TLDR & TLDL: Here are the five things I think mattered or where my view changed this week:

My view on when our borders will open properly beyond Australia shifted to late 2022.

We saw our Government talk publicly for the first time about the need for our exporters to diversify away from China.

Our Reserve Bank took the lead in forecasting rate hikes next year, although it also sees the current inflation surge as temporary.

Climate activists showed the most effective place for real action is the boardroom and courtroom, not in parliaments or global summits.

Dominic Cummings exposed to all, if there was any doubt, that Boris Johnson is an awful Prime Minister and his bad leadership may have cost up to 30,000 British lives.

Don’t plan to travel beyond Australia until at least late 2022

Sorry, and I don’t love it either, but I came to the view this week that our borders won’t open beyond Australia until late next year. It’s all about Australia.

We can’t really open until they do because most of our visitors either come directly from Australia or bounce through Australia to here. The Australian Federal Treasury forecast in its Budget a couple of weeks ago that Australia’s borders won’t reopen until the second half of next year.

As of Thursday last week, just 1.9% of Australians were fully vaccinated and 13.5% had had one dose, and Australia is relying mostly at this point on the AstraZeneca vaccine it’s making in Melbourne, which is not as effective or as popular as the Pfizer vaccine we’re using. Australia has a multi-vaccine strategy managed independently by each of the states. It’s messy. Just think multiple-DHB-style messy on steroids. That makes getting to herd immunity tougher than a simple Pfizer-only strategy.

New Zealand is 3.9% fully vaccinated and 7.5% have had one dose. We may have started slower, but we’re more likely to come flying down the home straight to herd immunity, which our cabinet sees at around 70% and is likely to be a pre-condition for full opening. A Ministry of Health survey here in April found 77% of New Zealanders are likely to get the vaccine, up 8% from March. The survey showed Māori willingness to be vaccinated at 71%, up from 64%; and Pasifika at 79% up from 59%.

The story is different in Australia, in part because of the focus on AstraZeneca’s high profile (but low incidence) problems with blood clots. Those problems forced Australia to delay its vaccine rollout and recommend Pfizer for under 50s. A Resolve Strategic poll for the Sydney Morning Herald published last week found 15% of Australians said they were “not at all likely” and 14% “not very likely” to be vaccinated in the months ahead. Australia’s vaccine hesitancy rate is now significantly higher than ours.

‘Diversify away from China in case there’s a storm’

Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta started telling exporters publicly this week to diversify away from China in case New Zealand gets an Australian-style treatment on trade by China’s ‘wolf warrior’ leaders. These messages have been going out privately from the top tier of cabinet for months.

Our relations with China have cooled, and justifiably in my view and increasingly in the view of most of our politicians. Former Prime Minister John Key, who lamented the deterioration at a China business conference in Auckland this month, is an exception. China under President Xi Jinping is a dangerous bully, a cyber-attacker and thief, and profoundly undemocratic force in global politics and within its own borders.

“We cannot ignore, obviously, what’s happening in Australia with their relationship with China. And if they are close to an eye of the storm or in the eye of the storm, we’ve got to legitimately ask ourselves – it may only be a matter of time before the storm gets closer to us. The signal I’m sending to exporters is that they need to think about diversification in this context – Covid-19, broadening relationships across our region, and the buffering aspects of if something significant happened with China. Would they be able to withstand the impact.” Nanaia Mahuta in an interview with the Guardian Australia’s Tess McClure.

The support for this tougher stance is across the Parliamentary spectrum, with a few exceptions. The decision to remove the word ‘genocide’ from a Parliamentary motion earlier this month condemning China’s mass-imprisonment-and-enslavement of the Uighur minority in Xinxiang was the last gasp of appeasement.

AAP reported yesterday a range of MPs plan to join the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC), which currently includes Labour’s Louisa Wall and National’s Simon O’Connor.

"We continue to call for an independent international investigation. The Uighur in Xinjiang are experiencing ... organ harvesting, measures to prevent women giving birth and the forcible transfer of Uighur children out of their community."

