TLDR & TLDL: The Reserve Bank has rejected accusations it is responsible for a 34% explosion in house prices over the last 18 months, saying it was only a ‘bit player’ in a market bedevilled by supply side problems and tax advantages it was not responsible for fixing.

But I argue below this view downplays the central bank’s enthusiastic adoption of unconventional monetary policy (money printing to buy bonds) at Fed-like levels, and ignores its now-reversed decision to completely remove restrictions on riskier mortgage lending. It denies responsibility, but the Reserve Bank actually made a political decision with the agreement of the Finance Minister to increase the wealth of the wealthiest to stimulate the economy.

It worked to cushion the worst economic shock in our history, but it also permanently widened wealth inequality massively. They were advised of the effects and there were alternatives, but went ahead anyway and are now trying to shift the blame to others. That’s a pity. They’re not fooling many, and there will be an eventual political reckoning when the generation locked out of their futures work it out.

In news breaking overnight and this morning in our political economy:

Aotearoa-New Zealand signed up overnight to a global pledge to reduce methane emissions by 30% between 2020 and 2030, which effectively triples the nation’s current official commitment to reduce biogenic methane emissions (ie from cows and sheep) by 10% between 2017 and 2030 (Rod Oram) As recently as last week, James Shaw would only say the Govt was considering joining the pledge (Reuters). Achieving a 30% reduction in eight years would involve major reductions in dairy herds and output with current technologies;

PM Jacinda Ardern said after a flying visit to Northland (the top half of which was put back into level three last night after a mystery case was found) she would visit Auckland next week;

House price inflation re-accelerated to a monthly rate of 2.1% in Oct from Sept and annual inflation was 28.8%, CoreLogic reported last night, saying it was due to lockdown-related shortages of new listings and continued strong demand.

Coming up later today, I’ll be covering the Reserve Bank’s Financial Stability Report and labour force data due later this morning, and then the US Federal Reserve’s decision due overnight on whether and how fast to reduce money printing ahead of rate hikes next year or 2023.

(Normally, the section below in my daily email is only for paid subscribers. But I’ve decided to open it up to all free subscribers and new readers, given the level of public interest in housing. If you think this sort of explanatory and accountability journalism is useful for the public in the long run, I’d welcome your support as a paid subscriber to keep my focus on housing affordability, climate change and inequality financially sustainable.)

‘A bit part.’ Really?

The Reserve Bank yesterday rejected accusations it was responsible for a 34% explosion in house prices over the last 18 months, saying it was only a ‘bit player’ in a market bedevilled by supply side problems and tax advantages it was not responsible for fixing.

Governor Adrian Orr used a long speech on Tuesday to essentially throw the blame in a gentle way back at the Government and Councils for allowing or creating the land, labour and building materials shortages that made it difficult for housing to respond to demand shocks. Orr also nodded to the tax incentives for people investing in housing as an asset and recommended home owners look at diversifying into other assets because house prices currently unsustainable.

Orr delivered the speech the day before the bank’s half-yearly Financial Stability Report was scheduled to detail the sustainability of the banking system’s exposure to the $1.5t housing market and just before news the housing market accelerated again in October (see above).

Here is the core of the bank’s argument (bolding mine):

“Movements in interest rates do affect the demand – and ultimately the price – of housing assets. However, it is mostly the long-term trend in interest rates, as opposed to short-term changes in rates related to monetary policy. The secular decline in global interest rates over recent decades has driven asset prices – including house prices – up globally.

“The extent to which New Zealand house prices have reacted to changes in housing demand is mostly related to the inability of housing supply to respond. Houses have been scarce at a time that demand was strong. The reverse is now evolving – with housing building at record levels at a time that population growth is static.

“We expect to see an easing in house prices over the medium term as a result of these supply-demand dynamics. This means house prices would be moving back toward a more sustainable level – a level that can be explained by underlying economic fundamentals.

“The move toward more sustainable house prices will be incentivised by slowing demand – as an outcome of higher interest rates and low population growth, and an increase in space to build. The recent Government announcements on reducing urban building restrictions is significant in terms of adding to the ‘space to build’.

“The role of the Reserve Bank is a ‘bit part’. We are one cause of demand changes as we alter interest rates to meet our monetary policy Remit. We also work to limit mortgage lending when it appears excessively risky. However, this is more about limiting the damage to banks’ balance sheets, rather than altering overall demand.” Adrian Orr in a speech via Zoom to the Property Council of New Zealand Retail Conference in Auckland.

