Kia ora.

The Sunday before last I proposed restarting The Kākā Project work done before the 2023 election as The Kākā Project of 2026 for 2050 (TKP 26/50), aiming to be up and running before the 2025 Local Government elections, and then in a finalised form by the 2026 General Elections. That would give us time during 2024 to:

Ask six fundamental questions about what Aotearoa wants and how to get there;

Discuss those questions and possible solutions with a range of people in a series of interviews and special ‘Hoons’;

Run a series of surveys and polls of readers and subscribers to understand a wider view on the answers to these questions;

Propose a draft set of options as a base for refining and testing them; and,

Gather and crystallise those views into a more refined set of policies by the end of 2024.

Then through 2025 we would:

continue thrashing out and tempering those aims, assumptions and solutions through the process of covering the 2025 Local Government elections; and,

finalising a set of coherent policies in an edited book and/or section of The Kākā that would be refined and finalised by the end of 2025.

Then during 2026, we would:

launch a section of this website and/or book for free to a wider public for discussion through public webinars, online surveys, articles and podcasts from early 2026, up to and including the general election of late 2026;

the website or book would be called The Kākā Project of 2026 for 2050 (TKP 26/50) and include an edited summation of our exploration, the views of the people and subscribers we talked with, and the settled set of policies, as of the end of 2025; and,

I would interview as many party leaders and politicians through 2026 and cover their election positions and policies in relation to the policies outlined in (TKP 26/50)

It was one of our most popular posts in nearly four years of publishing. The overwhelming feedback was to go ahead with the plan, including dialing back on some of the news curation work I’ve been doing and thinking a bit longer term about solutions, rather than just the current problems.

Aotearoa’s problems and opportunities

Regular readers and listeners will be familiar with the problems I see facing Aotearoa in our political economy around unaffordable housing, worsening poverty and climate inaction, and the opportunities for improvement, but if only we could agree on what we want and how to get there. The frustration for many is the lack of a coherent framework to change things in a substantial way that more than 50% of voters could agree on to change our collective ‘operating system’ as a nation. We know we need a ‘reboot’ to:

Make housing affordable to rent and buy again;

Vastly reduce poverty and improve everyone’s health and happiness; and,

Massively reduce climate emissions quickly and future-proof our lives for a much warmer, stormier and unstable planet.

It feels impossible right now, but we have actually done this three times before in the last 130 years or so. In times of crisis, we have used our democratic processes to change the size, structure and way our Government runs the economy and society to solve what we felt were nation-threatening problems. In times of crisis, we have pivoted, changed almost everything and improved things (mostly) for the next two or three decades. We have done it roughly once every 40-50 years since the early 1890s and we’re due another one. My bet is 2026 or 2029 are the potential launching-off points.

So what could or should this next transformation look like? And how could it happen?

Three quick bits of history in reverse

Forty years ago, voters and our political classes from both sides of Parliament decided on a radical period of reform that was to last a decade and flip the political economy from being a state-led, high tax, high public foreign debt, high investment, high(er) equality and more homogenised economy, to one that was low tax, small(er)-state, low investment, high local household debt, vastly unequal, poverty-ridden, much more diverse, less cohesive and divided nation.

Back in mid-1984, nearly two-thirds of voters wanted to change the way the economy and government were run in fundamental ways, albeit they weren’t sure what exactly they wanted or how to achieve it and the vagaries of First Past the Post (FPP) meant 43% was enough for Labour to change everything. Broadly, voters were sick of then-National PM Robert Muldoon1 deciding everything in the economy and society and believed, but didn’t know the full extent, the levels of inflation, economic under-performance, unemployment, foreign debt and stifling controls on everything were unsustainable.

Labour won the July 1984 snap election in a landslide and discovered within two days the country was basically broke and effectively unable to service the Government’s foreign-denominated debts, let alone buy enough imports to continue a modern economy. For two days after the election, New Zealanders couldn’t buy or sell foreign currency after the Reserve Bank shut down the markets to avoid a complete emptying of our foreign reserves and a collapse. The central bank only reopened it when Muldoon was shunted aside by his own caucus and the new Government agreed to devalue the New Zealand dollar by 20%.

Long story short, the Labour and National Governments in power from 1984 to 1993 enacted a series of fundamental changes to how Goverment was run, the size and nature of Government, and how the economy ran. The four centrepiece pieces of legislation underpinning these reforms were the Public Finance Act (1989), the Reserve Bank Act (1989), the Resource Management Act (1991) and the Employment Contracts Act (1991). Despite a few tweaks and failed reform attempts, they (still) are our Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, or our four foundational pillars of prosperity, depending on your point of view2. Listen to Juggernaut for a much more comprehensive and compelling version of this period of radical reform.