Louisa Wall in an interview with AAP’s Ben McKay.

Australia's 60 Minutes is set to air an item this weekend that takes a very hard line that New Zealand is appeasing China and is ‘soft’ on China. The piece is headlined: “New Xi-land.” I don’t think that’s true any more. It used to be.

It wasn’t that long ago both NZ’s major political parties included Chinese-born list MPs with strong connections to China’s Communist Party and there were regular and friendly meetings between NZ and Chinese ministers and officials. NZ’s Free Trade Agreement with China was the rising giant’s first with a developed economy and NZ had helped the People’s Republic join the World Trade Organisation.

Then-Prime Minister John Key was glowing in his praise of China’s development and actively sought opportunities for Chinese investment in New Zealand from 2008 to 2016, and vice-versa. Then-Prime Minister Bill English hosted a visit by China’s head of state Li Keqiang to NZ as recently as March 2017, where they signed a memorandum of understanding to cooperate on China’s monstrous yet nebulous Belt and Road Initiative to improve road, rail, telecommunications and other links between China and….everywhere.

Fast forward four years and NZ and China are now eyeing each other much more warily. NZ has criticised China’s human rights performance publicly and regularly in the last year, along with Australia, the UK, Canada and America in various ways and venues. This would have been unthinkable in 2017.

That wariness is now a bipartisan view and reflects the debate and reporting seen over the last four years, including around National list MP’s Jian Yang’s past, the Huawei 5G stoush and China’s attempts to bully Australia on trade access. It also is a reaction to China’s growing aggression and influence over its diaspora and trading partners in their countries, through a variety of mechanisms, particularly under China’s President Xi Jinping, who was not in charge when NZ signed its FTA with China in 2008.

This week that was reinforced by reporting by Politik (paywalled) that Jian Yang and Labour List MP Raymond Huo were quietly shuffled out of Parliament in a deal done behind closed doors just before last year’s election by the Labour and National Chiefs of Staff after intelligence agency briefings.

I helped organise the joint investigation by Newsroom and the FT in September 2017 that exposed the National List MP’s background. This toughening of New Zealand’s view is long, long overdue, but it is finally here. Mahuta has been deft in steering our stance towards this point without upsetting the apple cart too much.

Australia has taken a much louder bull-in-a-China-shop approach, but can afford to because China has no choice and a huge need to buy Australia’s iron ore. China may have restricted imports of Australian wine, sugar, barley, wheat, coal, logs and fish, but has not restricted iron ore imports. Part of the story here is that two huge mine dam washouts in Brazil have given Australia a sort of monopoly, and now iron ore prices are near record highs. Taxes on these exports have actually driven Australia’s Federal Budget into surplus in the last two months.

When the activists put on suits and win

This week Shell, Chevron and Exxon were all hammered in courts and in share proxy battles by climate change campaigners. The tide is turning hard in favour of regulators, financiers, sovereign wealth funds, activists and courts using whatever tools they have to force Big Oil companies and others to reduce emissions.

A Dutch court ruled Shell would have to shrink its emissions by 45% from 2019 levels by 2030 to comply with human rights law. (CNBC) Meanwhile in America, a climate activist hedge fund, Engine No 1, successful managed a shareholders’ revolt to put two members onto the board of Exxon. (Reuters) Shareholders on Wednesday voted in favor of a proposal to cut emissions generated by the use of the company's products, a move that underscores growing investor push at energy companies to reduce their carbon footprint. Chevron shareholders voted 61% in favor of a proposal to cut so-called "Scope 3" emissions. (Reuters)

Yesterday was the deadline here too for new climate exposure reporting standards for NZ’s 200 biggest banks, insurers, money managers and listed issuers of stocks and bonds. Failure to comply with the Financial Sector (Climate-related Disclosure and Other Matters) Amendment Bill could hit company boards with fines of up to $500,000 and five years in jail. Don’t expect to be able to get insurance for or be able to borrow much against a property with sea level, flooding or bush fire risk in the years to come.

