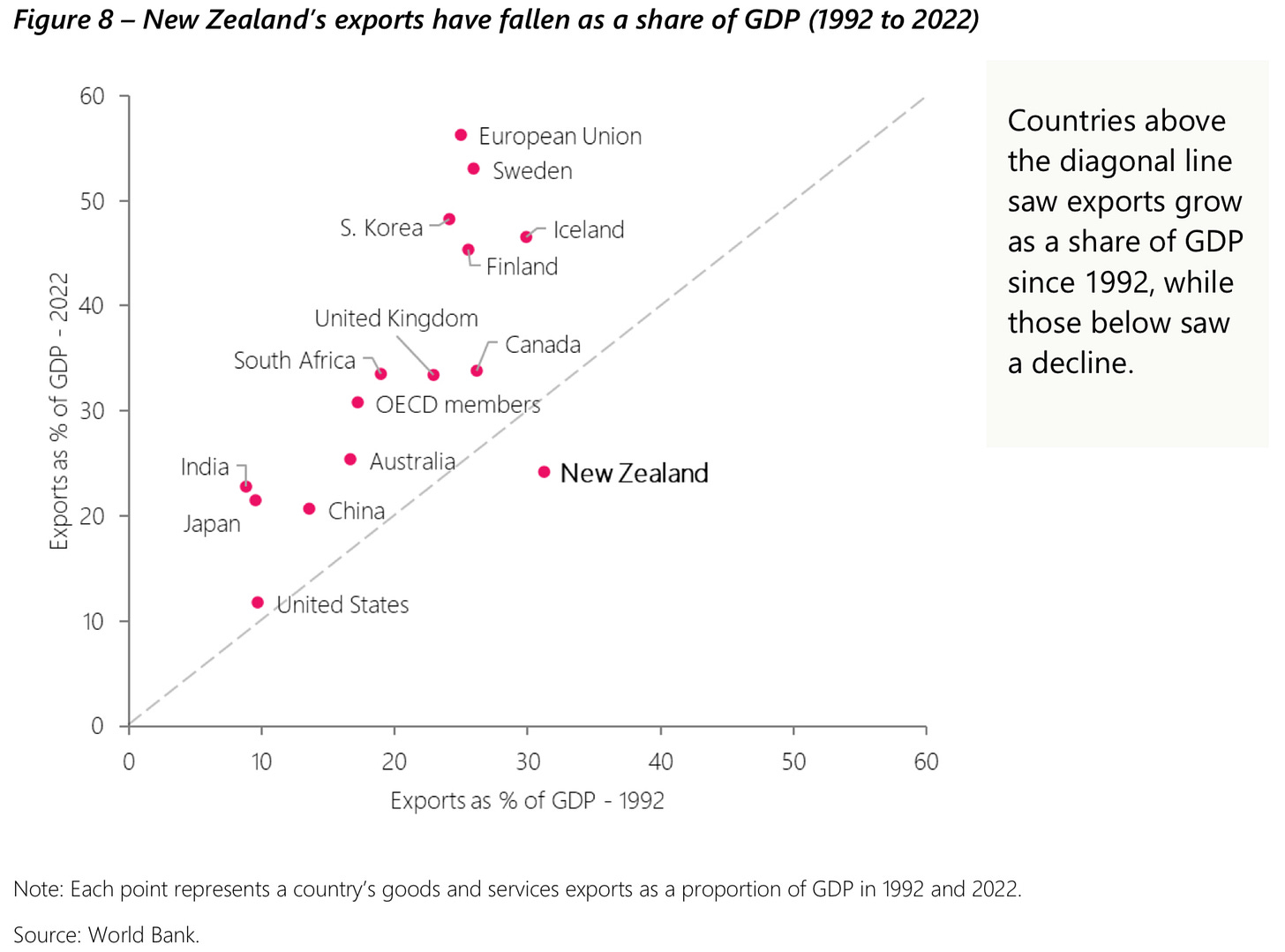

First, for a small economy, New Zealand is poorly connected internationally. For example, our export intensity is among the lowest across small economies and has weakened further in recent years. Foreign direct investment into the economy is also typically below the OECD average as a share of GDP. Paul Conway in a speech

Conway emphasised how the economy was ‘capital shallow’:

This ‘international disconnect’ limits the diffusion of new technologies into the country. Combined with small and insular domestic markets, it also limits scale, competition, innovation, and the efficient allocation of resources, all of which are fundamental to improving productivity.

Second, the flip side of our economy being labour-intensive is that it is capital shallow. While non-residential business investment as a share of GDP has only been slightly below the OECD average, it has been thinly spread across a rapidly growing workforce.

