TL;DR: The key news in Aotearoa’s political economy today includes:

National appears set to push councils to move their water assets off their balance sheets in a very similar way to Labour’s Three Waters plan, just without the co-governance and as much compulsion, but still with the flawed idea that somehow off-balance-sheet borrowing is actually better for taxpayers and ratepayers in the long run than facing up to the fact that higher taxes, charges and public debt are needed to fund fast population growth;

Failed online supermarket operator Supie has named Fonterra, Tatua, SC Johnson and Mars as suppliers who refused to use the wholesale supermarkets regime designed to allow competitors access at the same reasonable prices as the duopoly of Woolworths and Foodstuffs, proving yet again that finger-wagging at monopoly power is pointless, and shows the last three years of prevaricating over structural separation or a forced partial sale was wasted;

Officials warned the Labour Government in September that Aotearoa is set to miss its Paris target commitments by 114 megatonnes of emissions by 2030, which would have to be met by buying international emissions credits at a cost of up to $26 billion, yet none of this is included in Treasury’s contingent liabilities in the Budget;

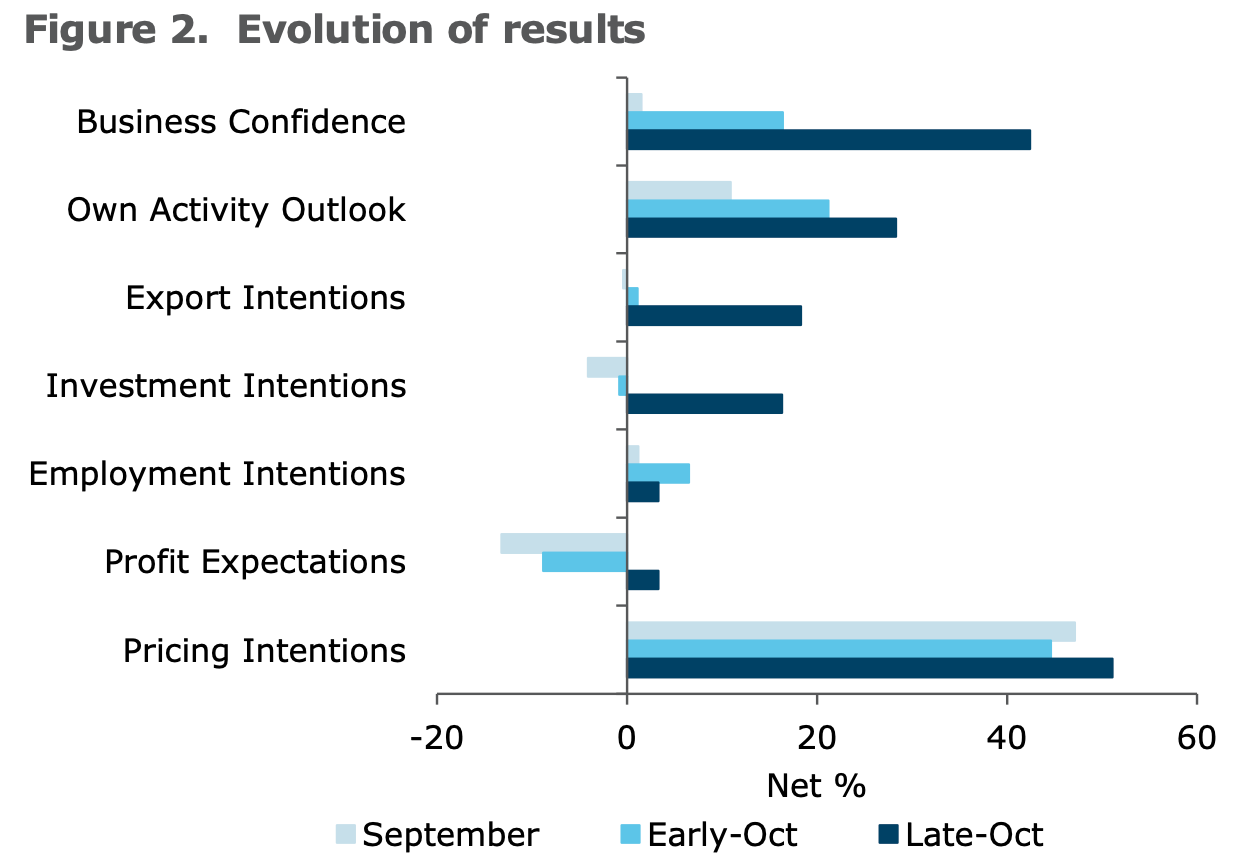

Business confidence about the wider economy exploded back to 2017 levels after National won the election on October 14, although businesses’ confidence about their own activity improved too, just not by as much, which shows again how dependent on who’s in power the wider measure is, while the own-activity measure is more closely aligned with GDP growth;

Building approval numbers show there were 17,079 homes consented in the year to June 30 this year, while over the same period Stats NZ estimates Auckland’s population rose by 48,000, which means Auckland’s housing shortage clearly got worse, given many of those consents are replacing homes that were bowled; and,

The number of patients waiting to see a specialist longer than they should rose 46% in the last year to 51,274, Te Whatu Ora data shows, indicating severe stress is growing in a hospital system labouring under a sinking lid vs population growth and health cost inflation for three decades, as is necessary to keep core Government taxation under 30% of GDP.

Paying subscribers can see more detail below the paywall fold and hear more of my analysis in the podcast above.

‘I don’t care, just get the pipes off their balance sheets’

National and ACT campaigned before last month’s election to repeal Labour’s Three Waters legislation, but likely Infrastructure Minister Chris Bishop is now shaping up to keep much of the financial architecture underpinning Labour’s reforms.