I think it will be the banks, investors and insurers that drive real climate action by carbon emitters, rather than politicians and Governments doing a lot of talking at summits and declaring climate emergencies. I’m watching most closely which of the massive global wealth funds are pulling out of climate policy laggards, and how banking and insurance regulators force banks and insurers to price firms’ climate risks through emissions disclosure and capital requirement rules.

Wage inflation is the trigger to watch

This week we saw central banks all over the world and here have to push back against investors and politicians worried that the current surge in prices because of Covid-related supply disruptions and a rebound in economic activity. The inflationistas want central banks to raise interest rates to avoid overheating the economy and creating runaway inflation.

Until now, central banks overseas have held their nerve and told markets they see the inflation as transitory and they want to see the ‘whites of the eyes’ of inflation well above 2% before they pull the trigger. They don’t want to make the same mistakes made from 2009 to 2016 when they all acted too early and had to reverse little rate hikes, leading to a decade of inflation below 2% level.

The US Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia have gone as far as saying they’re now targeting average inflation over the longer run and want a decade of inflation over that 2% level to compensate for the decade under 2%. Our Reserve Bank hasn’t gone that far, but is also pursuing a ‘least regrets’ policy of keeping policy loose until it’s clear capacity is all used up and the economy is really generating inflation.

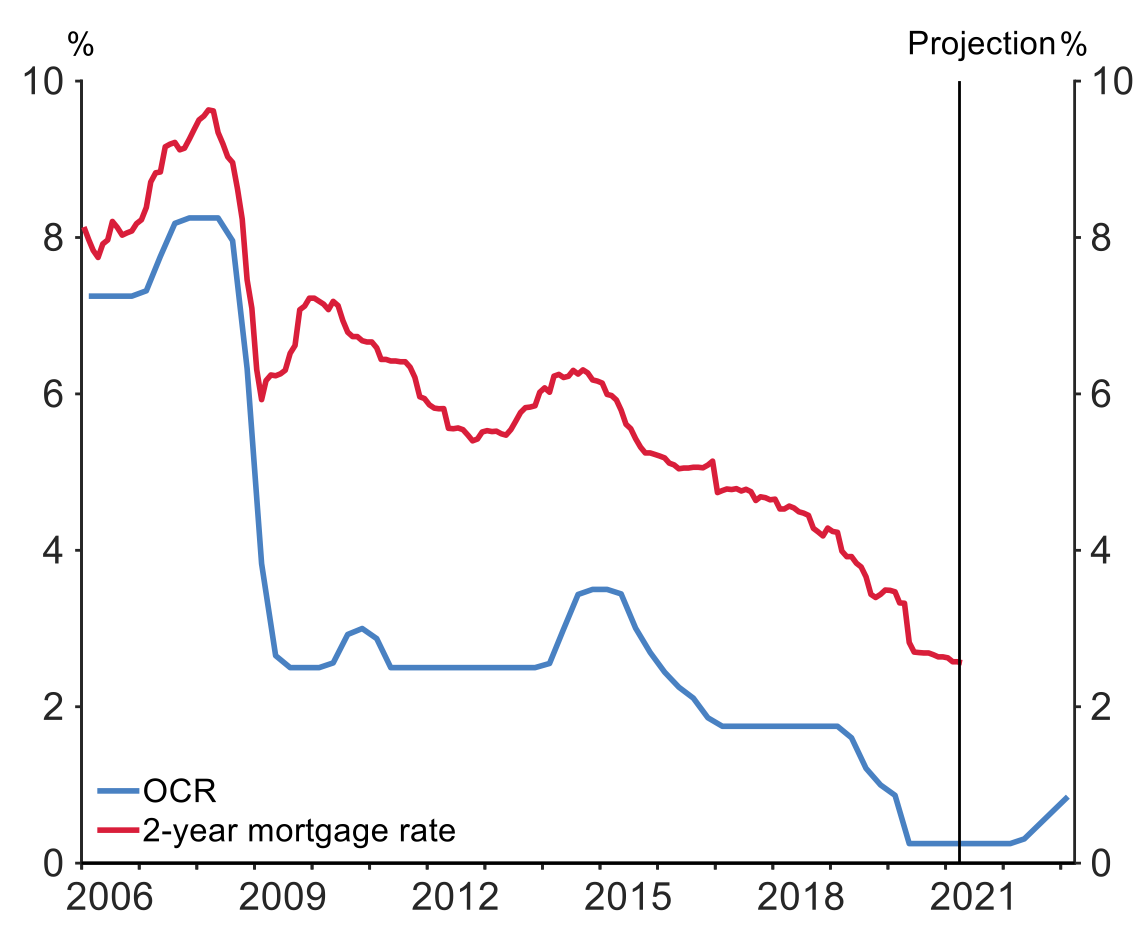

In my view, our Reserve Bank should do what the Fed and RBA are doing: hold its nerve and wait until it sees inflation over 2% for a considerable period. It needs to rev the economy hard to blow the cobwebs out of the engine and get it nice and hot so we can get ‘rev counter’ of interest rates sustainably up to more normal levels sooner, rather than later. We have had an OCR below 3.5% for 12 years when the Reserve Bank has seen the ‘neutral’ rate above that for all that period. The risk is investors start believing a 0.25% OCR is normal and ‘bake in’ that level to their investment and income assumptions.

