TLDR: The Reserve Bank has talked hopefully again about the chances the tide is turning on the ‘one-way bet’ for housing as an investment because interest rates are rising, houses are being built, tax rules have been tweaked and migration is low.

Should we believe the central bank this time? Paid subscribers can see more detail and my view that not that much has really changed to reverse the one-way bet below the paywall fold and in the podcast above.

Elsewhere in the news this morning here and overseas:

PM Jacinda Ardern announced a last-minute trade agreement with the EU that will dramatically improve access for our kiwifruit, fish and honey exports, but has disappointed meat and dairy exporters;

China’s Embassy here took the unusual step of issuing a statement directly criticising Ardern’s comments to NATO yesterday about China, calling them ‘unhelpful, wrong and thus regrettable’;

BNZ’s economists warned that a mild recession later this year could turn into a deeper one after seeing another sharp drop in business confidence in ANZ’s survey for June;

The US Supreme Court ruled overnight President Joe Biden couldn’t regulate to reduce carbon emissions from power plants Reuters;

Data for the US inflation measure most closely watched by the US Federal Reserve was slower than expected in May, which encouraged bond investors to push the key 10 year US Treasury yield down nine basis points to 2.99%1; and,

Ukrainian artillery and missile strikes drove Russian troops off Snake Island, although Russia said it was a tactical withdrawal to allow for grain exports. The Guardian

Is this time really different? I doubt it.

‘This time is different’ are the four most dangerous words to string together when talking about economic trends and asset values in markets, and this time is no different.

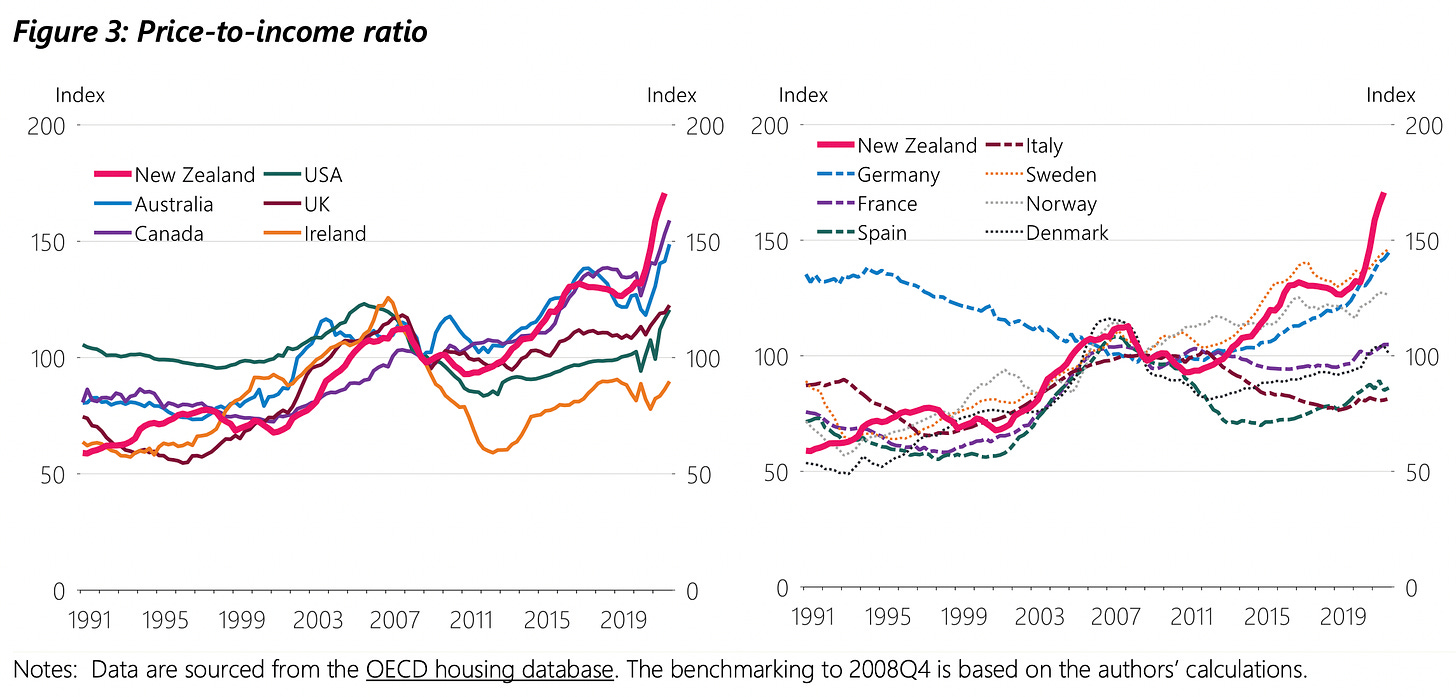

Yesterday, new Reserve Bank Chief Economist Paul Conway gave a detailed and comprehensive speech about the housing market to the National Property Conference, in which he was hopeful the tide had turned on the ‘one-way bet’ thinking behind the obsession New Zealanders have with buying property as an investment above all else, which in turn has made our housing the most expensive in the world.

