TLDR & TLDR: This week I chat with independent economic, political and social researcher Max Harris about the big events of the week, including the Treasury’s slightly more debt-friendly Long Term Fiscal draft, the problem with monopolies and the rise of the rentiers.

Here’s what happened in the last seven days that stood out for me, and why it mattered.

Maybe there’s a way through

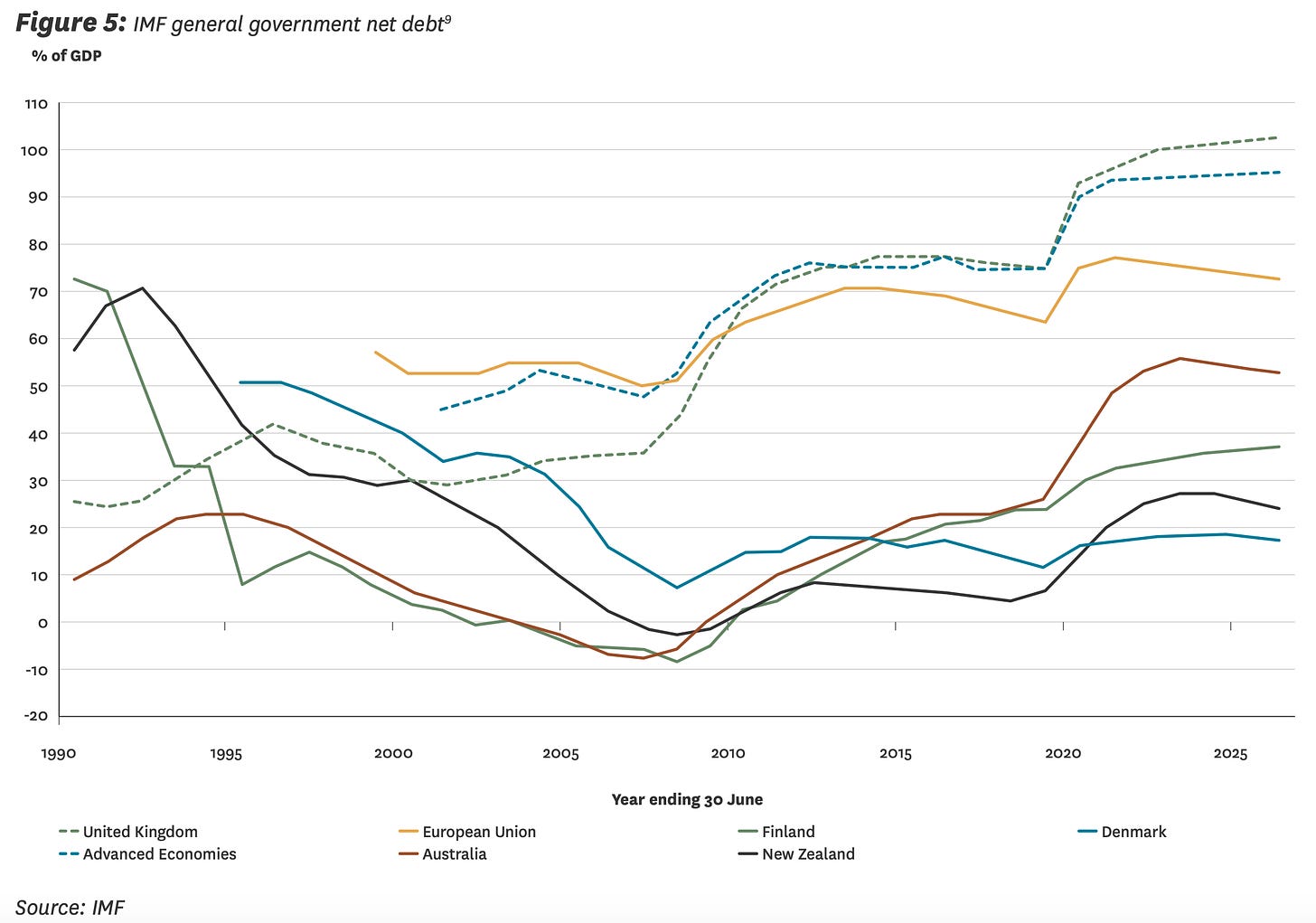

Treasury quietly put out its first draft statement of its once-in-every-four-years Long Term Fiscal Position Statement (He Tirohanga Mokopuna), which did its usual thing of projecting out to 2060 what would happen to the Government’s net debt if the basic policy settings remain unchanged. For years, it has concluded Aotearoa has written itself a health and pension settings cheque that can’t be cashed from about 2040 onwards because the pension and health costs of our ageing population blow out net debt to unsustainable levels (ie the interest costs spiral up to terminal velocity and the Government would default on its debts).