So what didn’t the speech cover?

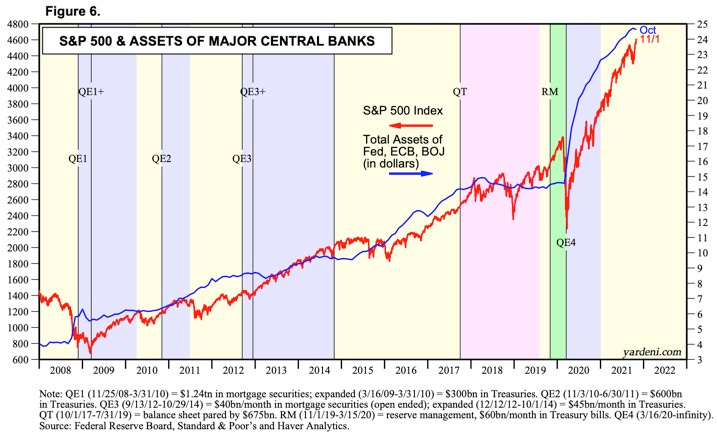

But the speech glossed over the bank’s active decision in March last year to print more than $50b to buy Government bonds in a way that lowered mortgage rates, just so it would inflate asset values and create a ‘wealth effect’ to bolster consumer spending.

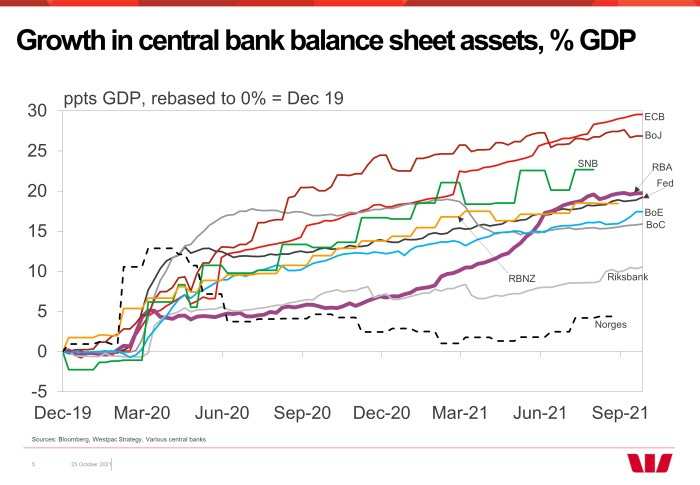

The Reserve Bank printed just as much as the US Federal Reserve, relative to the size of our economies, in the months after the Covid outbreak (See chart showing yellow line of NZ and black line of Fed). The Reserve Bank actively decided to make already-wealthy home owners wealthier as a way to boost consumer spending and the economy.

It worked to cushion the blow of Covid, but did it at the expense of a massive widening of wealth inequality, and in the process destroyed the hopes of a whole new generation of first home buyers, given they know prices can now never be allowed to fall fast by the Reserve Bank and Government, for monetary policy and political reasons.

That generation has seen how central banks and Governments have repeatedly bailed out banks and chosen to use monetary and fiscal policy to protect and pump up the value of assets. It’s the reason why so many young people are investing in stocks. They want to get in on the free money too. They can’t afford a deposit on a house, so the best way to get exposed to the free money is by investing in stocks.

The $549b wealth effect

In my view, to somehow suggest that the bank’s actions somehow didn’t matter over the last 18 months beggars belief. It deliberately used the housing market as a monetary policy tool, which effectively meant it was making a political decision to enhance the wealth of two thirds of households to increase consumer spending. It may argue it had no other choice because it could not cut rates below 0% (as bank computer systems couldn’t handle it) and banks weren’t lending to businesses, but it could have thrown the choice back into the publicly accountable lap of the Government and told it to use fiscal policy in a more direct way (see below).