There are plenty of nervous nellies calling for rate hikes now. I have a different view, which is that structural deflation from the appification of the services sector and very weak labour power will lock in these unnaturally low levels of inflation and interest rates, Japanese-style, without a real burst of hotter-than-normal activity driven by fiscal and monetary policy. We have to break out of this trap with the foot to the floor for longer.

This week the Reserve Bank surprised markets with a more hawkish tilt to its interest rate forecasts than most expected, but Governor Adrian Orr also cautioned traders who had just pushed the currency and wholesale interest rates up on Wednesday afternoon that the bank’s projections were no sure thing.

“We are talking about the second half of next year. Who knows where we will be by then,” Orr told the bank’s May Monetary Policy Statement news conference.

Earlier, the bank released projections it would start increasing the Official Cash Rate in mid-2022 and raise it to around 1.75% over the following two years. That would make NZ’s central bank one of the first in the developed world to hike rates since the Covid crisis.

Economists said the steepness of the forecast rise was more than expected and they also noted the removal of the language seen in previous monetary policy committee decisions around the potential for negative interest rates and or the possible need for more easing. Interestingly, Orr effectively reinserted the negative rate option by talking about to the Finance and Expenditure select committee the next day.

But will the Reserve Bank actually be able to deliver those hikes? There have been plenty of false starts before and those who fixed their mortgages for five or more years in expectations of a very fast and big rise in interest rates have been burnt.

In my view, the Reserve Bank was right to caution about the temporary nature of the inflation spike going through over the next year as supply chains normalise and the global economy has a burst of post-Covid recovery - because the basic and deep structural headwinds for inflation are still there in spades. The appification of the services sectors of most economies has only just started, and the wage-hiking power of workers remains weak as employers keep contracting out, importing lower wages and union densities remain very low.