The usual prescription is to water down the pension bill somewhat by extending the retirement age and reducing the pension from its current 66% of the average wage. But this time it also suggested higher taxes, including capital and land taxes, as a potential way through.

The regular exercise highlighted how Treasury’s thinking is evolving and expands on the speech given last month by Secretary Caralee McLiesh, which suggested the Goverment could handle debt well over 60% of GDP and that borrowing could be justified to rectify long term problems such as climate change and housing affordability. The key change is in the Treasury’s interpretation of the word ‘prudent’ in the Public Finance Act 1989’s requirement that the Government reduce debt to ‘prudent’ levels while also thinking about future generations.

McLiesh said that Treasury’s view on the upper limit for debt was dependent on where it thought the Government would default, where the Government wouldn’t be able to access debt markets and, crucially:

“Whether debt is welfare-enhancing: This requires weighing up the costs of higher debt against the benefits of new spending and needs to take an intergenerational perspective. When debt servicing costs are low, or quality of investment high, it is increasingly likely that the benefits of investing to maximise outcomes for current and future generations outweigh the costs.” Caralee McLiesh on June 22.

The bolding is mine. The draft Long Term Fiscal didn’t go as far as it could have in spelling out what type of welfare-enhancing investment could be done, but it did emphasise how strong the Crown’s balance sheet is now, how low our tax levels are relative to others, and the affordability of significantly higher debt levels for much, much longer, particularly with interest rates of below 2%, as they are now.

The Treasury’s changing view does open a way through for any Government to raise a new tax, to invest in welfare-enhancing projects or spending, and to do it while also keeping those supposedly unaffordable health and pension settings.

For example, as I proposed last week in this Spinoff podcast, the Government could impose a 0.5% Affordable Housing and Climate Levy on land values to raise $4b a year, which could service $200b of extra debt for investments in housing and climate infrastructure such as public transport and climate-friendly houses over the next 30 years. I proposed hypothecation of the funds for a new independent Affordable Housing and Climate Commission with a mandate to achieve carbon zero and affordable housing by 2050.

That would be possible under this interpretation of the Public Finance Act, given the likely liabilities of carbon credit purchases and lost productivity from not achieving carbon zero and affordable housing if the investment was not done. I wrote about this in more depth in Tuesday’s Dawn Chorus.