That is leading National and voters down the same politically complicated and misguided route as Labour — towards higher public charges and higher debt that is actually taxpayer debt, even if ministers, mayors, councillors, ratepayers and voters pretend otherwise. And it’s all because we believe we can have clean water, high population growth, low taxes and low debt. All at once. Keep reading to find out what I think that’s impossible, but first the news.

Bishop told Newsroom’s Jonathan Milne in an article published yesterday he also wanted councils who couldn’t afford infrastructure to shift them off their balance sheets into new vehicles that are able to borrow.

He draws a contrast with the example of Wellington Water, where six councils have set up a regional organisation but retained ownership of the assets, debts and revenues.

"I don’t care what it is called but I want the assets off the councils and into a new organisation, with the quality and price regulation in our model," Bishop tells Newsroom.

"Wellington Water exists now and they pretend it’s a council-controlled organisation, but Hutt Council owns its pipes, Upper Hutt owns its pipes, etc."

Allowing new council controlled organisations to borrow on their own behalf doesn’t necessarily mean that National just sticks with the three Three Waters organisations set up under the existing legislation. Jonathan writes National is looking at three options to replace Three Waters.

National has allowed itself more than just the 100 days to draft replacement legislation, by challenging councils to deliver a plan for how they will transition their water services to a new model that meets water quality and infrastructure investment rules, while being financially sustainable in the long-term.

There are three that broadly fit within the policy principles upon which National campaigned:

a framework designed by economic consultants Castalia on behalf of Communities 4 Local Democracy;

a finessed version developed by Malcolm Alexander and a technical working group commissioned by the Taxpayers' Union; and,

a regional model championed by five Hawkes Bay councils.

All three return the decision on the new structure to local authorities; all three propose a degree of regional collaboration to best-use local expertise and achieve economies of scale; and all three contemplate placing assets in the ownership of council-controlled organisations.

So why take the assets off council (and Crown) balance sheets?

This begs the question of why take the assets off balance sheets, but leave them in council ownership, given the biggest credit ratings agency, Standard and Poor’s, sees these separate bodies as pseudo council assets anyway, and then consolidate the degt and assets into credit ratings. Standard & Poor’s only keeps them separate when the ownership is completely separate from councils.

Jonathan writes that councils could achieve what they want by going with another ratings agency, Fitch, because S&P is suggesting National’s approach of separation of assets without giving up council ownership would be pointless from a ratings point of view.

