TLDR & TLDL: I spoke with Climate Change Commission Chair Rod Carr for my Spinoff podcast this week (see below), but wasn’t able to include the interview because it was on mobile and the audio quality wasn’t great. For completeness, here it is in transcript form below and as a podcast above.

I asked if another unexpected population growth surge over the last 30 years, similar to the one seen since 1991, would blow our climate projections and plans out of the water. He argued it wouldn’t because pure population growth wasn’t the biggest contributor to our emissions growth. He also saw any talk of a population limit or target would distract from the need to get out of our petrol and diesel powered cars, and reduce emissions from agriculture.

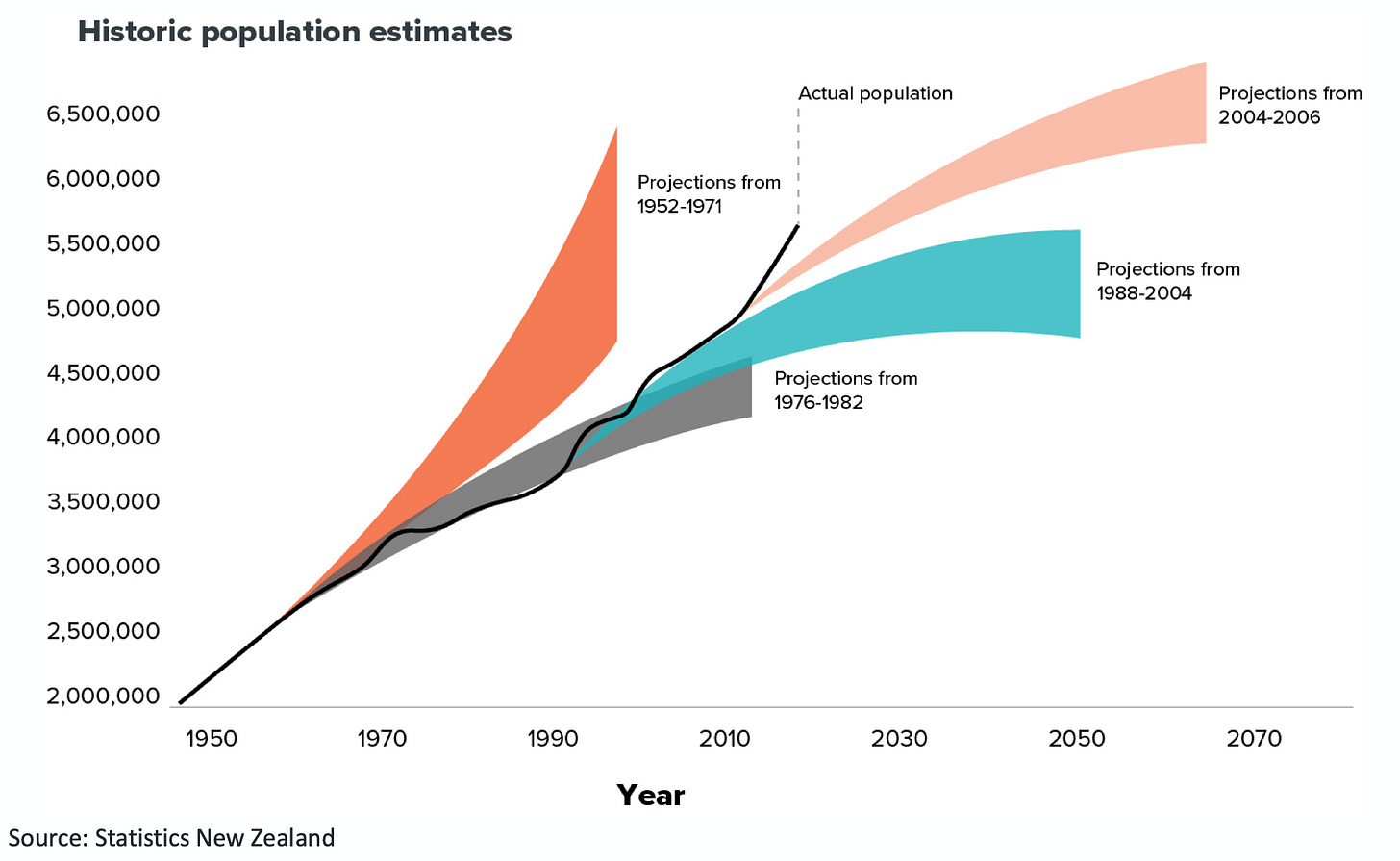

New Zealand’s population rose 47% in the 30 years between 1991 and 2021 , which was double the official population projections from 1988 (see chart second from the bottom). That was because successive governments pulled the temporary migration lever hard around 2002/3 and again from 2013-2020. Our population has ended up about half a million greater than Statistics NZ projected in 1988.

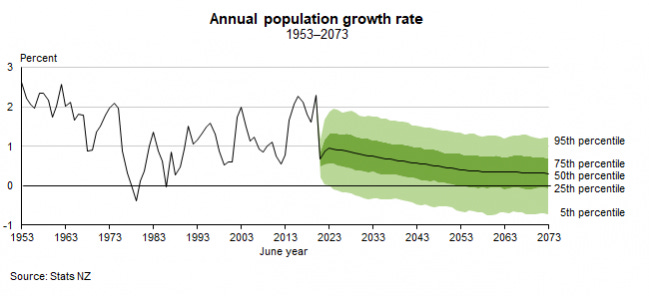

Stats NZ’s most recent median projection was that our population would rise by around 0.6% per year 5.13m to 6.35m by 2053, assuming around 25,000 of net migration each year. Its high net migration of 50,000 a year, which is closer to what we’ve seen over the last decade, would push the population up to 7.36m by then. See bottom chart below of various population growth rates forecast.

The Climate Commission has used Stats NZ’s central projection in its recommendations to the Government. Carr told me even a population of one million above the central projection would not make a big difference to the emissions pathway because most of the emissions reduction needed is in agriculture, and in getting everyone out of petrol and diesel cars.

For completeness, here’s the transcript of the conversation. I’ve edited it for brevity and clarity, and the bolding is mine.

