TLDL & TLDR: The Government increased its Three Waters reform compensation offer to councils by $2.5b yesterday, but Auckland, Christchurch, Waimakariri and others remain opposed to what one Christchurch councillor described as “pocket change.”

This is the third increment of carrots in the Government’s process of trying to tempt councils to agree to hand over assets and debt from 67 water authorities to four new ones that will be able to borrow under their own steam to pay for the $120b to $185b of investment seen as necessary over the next 30 years.

The first one was $761m in July last year when the Three Water reform process was kicked off. Then there was another $296m in the May Budget this year. But most of the biggest councils remained unhappy and PM Jacinda Ardern announced the latest sweetener in a speech to Local Government New Zealand’s conference in Blenheim yesterday.

The $2.5b includes $500m to initially ensure that no council is “no worse off” from the reforms, while there’s $2b at a later date “to invest in the future of local government and community wellbeing, while also meeting priorities for government investment (the “better off” component)”. These background papers show Auckland would get $508m as part of that $2b.

Ardern made the point in her speech that the transfer of the assets and liabilities would give more borrowing capacity to some councils, given the current (arbitary) debt limits set by the Treasury-dominated Local Government Funding Agency are council revenue to debt limits, rather than debt to asset limits.

“This funding is on top of the extra debt headroom that the reforms will deliver for many councils.” Jacinda Ardern in her speech to the LGFA conference.

The associated papers also point out many councils that will be able to borrow more after the transfer of assets and liabilities.

“Initial analysis indicates that for most councils, the impact of reform is expected to have a positive effect on their borrowing capacity. Priority will be given to undertaking due diligence with those local authorities that are more likely to suffer adverse borrowing impacts. As an example, this will include councils that have a low level of water debt to revenue and a high level of non-water debt to revenue,” the Department of Internal Affairs wrote in its background papers.

The new water services entities would fund $1.5b of the Government package, with the Crown providing the rest.

Will it drag the councils on board?

The initial response yesterday from Mayors and councillors yesterday was lukewarm at best. Auckland Mayor Phil Goff said he remained opposed and wanted a ‘bespoke’ model carved out for Auckland so it didn’t have to subsidise water networks up in Northland. In particular, he was unhappy that the new enlarged Auckland plus Northland authority would see only 40% governance representation from Auckland when Auckland was contributing 92% of the assets and 90% of the population. (NZ Herald)

Christchurch, which was offered $122.4m of the $2bn ‘better off’ fund, appeared to remain sceptical. Mayor Lianne Dalziel said the offer had raised many questions, while councillor Aaron Keown said it was “pocket change” and for “Christchurch to fall for a bribe of $120m is not a good idea.” (The Press) Waimakiriri Council and the Whangarei Council have also opposed the reforms.

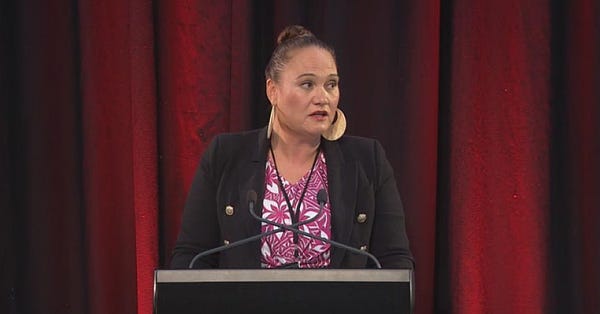

But Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta still has the big stick in her back pocket of forcing the reforms through with Parliamentary legislation. She has left that option open, and the papers were non-committal on whether those that opt out would get their share of the pot if the Government was forced to legislate over the heads of councils.

The sadly devilish detail

The political sensitivities are many and varied, and often depend on the historic approaches the various councils have taken to water charges, infrastructure investment and the use of debt. Some councils haven’t invested, haven’t charged for water and haven’t got big debt. Some have invested, have charged for water and do have more debt (Auckland), while others (Wellington and Christchurch) don’t charge for water and haven’t borrowed or invested as much themselves. The caveat is Christchurch’s networks were rebuilt with a lot of Crown money after the earthquakes.

The perceived ‘fairness’ of these settlements is a nightmare for councils, the DIA and the Government to navigate, with plenty of room for populist councillors and mayors to take easy shots at ‘big Government centralisation’ in their campaigns ahead of next year’s council elections. There are also incentives to throw political hospital passes to the Government around water charges and long-planned catch-up investment.