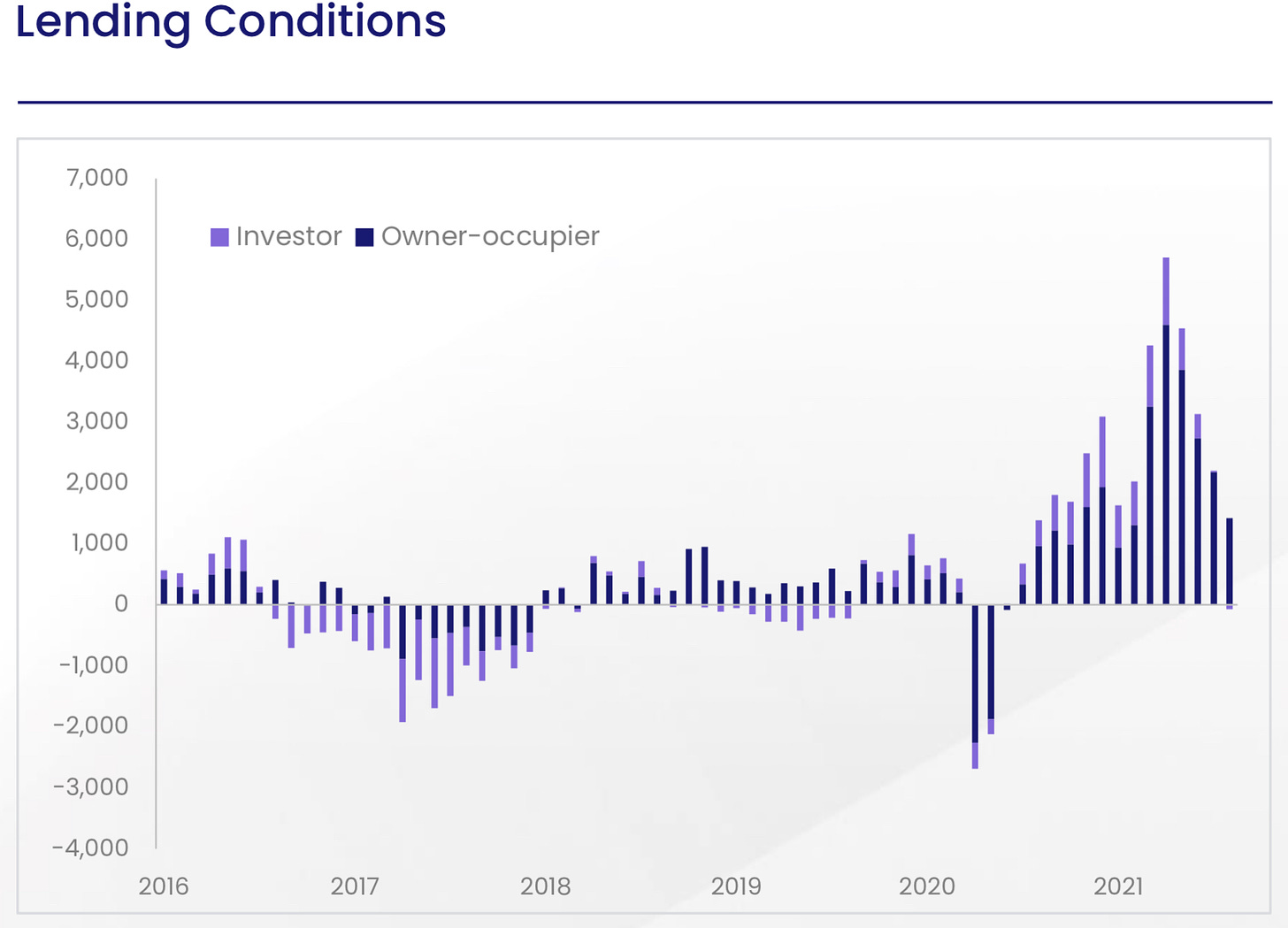

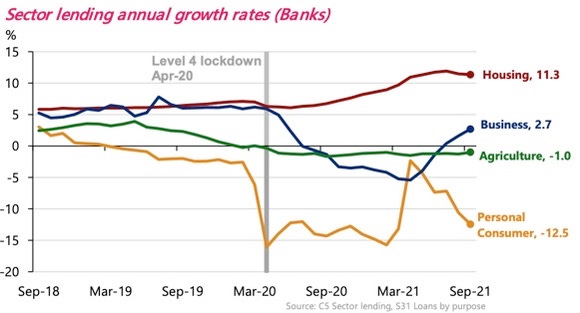

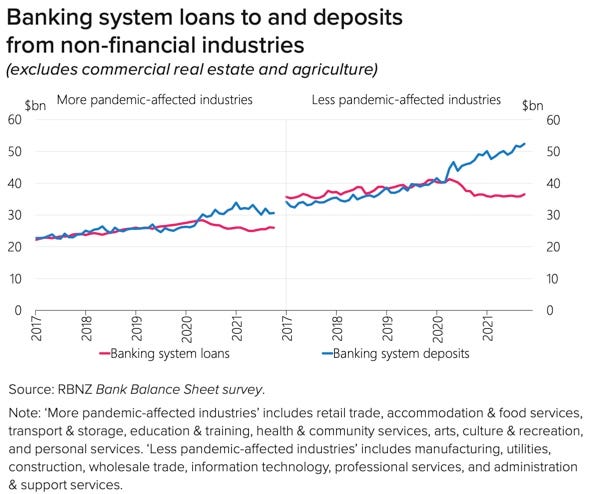

Instead, an independent arm of Government with the agreement of Finance Minister Grant Robertson created money and relaxed lending restrictions in a way that increased the wealth of home owners by $549b to $1.74t (that’s t for trillion) over the course of the pandemic. The Reserve Bank’s actions unleashed a torrent of bank lending that pushed up the value of existing homes. Banks cut their lending to businesses and reduced their lending to back residential property developments.

There was an alternative

The fairest and much more effective way to immediately boost consumption would have been to make large and equal cash payments to all residents. It would have been much cheaper, fairer and would have done much less to widen inequality. Most of the grants would have gone into consumption, given those on lower incomes have to spend a higher proportion of income consumption. The Govt and Reserve Bank would have gotten more stimulatory bang for their buck with so-called ‘helicopter money’.

Instead, the Government (in the form of Government Covid spending and Reserve Bank actions) chose to pump up asset values for the already wealthy, who have a lower propensity to spend and a higher propensity to save, and to give cash to business owners, who are mostly the same people owning property.

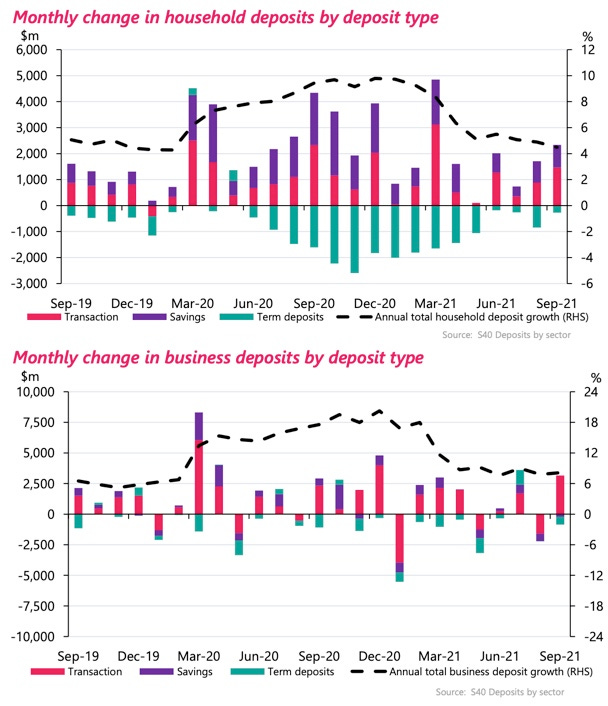