There's an argument that councils could loosen the borrow constraints simply to switching to another agency like Fitch, which does not necessarily consolidate all subsidiary debt up to the council that owns the crown-controlled organisations.

Fitch declines to comment for this article, while New Zealand is between governments, but S&P Global Ratings analyst Martin Foo is willing to discuss the different meanings and impacts of balance sheet separation.

He says part of the confusion is that the 'balance sheet separation' and 'financial separation' mean different things to different stakeholders.

"The former Labour government wanted its proposed water services entities to be sufficiently independent from their council owners that they could borrow heavily, in their own names, without impinging on council credit quality," he explains.

"Accountants may have their own definition of balance sheet separation. But from a credit rating perspective, our measurement of a council’s 'tax-supported debt' will include the debts of any related entities (including council-controlled organisations) where we see a very high likelihood that the council will provide support in case of need."

In other words, if they get in trouble, creditors expect the council will bail them out; water services are too big to be allowed to fail. As examples, S&P already consolidates council-owned holding companies like Christchurch City Holdings and WRC Holdings, and wholly-owned council-controlled organisations like New Plymouth Airport and Auckland's Watercare, in the financial metrics of their parent councils.

"Even in cases where we don’t consolidate related entities, we may still treat such entities as contingent liabilities of councils. And, if such contingent liabilities become large enough or their risk of materialisation becomes great enough, we may reflect this through a negative qualitative adjustment to our credit assessment."

So what’s the point? Really.

S&P’s Foo is quoted in a way that suggests the National approach may be pointless anyway (bolding mine):

On his initial reading of alternative proposals from Communities 4 Local Democracy and the Taxpayers’ Union, Foo says S&P might view a proposed water council-controlled organisation (whether owned by one or more councils) where there is a high degree of political control or ownership, alongside a high level of indebtedness, as weighing on the credit quality of its parent council or councils.

So structurally separating the organisation from the council doesn't give either a get-out-of-jail-free card; each may still be constrained by the other's borrowing. That's why, for instance, Watercare is warning that Auckland's water charges may have to double – because the parent council is so indebted that Watercare can't borrow to upgrade assets like the aged sewers that have collapsed in Freemans Bay and Parnell.

On the flipside, Foo says, even if a water organisation could theoretically be established in a way that restricts control, ownership, or financial support from parent councils, it’s unlikely to be able to borrow as cheaply as councils, and nor would it have access to borrowing from the Local Government Funding Agency. That's because the agency, by design, can lend only to local councils or to council organisations that are "explicitly backstopped" by local councils, in the form of a guarantee or uncalled capital.

"Together, these points highlight a fundamental tension at the heart of the reforms," Foo says. "An entity is unlikely to borrow on terms as competitive as the government (central or local) can, unless, well, it’s part of the government – or at least backstopped by the government. It is difficult to disentangle ownership of water-related assets from ownership of water-related debts."

The crux of the problem

So we’re right back where we started. Policitians and voters want to have their cake and eat it. They want low taxes, low debt and low-to-no water charges, but they want the water assets that give them clean water and allow more houses. They want to retain control, but not have to pay to build or maintain the assets. That’s all possible if you don’t repair your pipes as they age and your population doesn’t grow. This magical thinking works as long as there’s no stress on your infrastructure, the pipes don’t corrode, and you can push off the inevitable failures and leaks into the future. It also works if you’re comfortable with ever-rising land prices when the failure to invest in new infrastructure happens at the same time as the population is growing fast. Voters in local elections, who are overwhelmingly land owners, are fine with those spectacular rises in land prices, until the pipes start bursting. Then politicians and voters can blame previous politicians. Or someone else. Anyone else. Just not themselves.

The belief was that the magical thinking could be sustained by ‘taking the assets off balance sheets’, which implies someone else, the private sector, will pay for the assets by lending to the entities, and not expect either ownership rights, or a Government bailout, when things go wrong. But those bond investors have seen this movie before. They know that when it all goes wrong the Government or Councils will be forced by ratepayers voters to take back the assets, or will stop the higher charges needed to fund the debt. Either way, private investors are expected to take a hit on either the debt or the equity. They don’t want that, so they demand (through the ratings agencies) a government guarantee of some sort.

