TL;DR: My top six news items of note on the morning of Tuesday, April 2 include:

A review of council borrowing has found central Government-driven debt limits are strangling big councils’ ability to borrow to build enough infrastructure for growth, although some councils are further tightening the reins with even lower self-imposed limits and by over-playing fears of credit rating downgrades (see more detail and analysis below and in the podcast above, which includes my interview with Te Waihanga-Infrastructure Commission Director of Economics Peter Nunns1);

Christopher Luxon has announced a new 97-day action plan to succeed his 100-day plan, saying his Government will keep using Parliamentary urgency to enact it;

MSD and Work & Income have resumed social housing tenancy reviews that were suspended in 2018 and during Covid, starting by looking at pushing 400 longer-term tenants into private rentals; Beehive Work & Income

The Warehouse’s CEO has said he wants the Government to step in to control wholesale grocery prices because it says the voluntary regime isn’t taming the duopoly; The Post-$$$

The Government has announced it had halted plans for a Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary that were first announced by John Key in a 2015 speech about sustainability to the UN General Assembly; and,

ANZ has changed its ‘rental shading’ rules for residential property investors in a way that allows them to borrow more to buy an existing property, and increase their competitive power to outbid first-home buyers. OneRoof

Just briefly elsewhere in Aotearoa-NZ’s political economy at 8 am:

Tory Whanau asks for law change to quickly remove heritage status The Post-$$$

Christchurch Council in secret talks to bail out A&P show The Press-$$$

A third of hospital buildings are beyond their design life, Reti told NZ Herald-$$$

(Paying subscribers can see more detail and analysis below the paywall and in the podcast above. We’ll open it up for public reading, listening and sharing if they give permission by getting over 100 likes.)

Debt rules strangling big councils’ infrastructure hopes*

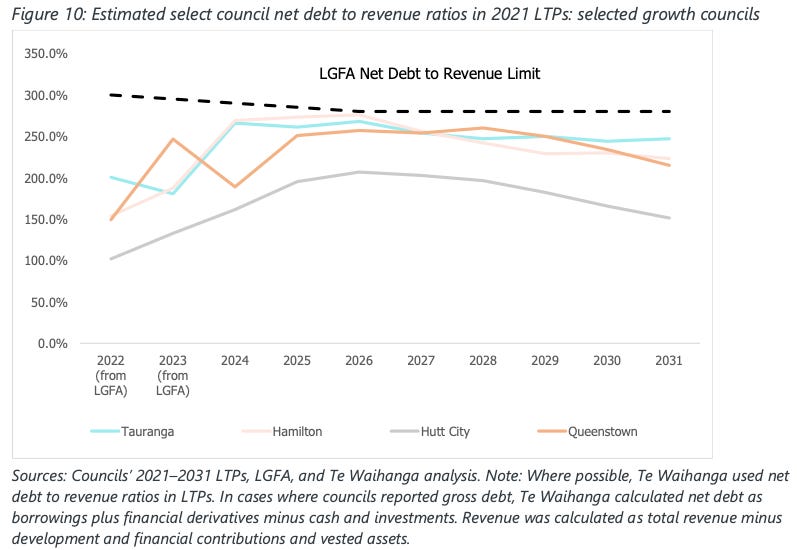

A review of council borrowing by Te Waihanga-NZ Infrastructure Commission has found Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA) rules on debt limits and the way councils interpret them is restricting high growth councils such as Auckland, Wellington, Tauranga, Christchurch and Queenstown from borrowing enough to fill existing infrastructure deficits, let alone cope with future population growth.

The review suggested councils were unnecessarily afraid of borrowing extra because the cost of credit rating downgrades was much lower than many thought, and that the debt limits often described as immovable-restrictions-from-on-high could be surmounted. It concluded that councils were more worried about perceptions of fiscal irresponsibility than they should be, and that LGFA should look at raising its debt limits for high-growth councils.

The review suggested councils could:

leave LGFA to borrow outside these debt-to-revenue limits and take a manageable hit to their credit ratings and borrowing costs;

for some, increase the self-imposed debt limits that are currently set below the official ones;

shift revenue-producing assets such as water infrastructure out of political control into Council Controlled Organisations that can borrow more in their own right;

generate higher revenues to increase debt-servicing capacity through the likes of value-capture rates, congestion charges; and,

creating special targeted rates to support the creation of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) to borrow separately from Councils.

It also said LGFA could allow higher debt-to-revenue limits for larger and higher-growth councils, removing the current one-size-fits-all policy of 280% for councils with credit ratings and 170% for those without credit ratings.