Here’s the core of his argument (bolding mine):

“Over the years, the demand side of the New Zealand housing market was boosted by strong population growth, steadily declining neutral interest rates and a favourable tax system. The supply side, however, has been held back by strict land use regulations, and a construction sector prone to boom-bust cycles, while carrying very high building costs. Excess demand led to New Zealand’s experience with some of the highest house prices relative to income in the world.

“A sense of ever-increasing house prices – along with a lack of other quality local investment alternatives – may have also distorted the investment options of New Zealanders. The share of housing on household balance sheets is very high and commercial banks hold a high share of mortgages on their balance sheets.

“Rapidly increasing land prices may have also led to a transfer of wealth to people who owned land as prices were rising from landless younger people and future generations, who have to spend more to buy land. This means that they save less, reducing the amount of alternative capital they own and possibly lowering lifetime consumption and incomes.

“Are these dynamics likely to continue in future? Since August 2021, the Reserve Bank has been tightening monetary policy, lifting the Official Cash Rate, to rein in inflation. This will likely see actual house prices move back towards sustainable levels that are more in line with market fundamentals. Indeed, in the May Monetary Policy Statement, we forecast a 15% decline in house prices from their peak, which would bring them roughly back to sustainable levels.

“Over a longer time frame, there are reasons to think that some of the core market fundamentals that determine sustainable house prices may also be changing. On the demand side, as the pandemic slowly recedes and international travel restrictions unwind, many New Zealanders are heading overseas seeking new experiences. On the other hand, immigration is unlikely to return quickly to pre-pandemic levels, contributing to slower population growth overall.

“In the tax space, the removal of interest deductibility and the introduction of a capital gains tax on sales of residential property owned for less than 10 years – the ‘bright lines test’ – will have closed some of the gap between the effective tax rate on housing and other asset classes.

“At the same time, urban planning rules are being freed up to unlock more housing supply. The Resource Management Act is being replaced and the National Policy Statement on Urban Development directs councils to remove overly-restrictive planning rules and to enable higher housing density, which is a critical part of the solution.

“In the construction sector, the Commerce Commission is carrying out a market study into competition for residential building supplies in New Zealand is working well and, if not, what can be done to improve it. These changes are consistent with more houses being built and currently high building consents translating into more actual houses. They also imply that housing market dynamics in future are unlikely to be the same as in the past. Given the importance of housing in our economy and national psyche, this will be a huge change.

“For several decades, we have traded houses among ourselves at ever-increasing prices in the belief that we were creating prosperity. But the tide may well have turned against housing being a one-way bet for a generation of Kiwis. We need to keep building a new approach to housing and economic prosperity in Aotearoa-New Zealand.” Reserve Bank Chief Economist Paul Conway in his first major speech yesterday.

Let’s check those assumptions

I suspect the Reserve Bank is being premature and a little too hopeful in saying the tide is turning. Here’s why:

longer term mortgage interest rates here may have already peaked2 and it’s not clear at all that the multi-decade fall in ‘neutral’ interest rates is about to be reversed;

migration may have stalled for the last two years, but the political drivers to unleash 2%-plus per year increases in population through migration of temporary workers remain firmly in place3;

construction industry confidence has collapsed back to 2008/09 levels in recent months as house prices have started falling and bank lending has dried up, which means assumptions about supply becoming more flexible are premature, especially given industry structures, staffing and productivity remain predicated on such boom-bust cycles;

infrastructure funding to allow councils to pay for the pipes, roads and other services for their newly-upscaled district plans remains unresolved and NIMBY-dominated councils continue to push back and water down the Government-ordered intensifications at every turn4

the Government’s insistence (both National and Labour) on keeping net debt and the size of the Government’s tax share at or below 30% of GDP has prevented the Crown from funding the transport and water infrastructure to enable the intensification, and will do so for the foreseeable future;

the tax incentives powering the ‘over’ investment in housing remain in place, with both Labour and National seeing capital gains and wealth taxes as unacceptable to the median voters that decide elections; and,

the assumption about the Commerce Commission (and ultimately any Government) actually acting to improve competition in building materials to reduce construction costs is optimistic at best, given its track record with supermarkets was to abandon an industry breakup proposal with its final report.

