Long stories short, here’s the top six news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa-NZ this week, and a discussion above between Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer:

Central Europe is reeling from the devastating effects of Storm Boris, which has so far caused 21 deaths and left a wide swathe of destruction. Climate scientists say they aren’t surprised by the intensity of the storm, but troubled by the unpreparedness for such flooding events, despite all their warnings.

There has been a somewhat tepid media response to Simon Watts’ testing of the waters last week on the Government’s preparedness to pay for international carbon offsets to meet Paris Agreement targets. His suggestion the Government does not intend to cough up for ‘politically unrealistic’ costs was a whisker away from admitting that the coalition government intends to renege.

An article in the Atlantic this month blows open Microsoft’s claim that its massive investment in AI will lead to solutions for planetary crises. Instead, the company is making a far more substantive contribution to worsening the crisis by actively pursuing deals, valued at between US$35 billion to US$75 billion annually, with the fossil fuel industry to sell its AI for the purposes of optimising and automating drilling to maximise oil and gas production.

New non-solutions to climate change continue to arrive thick and fast as old non-solutions collapse in what George Monbiot refers to as ‘‘perceptionware’.

The Environment Ministry has opened up a public database of detailed climate projections by NIWA.

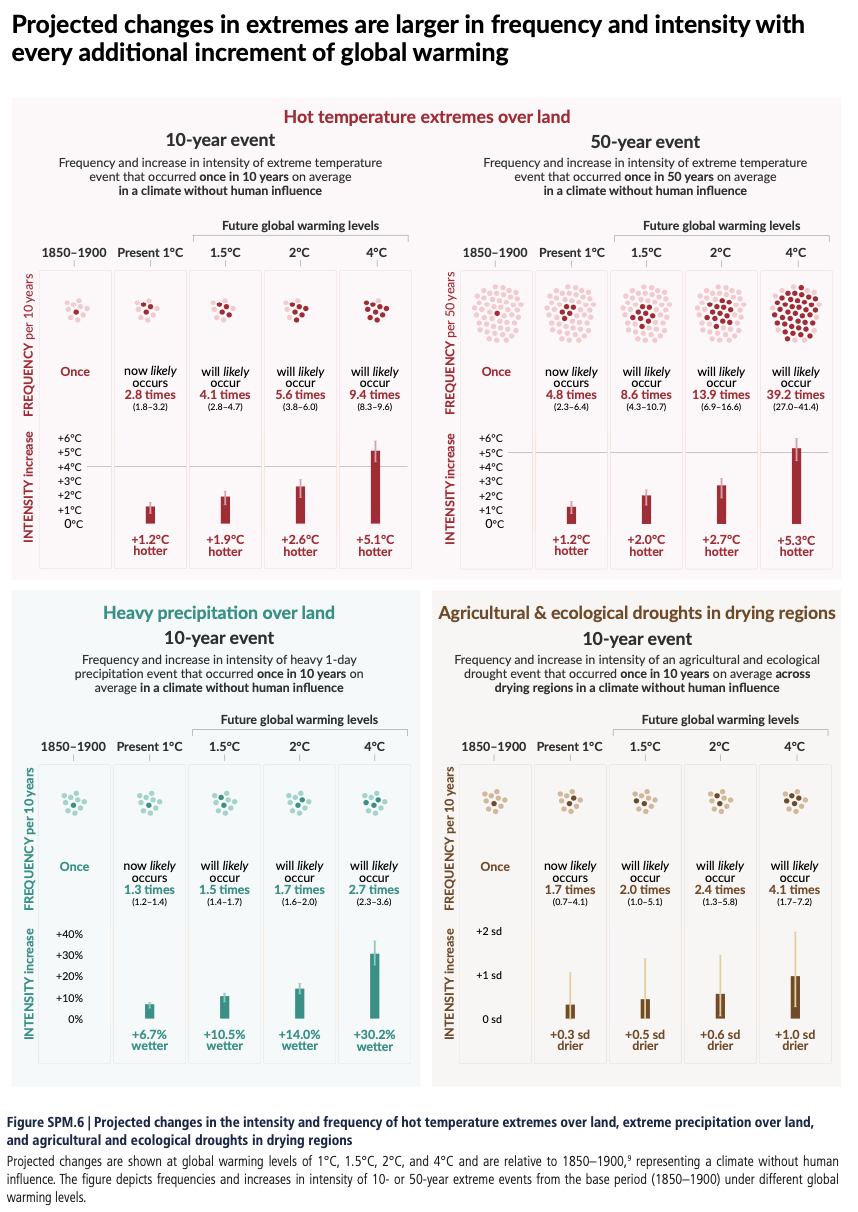

Chart of the week from the IPCC’s Working Group I report shows projected changes in extremes are larger in frequency and intensity with every additional increment of global warming.

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the video and podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