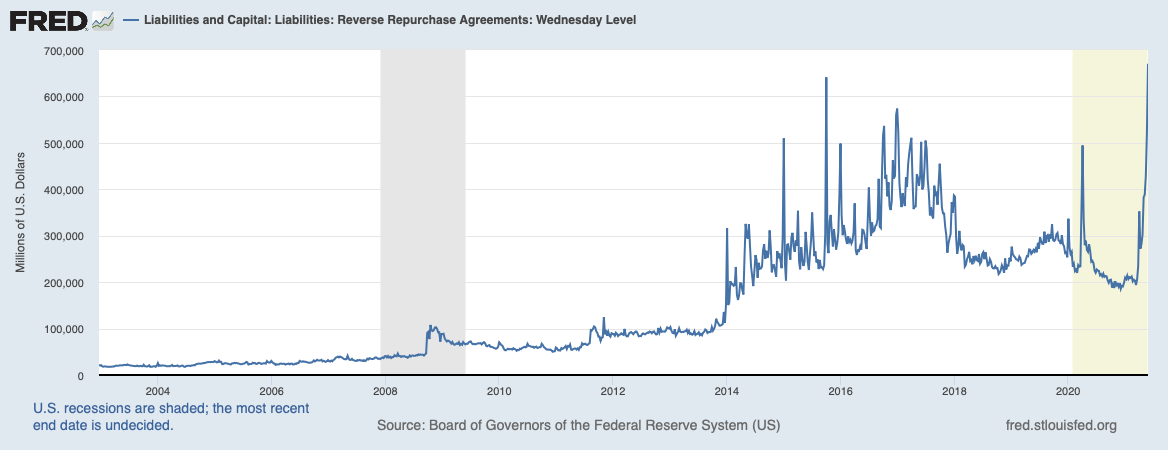

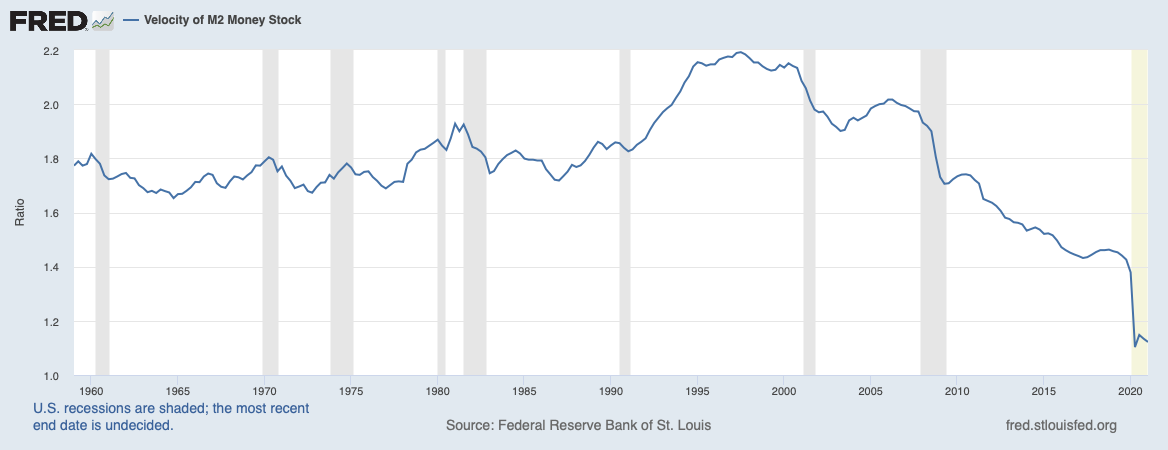

Many inflationistas argue ‘this time is different’ and that the US$10t of fresh cash printed to buy bonds from banks and pension funds will eventually start circulating among real investors and consumers, boosting real prices. That remains an open question and the history over the last 20 years is dominated by a slowing circulation of the global money supply as risk-averse and older investors stash away ever-more cash and wealth in unproductive bank accounts and stores of value, rather than in productive assets or in spending. The first priority of very, very rich investors is always to preserve wealth, and the scale of the wealth now concentrated among the wealthiest is impossible to spend quickly or widely. The three charts below show how much wealthier they’ve gotten, how so much money is now parked back in the US Federal Reserve, and how slowly all the freshly-printed US cash circulates as it’s stashed away rather than invested or spent on goods and services.

It does mean, however, that art dealers, vintage car sales people and crypto-currency speculators are seeing plenty of asset price inflation.