Bernard Hickey: The key thing I'm trying to work out here is how the climate commission sees population growth in its thinking about what we need to do to reduce various emissions. And how much of a risk there is that population growth is much stronger than the official forecasts as they have been for the last 20 years or so?

Rod Carr: I think the first thing is that from the climate change conditions, we took the official demographic projection for New Zealand from the Department of Statistics that are guardians of those long range demographic forecasts.

So we didn't do our own original research and forecasting for New Zealand's population. And if I recall correctly, the assumption is that New Zealand's population grows from the current 5 million to about 6 million by 2050. So that would have been the underlying assumption and what we call our demonstration path, roughly a 20% increase in New Zealand's population over the period from 2020 to 2050.

Bernard Hickey: So in the last 20 years, those official forecasts have been significantly under what we actually got, in large part due to migration. Should New Zealand be more focused on trying to control its population growth, or at least plan some sort of level of migration that would give us what we are expecting as an overall population?

Rod Carr: Let me dial back. This is not Climate Change Commission opinion. It all comes from my experience with the Reserve Bank, when we did ride through those periods where official forecasts and our own forecasts were constantly under estimating the very strong net migration flows. And the other thing the bank got wrong was actually the economic impact that that net migration would have because our assumption was always that essentially, the addition of the population for net migration would add demand more than it would add supply.

Rod Carr: And it turns out for a period in New Zealand history, the new arrivals were adding as much if not more, to supply as they were to demand. And so we've got to be a bit careful when you think about that as what is the composition of the population change, not just what is the total headcount in the population. So that would be the first thing.