Hence, they are getting a Government-guaranteed bond that pays a higher interest rate than an actual vanilla Government bond. Their argument is there’s an element of uncertainty about the guarantee to justify the premium, but we all know that is a sort of strategic ambiguity that dissolves in a crisis. So why not just use a vanilla Government bond to start with? Because then that would increase net debt and mortgage rates in a way that median voters would not like.

An impossible trinity: low tax, low debt AND high population growth

And here we are at the same place Labour found itself. It wants high population growth with low Government debt and low taxes/charges. This does not compute. Choosing two of the three could make sense, including these combinations:

less than 0.5% population growth with taxes and charges less than 30% of GDP and net debt of less than 30% of GDP;

1.5-2% population growth with higher taxes and charges (eg 35%) and still low debt (eg less than 30% of GDP); or,

1.5-2% population growth with taxes/charges less than 30% of GDP, but net debt over 60% of GDP.

Instead, both National and Labour (and by implication the median voters who decide elections), have chosen and/or target an unsustainable trinity of:

high population growth of 1.5-2% for the last 20 years;

low public spending and low taxes (including no taxation of capital gains) of less than 30% of GDP for 30 years; and,

low public debt of less than 20% of gross debt until covid and less than 30% of net debt after covid.

How we keep kidding ourselves with this magical thinking

This is only sustainable if voters and politicians are happy to:

tolerate water quality that keeps making them sick and means they can’t swim at their beaches and rivers;

tolerate residential land prices that block another generation of renters from building stable and affordable futures for their own families through home ownership; and,

pretend there are no alternatives for renters and potential migrants to go to (ie Australia does not exist.)

At the moment politicians and voters are pretending that our population growth is going to go back to 0.5% next year, as soon as we’ve temporarily solved a labour shortage and the 200,000 temporary workers have gone home. The assumption is they don’t need a place to live or a motorway to drive in or a hospital to use until they are residents. It is assumed temporary workers can live…somewhere…and that they won’t get sick or need welfare. We discovered what that meant during covid. Unemployed temporary migrants literally became (and often still are) homeless and literally ran out of food.

We can’t have it all. We have to choose.

I would choose a publicly agreed and planned-for high population growth rate of 2% per annum, which allows for recruitment of migrant workers as residents, and chooses to use higher congestion/water/parking/emissions charges and taxes to both manage demand and service the higher debt needed to sustain the infrastructure. That would mean higher mortgage rates, higher vanilla public debt levels and lower land values, especially if one of the higher debt elements was a capital gains or residential land tax.

It would mean a Government and tax level of at least 35% of GDP and net public debt of up to 60% of GDP, including some form of wealth, capital gains or residential land tax. It would mean lower land values, more affordable rents and first homes, and meeting our emissions reduction targets.

That would also mean 20 million people living in Aotearoa by 2100. It would mean five million on the Auckland isthmus and North Shore, and a further 10 million in South Auckland and the Waikato.

That appears shocking and unbelievable to most right now, but it’s actually where we’re headed with the population growth rates we’re currently pursuing in an accidentally-on-purpose way. It’s also a level of growth we’ll have little choice but to accept because 100 million wealthy families in North and South Asia will want to live in Aotearoa as a climate haven.

At the moment we are all kidding ourselves that we can magically have it all, or that we can pretend we can until it is someone else’s responsibility to deal with it. It is the ultimate in irresponsibility, selfishness and self-delusion. It’s quite human, but it’s not sustainable for humans and the planet in the long run.

So it turns out finger-wagging doesn’t dissolve duopolies…

The Commerce Commission’s first suggestion to the Labour Government for solving our supermarket duopoly problem was a structural separation or breakup whereby the duopoly was effectively legislated and regulated out of existence to create a third player out of the bits carved off the big two. After a vigorous lobbying campaign, that was watered down in the final version of the Commerce Commission’s Market Study recommendations into a code of conduct and a stern talking to about being nicer to competitors and suppliers.

