Kia ora.

Last month I proposed restarting The Kākā Project work done before the 2023 election as The Kākā Project of 2026 for 2050 (TKP 26/50), aiming to be up and running before the 2025 Local Government elections, and then in a finalised form by the 2026 General Elections.

A couple of weeks ago I asked the first of TKP 26/50’s six fundamental questions:

What population growth rate do we want on average over the next 25 years? Here’s the article, which has an amazing comment stream beneath it. The answers to the poll were broadly split between population growth rates of 0.5, 1.0% and 1.5%. No growth was the least popular option.

Now it’s time to ask the second question:

What specific improvements in Aotearoa do we want by 2050?

I wrote in the introductory TKP 26/50 post that I believed we should aim for:

homes costing no more than 30% of average equivalised household disposable income to live in by 2050, regardless of whether they’re owned or rented;

Climate emissions of net zero by 2050; and,

No one reporting any of the severe material hardship measures, as specified in the Child Poverty Reduction Act.1

We are a long, long way from all of those things now.

Stats NZ’s most recent household income and housing cost figures for the year to the end of June, 2023 showed:

The average cost of housing is more than 40% of disposable income for 18.2% of all households (up 2.9 percentage points from a year ago);

including 27.5% of households that did not own their dwelling (up 3.4 percentage points); and,

13.3% of households that owned or partly-owned their dwelling (including dwellings held in a family trust) (up 2.6 percentage points).

Just to be clear, average annual equivalised disposable income (after tax and transfer payments) increased from $53,192 to $56,919 (up 7.0 percent) in the year to the end of June 2023.

There are 617,400 households or 31.4% of all households paying more than 30% of average disposable income, including:

316,500 households or 24.8% of all homeowning households pay more than 30% of income for housing; and,

299,900 or 44.5% of all renting households pay more than 30% of disposable income in rent.

Our gargantuan housing affordability problem needs a massive response

Aotearoa has the highest proportion of highly stressed renters in the world. The affordability of home buying relative to pure incomes has improved in the last couple of years because prices fell at the same time as incomes rising faster than normal in nominal terms. But that affordability improvement has evaporated in the ways that matter because interest rates are higher and deposit requirements for first home buyers remain tough.

There are all sorts of ways to measure housing affordability, including:

house price to income multiples, which are useful for home buyers, but don’t take into account changes in mortgage rates or deposit requirements, and also ignore the affordability of renting;

weeks or years required for a couple earning a median household income to save the deposit to buy a first home, which also doesn’t take into account changes in mortgage rates or deposit requirements;

rental affordability, expressed as rents as a share of equivalised disposable household income, and in particular the median rental shares;

rental stress thresholds, expressed as the number or share of rental households paying more than 30% or 40% of equivalised disposable income; and,

the number of households on the social housing register.

My preference is for a measure of the number of households having to pay housing costs of more than 30% of average household equivalised disposable income, with the aim of reducing that to zero by 2050. That threshold is the broadly accepted one to indicate anything above that is creating stress.

Using the metric of housing costs including either rent or ownership means that renters are taken account of, along with the ‘other’ costs of home ownership besides the mortgage, including insurance, rates and maintenance.

Currently, there are at least 617,400 households in the position of having unaffordable housing, including 316,500 homeowning households and 299,900 renting households. Broadly speaking, around a quarter of homeowners are in housing stress and nearly half of renters.

That is an awful indictment of our country. Solving it solves so many other problems.

Our climate actions are lax at best and dangerously deficient at worst

Currently, Aotearoa is barely on track to meet its emissions reductions budgets to achieve net zero by 2050, as legislated, but only because Governments of both flavours have relied heavily on pine planting to suck up carbon in the short term to achieve the ‘net’ part of the target. This strategy doesn’t solve the problem of how to cut gross emissions and climate warming in the short term, which is needed to avoid dangerous warming beyond 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. Planting pine is a ‘once-only’ thing, given land can only be planted once, and is vulnerable to being knocked over in storms and burnt in fires that are more likely as the planet warms.