The Reserve Bank could jump the gun with hikes from November

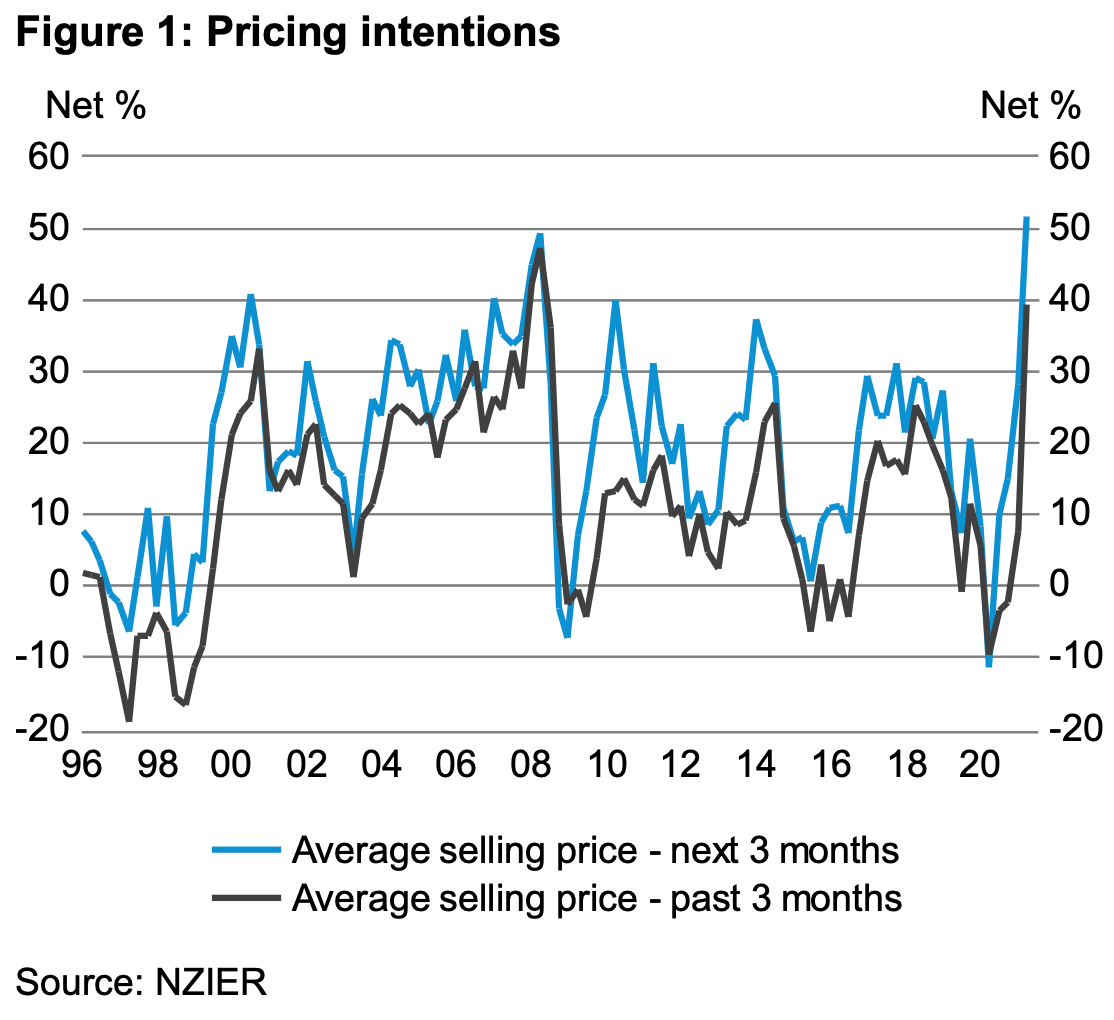

This week NZIER reported its QSBO survey for the June quarter found fast-building inflation pressures because of skill shortages and logistics chain problems. The chart below shows how both pricing intentions and pricing actions have risen to pre-GFC levels. Crucially, price setters were successful (so far) in forcing through the price hikes they had previously said they wanted to do.

A theme of the last decade is price setters have regularly talked big about price hikes and been unable to force them through because competitors and consumers wouldn’t tolerate it. Now, it seems, businesses have some pricing power. We have yet to see proof that workers also now have greater power to force through wage increases, although there are plenty of anecdotes that this is happening.

All four big bank chief economists concluded this meant the Reserve Bank would have to start hiking the Official Cash Rate from November, with one even saying an August start was possible.

The problem is hikes from then would put us way out in front of the rest of the developed world’s central banks and highlights how the Reserve Bank has become more restrictive with its inflation targeting approach than the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Reserve Bank of Australia. They’ve all now adopted a looser way of targeting inflation that tolerates inflation above two percent for a period to offset the last decade of inflation under two percent. It’s called ‘average’ inflation targeting. It means those banks are waiting for actual proof of higher inflation before acting, rather than pulling the trigger early on forecasts of inflation.

I wrote about this in Wednesday’s Dawn Chorus and Friday’s Dawn Chorus, which focused on the ECB’s formal adoption of average inflation targeting. The risk is the Reserve Bank jumps the gun and hikes prematurely, as it has done twice in the last decade, which would penalise exporters just as they’re getting onto a roll.

It’s worth noting that this week Amazon opened up its Australian warehouses to New Zealand buyers and Costco and Ikea are progressing plans to open in New Zealand. The deflationary winds from China’s factories and globalised supply chains are still there, along with the deflation accelerating through the services sectors from the appification of areas such as financial, medical and educational services.

Then there’s the lack of power that labour has to force through wage increases. Unionisation is still minuscule relative to the 1970s, which also lacked the global outsourcing platforms that open up many national markets to global labour supplies.