The most substantial outcome of the inquiry was Foodstuffs and Countdown/Woolworths volunteering to stop applying covenants on their land titles and leases blocking new competition, which was so egregiously anti-competitive that stopping would be the least they could do. The rest of the formal response was the creation of a Grocery Commission to monitor the duopoly behaviour and apply moral suasion through stern tellings off. Essentially, asking the duopoly to stop being duopolistic.

Surprise, surprise, but the finger wagging didn’t work. On the same day Supie was put into administration, the first Grocery Commissioner Pierre van Heerden released his ‘Top 3 on his ‘Fix-it’ list,’ including speaking to suppliers at the Food and Grocery Council’s annual conference in Sydney next week with a “simple message” (bolding mine):

“…that to be a trusted and favourite brand in the grocery sector, they have a responsibility to co-operate with the grocery regime and play fair in the system. Consumers expect this of them, as their brands are built on consumer trust.”

“RGRs (Regulated Grocery Retailers) are now required to sell wholesale groceries to retail competitors, enabling alternative retailers to access more products at better prices, and better compete in the sector – whether that be using wholesalers or purchasing direct from the supplier.”

“We are aware that a number of influential suppliers appear to be opting out of the RGRs’ wholesale offers and insisting on supplying direct to smaller retailers but at much higher prices, which is having a negative impact on retail competition.” .

Really? A regulator asked nicely and was ignored? I’m shocked! Shocked.

We found out yesterday who the scallywags were.

Mr Muscle and Twix outmuscle the finger wagger

Supie founder Sarah Balle told Newsroom’s Jonathan Milne that Fonterra, Tatua, SC Johnson (Raid, Mr Muscle and Pledge) and Mars (Whiskas, Twix and Dolmio1) had opted out of the system.

Balle also said it was nigh-on impossible for independent retailers to get new direct deals with these companies – meaning they could neither source these key consumer brands via the supermarket wholesale mechanism, nor directly.

She said opening up wholesale via the supermarkets sounded like a good idea but had been another failure because major suppliers like Fonterra, one of New Zealand’s biggest companies, had opted out. "It's disappointing, given they should be doing what they can to help Kiwis. Helping the duopoly doesn’t count in my eyes!"

Van Heerden, who has just taken up the new role of Grocery commissioner at the Commerce Commission, said he had been talking with Balle about Supie's difficulties with suppliers.

"One of my points today is making sure that suppliers do their part, that they don't opt out of the wholesale supply network in order to supply their product direct at a higher price."

This is how New Zealand works:

powerful interests take the piss;

consumers complain and eventually politicians join in;

a study is launched and eventually some sort of voluntary persuasive approach is taken;

powerful interests take the piss in the quietest way possible, while using their resources to lobby, dissemble, distract, deny, distract and destroy any substantive action;

those interests operate a series of revolving doors to employ and contract politicians, political operatives and bureaucrats;

the public gets so frustrated that legislation is tabled and the interests are able to water down the measures taken through the Parliamentary process; then,

they hope to delay, deny, distract and dissemble long enough for ‘their’ side to get in and do the same all over again.

We’ve seen it time and again in fuel retailing, electricity, banking, insurance, building materials and groceries.

Incoming Finance Minister Nicola Willis said yesterday she also wanted a third competitor, but did not say how that would be facilitated by the Government, given it would require regulatory or commercial intervention, legislation, funding and commitment. The last National Government avoided taking direct or coercive action against monopolies and anti-competitive behaviour. Labour tried to toughen the environment for those with dominant market power, but was eventually blunted and co-opted too. It could be argued it paid for that inaction on monopoly power with its own life when the monopolists took advantage of an inflationary environment to force through even higher profit margins, which extended the inflationary surge into an election year.

The strategy of deny, delay, distract, dissemble and divide has worked.