Haven’t we been here before?

The broader problem for the Reserve Bank in trying to reset expectations is that it has tried before and this latest warning risks being another ‘boy cried wolf’ moment.

As I’ve reported before, here’s the lineup of boys crying wolf:

April 1998: Reserve Bank Governor Don Brash warned rental property investors expecting unending and high capital gains would be disappointed: “Far too many people still see getting heavily into debt to buy a second property as the best way they can save for their retirement, even though, in my view, they will be disappointed.” House prices have risen 330% since he said that.

August 1998: Brash said house prices were likely to rise in line with other inflation of around 2 per cent: “Property investment is not a low risk activity in a low inflation environment, and urging people of limited means to borrow heavily to undertake it puts them at risk of serious loss in today's circumstances.” House prices have risen 328%.

September 2003: Reserve Bank Governor Alan Bollard said after house prices rose 14 per cent in the previous year that rental property investors should soon expect real deflation: “I'm concerned that this could end in disappointment, especially for unsophisticated investors rushing to get on the housing investment bandwagon.” Prices have risen 218% since he said that.

September 2004: Bollard said the success of housing as an investment depended on the prospects for capital gains in the coming years because yields from rents were so low: “A reasonable view is that house prices are unlikely to rise much further over the next two years, and some falls are certainly possible, particularly in some regions,” he said. Prices have risen 174% since he said that.

June 2006: Bollard told central bankers in Switzerland that New Zealand house prices would start falling by the end of 2006 as higher interest rates took effect. House prices have risen a further 118%.

February 2015: Reserve Bank Governor Graeme Wheeler warned there could be a sharp correction in house prices. Prime Minister Sir John Key supported that warning, saying: “We are building a lot of houses in Auckland now. People can get a bit carried away with the fervour of these things and believe it is all going in one direction. History shows you house prices go up and down.” Finance Minister Bill English said: “There's no asset price that can go up at over 10 per cent a year forever, so sometime it will stop. And in this case we are really starting to get more supply coming at speed into the market.” Prices have risen 58%.

September 2015: English said the Auckland housing market was on fire and people needed to be careful not to get burned when prices fell. Wheeler also told MPs that month that Auckland house prices were not sustainable. “The house price to income ratio for Auckland is at nine. It's twice that for the rest of the country. A ratio of nine puts you, according to Demographia figures, in the top 10 most expensive cities in the world. This is just dangerous territory.” Auckland prices rose a further 38.6% since they said that and Auckland’s house price-to-income multiple is now almost 11.

March 2017: Wheeler said Auckland house prices faced a heightened risk of a sharp correction because of the risk of higher interest rates and the number of homeowners with high debt-to-income ratios. Finance Minister Steven Joyce said the tide of rising house prices was turning because of rising supply and a likely rise in interest rates from 50-year lows. “People would be mistaken – while you can never pick the turn of the market – they'd be mistaken to think house prices will keep going up the way they have.” Prices have risen 25% since they said that.

September 2017: English and then opposition leader Jacinda Ardern in an election debate were asked if they wanted house prices to fall, English said: “I want them to stay flat while incomes rise.” Ardern said: “We don't want them to lose their value, but we want more affordable housing in the market as well, and that is what is missing.” Prices rose 23.9%.

The too-big-to-fail problem

The other bigger problem unaddressed in Conway’s speech, but still in the back of everyone’s mind, is that even if the Reserve Bank thinks house prices are over-valued and therefore likely to fall, the housing market is different to other asset classes in three major ways:

our banking system is now reliant on house prices remaining elevated to support its profits and asset base, with a serious slump (50%-plus) to properly affordable prices being unthinkable from a financial stability point of view;

the Reserve Bank’s own research has shown that a collapse in net wealth because of a crash in the housing market would rebound into the real economy as home-owning consumers would be expected to reduce their spending by around five cents in every dollar of wealth destruction5; and,

a crash of 50%-plus would not be acceptable politically and would trigger a change of Government and or policies to stop such a fall6.

I hope this time is different, but this isn’t my first rodeo. Assuming a hands-off approach to asset prices, I expected the Reserve Bank and the Government to allow house prices to fall 30% in 2008/09. They didn’t, and they repeated those actions in 2020 to stop a collapse. They would do so again, possibly even before the year is out.