Decisions about whether water charges will be imposed, how much underinvestment councils are ‘allowed’ to get away with in any settlement, and whether debt-using councils suddenly get big licks of fresh borrowing headroom, are unknowable for ratepayers and others without this sort of detail, which is always devilish.

The incrementalism and the Public Finance Act are not working

My view: The Government is now in this predicament because it took the usual MMP-style incremental political and financial approach to a reform that is anything but incremental. It started out hoping $761m would be enough, and is now up to $3.5b of carrots. It should have started with the latter number to avoid these local revolts, which are now threatening to join up with other unrelated provincial unhappinesses over water quality standards, winter grazing rules, climate reform fears and the ‘ute tax’ into a crescendo of farm vs city anger. Watch out for that later today in today’s ‘Groundswell’ protests up and down the country.

But that incremental approach is not just about the cultural DNA now ingrained in our politicians and bureaucrats that only incremental reforms work. It’s also a result of the overall apparatus of Governments’ still-enthusiastic adherence to the Public Finance Act 1989’s directive for the Crown to always look to reduce debt, and in effect ‘starve the beast’ of Government by underinvesting in infrastructure. The PFA was written in an era when bond vigilantes could and did beat up Governments for profligacy by slashing credit ratings and pushing up interest rates. It was also written at a time when we thought our population would be mostly flat and ageing, and therefore we didn’t need much more infrastructure.

2021 is not 1989

Both those assumptions are wrong and the 1989 view of the world is long over, at least in the rest of the world. The bond vigilantes have been euthanised by low inflation and low interest rates, and NZ has just gone through 20 years of explosive population growth that was not prepared for or ‘infrastructured’ for. We now face at least three decades of heavy investment in water, climate, transport and housing infrastructure to both catch up on past under-investment and to fix our massive climate and housing affordability deficits.

Treasury, DIA, the Government and councils have yet to understand both the scale of the deficits and the threat of future political backlashes by voters who are beginning to understand the breadth and depth of the intergenerational wealth transfer orchestrated over the last 30 years ($1 trillion and counting).

The Government and Treasury have restrained themselves from thinking much longer term on these issues because it believes it is debt constrained. The PM even repeated that view in her speech yesterday, referring to council debt constraints in her argument for the reforms.

“The entities will address the affordability challenges through: superior long-term financing arrangements delivered by separating balance sheets from debt-constrained councils; the ability to spread costs across larger populations over time.” Jacinda Ardern.

The implication is the Govt is less debt contrained, which is some progress, but the councils themselves are only constrained by the LGFA’s Treasury-driven edicts about debt to revenue ratios being less than 300% this year and falling (!) to 285% by 2025.

Both Government and LGFA bonds are currently trading at well less than 2%, which means real interest rates are negative.

What’s missing in the Government’s approach is a wider and longer strategy about how to solve these problems of climate change, water quality and housing affordability. They can’t be solved with the current Public Finance Act, or at least the way it is interpreted. Treasury is beginning to edge forward with talk in recent weeks about using the balance sheet to solve these longer term problems, especially when the costs are so low and the potential returns so much greater.

The problem with the group-think of incrementalism

But this incrementalism in both the political and financial group-think in Wellington just won’t be big enough or fast enough to deal with the twin emergencies of climate change and housing affordability.

For now, the debate will focus on each of the ‘deals’ offered to councils and the varying individual situations they are in. Trying to design micro-targeted and ‘fair’ packages that reflect the historically different approaches to investment, the use of water charging and the use of debt is yet more incrementalism. Councils will have to make their own decisions about what is fair, and how much political pain they want to offload back onto the Government.

For example, Auckland has already taken the pain of creating Watercare and imposing water charges. It could be argued Auckland has also subsidised the rest of its operation through those charges to keep its overall debt low (remember ratings agencies don’t see water authority and other council debt separately). Losing its ability to cross subsidise the rest of the Council will be painful to give up and it will want more than $508m in compensation.