The other ‘official’ target Aotearoa has is the much tougher Paris target for 2030, which we are currently set to miss by a long way without buying emissions credits overseas, even though the emissions credits markets don’t exist and aren’t recognised internationally. And there are less than six years to go before 2030. We have signed trade agreements assuming we will reach those.

The Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) New Zealand agreed to in updated form from 2021 was to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, which implies we will produce a total of 571 Mt CO2e of emissions over 2021 – 2030. We are currently on track to produce 100 Mt more than that Budget by 2030.

In the first post, I wrote Aotearoa should at least aim to reach net zero for climate emissions by 2050, as legislated for currently, and also achieve our Paris targets for gross emissions reductions without the need to buy international credits. As He Pou a Rangi-The Climate Commission has argued, we should not be using pine plantations to ‘save our skin’ in climate accounting terms. Pine planting is a crutch stopping us from doing what is necessary: reducing gross emissions.

We should be planting (native and other carbon-hungry species) with our ears pinned back anyway because it will help suck carbon out of the air right now, which is what’s needed urgently to try to take even a tenth of a degree off the rise in global temperatures. But I think that planting has to be done consciously for land use change reasons, which all at once reduce methane emissions, stabilise landscapes, increase bio-diversity and create great new places for us all to enjoy life in. Simply planting pine for climate accounting and ETS cash reasons is pointless and reckless, given the risk of storm damage, fire damage and the risks of more Cyclone Gabrielle-style slash disasters.

In my view, we should achieve the Paris agreement target by 2030 and reduce transport, housing and electricity emissions to as close to zero by 2050, with forest planting and the associated land-use change doing the work of cutting agricultural methane emissions by 10% by 2030 and 24-47% by 2050, as legislated for in the Carbon Zero Act.

Our poverty reduction aims aren’t ambitious enough, or even being met

I wrote in the first TKP 26/50 post I think we should aim to for no-one being in a position to say in the Stats NZ Household Income survey they don’t have enough income for rent, food and electricity, and that no one is in a position to say in the survey their house has a major mould problem, or is a major problem to heat.