In my view, the most interesting elements of the review that make up the asterix in the headline were:

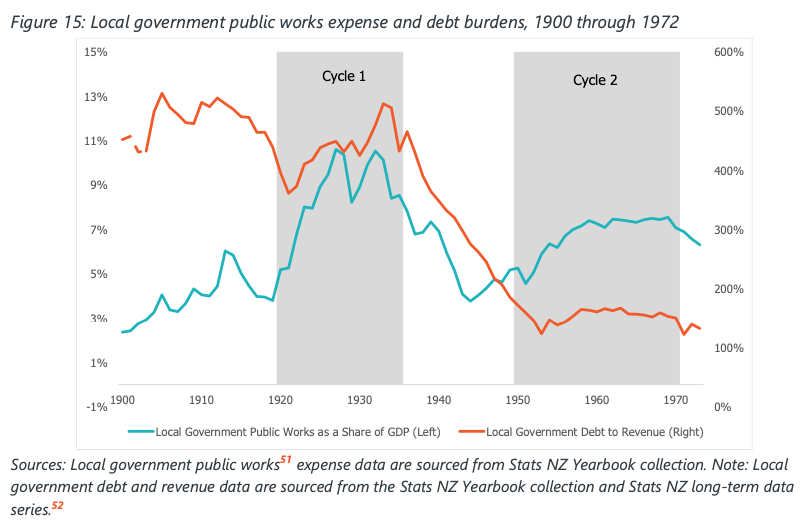

a finding that councils supported much higher debt burdens before the 1950s and they kept their debt levels very low between local government reforms in 1989 and the beginning of higher infrastructure spending in 2008 (see chart below);

that only five of the 72 councils have debt over 150% of revenues and that some had set lower limits internally than the LGFA ones (see chart below);

that Auckland Council estimates a one-notch downgrade in its current AA credit rating would increase borrowing costs by just five to 10 basis points, which would increase the council’s interest bill by less than $2 million per year, which represents a hit of less than 0.03% of its operating budget;

Council net interest costs as a share of revenues, which LGFA limits at 20%, averaged 3% across rated councils in 2022, with the high debt councils averaging in the 6% range;

The median council with a credit rating had a debt-to-revenue ratio of 120% at the end of 2023, and the median council without a rating had a ratio of 41%, vs the LGFA limits of 280% and 170%; and,

that Crown Infrastructure Partners (CIP) estimates (pages 31, 32) that available financing through SPVs would only represent just one-fifth ($1.5 billion) of the current LGFA borrowing of around $7 billion per year and just 1.5% of the infrastructure investment seen needed over the next 30 yerars. CIP BIM

So what?

Aotearoa-NZ can’t solve its housing affordability, climate change and poverty crises without new and renovated housing, public transport and water infrastructure.

Nothing happens unless councils agree to invest in pipes, buses, trains, tracks and roads, given they’re responsible for between 50-100% the capital and maintenance spending respectively for these items alone. The Government has to agree to fund around 50% of public transport and roads, plus 100% of health and education.

So the appetite and ability to build and then properly maintain this infrastructure depends on the borrowing capacity and attitudes to debt of the central Government and councils, given financing long-term assets with debt is the fairest and cheapest way to fund them. There is now a $100 billion infrastructure and varying estimates put the spending needs over the next 30 years at $100 billion to $200 billion.

So why don’t the central Government and councils borrow to make up for past under-investment and to ‘pay it forward’ for future generations to use and pay for? What outside forces or past decisions are stopping the Government and councils from getting on with it? It is not because there is already too much debt or global and local private investors won’t lend to New Zealand governments. The Crown’s debt is less than a third of problematic levels and council debt is less than a fourth what it was when councils were paying to build water and power networks in the first 50 years of the 20th century

Is it because rules put in place by the Treasury-run LGFA are unnecessarily strict? This review suggests that’s part of the problem, but in the end concludes the problem is mostly political and driven by the perceptions of ministers, officials, mayors and councillors that they’ll be punished for being ‘fiscally reckless.’ This review argues there are ways within the existing rules to borrow more, or the rules could be changed, and that the ‘fiscally reckless’ fear is unjustified.

Here’s the review summarised in its own words (bolding mine):

Councils are likely to have debt capacity in excess of LGFA limits because the fundamentals of council debt are strong. All councils currently have low debt

servicing costs. Even if it were downgraded, council debt would still be considered of high quality to domestic and international markets, especially relative to other private infrastructure providers.Councils are not legislatively prevented from leaving LGFA and taking on higher debt ratios. However, leaving would require them to refinance their entire stock of existing LGFA debt, which could be administratively costly. There is also the fear of a credit downgrade and higher borrowing costs. However, the financial cost of a modest credit downgrade is unlikely to prevent councils from servicing their debt.

Rather, the main cost appears to be reputational. Leaving the LGFA may be judged as fiscally reckless.

Further, while council debt burdens have been growing of late, history also tells us that they’ve been significantly more indebted in the past, as measured by their debt-to-revenue ratios. In the 40 years prior to the Second World War, local government sustained debt burdens that were four to five times greater than they are today. Te Waihanga-NZ Infrastructure Commission review of council borrowing published on Thursday.

We’re strangling NZ’s future to inflate tax-free capital gains today

In my view, the review has reinforced that our infrastructure deficits were and are political choices made by Governments of both flavours for the last 40 years aimed at reducing taxes, limiting rates increases and reducing mortgage rates to enrich existing homeowners at the expense of renters and future generations.

