TL;DR: Here’s the top five news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa-NZ this week, and a discussion above between Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer

Two experts are demanding the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) retract a seminal food systems transition report recently presented to the world at COP28, saying that it ‘seriously distorts’ their work and misrepresents the scientific consensus on the value of shifting to plant-based diets.

This follows a series of earlier reports suggesting that the FAO has been compromised by livestock industry lobbyists and political interference.

It also follows successful efforts in 2022 by some countries, including Aotearoa New Zealand, to have the IPCC water down the language and omit advice to transition to plant-based diets from the influential ‘Summary for Policymakers’ version of their climate mitigation report.

As the livestock industry’s approach to the transition is increasingly being compared to that of fossil fuel interests, pressure is heating up for that sector. A key report has just being released in the US, resulting from the Senate Budget Committee’s investigation into climate delay caused by fossil fuel interests.

Meantime, a key EU nature restoration law is near collapse as farmers protest the bill throughout Europe. Leading biodiversity researchers argue that farmers must be brought along in partnership if the effort is to succeed.

Adam Tooze covers a disastrous year for development finance in his substack Chartbook, as both money and materials pour out of the Global South, and into the Global North, in support of wealthy countries’ carbon transition.

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the video and podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

FAO under pressure over food report

Academic experts Paul Behrens, an associate professor at Leiden University and Matthew Hayek, an assistant professor at New York University, claim the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has ‘seriously distorted’ their work to underestimate the effects of reduced meat and dairy intake on mitigation of agricultural emissions.

According to a report in The Guardian, the academics are calling for the FAO to retract its report, saying it contains systematic errors, lacks transparency and misrepresents the scientific consensus on the value of shifting diets. Pointing to previous reporting, they claim that the FAO has a pattern of misrepresenting the science on dietary shifts.

Behrens posted on LinkedIn:

The FAO presented the first instalment of its roadmap for food systems to achieve zero hunger without breaching the 1.5˚C climate change threshold at COP28 in Dubai. But now Behrens and other academics whose work is covered by the FAO have published an article in the journal Nature Food (paywalled) publicly and explicitly criticising the work. Specifically, they point to the report’s failure to highlight the need to reduce industrial animal agriculture.

“The first instalment of FAO’s roadmap is a welcome step in charting a course towards a zero-hunger, climate-compatible food system. However, several areas for improvement can be identified with regard to both process and substance: the roadmap does not describe how interventions were selected; it does not provide a quantification of the expected environmental benefits of these interventions; it does not include a list of authors and reviewers or details about its review process; and it omits key interventions with demonstrated potential to improve environmental and health outcomes — notably, reducing animal-sourced food production and intake.”

Lobbying & money back agribusiness interests

Ahead of the FAO’s roadmap being published in December last year, the Guardian reported on conflict between the FAO and some of its ex-officials who claimed that the leadership of the organisation censored and undermined them as they attempted to highlight the role of livestock methane in causing climate change.

“Several former staff members compared the power of the agribusiness lobby over FAO policy to that of the oil and gas giants on energy policy. As Green put it: “It is all about money, similar to the fossil fuel industry.”

Between 2012 and 2019, “the lobbyists obviously managed to influence things”, Holstein said. “They had a strong impact on the way things were done at the FAO and there was a lot of censorship. It was always an uphill struggle getting the documents you produced past the office for corporate communications and one had to fend off a good deal of editorial vandalism. You had to accept relatively small steps forward in changing the narrative on livestock.”

The climate impact of food systems received unprecedented attention at the latest COP, and the number of meat and dairy lobbyists attending the meeting exploded in response, to more than three times that of the previous year. According to a subsequent virtual panel of U.S. livestock bosses, reported on by Desmog, they left the meeting satisfied that the industry’s prospects remained positive under the UN’s food and climate plan.

Don’t say ‘plant-based’

The dietary role of meat and dairy is clearly of enormous consequence in New Zealand. In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its Working Group III report on mitigation. The report made clear that switching to plant-based diets is one of the most effective demand-side measures that can be taken to reduce emissions and is also one of the most effective individual actions that individuals can take.