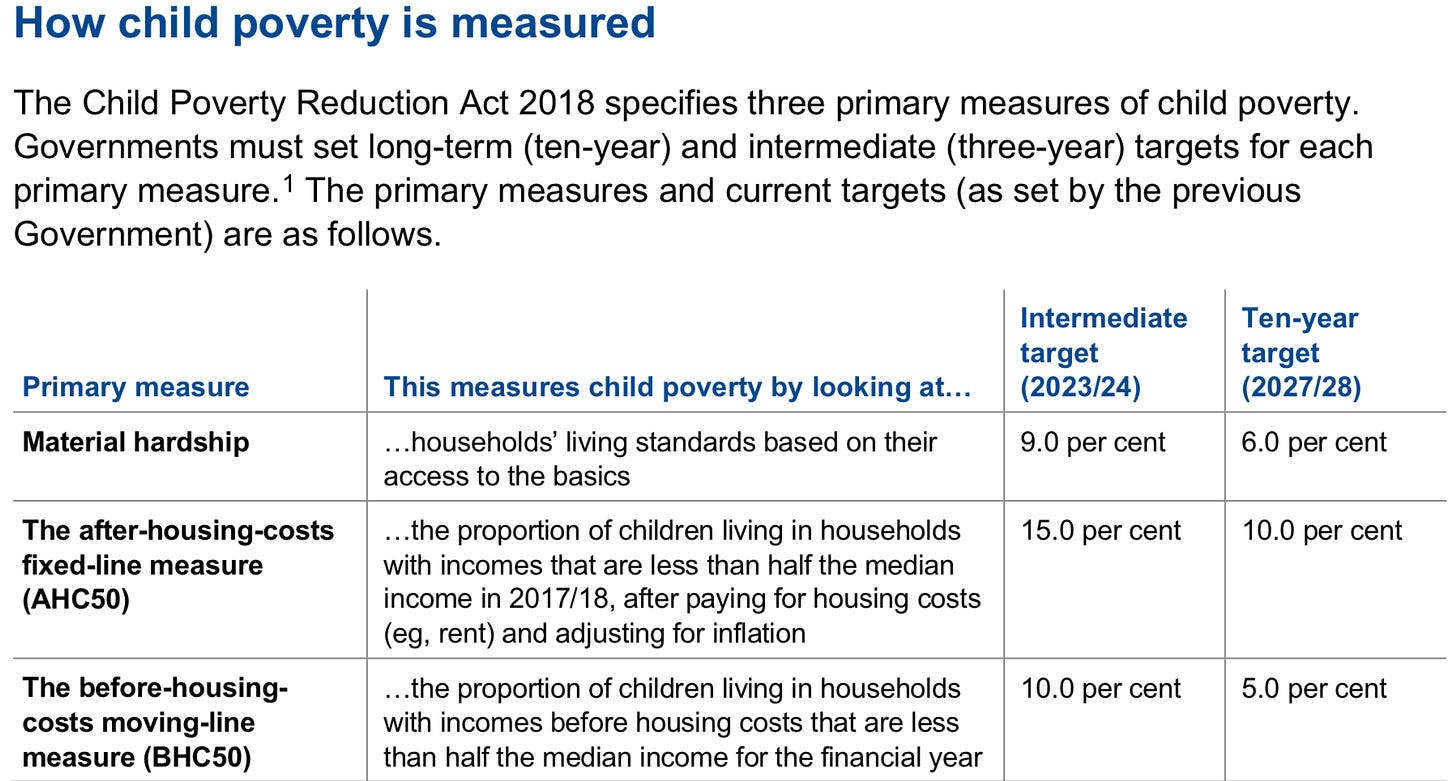

The Child Poverty Reduction Act of 2018 specifies the Government must aim to reduce various child poverty measures, but allows the flexibility to change the end-points. Here’s what the previous Labour Government aimed for:

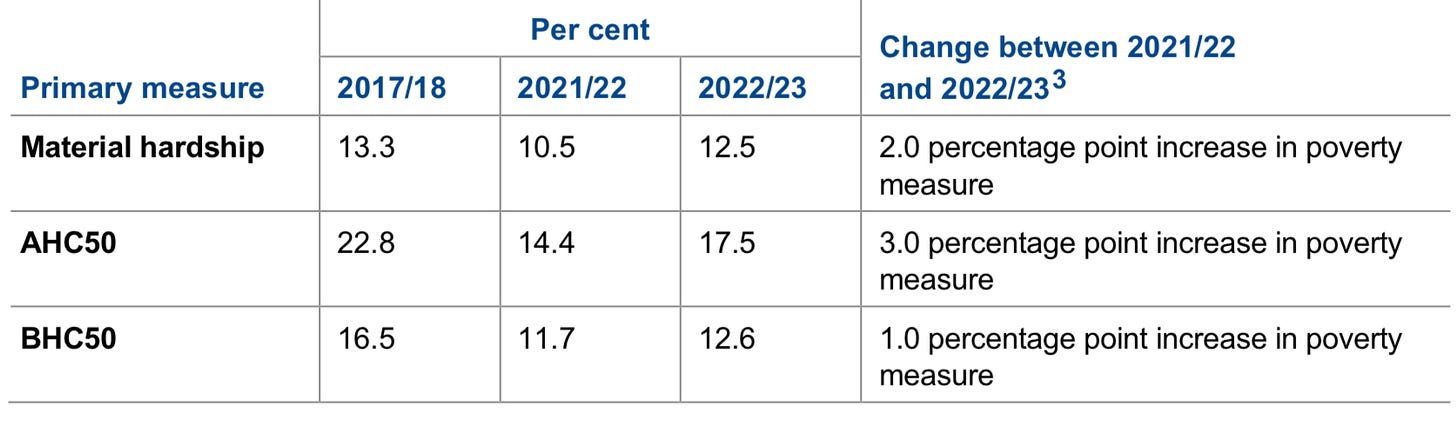

Here’s how it went until the end of June, 2023 at least:

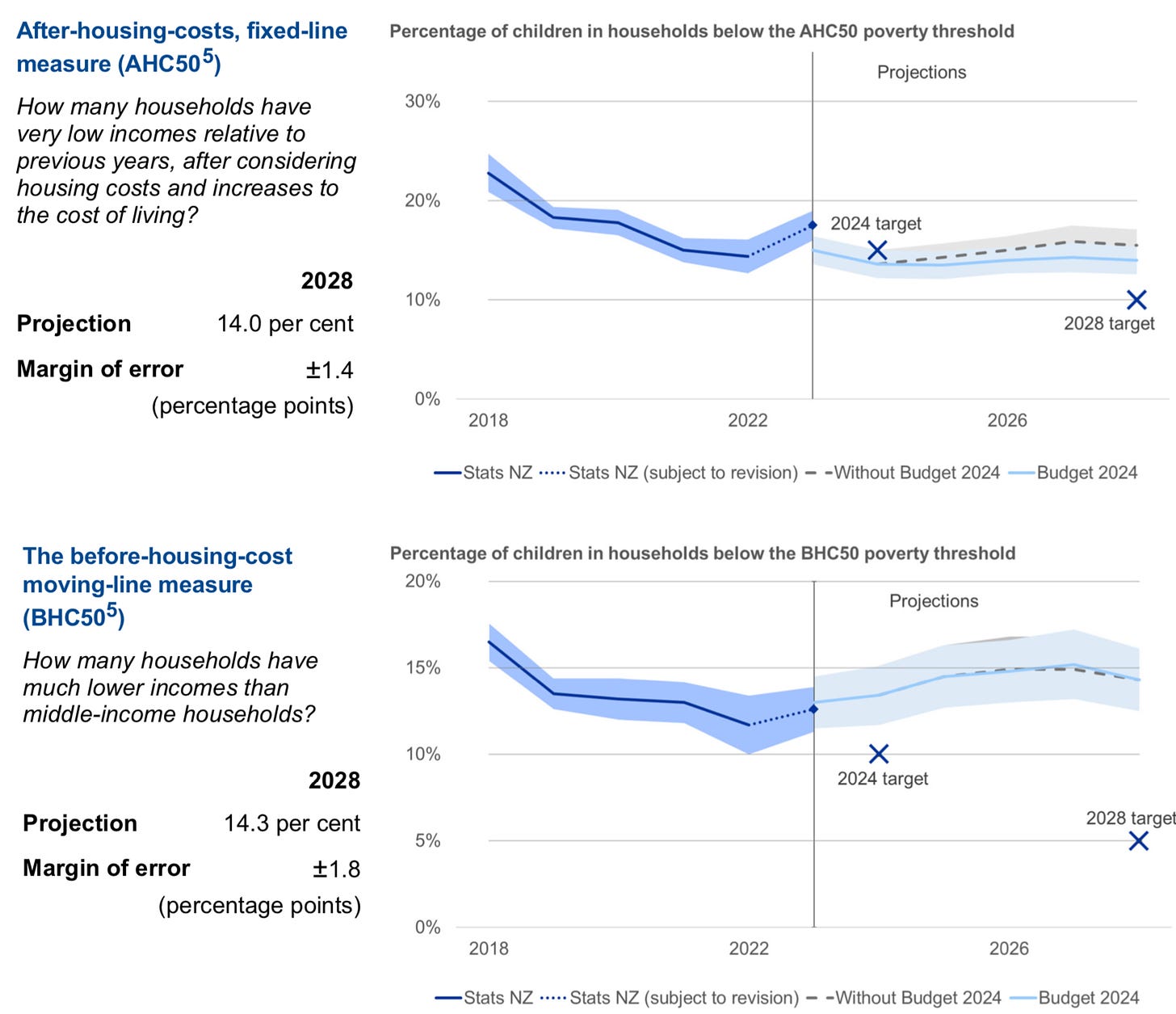

Here’s what Treasury forecast:

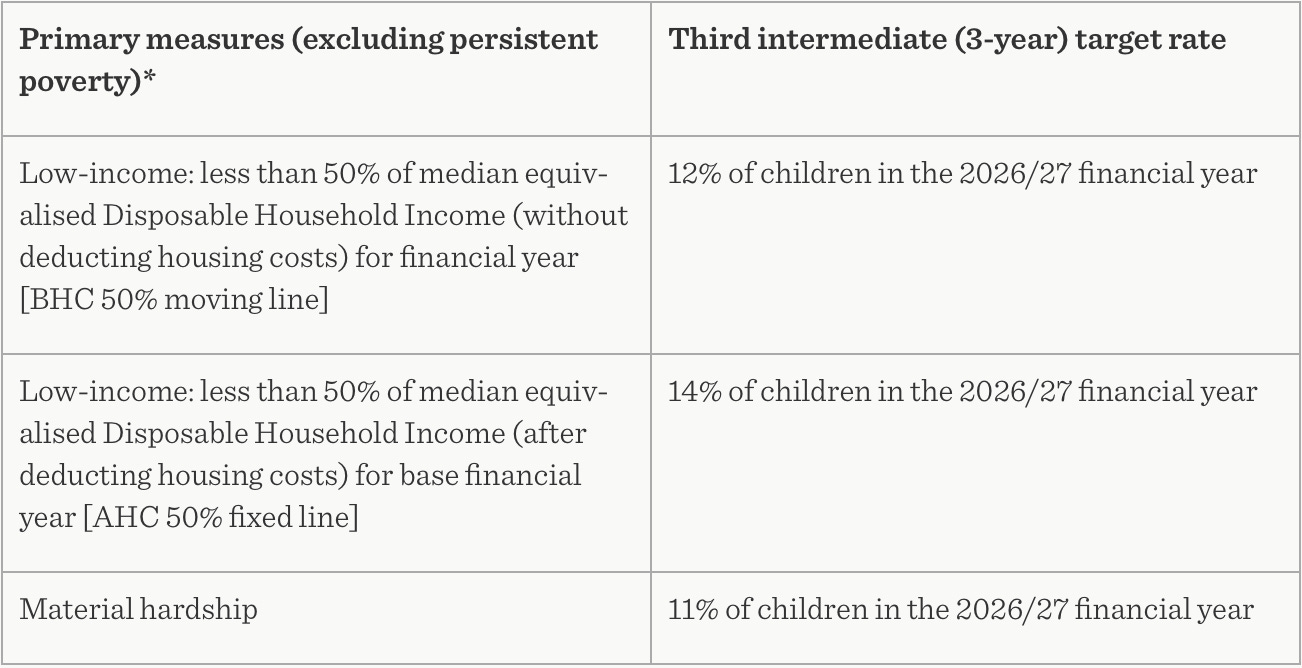

Then, just quietly, the new Government moved the goalpost in a way that would see an extra 17,000 living in poverty, as Stuff’s Jenna Lynch reported in late July.

Under the Child Poverty Reduction Act, introduced by the Labour Government in 2018, the Government is required to set medium- and long-term targets for reducing child poverty against three measures.

The Government set new targets through a Gazette notice on June 27 for each of the measures, and two of the three are less ambitious than the previous set of goals. There was no accompanying announcement or press release as has occurred in the past. Stuff

Here’s the new targets:

So the material hardship target was lifted from 6% for the 2027/28 year under Labour to 12% under National.

In my view, the target should be 0% in material hardship by 2050.

A poll to get us started

As in the first post in the TKP 26/50 series, I’ve tried to frame up the question with a series of answers to the question in a poll. In essence, they are designed to be consistent with a status quo-ish fast-GDP growth option, two aggressive action options not necessarily linked to GDP growth, and a de-growth option.

There’s limited space for descriptions in the options, but Net 0 means Net Zero emissions, Gross 0 means Gross Zero emissions and 0 MH means zero people living in severe Material Hardship.2

That’s it for now. I’ll be releasing the final four questions in the coming days.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Share this post