The limits are not financial ones set by the bond market gods. They are set by politicians elected by median general election voters and most council voters2 who, conciously or subconciously, understand maintaining the status quo is in their interests, even if it is not in the interests of their children and grandchildren.

How does this work? Lower rates increases and income tax cuts maximise disposable income which can then be leveraged to buy more residential land. Lower Government and council investment limits the supply of residential land competing with voters’ own land, which ensures leveraged and tax-free land value increases are maximised. Lower investment also limits Government and council debt, which, all other things being equal, ensures mortgage rates are lower than they otherwise would be.

The perfect recipe to maximise leveraged tax-free capital gains on residential land is:

low income taxes and no capital gains tax or wealth tax;

low public and council debt to ensure low mortgage rates and the lowest possible rates increases;

high population growth without matching investment in infrastructure; and,

imposing limits on future voters and generations from changing this status quo by legislating government debt and deficit limits or embedding practices in Government institutions.

The not-so-secret guard rails on Government spending and borrowing

The LGFA debt rules are, in effect, part of a suite of these limits and practices designed to keep public investment and debt low and to starve future generations of infrastructure and services, which has the effect of transferring wealth to home-owners now from renters now and future citizens. These practices include the position held3 across both major political parties for at least 30 years of limiting the size of Government and Government debt to less than 30% of GDP. This was confirmed again last week by the new Government.

The Labour Government committed to this 30/30 rule with the Green Party in its 2017 election campaign and stuck with a version of that until it lost the election last year. This is based on the 1989 Public Finance Act and the 1994 Fiscal Responsibility Act, which specifies Governments must keep debt at ‘prudent’ levels, which Treasury has specified is around 30% of GDP, with the agreement of both Labour and National Finance Ministers for 30 years, albeit Labour and National disagreed on the definition of Gross vs Net debt in the last election campaign.

Another tool in the suite is the rule in subpart 3 of the 2002 Local Government Act Section 100 (1) which states “a local authority must ensure that each year’s projected operating revenues are set at a level sufficient to meet that year’s projected operating expenses.” This effectively stops councils from running deficits, incentivising them to under-spend on maintenance. Councils have forecast they’ll spend only around 70% of their depreciation allocation on actual maintenance of assets for the last decade, the Auditor General reported in 2022. Various councils (page 24) have also hard-wired limits on rates increases in local statutes and policies, cementing in place the inter-generational transfer of wealth.

So how should or could we change it?

Currently, Governments from both sides have adopted the magical thinking that they could solve the infrastructure deficits by getting private investors to step in, and by using demand management (tolls, water charges and congestion) charges to reduce the size of the infrastructure bill. But, as the review makes clear, private funding through SPVs would produce less than 1% of the necessary funds, and those funds would cost upwards of 100 basis points more than simple Government or council borrowing.

In my view, the basic incentives for household (and therefore voter) investment would have to change to encourage investment in real assets and infrastructure by businesses and Governemnts, rather than investment in existing plots of residential land.

That requires the existing tax-free status on capital gains from land to change, and for Aotearoa-NZ to have the same incentives for retirement savings as other countries. There are currently none.

In my view, the following changes would allow Governments and councils to prioritise housing affordability, emissions reduction and poverty reduction, and create stronger private investment in assets and people that raise real wages and returns on capital:

taxing residential land through a residential land value tax that encourages and funds the investment in water and public transport infrastructure on already-zoned land to maximise the number of occupied, affordable and zero-emissions homes on that land;

incentivising investment in KiwiSaver funds with either a lower income tax rate for contributions or a lower income tax rate on earnings within the funds’ lifetimes; and,

repealing or amending the Public Finance Act, the Fiscal Responsibility Act and the Local Government Act to specify budget balance, debt, and public infrastructure levels that produce affordable and zero-emissions housing and transport for the next generations of voters, rather than minimising debt and public infrastrucuture for current voters.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

PS: By the way, the tax changes above are effectively a tax switch to start taxing wealth again and reducing tax private investment. It would also leave capital gains on real business investment untaxed. It would make owners of real business wealth (not land) richer, while also making housing more affordable and reducing the nation’s international climate change liabilities and event risks.

PPS: Appendix A: A brief history of debt and infrastructure (pages 47-54 in the review) is the absolute bomb. Graham Campbell, the Commission’s principle economist behind much of the review, deserves a medal.

The interview is available for all free subscribers in full.

Renters vote at significantly lower rates than home-owning voters in general elections, while home-owners totally dominate council elections, outvoting renters at a rate of 3 or 4 to one. That’s why councils typically favour the interests of suburban land owners. Median voters in general elections are much more likely to own their own homes than renters, which drives politicians to retain policies such not taxing capital gains, aiming to cut taxes and minimising investment and debt to keep mortgage rates as low as possible.

This is justified by Treasury and others by reference to the phrase