Our climate liability is growing, but isn’t being accounted for

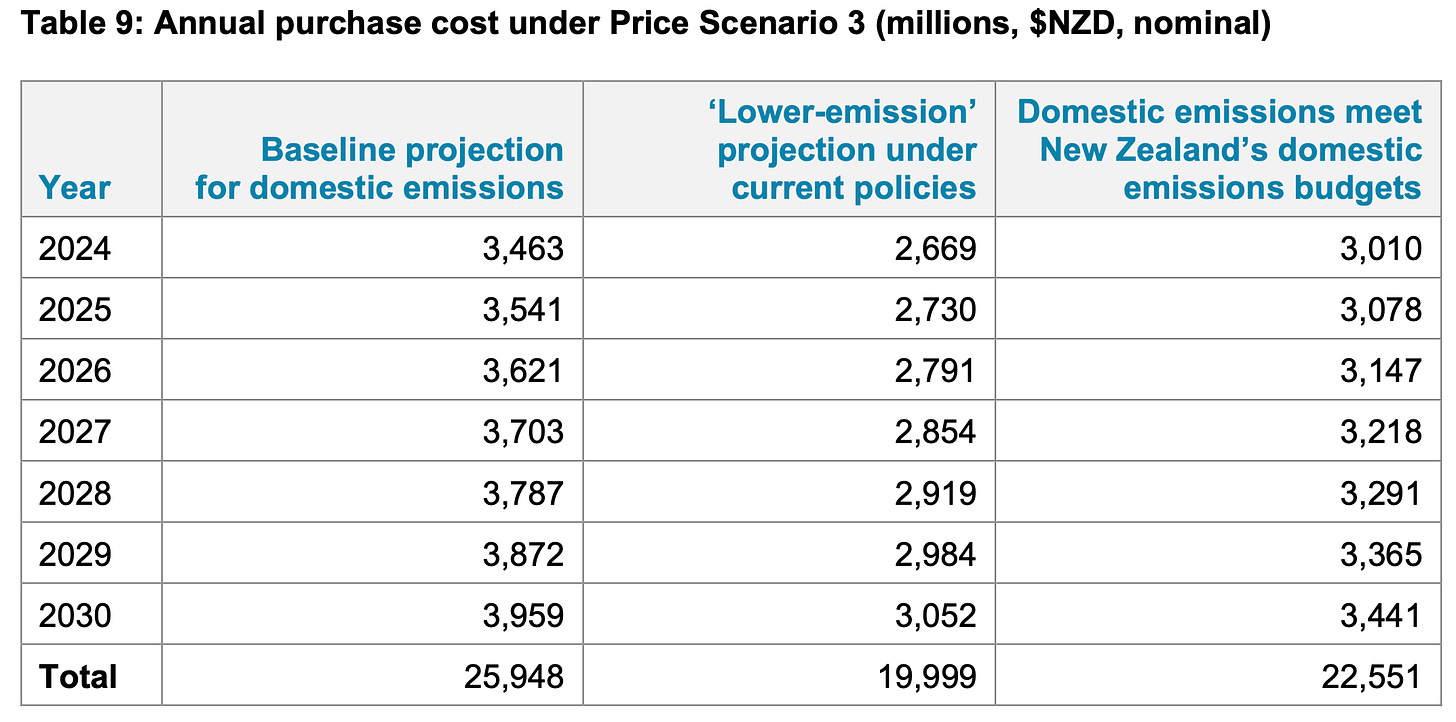

A Treasury analysis of the potential costs of the Crown having to buy emissions credits to meet its Paris agreement commitments was released in September and shows the cost to taxpayers could blow out to $25.948 billion by 2030, if as expected with current policies, there is a shortfall of 114.12 megatonnes of emissions reductions at a price of up to NZ$243/tonne.

This is not included in the Crown Accounts as a contingent liability. If it was, a Government would be obliged to try to reduce it, or have to explain to taxpayers why they’re spending more on emissions credits overseas than it spends on health in a year.

The other option would be to renege on the Paris agreement, which ACT has advocated, and then see New Zealand’s FTA with Europe cancelled arbitrarily.

Chart of the day

The one where businesses see the economy as better under National

Cartoon of the day

Devastating

Ka kite ano

Bernard

PS: My apologies for the lateness and volume today. I hope it’s worth it. I took a bit more time to lay out the impossible trinity.

I’m sure Mars make Dolmio, Twix and Whiskas from different ingredients in different factories. Well, I’m hopeful at least. Reasonably confident.

Share this post