Back in late-1935, New Zealand’s economy was wracked by unemployment and despair after the depressions of the 1920s and early 1930s, and after the shock of the Hawkes Bay earthquake of 1931 that destroyed Napier. Some feared wars were coming in Europe and Asia that would drag New Zealand in and it felt as if to-the-death battles were coming between democracies and autocracies, and between capitalism and communism. There had been two weak and divided coalition Governments after the 1928 and 1931 elections that had failed to turn things around after 15 years of being in and out of depression after World War One and the 1918/19 flu pandemic. They were led by the United and Reform parties, which eventually merged to become National.

Labour won the November 1935 election in a landslide and proceeded over the next 10 years to create and/or expand big chunks of the welfare state and publicly funded health and education systems we still largely have. The state grew dramatically and so did income taxes, particularly during World War 2 when the threat of extinction and the need to arm and support ‘our boys’ was paramount. State houses were built in huge numbers relative to the size of the population at the time and our modern electricity, phone and roading networks were filled out. Both National and Labour Governments largely preserved the status quo settled by 1945, at least for the next 40 years, although it was fraying by the early 1980s.

Back in 1891, after more than a decade of depression, a reforming Liberal Government was elected under John Ballance, who was quickly succeeded on his death in 1893 by Dick Seddon, who was PM until his death in 1906. Over a decade of dramatic reforms, the Liberals enacted sweeping changes to land ownership and the way Government was elected and operated. It broke up massive stations owned by a squatocracy into small owner-operated farms from 1893, brought in votes for women in 1893, introduced the Old Age Pension Act in 1898 and introduced the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act in 1894. It was the first state-run system for deciding wages and working conditions that was only really reformed with the passing of the Employment Contracts Act of 1991.

The point of this little economic history tiki tour is to say that Aotearoa’s political economy has gone through periods of massive reform lasting a decade each after an economic crisis and/or nation-threatening event, and that there have been three such episodes, about 40-50 years apart. Each was preceded by periods of intense economic stress and fear of war, and often happened during war or as war was ending.

The period of Liberal reforms from 1893 to 1903 followed a long depression and a period of intense globalisation and industrialisation, along with one overseas war New Zealanders fought in (The Boer War). The 1935 to 1945 era of reform was book-ended by the 1930s Depression and World War Two, both of which provided crises that weren’t wasted. The 1984 to 1993 reforms followed the stagflationary economic shocks of two oil supply crises (1973 after the Yom Kippur War and 1979 after the Iran-Iraq war) and ended as the Cold War was ending with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.

We’re due for a shakeup

I argue the economic and social pressures building in our economy and society feel similar to those generational step-changes, and perhaps not coincidentally, we have just been through the economic and inflationary shocks of Covid and the Ukraine war, which dramatically worsened our existing housing and poverty crises. Some fear we are in a similar leadup to a global conflict between the United States and China/Russia/North Korea that would shut down an era of globalisation. Right now, our Government is edging away from our main trading partner, China, towards joining the American camp.

So what could a program of reform look like if a Government was elected in 2026 to significantly change the nation’s trajectory?

The Kākā Project of 2026 for 2050 (TKP 26/50) is our attempt to come up with better definition of the problems and a coherent set of solutions that have been chewed over in public.

Here’s the first of six questions with options to frame things

The six questions I’d like to pose to subscribers, general readers and interviewees over the rest of the year as the core of TKP 26/50 start with:

1. What population growth rate do we want on average over the next 25 years?

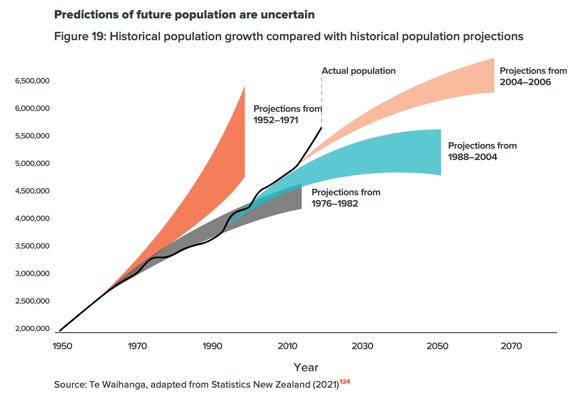

Over the last 20 years, Governments of both flavours projected and assumed population growth of around 0.5%, but delivered average growth through net migration of 1.5% to 2.0% per annum, which deepened our infrastructure deficit to an estimated $100 billion. We continue to project population growth over the next 50 years of around 0.5%, even though we are a climate haven and our current economic structure is pre-set to suck in temporary migrant workers to keep wages and investment low.

This accidentally-on-purpose population-policy-without-debate keeps growing nominal GDP through population growth to achieve budget surpluses and low public debt through GST and income tax growth, without public infrastructure investment to match. It is an essential ingredient behind the current ethos shared by both Labour and National that they can keep the size of Government under 30% of GDP and Government debt under 30% of GDP, without having to change the settings for publicly provided health, education and NZ Superannuation, and without having to tax capital gains.