The Govt gave $18b (and counting) of cash payments to businesses (without means testing, document checking or auditing) with the aim of keeping workers from being sacked, but it chose not to proceed with direct cash payments to all residents, as happened in some other countries and as suggested by some officials. That $18b has ended up almost totally in non-financial business and household savings accounts, rather than being spent.

Non-financial deposits rose from $89.8b in Feb 2020 to $110.2b in Sept 2021, while household deposits rose from $184.5b to $209.1b. Retail spending, however, rose just $2.3b to $152.7b in the 18 months to the end of June from the previous 18 months.

In effect, the Govt’s stimulus spending of at least $18b in cash grants, plus the Reserve Bank’s $57.6 of money printing to buy Government bonds, generated an extra $549b in wealth for property owners, an extra $45b in business and household deposits in banks, and an extra $2.3b in spending (although it could be argued the counterfactual would have been a sharp fall in retail spending).

This chart shows how bank lending to businesses fell sharply during Covid, while they increased lending to home buyers, and how the $18b of wage subsidies ended up in term deposit and transaction accounts of home owners and businesses.

But the bank knew the wealth effect was a blunt instrument with diminishing returns.

The bank’s own research from 2019 shows that every $1 rise in household wealth generates three extra cents in spending. So far, that would mean the $549b extra in household wealth from housing would have generated an extra $16.5b in retail spending. It’s unknowable what retail spending would have been without the money printing and bond buying, but the Reserve Bank appears to have gotten poor stimulative value for its money, while also dramatically worsening wealth inequality.