However, during the IPCC summit, at which country representatives approve, line-by-line, the influential Summary for Policymakers Report, a group of representatives from countries that are high producers of meat and dairy worked to water down the language. According to a Newsroom article at the time,

“Coverage of the negotiations by the Earth Negotiations Bulletin – the only media outlet permitted to attend the event – makes clear that New Zealand argued against the use of the term “plant-based” in favour of “sustainable healthy diets” in at least two sections of the report’s summary.

Both dealt with reducing demand for products of high-emitting activities. The first, on how products are presented to consumers, saw “plant-based foods” replaced with “balanced, sustainable healthy diets”. India and Kenya joined New Zealand in removing the reference to vegan and vegetarian diets, while Germany unsuccessfully opposed the measure.”

Research has shown that countries with highly polluting sectors that are also highly trade exposed are likely to hold less cooperative positions in global climate agreements. In other words, the characteristics of the agriculture sector in Aotearoa-New Zealand very likely produces substantial downward pressure on the country’s overall ambition in international climate negotiations. It has also been suggested that climate policy within countries is driven much more by conflicts between more- and less- ambitious domestic sectors over who should bear the costs of the transition, than it is by concerns about the level of action being taken by other countries in the international sphere. Despite this, the study suggests that policymakers will still often rationalise policy choices by referencing the lack of mitigation action in other countries.

The dark PR of big tobacco, big oil, big meat and dairy

Another piece of research featured in the journal One Earth found that the livestock industry was resisting food system transformation using instrumental power and that public funding for food producers was going predominantly to animal farming, while new alternative technologies were being largely ignored.

Despite the urgency to increase food system sustainability, policies failed to address the environmental impacts of animal-based technologies. Powerful vested interests exerted their political influence to maintain the system unchanged and to obstruct competition created by technological innovations.

The approaches being used by meat and dairy industry interests are increasingly being compared to the actions of fossil fuel interests. To understand how powerful industries protect their interests and promote climate disinformation, journalist Amy Westervelt explores the history of the PR industry on her excellent media website Drilled.

“In addition to the violent crackdown on campus anti-war protests we’re seeing across the U.S. this week, there’s also another fossil fuel disinformation hearing happening in Washington, D.C. today, which means another round of social media posts and articles using the phrase: “Big Oil is copying Big Tobacco’s playbook.”

It’s a similar playbook, true, but that’s because Big Oil and Big Tobacco have used the same PR firms for more than a century. To understand some of the tactics and narratives lawmakers are digging into today, it helps to understand how and why the PR industry was created, and how it has expanded to include everything from corporate-sponsored university research and elementary school curricula to statecraft.”

That fossil fuel disinformation hearing follows the release of a joint staff report by the Senate Budget Committee, as they act to revive the House Oversight Committee’s investigation into climate delay caused by fossil fuel interests.

The report details some of the internal documents obtained under subpoena from big oil. The documents from Exxon, Shell, BP, Chevron, the American Petroleum Institute, and the Chamber of Commerce are being released as part of an upcoming hearing titled “Denial, Disinformation, and Doublespeak: Big Oil’s Evolving Efforts to Avoid Accountability for Climate Action.” Some highlights of the report were posted on LinkedIn this week by Aria Koralovich, a senior investigator at the Senate budget committee,

One of the big revelations has been the academic-industry partnerships that have developed between Big Oil and world-leading research institutions, as they worked together to provide, in the words of a Shell representative, “thought leadership and research into technology that could underpin the role for gas.” Similarly, such academic-industry partnerships are being unveiled at prestigious research institutes currently focusing on carbon capture and storage (CCS), in another tactic designed primarily to delay the phaseout of fossil fuels.

There’s more just in on this topic from Drilled: Research or Lobbying? New Documents Reveal What Fossil Fuel Companies Are Really Paying for at Top Universities A new batch of subpoenaed documents show what fossil fuel companies are getting for their university research donations.

Protests push biodiversity deal to verge of collapse

Other news this week highlights the complexity of addressing the environmental impact of the agriculture industry.

Leading biodiversity researchers fear that a new EU nature restoration law will fail unless farmers are brought into partnership. The proposals are on the brink of collapse after months of farmer protests across Europe. Some member states have already withdrawn support for the legislation, according to The Guardian.

“In an open letter, leading biodiversity researchers from across the world said that efforts to restore nature are vital for guaranteeing food supplies – but farmers must be empowered to help make agriculture more environmentally friendly if the measures are to succeed.