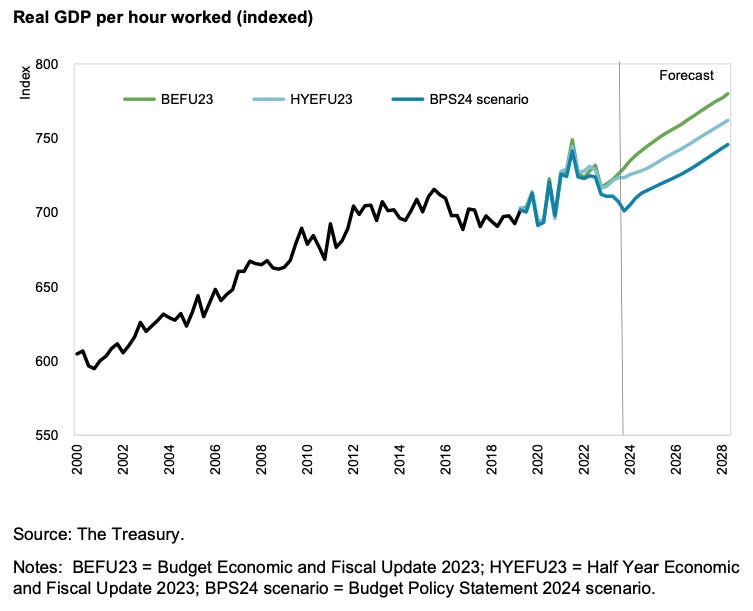

This is the first question to answer because the answers about Government structure, tax levels, infrastructure investment and economic performance flow directly from this answer. It also forces us to have the debate about the inconvenient truth of our nation from the last 20 years: we grew our population very quickly without investing in our productivity. It’s why our real GDP per hour worked has been in recession for two years and has fallen back to where it was almost a decade ago.

I’d like to see a high population growth, high investment growth, high wage and vibrant economy and society that is a stable democracy where we’ve consciously embraced our unique geographic position to become a climate haven deliberately, rather than chaotically and accidentally.

But I know others want to stop the growth and believe in de-growth in the traditional GDP sense. That’s a viable choice, but it has to be taken consciously and after a debate. Currently we assume we’re doing a version of this, but we’re not.

This is just the first. I’ll do more posts with each of the remaining five questions over the next five days:

What improvements on housing, climate and poverty do we want by 2050?

What size and structure of Government spending and debt to GDP is needed to achieve those 2050 targets?

What would an emergency response to achieve the housing targets look like?

What would an emergency response to achieve the climate targets look like?

What would an emergency response to achieve the poverty targets look like?

My initial view

For the purposes of discussion and context, my answers in various forms would be something like:

If we aim for our population growth rate to remain unchanged from its rate of the last 25 years at around 1.5% per annum, that would mean Aotearoa’s population would grow to 7.7 million by 2050, and 19 million by 2100. We are likely to increasingly become a climate refuge for a small portion of the richest 100 million people living within the overall population of 2 billion living in East Asia (China, India, Southeast Asia);

I believe houses should cost no more than 30% of average equivalised household disposable income to live in by 20503, regardless of whether it’s owned4 or rented5.

Aotearoa should aim to reach net zero for climate emissions by 2050, as legislated for currently, with any offsets bought and created in Aotearoa at NZ$150/tonne of C02 equivalent emissions reduced and/or stored permanently, with a broad-based carbon and carbon equivalents tax on all gases rising in $5 per year increments from $50/tonne in 2030 to $150/tonne by 2050, replacing the ETS from 2030.

I think we should hope that no one is in position to say in the Stats NZ Household Income survey they don’t have enough income for rent, food and electricity, and that no one is in a position to say in the survey their house has a major mould problem, or is a major problem to heat;

The size of both central and local Government spending to GDP and net central and local government debt to GDP should be 45% of GDP on average in the 20 years to 20506;

I want Parliament to enact emergency bipartisan legislation (The Aotearoa by 2050 Act (2026)) to create independent agencies answerable to Parliament to achieve the targets above by 2050, just as the Reserve Bank Act was legislated in 1989 and agreed by both major parties to independently achieve inflation of around 2%.