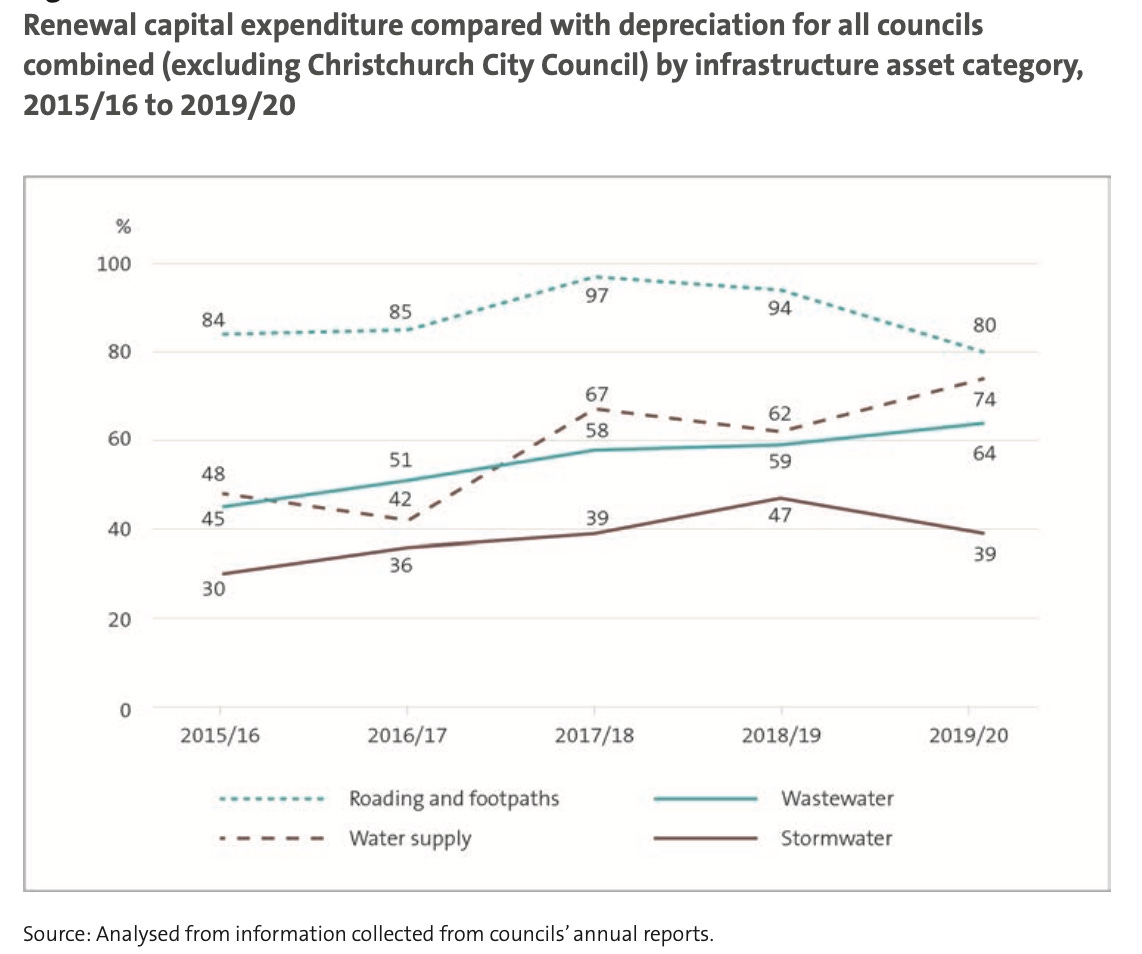

Also, for example, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin don’t impose Auckland-style volumetric charging on households. It may suit councils to shuffle that decision up to the new authority and then blame the Government when the charges arrive. The creation of these authorities could also be used as cover for pushing difficult decisions around funding past under-spending relative to depreciation charges to the Beehive.

Unresolved other issues

The problems for the Government are not just political and financial. They’re also timing and process problems. The Three Waters reforms are happening before Local Government Funding Reforms and before any sort of resolution over water control with iwi. Doing financial settlements with Councils before these other issues are resolved is putting a big cart in front of several horses.

Again, the scrambled nature of these reforms, in tandem with RMA reforms, Building Code reforms, DHB reforms, Climate change reforms and welfare reforms, is a function of this incrementalism groupthink and the outdated and unrealistic financial parameters set by the Public Finance Act.

This rolling cluster-mess is also a lost opportunity. This Government has a potentially once-in-a-generation Parliamentary majority, a popular leader, a dysfunctional Opposition and benign borrowing conditions. Now would have been the time to adopt a more strategic and long-term approach that used the Crown’s balance sheet and rallied the various arms of Government to deal with these emergencies in a substantial, fair and durable way.

That’s not happening.

Scoops and breaking news this morning in brief

Signs o’ the times news

Share this post