A changing tune on using the ‘wealth effect’ as a monetary policy tool

The Governor may have argued in yesterday’s speech that the bank did not and would not target price levels in housing, but its actions last year showed it definitely saw rising house prices as a feature, not a bug, of its monetary policy.

Here’s what Orr said in a speech to a Victoria University seminar on Sept 2 last year (bolding mine):

“We do acknowledge that low nominal interest rates for a long time will support asset prices, will lead to a sense of increased wealth and hence a higher desire to spend and invest. That is one of the channels of monetary policy and is a deliberate outcome … we are more than comfortable accepting that risk and being aware and talking openly of it and round what policies might mitigate and manage these types of risks but our first and foremost best effort that can be made to wellbeing at the moment is around supporting job security." Adrian Orr at 37 mins

He went on to say if the wealth effect pumping got too much, the bank could use its other tools such as lending restrictions to quieten things down.

“We as a central bank need to be aware of well…are those asset prices being unnecessarily inflated, are they going beyond any sense of fair value, and what would a sudden adjustment in those asset prices, a fall in prices, imply for the financial system as a whole and that’s where we have our prudential tools….high and persistent unemployment keeps me awake, not house prices.” Orr at 51 mins

The tone of yesterday’s speech was very different, and the Governor’s comments at select committee hearings has also pushed back at the idea the Reserve Bank contributed to the 34% rise in house prices, at a time when migration collapsed, the economic suffered its biggest shock in almost 100 years, and housing supply grew at its fastest pace since the early 1970s.

Here’s Orr in yesterday’s speech (bolding mine):

“With regard to using interest rates to target house prices, this is not in our mandate - nor does it make sense. Monetary policy is best used to manage overall consumer price inflation stability i.e., an aggregate consumption price index, rather than being used to target a specific asset price. Likewise, trying to target both consumer prices and house prices with monetary policy will quickly lead to confusion and suboptimal outcomes.”

“In summary, our monetary and financial stability tools do not increase the ability to supply more houses in response to changes in housing demand, and they only – very indirectly – incentivise broader investment awareness and portfolio diversification.” Orr in yesterday’s speech.

The bank could argue it did not target a particular level of prices, but it certainly wanted higher house prices last year.

You want us to diversify? Seriously?

Another feature of yesterday’s speech was Orr’s recommendation home owners look to diversify into other asset types.

He is not the first Reserve Bank Governor to warn households their houses were over-valued and they should worry that higher interest rates will cause them losses.

Here’s his comments in the speech (bolding mine):

“The recent extraordinary rise in Kiwisaver balances has been outstripped by recent house price increases. The benefits of diversification are not being fully overlooked by New Zealanders. But the weight of money is still favoured toward housing – helping drive house prices unsustainably higher.’

“Property will always be an important asset class in a well-diversified investment portfolio. However, there are strong grounds to believe that in New Zealand many of the associated risks have been inadequately priced, identified, and managed. As such, New Zealand households continue to hold uncompensated risk and are overly exposed to mortgage debt.

“This investment preference has worked well over time for many. However, this is not the case all of the time, for all people, and compared to all of the benefits that a more diversified portfolio will provide for the same or less risk.” Orr

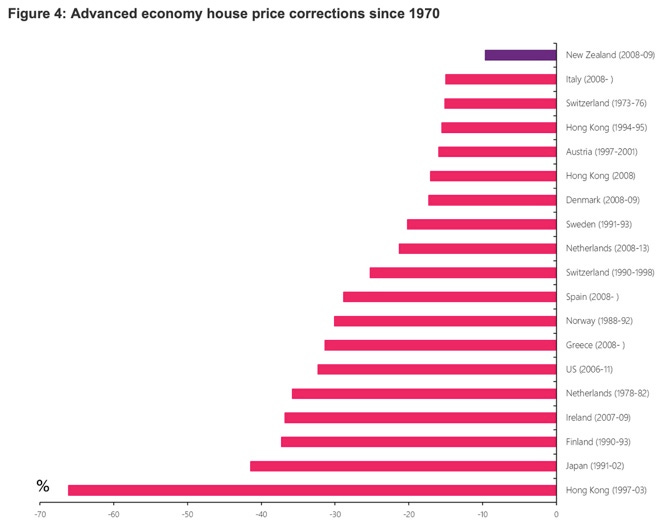

However, the Governor himself undercut that argument in showing how New Zealand’s house price corrections have been the lowest in the world, with this chart in the speech.