The sorts of policies that could achieve these aims include:

Agreeing a broad-based and low-rate annual Aotearoa by 2050 levy on the value of residential-zoned land of 0.5% for occupied land, 1.0% for unoccupied homes on residential-zoned land and 1.5% for residential-zoned land that is not built on;

Agreeing that Aotearoa by 2050 levy be used to achieve the Aotearoa by 2050 Act (2026), including paying for servicing the debt needed to build the necessary long-term water, housing and public transport infrastructure, as well as maintain the infrastructure;

Agreeing the levy be used to ensure those infrastructure and consenting costs are paid for by the levy and the debt it services, rather than the individual home buyers, land owners, developers or councils, in order to dramatically lower the marginal costs of new homes, and the levy be used to prioritise the building of new homes and public transport networks that dramatically lower housing costs, gross climate emissions and the number of unhealthy homes;

Agreeing that capital gains on real business values and non-residential-zoned land remain tax free and that savings cordoned off until retirement such as KiwiSaver funds do not pay tax on earnings while cordoned off;

Creating a publicly-funded joint job, education, health, food, power, housing and income guarantee for 18-35 year olds, including volunteering and unpaid family caring and community work as choices in that guarantee, and agreeing that the current arrangements for NZ Superannuation of incomes indexed to average wages, no means testing or asset testing and no change in the age of eligibility of 65 also apply to the income guarantee and the age thresholds; and,

Agreeing a fixed and progressive income tax scale for wages, salary, interest and dividend income of 25%, 30% and 35%, where the thresholds rise at the same rate as average incomes;

Agree the GST rate be progressively reduced to 10% by 2050;

Fixing rises in administered prices of Government and council services, including water, transport, rates, publicly leased land and other fees and charges to no more than 2% per annum until 2050; and,

That the Government pay council rates on Crown land and rebate GST on rates back to councils.

Interviewing experts, participants and politicians

I’d look to do individual interviews and arrange Hoons with a range of people through the rest of 2024 and until the local elections in late 2025, to discuss current issues and The Kākā Project of 2026 for 2050 (TKP 26/50), including;

Mayors, councillors and council candidates from all councils and parties;

Ministers, MPs and candidates from all parties in and out of Parliament;

Home builders and Community Housing Providers currently building and/or managing more than 1,000 homes per year;

Bankers, fund managers, insurers and regulators currently financing, insuring and regulating the building, renting and operation of those homes;

Academics, consultants, planners, architects and economists working, researching and teaching on housing, climate and poverty; And,

Authors here and overseas of books on economics, politics, housing, climate and poverty.

This email and podcast was sent to all 21,500 free subscribers in full and is able to be fully shared, read and listened to. Only paid subscribers can comment and vote in the poll.

Nga mihi nui and now we’ve gone past terminal velocity to be a few metres in the air.

Bernard

PS: To do this consistently over the next couple of years, I’ll need to tighten up my daily emails and podcasts so please don’t be too surprised or disappointed if they’re shorter and less detailed. I’ll be dedicating more time to more detailed deeper dives, interviews and ‘Hoons’ for and about The Kākā Project of 2026 for 2050 from now on. If this is not what you want as a paying subscriber, please speak now or forever hold your peace.

This introduction to Muldoon might seem superfluous to people of my generation (I’m 57) and older. He loomed so large in our political view of the world that we often didn’t even bother to explain who he was and what our economy and nation had become. Our generations just used the shorthand phrase of ‘Muldoonist’ or ‘Muldoonism’ as the justification for everything. It was both an insult and a guiding set of ideas or policies to react against and abolish. It meant a fixed currency, Government borrowing overseas with short-term variable rate debt in foreign currencies, Government-decided or guided controls on imports, exports, prices, wages, working conditions, shop-opening hours, high income taxes, much higher public investment in big electricity, gas and oil-refining projects and centralised control of consents for big projects that often over-rode local property rights and enviromental concerns. This approach was often called ‘Think Big’ and that our economy had become a ‘Polish Shipyard.’ As an aside, here’s a February, 2024 review by the OECD of Poland’s shipbuilding industry, which had withered away to 0.1% share of the global market in 2020 from 2.6% in 2000.

Household wealth.

Average annual equivalised disposable income (after tax and transfer payments) increased from $53,192 to $56,919 (up 7.0 percent) in the year to the end of June 2023, with the average cost of housing being more than 40% of disposable income for 18.2% all households (up 2.9 percentage points), with 27.5% of households that did not own their dwelling (up 3.4 percentage points) paying more than 40% of income in housing costs, and 13.3% of households that owned or partly-owned their dwelling (including dwellings held in a family trust) (up 2.6 percentage points) paying over 40% of income in housing costs. There were 617,400 households or 31.4% paying more than 30% of averaged disposable income, Stats NZ reported for the year to June 30, 2023.

Currently 316,500 households or 24.8% of all homeowning households pay more than 30% of income for housing.

Currently 299,900 renting households or 44.5% or renting households pay more than 30% of disposable income in rent.

Both National and Labour have aimed in the past to keep the central Government revenues and debt to GDP at below 30% of GDP, while in the UK and Australia, revenues are closer to 45% of GDP and debts well over 50% of GDP.

Share this post