Realistically, the housing market is not only too big to fail. It is too big to be allowed to fall too far. The Reserve Bank has already said a 15% fall from November’s record high is far enough to be ‘sustainable’. That would take prices back to where they were in early-2021 and mean home owners ‘keep’ at least half the 20% rise between the March 2020 interventions by the Government and the Reserve Bank and that peak in November 2021.

A Reserve Bank that believed house prices should and could return to affordable levels would expect and not intervene to stop a 40-50% fall to levels relative to incomes and rents last seen in 2003. The fact the bank and the Government baulked at the idea of including affordability (rather than ‘sustainability’) in its mandate tells you everything you need to know. Neither have even suggested which level of affordability they prefer to use or where it should be.

A Reserve Bank that was determined to reset expectations would use its tools to drive actual prices to those affordable levels, which it could do with interest rate and/or bank capital controls. The last time expectations about prices (CPI inflation) were out of control was in the 1970s and 1980s. The collective response then was to rewrite the Reserve Bank Act, give it independence and allow it to create a brutal recession to drive expectations lower. Neither the Government or the bank intervened to reverse or stop the political and economic pain. Those resetting of expectations then were a feature — not the bug.

More jawboning to try to convince homeowners they are wrong to keep seeing houses as the highest returning investments7 will fail unless it is backed by the political and regulatory changes to make it happen. Hoping it will happen is not enough. We’ve been here before. It didn’t work before and it won’t work again.

So how could it be done?

These are the things needed to actually return house prices to affordable levels:

changing the tax incentives for residential land ownership by taxing either the capital gains for all homeowners, or taxing the value of land, especially unoccupied residential zoned and serviced land, as well as capturing the capital gains from rezoning or public infrastructure investment through ratings uplift capture rates;

changing the collective political views about acceptable levels of public debt and the tax share of the economy from the current ‘consensus’ of at or below 30% of GDP for both net debt and the tax share of GDP so the Government and Councils can invest in housing and transport infrastructure; and,

collectively deciding to target a housing affordability measure and giving independent Crown agencies the power to drive house prices and rents there, regardless of the effects on household wealth and inflation.

Median-voting homeowners can’t see any other way. Yet.

None of these things are politically viable in the current environment. So I wouldn’t expect much to change, and most median-voting homeowners know that in their bones. That’s why they effectively have accepted the National and Labour policy prescriptions over the last 30 years to keep net Government debt and tax at around 30% of GDP and to keep capital gains on owner-occupied residential land tax free.

The only way that might change is if those same median-voting households realise they are enabling and supporting the creation of an increasingly unequal two-tiered society split between home-owning families and renting families. The biggest pressure point for those home-owning median voters is the situations of their children, and whether they are prepared to keep donating equity to children for deposits, and/or having to watch their grand-kids grow up on skype or whats app, or on brief visits to Australia etc.

So far, none of the polls or policy prescriptions I’ve seen would suggest we’re anywhere near that sort of tipping point.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

That would be the US 10 year’s first close below 3.0% since June 7.

Tony Alexander wrote in his Tony’s View yesterday he expected the growing recessionary signs would mean the Reserve Bank would have to soon signal lower interest rates, which means longer term mortgage rates are likely to have already peaked.

“Following the latest round of increases in banks’ fixed mortgage rates there is probably not much upside left for the 2-5 year terms. The one year rate may have another 0.5% left in it.” Tony Alexander in his weekly note.

National have pledged to turn the migration tap back on fully if they win next year’s election and Labour is already loosening the restrictions as the opinion polls increasingly force a relaxation to both win back business confidence and control wage inflation pressures. Immigration NZ only this week increased its estimate of the number of successful Covid-era residency applications to 202,342 from 165,000. RNZ

Auckland Council voted last night to protect 15,000 villas in central suburbs from intensification, Stuff’s Todd Niall and the NZ Herald’s Bernard Orsman reported last night. Meanwhile Wellington City Council voted this week to water down its intensification plans, The Spinoff’s Jacob Flanagan reported yesterday.

For example, a cut of $1t in household net wealth (which would equal the rise seen since Covid) would see a $50b reduction in consumption, equivalent to a 15% cut in GDP, which would be the equivalent of a depression;

National’s rise in opinion polls has correlated almost directly with the fall in house prices since October last year, with new leader Christopher Luxon pledging to reverse interest deductibility and brightline rules making rental property ownership less attractive. He has also pledged to reverse the Three Waters reform, which is the Government’s solution to the housing infrastructure funding blockage.

Relative to equity invested, after-tax returns, volatility and liquidity (ie leveraged returns from tax-free capital gains that are less volatile and more liquid than other types of investments)

Share this post