The second thing I would say is that you're absolutely right to observe that no matter what New Zealand does, some of these variables are outside our control, unless we prohibit New Zealanders from leaving, or restrict those who are offshore from returning, and COVID has given us a bit of a filter, but largely, we haven't changed New Zealanders’ rights to return, we've just changed how complicated and difficult it might be to exercise that right.

But with a million Kiwis living offshore, if the world does become a less hospitable place, for foreign nationals everywhere, then we may find that New Zealanders are less likely to go abroad, and those abroad are more likely to come home. And that's beyond our control unless we have some pretty restrictive and new policies about rights of leaving and rights of returning.

So set that to one side: you could then use the visa programs to better control who comes and how long they stay. And I think that is a sensible part of policy. But it always has been. Whether it's been used as effectively as it could be or should be, I'm not quite certain.

But certainly, you don't have a right as a foreign national to turn up and work in New Zealand and there are rules about how many can come and how long they can stay and what you have to do to get on the pathway. So the question becomes not so much should we control that, but to what extent should we control that?

And then I think you come to the links with climate change. The planet doesn't care where you were born. So if New Zealand is absorbing people who would otherwise have lived and emitted somewhere else, then the challenge in nationally determined contribution terms is that we become responsible for their emissions and the country they left is no longer responsible for their emissions.

But that's a relatively small proportion of all global emissions. So if we look at New Zealand, the number of migrants that come in and out of New Zealand or the number of New Zealanders who leave and return makes no difference to the heart of our greenhouse gas emissions attributed to, essentially, agriculture. And then if you look at what is driven on a per capita basis, transport emissions are driven more by mode of transport — what we choose to drive — rather than how many of us are driving.

And the decarbonisation of medium and low temperature heat is not a function of how many people are in the country, as much as a function of how we generate the energy we need in order to undertake those processes.

While it is true that a proportion of all our emissions relates directly to the number of us in the country, it is a relatively small proportion of our total emissions.

Bernard Hickey: There is a chance that climate change drives climate refugees from the South Pacific to New Zealand. We have a zero carbon target for 2050 and some nationally determined contributions, along with in theory, potentially some liabilities for carbon credits down the track. Can we hit our zero targets and avoid big carbon credit liabilities if we have a significant numbers of people come in?

Rod Carr: Let's put that in the balance, so let's say, instead of the population pathway, that is in the demonstration path of plus one million, we've got an extra million over and above that, which would be pretty dramatic, right? I mean, that would be saying that the population was going to grow by 40% over the next 30 years. But let me say that that extra million people might contribute between, say two and three million tonnes. So we might add two or three million tonnes of admissions. And our current gross emissions are 80 million tonnes.

Rod Carr: So what I'm a bit fearful of is people using climate change as a rationale for population and migration controls, partly taking their eye off the real prize here, which is all about gross emissions reduction through behavior change from us, about us.

So yes, that could be a contributor, but the biggies are how we think about stabilizing global warming from greenhouse gas emissions and agriculture, and how we get to net zero without planting trees everywhere, which is about reducing fossil fuel use in the economy.

And there's a bit of a danger that we could get there easier, or we would face more risk, but for the fact that we should have tighter immigration, and I am concerned if you take that path, that you are allowing the conversation to get away from the one that really matters, which is how do we reduce these gross emissions from the way we go about our lives, and the products that we produce and the services we demand.

Rod Carr: The thing to just keep in mind is the Climate Change Commission itself has taken the official estimate. And within that construct, the population increases from five to six million. We didn't specifically model sensitivity to different population pathways.