The letter, signed by researchers from the University of Oxford, ETH Zurich and Wageningen University, reads: “At no point in history has there been more pressure on farmers. They are responsible for feeding an ever-growing population. And now we want them to save us all from the global climate and biodiversity crises, at the same time as market forces keep making the financial situation harder.

“We desperately need land to support a resilient agricultural sector. We need our policies to empower farmers to be the heroes we need them to be. But to do this, we are also going to need to save space for nature.”

The sad state of sustainable development finance

In the energy industry, the phase-in of renewable energy supply has needed to climb beyond the elbow of the new technology ‘S-curve’ before it was even possible to begin a meaningful conversation about phasing out fossil fuels. In the agriculture industry, there will likewise need to be a significant expansion of investment in both alternative protein technologies and regenerative farming approaches before we are likely to see any traction in the conversation about reducing dietary meat and dairy. At this stage, such investment is relatively small and limited to the private sphere.

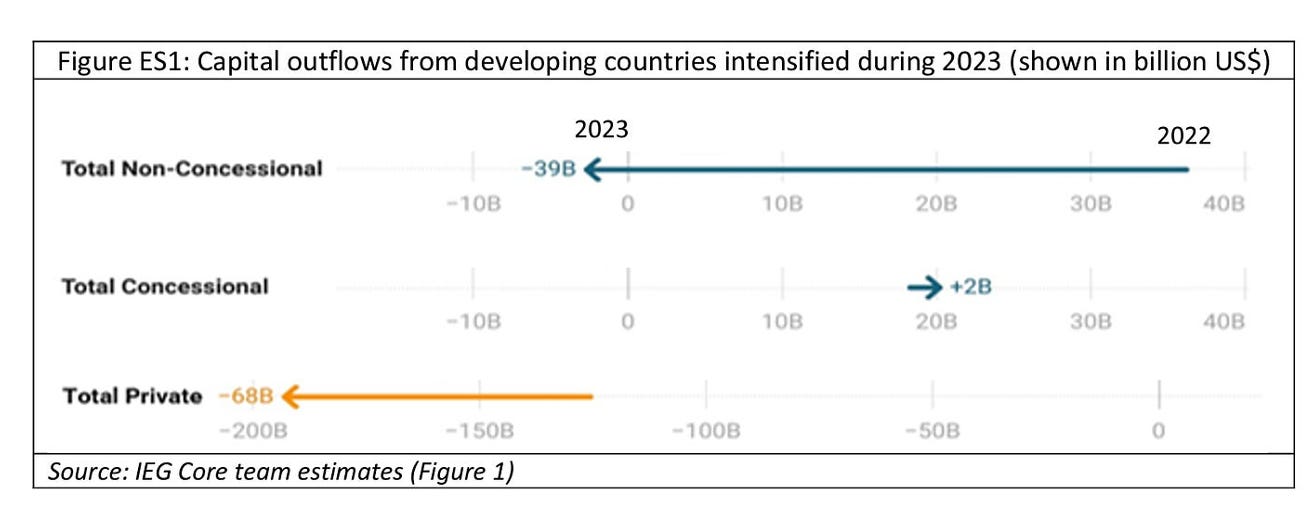

US based political-economic historian Adam Tooze has an excellent article on his substack Chartbook this week, about the state of development finance and efforts to mitigate the climate crisis while assisting poor countries to adapt. The most salient point was summed up in a single graph, showing money pouring out, rather than in, to the Global South, from the Global North in 2022-2023.

“What this shows is that money, both public and private, did not flow into the developing world but flowed out on a huge scale.”

Summarising the state of sustainable development finance, Tooze says

“What the shock of last year proves beyond question is that we don’t have a system that works and merely needs tinkering reforms. The status quo is from the point of view of the developing world profoundly dysfunctional. At moments of global stress it compounds disadvantage and entrenches underdevelopment and it does so to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars. At the macro level, with regard to the most basic questions - how much? to whom? when? - the system is simply not working.”

As a reminder, he points out that global leaders have, for the last several years, promised to accelerate climate financing for the developing world to the tune of trillions of dollars per year. The realisation that finance would reverse course and flow back into the developed world during times of trouble, alongside the millions of tonnes of material resources that flow every year from the Global South to the North to support the carbon transition of developed countries, exposes the profound failures of the current global economic system.

Ka kite ano

Bernard and Cathrine

Share this post