Financial flows into owner-occupied housing have been prioritised over investing in productive businesses. There has also been an emphasis on paying dividends, rather than on fostering growth, with high dividend flows offshore given extensive foreign ownership in core sectors.

The New Zealand equity market is also very small relative to the size of the economy and many significant New Zealand businesses are structured as co-ops or partially government owned, all of which makes third-party investment challenging.

Third, investment in ‘knowledge-based capital’ also appears to be relatively weak across New Zealand businesses. Improving productivity requires investment in R&D, education and skills, organisational know-how, and managerial capability. These are all areas where New Zealand tends to lag. Paul Conway in a speech.

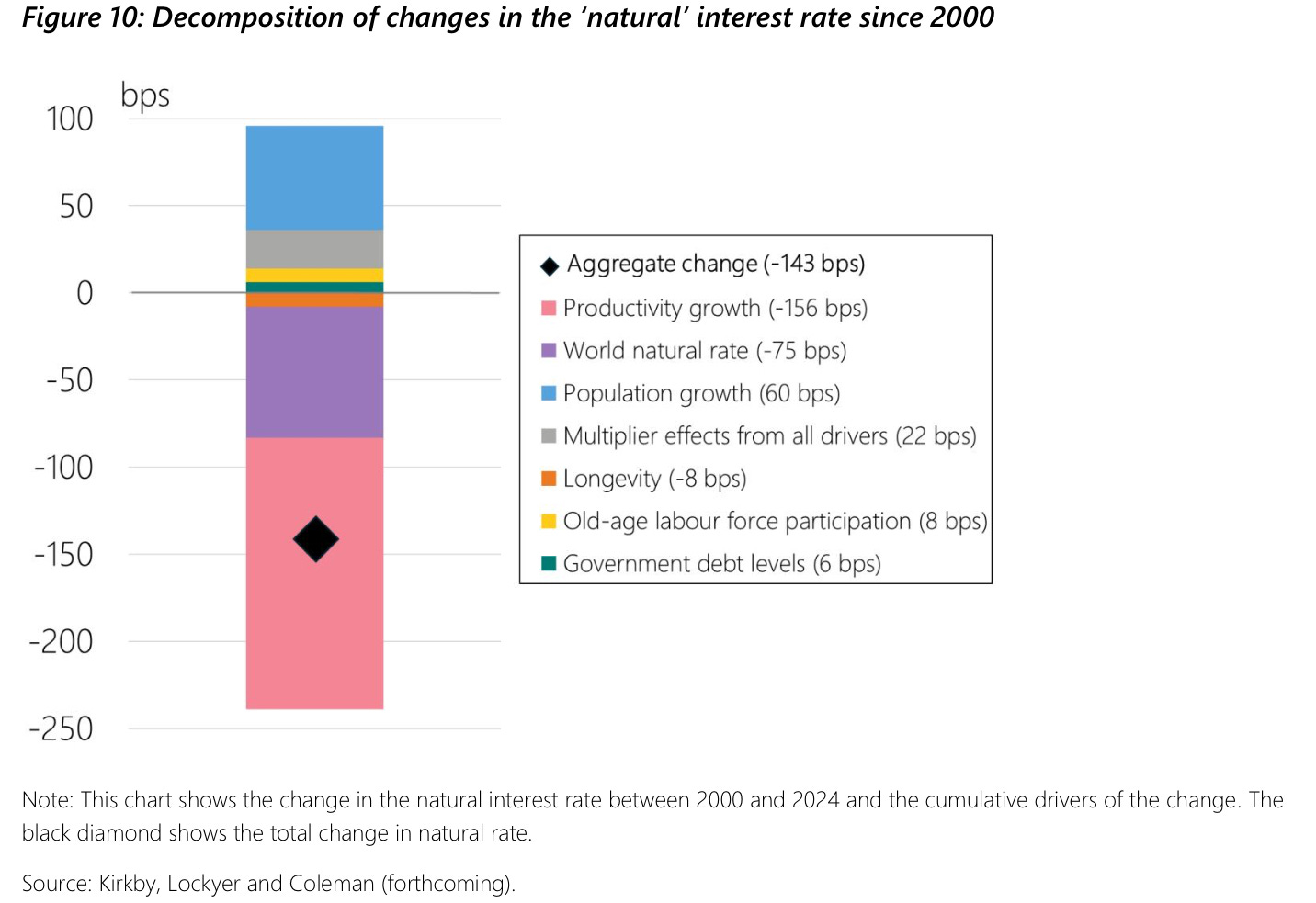

The final section of his speech talked about how the ‘natural’ or neutral interest rate for the economy had risen since Covid, but his discussion explaining the fall in neutral rates from 2000 to 2020 showed just how important population growth was and how little effect Government debt had.

Have a great weekend.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Share this post