How soon should we choose to ‘live with it’?

In Covid news, New South Wales’ delta variant outbreak escalated into a widespread lockdown around Sydney and led to brief discussions by the state’s leaders about ‘letting it rip,’ rather than sticking with an elimination strategy. In response this week, Australia halved its arrivals quota from beyond New Zealand to just 120 people per million, less than a third of New Zealand’s arrival limit rate. Airlines started canceling routes that pass through Australia to New Zealand.

But PM Scott Morrison also laid out a four-step strategy to dropping the elimination strategy, dependent on reaching various vaccination thresholds. That is forcing New Zealand to accelerate its planning for something similar.

Also this week, Boris Johnson actually made that call to ‘let it rip’ with a full reopening and the end of many lockdown, mask wearing and social distancing rules in Britain from next Sunday, just as a surge of delta variant cases is arriving in hospitals. He was unrepentant.

“We’re seeing rising hospital admissions, and we must reconcile ourselves, sadly, to more deaths from COVID. In these circumstances we must take a careful and a balanced decision. And there’s only one reason why we can contemplate going ahead to step four in circumstances where we’d normally be locking down further, and that’s because of the continuing effectiveness of the vaccine rollout.” Boris Johnson

Crack down on monopolies to improve productivity and inequality

US President Joe Biden announced this morning a range of measures to crack down on monopolies, which drive up the profit share for the richest and suppress wages for the poorest. (Reuters)

“No more tolerance of abusive actions by monopolies. No more bad mergers that lead to massive layoffs, higher prices and fewer options for workers and consumers alike. Let me be very clear, capitalism without competition isn't capitalism, it's exploitation.” Joe Biden

This is increasingly a theme in the response to rising inequality that is suppressing productivity and causing all sorts of political, economic and financial grief. Just as the use of anti-trust powers by both Presidents Teddy Roosevelt and Franklin D Roosevelt ended the gilded age of the robber barons and oil and railway trusts of the late 1800s and early 1900s, we are having to rediscover the need to stop monopolies throttling capitalism’s strengths and its democratic license.

Biden’s comments this morning were frankly inspiring and I’ve yet to hear anything like it in this part of the world.

“In the early 1900s, President Teddy Roosevelt saw an economy dominated by giants like Standard Oil and JP Morgan’s railroads. He took them on, and he won. And he gave the little guy a fighting chance. Decades later, during the Great Depression, his cousin Franklin Roosevelt saw a wave of corporate mergers that wiped out sec- — scores of small businesses, crushing competition and innovation. So he ramped up antitrust enforcement eightfold in just two years, saving families billions in today’s dollars and helping to set the course for sustained economic growth after World War Two.”

“Forty years ago, we chose the wrong path, in my view, following the misguided philosophy of people like Robert Bork and pullback on enforcing laws to promote competition. We are now 40 years into the experiment of letting giant corporations accumulate more and more power. And what have we gotten from it? Less growth, weakened investment, fewer small businesses. … I believe the experiment failed.” Joe Biden in announcing his executive orders.

Until recently, our own Commerce Commission has seen itself more as a hand maiden for the creation of ever-larger companies in New Zealand, in the misguided hope that scale would bring efficiency and improve productivity. It has left us with major sectors with one to four major players (Supermarkets, Electricity, Petrol retailing, Banking and Insurance) who are able to exercise pricing power to make super profits and press down on wages and supplier prices.

The Government has yet to start harnessing these powers to create more competition and put a squeeze on super profits. To be fair to the Commission, its recent decisions to block the Sky TV-Vodafone and NZME-Stuff mergers showed it is beginning to stir, but the previous approvals of IAG-Lumley and Z Energy-Caltex showed it has a long way to go, in part because legislation set by Government has afforded monopolies too many powers.

What I’m doing this coming week

I’ll be travelling to Christchurch and Hanmer for a speaking engagement on Tuesday, and will focus on my next Spinoff podcast on the failure of the electricity market to make renewable power affordable and attractive enough to deal with climate change.

I’ll be watching for retail sales figures for June on Monday, REINZ house sales volume and price data for June on Tuesday, food and rent data for the June quarter on Tuesday, migration figures for May on Wednesday and CPI data for the June quarter on Friday.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Share this post