In my view, the Reserve Bank should be adopting the ‘average’ inflation targeting approach now being used by the US Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia, which say they want inflation to run ‘hot’ and above their 2% midpoint target for some time to offset the decade of inflation below 2% seen since the GFC. The Fed and the RBA want to see the ‘whites of the eyes’ of inflation before they pull their triggers. That means they have been reluctant to project rate hikes yet and have been comfortable allowing their economies to ‘overheat’ slightly to get inflation up substantially and reach ‘exit velocity’ so they can truly normalise interest rates sooner.

The Reserve Bank’s caution is evident in its inflation forecasts, which only barely get above the 2% midpoint by the end of the forecast period. If it was ‘redlining’ the economy to reach exit velocity, its forecasts would see inflation closer to three percent or higher, and that would be just fine. That would also mean the Reserve Bank would have left its OCR track flat, or even suggested cuts. But, for now, the Reserve Bank is taking an overly cautious approach on inflation, in my view. Another failure to exit the 22 risks further embedding expectations of very low interest rates forever, and undermines the only thing any Reserve Bank needs: public confidence that they are able to forecast accurately and keep inflation around 2% for the long run. It’s been 10 years now that inflation has been worryingly under 2%.

But the key question is how will we know that inflation is really taking off. So far we’ve seen commodity prices surge and many ‘intermediate’ goods prices rise that manufacturers are paying. Some have been passed on to consumer prices. The real test is whether all the reported labour and skilled shortages turn into wage increases. So far they haven’t — not overseas and not here.

US President Joe Biden is actively calling for those wage increases, almost goading the markets and Republicans into increasing wages if they really believe in free markets and the primacy of capitalism.

“You can’t reboot a global economy like flipping on a light switch. There’s gonna be ups and downs in jobs and economic reports. There’s going to be supply chain issues and price distortion on the way back to stable, steady growth. Rising wages aren’t a bug, they are a feature . . . Instead of workers competing with each other for jobs that are scarce, we want employers to compete with each other to attract workers. Corporate profits are the highest they’ve been in decades, and workers’ pay is the lowest it’s been in 70 years. We have more than ample room to raise workers’ pay without raising customer prices.” Biden talking overnight as he launched a US$6t Budget plan, including US$4t of infrastructure spending and US$2t of stimulus.

Former US Federal Reserve Chair and now-Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen is also holding her nerve and pushing back.

“The recent inflation we have seen will be temporary, it’s not something that’s endemic.” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen speaking this week at a Congressional hearing.

We’ll all know if the inflationistas are right or the Keynesians are right when (or if) wage inflation starts to rise. My view is the downward pressure of low-to-falling unionisation rates, the globalisation of services through the app economy and the continuing shift to contract out and parcel up work.