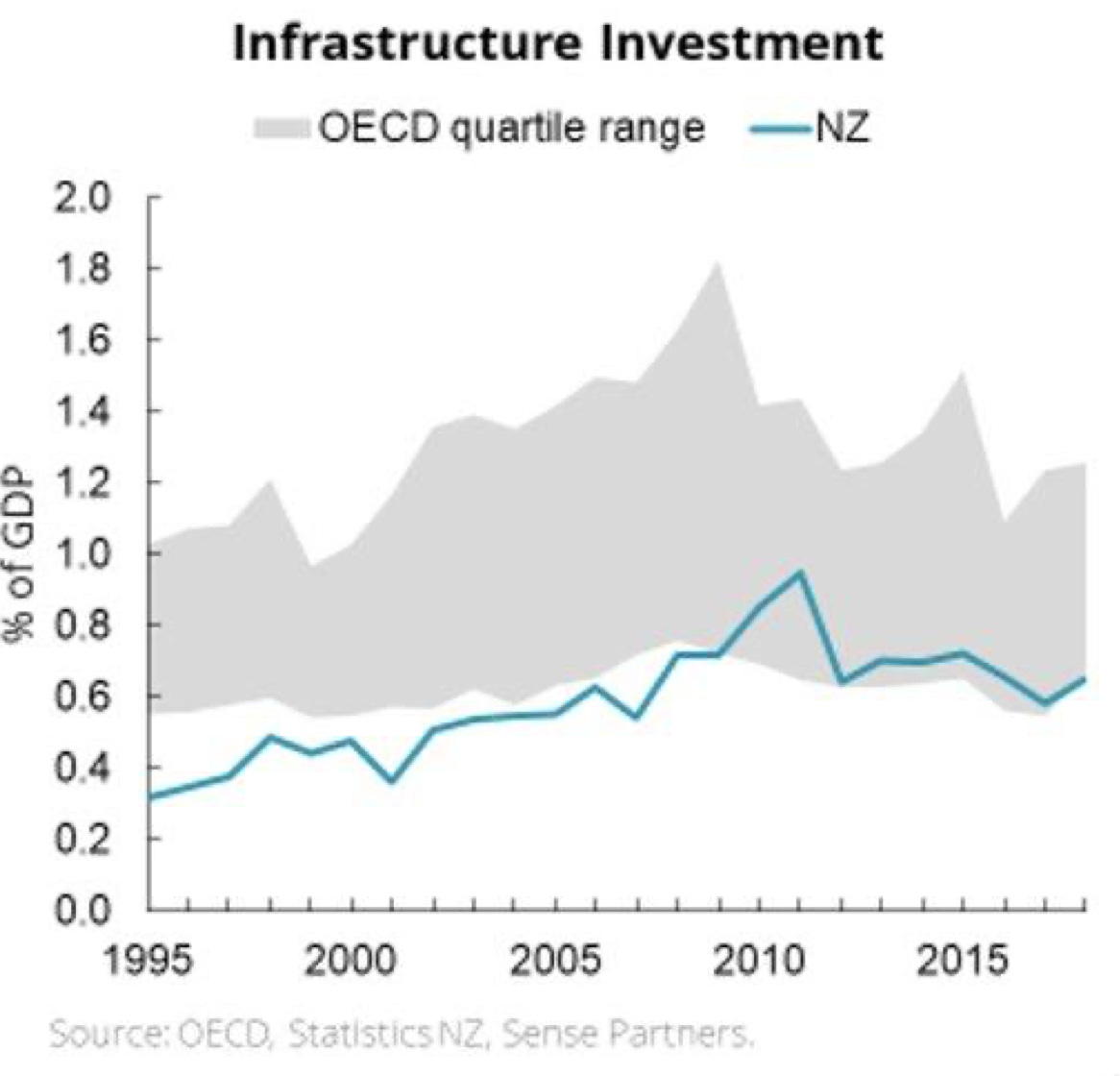

I made the point in the Spinoff podcast that our failure to properly forecast population growth because of decisions to ramp up temporary migration has meant our infrastructure investment has been much lower than expected. It helped create a situation where both central Government and Councils reduced investment levels over the last 30 years to allow lower Government debt (which produces the politically popular combination of low interest rates low and high house prices) and lower taxes.

In the podcast, I asked whether another unexpected population surge that did not have matching infrastructure investment would make it impossible to solve our housing affordability and climate change crises, and meet our Treaty of Waitangi obligations.