TLDR: Budget 2022 is the Government’s response to calls for help for the ‘squeezed middle’, but also a slight tightening of fiscal policy as it tries to minimise the inflation pain wrecking its election chances.

The ‘rabbit in the hat’ in this Budget is a one-off $350 cost of living payment for those not already getting the winter energy payment and earning less than $70k/year.

The other news headlines include:

a two-month extension of the fuel excise cuts and the half-price bus, train and ferry fares launched in March;

a permanent halving of public transport fares for people with community services cards;

immediate legislation to stop supermarkets blocking competitors from using land through the use of covenants;

a relaxation of the house price and loan caps for first home buyer grants and loans;

just $168m over four years for the Māori Health Authority for direct commissioning of services, which represents just 1.5% of the extra $11.1b being spent on health over the next four years;

a $1.8 billion funding increase for Health NZ and a further $1.3m boost next year to enable it to ‘start with a clean slate’, including ‘cleaning up’ previous deficits of $550m;

an an extra $191m over two years to lift Pharmac’s medicines budget to $1.2b per year, with a focus on funding better cancer treatments;

an increase in dental grants from $300 to $1,000;

an extra $2b in funding for education operating spending and $855m for capital expenditure on schools;

a new $300m affordable housing fund for grants to community housing providers;

an extra $327m over four years to set up the new combined RNZ/TVNZ public broadcaster;

a scrapping of the rule that treats Child Support payments made to beneficiary sole parents as income, delivering an estimated 41,000 parents an average of an extra $24 a week;

replacing the school decile system with a new ‘Equity Index’, with $75m a year in additional equity funding for schools in areas with high socio-economic needs;

an extension of the Warmer Kiwi Homes programme for an extra year, until June 2024, enabling over 26,000 more insulation and heating retrofits for the homes of low income earners; and,

a new Business Growth Fund to improve SME’s access to finance, following the model of similar funds in the UK, Ireland, Canada and Australia, with the Government contributing $100m as a minority shareholder alongside private banks.

Giving cash away without ‘spraying’ it

Meeting the demands of a bunch of magical thinkers was never going to be easy, but the Government has done its best with with Budget 2022, giving some cash to help middle-income voters deal with higher living costs, but not so much that those same voters would think the Government was ‘splashing too much cash’ in a way that would drive up inflation.

Trailing National in the polls and facing criticism it isn’t doing enough to help the ‘squeezed middle’ deal with higher costs of living, the Labour Government has thrown a payment of $350, spread over three months, to those people earning under $70,000 who aren’t already getting the winter energy payment.

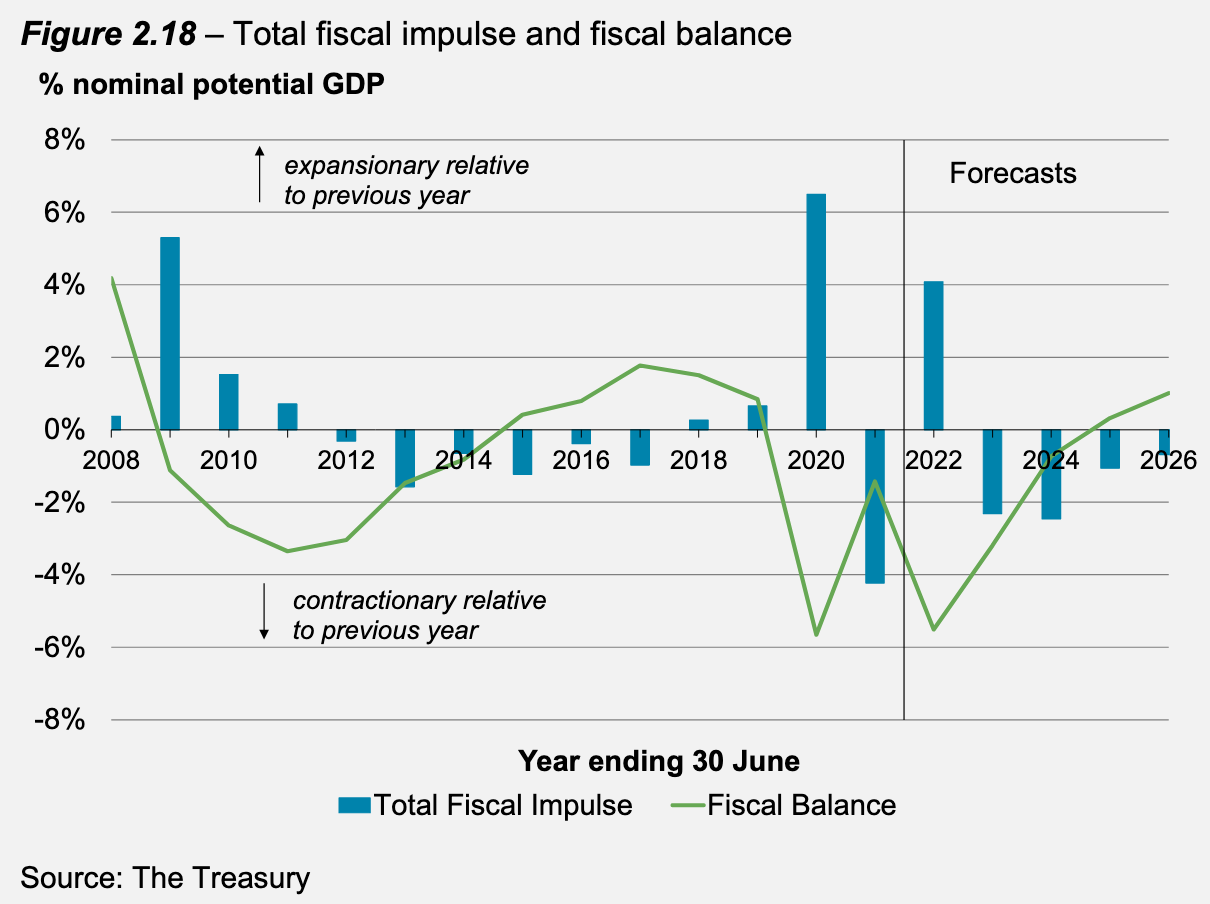

But overall, the Government has restrained its spending in a way that means Budget 2022 actually reduces the fiscal impulse from Government to the economy, and in theory reduces some of the Government’s domestic inflationary pressures that the Opposition is so unhappy about. Budget 2022’s fiscal impulse over the next three fiscal years represents a combined 4.2% subtraction from the economy. That’s more than the combined 3.0% subtraction forecast in the December 2021 Half Yearly Economic and Fiscal Update.

“The fiscal impulse for each year is slightly more contractionary than forecast at the Half Year Update as the Government’s year-on-year contribution to aggregate demand decreases more relative to each preceding year, indicating that, overall,

fiscal policy is dampening inflation pressures.” Treasury in Budget 2022’s Economic and Fiscal Update.

As expected, the Government left its operating allowances set in December broadly unchanged, and did not change its capital allowances. It also confirmed it would reach budget surplus one year later than expected because of slower than expected global economic growth.

Treasury forecast net debt would fall to 15% of GDP by 2026, well below the 30% ceiling set by Grant Robertson earlier this month.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Share this post