He also has to contend with a history of Reserve Bank Governors warning households of lower house prices and higher mortgage rates, only for house prices to double and treble in the coming decades and for mortgage rates to more than halve.

A house price expectations credibility issue

The Reserve Bank has worked hard and won the battle to keep CPI inflation expectations around the middle of its 1-3% target range. But it has been less successful shaping them for house price expectations.

Here’s a hit parade of central bank Governor’s comments over the years:

Reserve Bank Governor Don Brash in April 1998:

“Far too many people still see getting heavily into debt to buy a second property as the best way they can save for their retirement, even though, in my view, they will be disappointed.” Don Brash.

House prices have risen 411% since he said that.

Brash then said in August 1998 house prices were likely to rise in line with other inflation of around 2%:

“Property investment is not a low risk activity in a low inflation environment, and urging people of limited means to borrow heavily to undertake it puts them at risk of serious loss in today's circumstances.”

House prices have risen 409% since he said that.

Reserve Bank Governor Alan Bollard said in September 2003 after house prices rose 14% in the previous year that rental property investors should soon expect real deflation:

“I'm concerned that this could end in disappointment, especially for unsophisticated investors rushing to get on the housing investment bandwagon.” Bollard.

Prices have risen 278% since he said that.

Bollard said in Sept 2004 the success of housing as an investment depended on the prospects for capital gains in the coming years because yields from rents were so low:

“A reasonable view is that house prices are unlikely to rise much further over the next two years, and some falls are certainly possible, particularly in some regions,” he said.

Prices have risen 226% since he said that.

Bollard told central bankers in Switzerland in June 2006 that New Zealand house prices would start falling by the end of 2006 as higher interest rates took effect. House prices have risen a further 159% per cent since he said that.

Reserve Bank Governor Graeme Wheeler warned in February 2015 there could be a sharp correction in house prices.

Then PM John Key supported that warning, saying:

“We are building a lot of houses in Auckland now. People can get a bit carried away with the fervour of these things and believe it is all going in one direction. History shows you house prices go up and down.” John Key

Finance Minister Bill English also said then:

“There's no asset price that can go up at over 10 per cent a year forever, so sometime it will stop. And in this case we are really starting to get more supply coming at speed into the market.” Bill English.

Prices have risen 88% since they said that.

Wheeler said in March 2017 Auckland house prices faced a heightened risk of a sharp correction because of the risk of higher interest rates and the number of homeowners with high debt-to-income ratios.

Prices rose another 56% after he said that.

House prices have risen an average of 20% a year for the last 20 years. Investors currently see house prices rising 6-7% per year or doubling every 10 years, as this ANZ Consumer Confidence chart on expected house inflation over the next two years shows. They have been much more right than the central bank Governors.

There is also an unacknowledged moral hazard problem

Home owners have seen twice in the last 15 years how the Reserve Bank and Government have intervened to protect the housing market when it looked like falling substantially. Understandably, they don’t believe these warnings or pleadings to diversify, particularly when they are able to leverage up their outsized gains, unlike with other investment decisions.

Apart from one short period after the arrival of Covid in February/March last year, investors have seen house prices rising 6-7% a year every year into the ad-infinitum. That implies house prices would double every decade or so.

Interestingly, an analytical paper put out yesterday by the Reserve Bank on measures of house price affordability and sustainability used consumer expectations of consumer prices, rather than investor expectations of house prices

I’d suggest the Reserve Bank challenge its own assumptions about what investors think about future prices, and ask the public whether it thinks the Reserve Bank and the Government have built a too-big-to-fail housing market that they can’t allow to fall for political and economic reasons.

Also, interestingly, the Reserve Bank’s own research shows that any attempt by the Reserve Bank to do a ‘reverse wealth effect’ to slow the economy would have quite an impact. Here’s the paper referred to above, which gives a sense of the feedback loops involved and how this is a difficult tool to put down (bolding mine):

“Our empirical results show that, on average, the marginal propensity to consume out of housing wealth is about 3 cents out of one dollar, but it is larger in responding to negative shocks than positive changes in housing wealth. We further investigate the role of household indebtedness in accounting for the asymmetric effect. Our findings suggest that household leverage reinforces the housing wealth effect in a housing bust, but dampens the housing wealth effect in a boom.” Reserve Bank paper.

This emphasises the diminishing economic returns of flogging the housing market to stimulate the economy and raises questions about what the Government should do next time.

Yesterday’s speech showed the Reserve Bank does not think there is a problem to solve. I think there is.

Ka kite ano. Have a great day

Bernard

Share this post