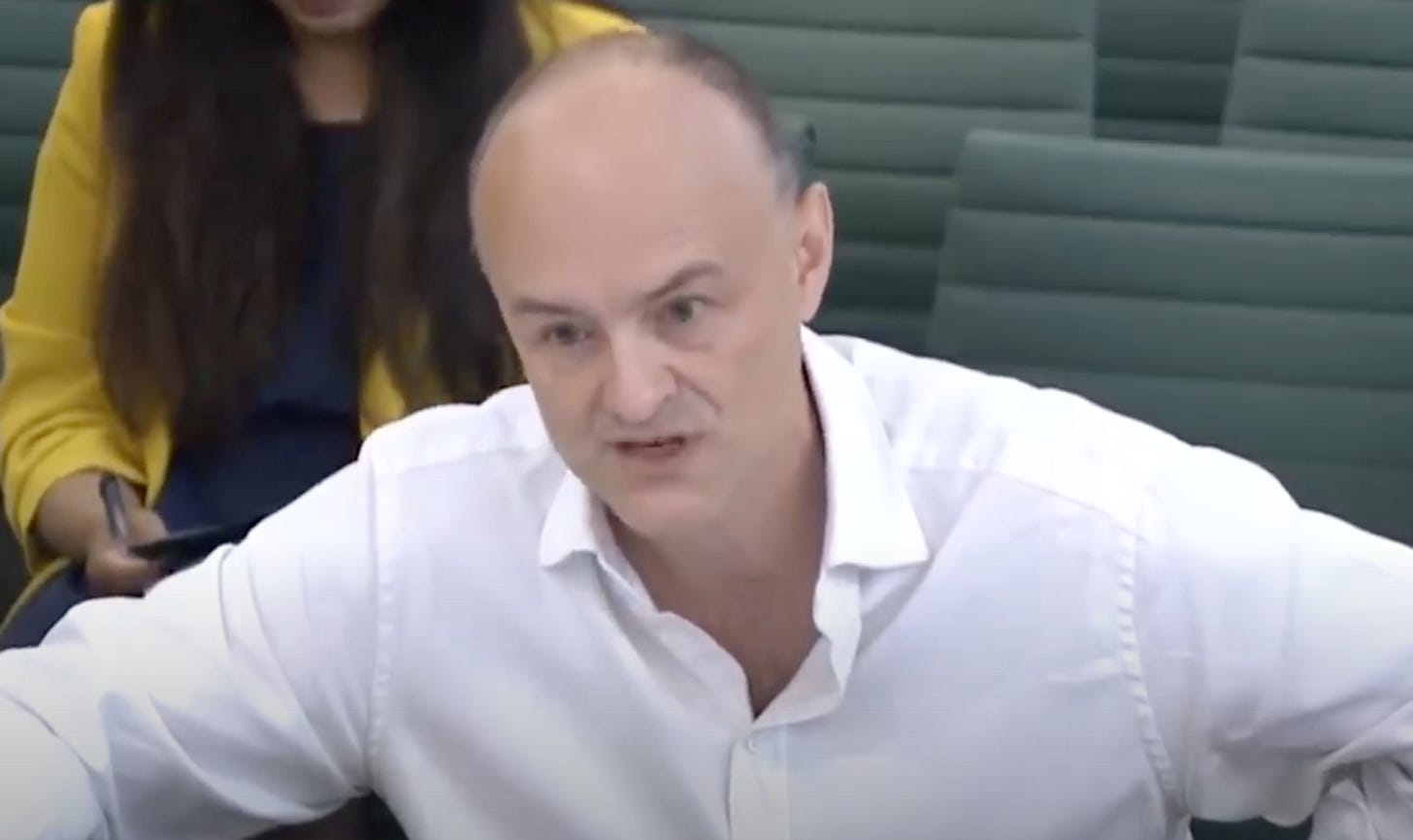

Bad leadership costs lives

The big set piece in the world of politicos this week as Dominic Cummings’ appearance before a Parliamentary select committee in London. He savaged Boris Johnson and reinforced just how awful the British Prime Minister’s leadership has been and how many lives it may have cost.

This quote from Cummings is the best in a cavalcade of pithy and cutting one-liners:

“Nobody could find a way around the problem of the prime minister, just like a shopping trolley, smashing from one side of the aisle to the other.”

And Britain’s pandemic is far from over. Britain’s case numbers increased this week despite having a one-dose vaccination rate of 73% and a two-dose rate of 45%. One in 10 hospital admissions for Covid in the UK this week were for fully-vaccinated people. Over 75% of cases in the UK are now of the Indian variant. Germany and France stopped unquarantined entry of Britons this week because of fears about the Indian variant (the B.1617.2 strain).

The importance of tightly controlled borders and lockdowns was hammered home this week when Imperial College London’s now-renowned Covid modeller, Neil Ferguson, said Britain’s decision to delay its lockdown for a week around March 13 last year is likely to have cost up to 30,000 lives. He was commenting after Cummings accused the PM of incompetence that cost up tens of thousands of lives. (Yahoo)

“I think that’s unarguable. I mean the epidemic was doubling every three to four days in weeks 13 to 23 March, and so had we moved the interventions back a week we would have curtailed that and saved many lives.” Imperial College London Professor Neil Ferguson.

Ka kite ano

Bernard