1. Deadly consequences of failing to prepare

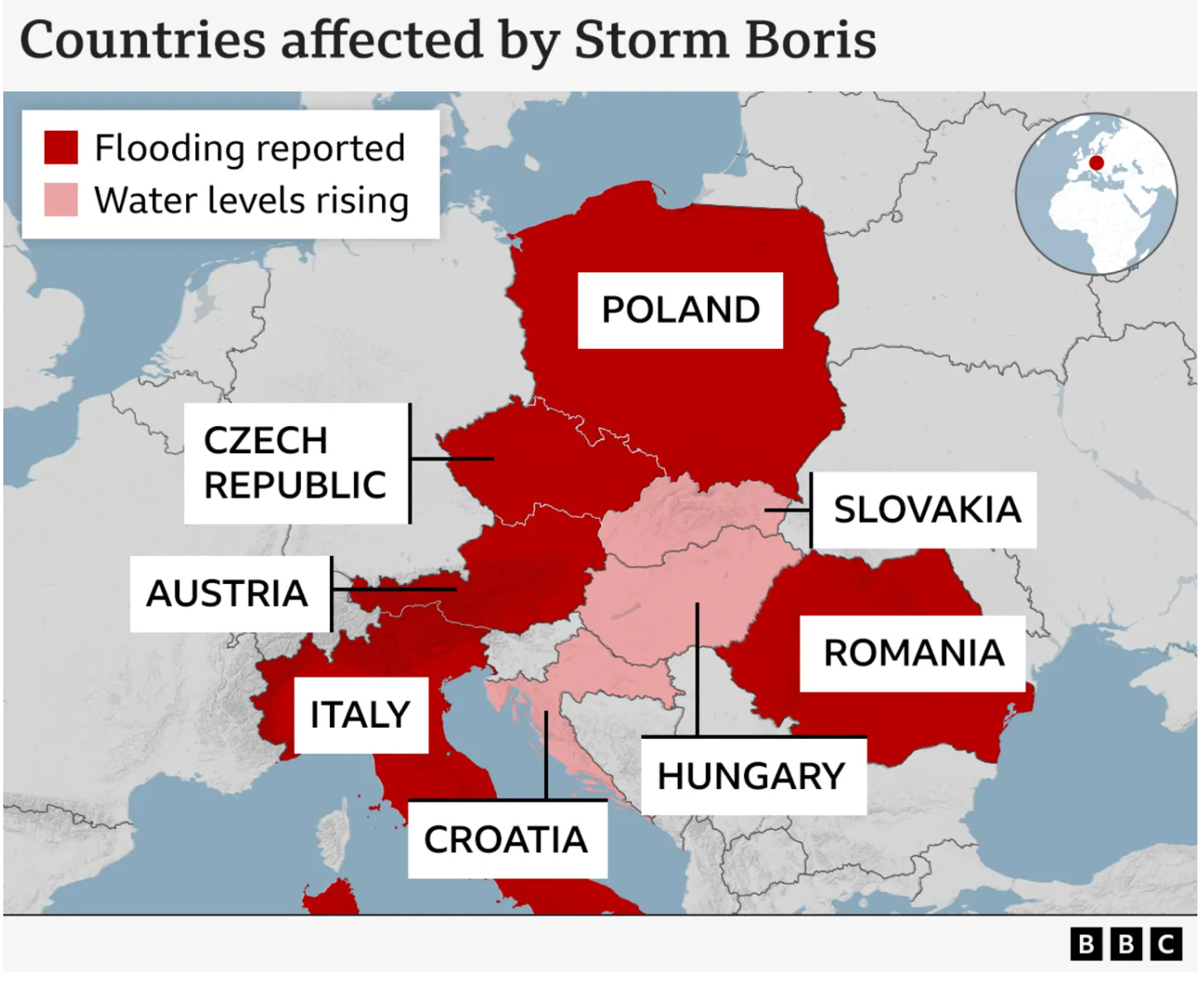

Flooding in central European countries caused a swathe of destruction and 21 deaths so far in Austria, the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Croatia and Hungary this week. Italy is now bracing for impact from Storm Boris, with warnings issued for heavy rain, strong winds and floods. Poland’s Prime Minister, Donald Tusk, has declared a month-long state of natural disaster.

Source: BBC

“Climate scientists say they are troubled by the damage but unsurprised by the intensity. “The catastrophic rainfall hitting central Europe is exactly what scientists expect with climate change,” said Joyce Kimutai, of Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute.

She said the death and damage across Africa and Europe highlighted “how poorly prepared the world is for such floods”. Guardian

Sonia Seneviratne, a climate scientist at ETH Zürich pointed to the extra heat absorbed by oceans that result in more water evaporating into the air.

“On average, the intensity of heavy precipitation events increases by 7% for each degree of global warming,” she said. “We now have 1.2C of global warming, which means that on average heavy precipitation events are 8% more intense.” Guardian

A recent study by Niwa climate scientists in Aotearoa attributed an additional 10% precipitation to human-caused climate change during Cyclone Gabrielle, which caused 11 deaths and $3.5b in damages.

The suggestion that leaders and policymakers are at fault for failing to respond to warnings from climate scientists is entirely valid. But they have been receiving mixed messages from experts with economic modelling regularly advising them that climate-related damages will be relatively limited and that action is less urgent than the consensus of climate scientists describe.

Nicholas Stern, Jospeh Stiglitz and Charlotte Taylor criticised Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) for their failure to deal adequately with risk and uncertainty in a 2022 paper, highlighting the massive divide between the conclusions of climate scientists and the policy recommendations that emerge from IAMs. These are a primary tool for formulating policy advice to governments in regular reports to the United Nations (UN) by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Stern et al. (2022) conclude that IAMs offered limited value in answering two critical questions:

“They fail to provide much in the way of useful guidance, either for the intensity of action, or for the policies that deliver the desired outcomes.

In spite of these basic problems of methodology and sensitivity, the IAMs have had enormous influence, especially in the United States, and their shortcomings have had serious policy consequences.”

The repeated failure to recommend sufficiently stringent or urgent policy action will resonate with those readers who took note of a report last year from UK actuaries. The report looked at the use of climate scenario analyses by financial institutions and regulators, finding that they systematically underestimate climate risk and the economic damages that will ensue. These are the same climate scenario analyses that central banks, including our RBNZ, use to test countries’ financial stability.

Not only do the models systematically underestimate climate change uncertainty and risk, they have largely ignored or assumed away potentially catastrophic risks of the type that, according to Stern et al., most of the rest of the world wants to avoid.

2. Watts tests the water and gets a tepid response

A report carried by Carbon News last week, in which Simon Watts described the planned purchase of international carbon offsets to meet the country’s Paris Agreement targets as ‘politically unrealistic’, has so far failed to break into mainstream media coverage, apart from a paywalled article in BusinessDesk. It was, however, picked up by the UK-based Carbon Pulse which, like Aotearoa’s Carbon News, is widely read by carbon market experts.

Watts’ words have resonated with market experts alert to the risks intrinsic to New Zealand reneging on its international commitments under the Paris Agreement, particularly in relation to the country’s trade relationships. While Watts claimed that the government was ”absolutely categorically focused” on minimising the gap, the recently released Emissions Reduction Plan does not reflect that kind of effort. Instead, domestic policy enacted since the coalition government was elected has achieved the diametrically opposing effect of increasing domestic gross emissions.

It is incumbent on the Minister to clarify the discrepancy between what the government says it is doing and what is actually happening. The Minister was warned in a briefing by environmental officials, as recounted by RNZ back in February.

“Minister Simon Watts was told Aotearoa's international climate commitment for 2030 required significantly greater emissions cuts than were required by domestic legislation.

He was told the government needed to decide whether to scale up domestic action, or move ahead with international negotiations to buy carbon credits.

The new government has previously been wary of committing to buying international credits, but meeting the entire target with carbon cuts here would be big task and major change of direction.”

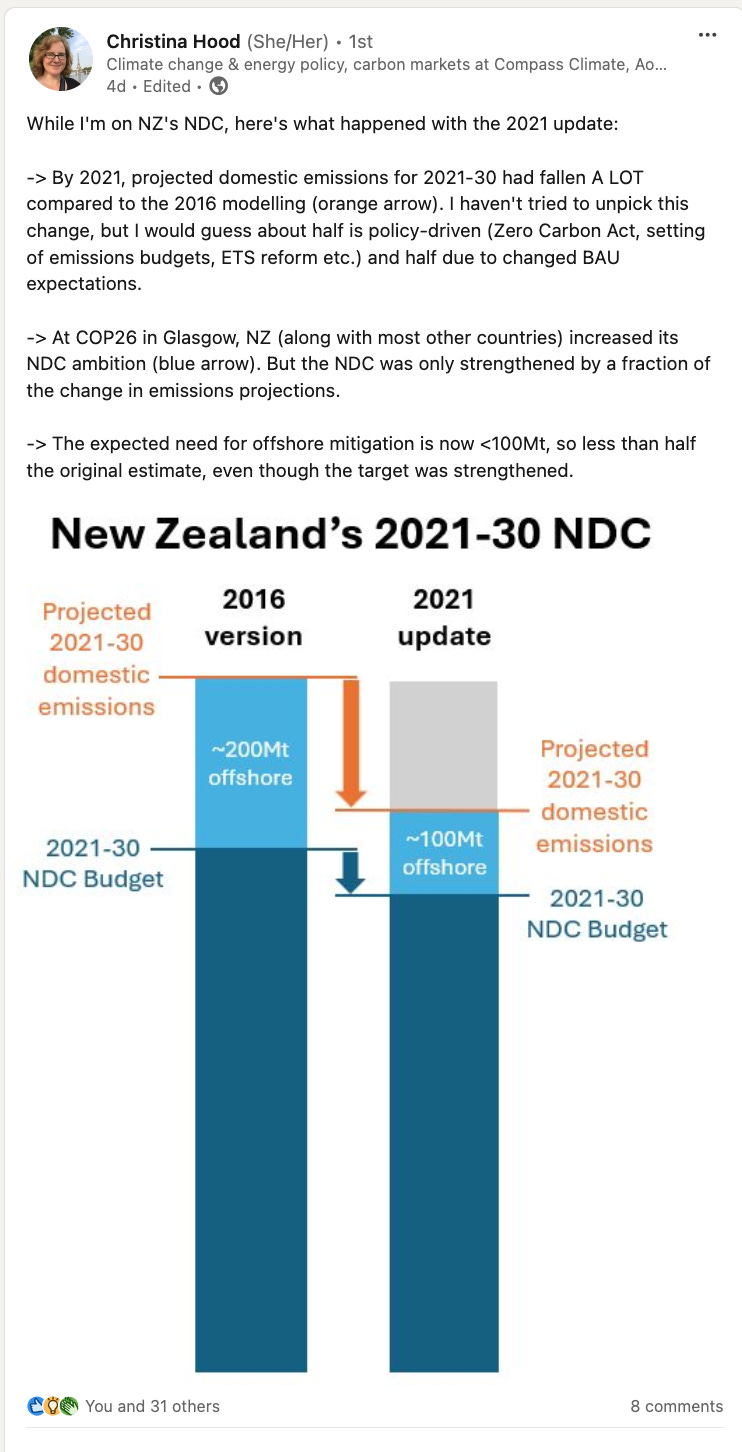

It is also worth noting that the quantity of international carbon offsets required in order to meet Paris Agreement targets was halved in 2021 under the previous government, indicating that such emissions reductions have been achieved before, in relatively short timeframes, through increased domestic action. Outlined here by carbon market expert, Dr Christina Hood:

3. The dark side of Microsoft’s AI services

An article in the Atlantic this month blows open Microsoft’s claims that its work on AI will lead to solutions for planetary crises like climate change and biodiversity loss. It turns out that while making those claims, Microsoft was actively pursuing deals, valued between USD$35 billion to $75 billion annually, with the fossil fuel industry to sell its AI for the purposes of optimising and automating drilling to maximise oil and gas production. According to journalist Karen Hao (who supplied a gift link to the article on Linkedin):

“Microsoft isn’t a company that exists to fight climate change, and it doesn’t have to assume responsibility for saving our planet. Yet the company is trying to convince the public that by investing in a technology that is also being used to enrich fossil-fuel companies, society will be better equipped to resolve the environmental crisis. Some of the company’s own employees described this idea to me as ridiculous. To these workers, Microsoft’s energy contracts demonstrate only the unsavory [sic] reality of how the company’s AI investments are actually used.”

Several ex-employees revealed their years-long internal battle to hold Microsoft accountable and to stop it from from using its AI to help fossil-fuel companies in a story that was jointly published by Grist and Drilled earlier this year. In it, they said:

“It’s true that Microsoft is taking numerous steps to address the sustainability of its own operations. But for years, the company has also furnished fossil fuel giants with cloud computing services and specialized software tools powered by machine learning and AI in order to streamline and automate their operations. These digital technologies help companies discover oil faster, squeeze more from existing wells, and boost productivity across their operations in order to stay cost competitive in an age of cheap renewable energy. The digital services market for oil and gas is “immense,” as a 2020 report by oil industry analysts at Barclaysput it, with the potential to unlock $150 billion in yearly savings for producers.

Over the past seven years, Microsoft has announced dozens of new deals with oil and gas producers and oil field services companies, many explicitly aimed at unlocking new reserves, increasing production, and driving up oil industry profits.”

4. A non-stop stream of non-solutions

George Monbiot calls the non-stop stream of non-solutions ‘perceptionware’, whose main purpose is to create the impression of action, even if that action will never scale up to a solution.

The latest in a long line of such non-solutions is an Italian scheme to dig up long-sequestered carbon dioxide in the form of limestone to make quicklime (a massively carbon polluting process), to then make bicarbonates to pour into the ocean, supposedly in order to ‘enhance’ oceanic carbon uptake. That and other cool ideas are described by Michael Barnard in Cleantechnica.

Meantime, one of the world’s largest proposed direct air capture (DAC) projects, known as Project Bison has collapsed. The project, proposed by a technology start-up backed by the Biden administration, had planned to remove five million tonnes of CO2 annually by 2030. The company, CarbonCapture, claims that it was unable to secure enough clean electricity to run the project. Ironically, the competition for electricity is coming primarily from tech companies who are investing heavily in schemes like CarbonCapture’s in an effort to offset their own increasing emissions.

5. Database of climate projections opens to the public

The Environment Ministry has opened up detailed climate projections by NIWA to the public. Anybody can visit the public database to view detailed information on drought, rainfall, wind and temperature projections under different greenhouse gas scenarios,

The move was welcomed by the Sustainable Business Council, which said getting access to robust climate data could be a challenge.

Many large companies now have to publish reports to investors on how different climate scenarios might affect their business.” RNZ

6. Chart of the Week:

The following chart from the IPCCs AR6 WGI report for policymakers (p.18) shows how every additional fraction of a degree of warming increases the frequency and intensity of extreme heat, precipitation, and drought.

Ka kite ano

Bernard and Cathrine

Share this post