TLDR & TLDL: The latest Reserve Bank and Government attempt to slow a still-hot housing market only highlights the problem of trying to solve an affordability problem without allowing or encouraging big drops in house prices. Every move to tighten lending to new buyers advantages those in the market for the longest with the most equity, and hits those yet to get into the market and first home buyers hardest. There is no way around it.

It is the perma-curse of the endowment effect in our political economy. Fixing an inequality problem can’t be solved without someone giving up something.

The problem is now too large to be gently grown out of over time. Achieving affordability by simply suppressing house price inflation, rather than causing deflation, would take a century of waiting.

Property-owning voters are fighting the hardest and voting the most to hold on to their endowments of $1.54t of housing. In the process, they and their politician representatives are not only locking out those wanting to ‘get on the ladder’ to win a share of the bounty, but actually increase their own power to capture more of the tax-free, leveraged and effectively government-guaranteed capital gains on offer.

Here’s how it is (not) working

In another desperate attempt to cool a market super-heated by low interest rates (set by the Reserve Bank), the Reserve Bank yesterday announced plans to further restrict low deposit lending, to potentially bring in limits on Debt-To-Income (DTI) multiples, and to officially impose debt serviceability thresholds known as interest rate floors that banks already use informally. The central banks said it wanted to halve the allowance for lending over 80% LVR to 10% from 20% currently. This is know as ‘reducing the speed limit.’

But the trouble for the Government and Finance Minister Grant Robertson in particular is that all of those measures will hit first home buyers the hardest. First home buyers were responsible for 77% of the $3.208b of bank loans with Loan to Value Ratios (LVRs) above 80% in the four months since the re-imposition of LVR rules on March 1. Landlords were lent just $17m or 0.5% of those high-LVR loans. Luckily at the moment, the total of high LVR loans was collectively worth 8.8% of total new mortgage lending in the four months to the end of June so any halving won’t be drastic or immediate. The banks are already within the letter of the of the new limit.

However, banks like to keep a big buffer between their lending and the actual speed limit. The Reserve Bank also cautioned them yesterday it wants them to operate within the ‘spirit’ of the change, rather than wait to October 1 or use a ‘black letter’ approach.

If they change their lending practices in line with the Reserve Bank’s guidance for halving ‘risky’ lending with LVRs over 80%, almost all the burden would fall on first home buyers. It is the same with DTI limits, although it will depend on how high the threshold is set to determine the scale of the damage for first home buyers. For example, 80% of the lending to first home buyers in the March quarter (the latest data published by the Reserver Bank) was done at at DTI of over four, which is the threshold typically set overseas in the last decade (although most expect a five or six threshold more likely here now)

Also, over a third of lending to first home buyers is done with a LVR of over 80% and with a DTI over four. It is this lending that is seen as the riskiest, given it is to buyers with the least equity and least room for job losses or income loss in the event of an economic downturn. It will be the first to be dropped by the banks when they have to reduce their risk profile, which is the Reserve Bank’s main aim.

First home buyers are also the most likely to be closest to the interest rate ‘floor’ or serviceability limit that the Reserve Bank looks set to impose very quickly. This is the tool all banks use to assess whether they should lend to someone. They work out how much spare disposable income a borrower has after their regular spending on food, power, transport etc and then works out whether they can afford the loan if the interest rate rises to a certain threshold. At the moment most banks set that at between 6% to 6.5%.

A triangulation of risk reduction squeezing first home buyers

All this means is that LVR limits, DTI limits and interest rate floors effectively triangulate to stop lending to the riskiest borrowers with the least equity, the most income stress and the most income risk. That is almost by definition going to be first home buyers because the longest-owning property owners are typically more established in higher paying jobs, have much bigger equity buffers, and have the least disposable income stress because they have not just spent years renting and repaying student loans.

This system of macro-prudential controls has therefore become a way to embed and further widen the inequality already evident in the housing market in favour of older, richer and higher income owner-occupiers, especially the ones with multiple properties.

The fairest solution is a large and rapid price reduction that reduces the equity of those in the market and reduces the borrowing pain and risk for those getting into the market.

The other problem with these macro-prudential tools is they are the only ones the Reserve Bank can use to fix an affordability problem created by Government policies over the last 30 years. But using them simply entrenches that problem, especially when the Government also doesn’t want prices to fall.

However, the more pernicious problem for first home buyers is that these tools are presented as a solution to the problem and can reassure existing property owners, voters and politicians that ‘something is being done’. They are is an effective cover for further entrenchment of inequality.

The appearance of doing something

It is a particular problem for the Government because it wants to appear to be helping, or at least not hurting, those who want to get into the market, without hurting its chances of re-election by actually forcing a price reduction that median voters do not want. That is the balance it says it wants to strike ie somewhere between the two, but the balance has actually already struck totally in favour of home owners. The actual problem is that this is a pretence, as the numbers above show. Any action to restrict lending risk will hit first home buyers the hardest and the most because they are the ones with the lowest equity buffers and most serviceability risk.

Finance Minister Grant Robertson did that again yesterday when he announced he approved of the Reserve Bank’s additions to its macro-prudential tool kit, but waved a clause in the air to say his approval was conditional on the bank doing all it could not to hurt first home buyers. The bolding is mine.

“I have largely agreed to the Treasury and Reserve Bank’s proposed update to the MOU to add debt serviceability tools, but as I indicated in June this extension should not unduly impact first home buyers.” Grant Robertson.

However, the word ‘unduly’ can cover a lot of pain, and the detail of the Memorandum of Understanding signed on Monday gives plenty of caveats and wiggle room to explain away the obviously contradictory policy: ie Macro-prudential controls will always hit first home buyers first and hardest. The bolding is mine.

“In the design and implementation of a debt serviceability restriction, the Reserve Bank will need to have regard to avoiding negative impacts, as much as possible, on first home buyers, to the extent consistent with the Bank’s purposes and functions under Part 5 of the Act.” MOU signed by Adrian Orr and Grant Robertson.

‘As much as possible,’ gives plenty of room to move, along with the mention of Part 5 of the Reserve Bank Act, which specifies the central bank must “…avoid significant damage to the financial system that could result from the failure of a registered bank.” That clause means the Reserve Bank must stop banks from doing the riskiest lending, which by definition will mean first home buyers in a market where prices are not allowed to fall.

The detail in the announcement

The Reserve Bank announced it would tighten the speed limit on high LVR lending by owner-occupiers by reducing the allowed percentage of 80%-plus loans to 10% from 20% currently, starting October 1. It also said it wanted to look at introducing Debt-to-Income (DTI) restrictions and/or interest rate floors “in an effort to provide further comfort that borrowing is sustainable.”

RBNZ Deputy Governor Geoff Bascand said introducing DTIs would take longer, “whereas the banking industry has informed us that interest rate floors could be implemented more quickly.”

Governor Adrian Orr said in a statement house prices were “above their sustainable level,” so the central bank was “now considering tighter lending standards to reduce the risks associated with excessive mortgage borrowing.”

So what? - The Reserve Bank’s reintroduction of LVR controls with a 20% speed limit, along with the Government’s planned removal of interest as a tax-deductible expense for landlords, obviously hasn’t slowed the house market enough (or much at all). It might further slow demand. Interestingly, the tightening only applies to owner-occupiers (which includes first home buyers) and not landlords.

The slight surprise in the announcement was that restrictions on high LVR loans to landlords were not restricted from the levels imposed from May 1 of having just 5% of loans to landlords being at LVRs of over 60%.

Somewhat interestingly, total lending to landlords at an LVR over 70% (the previous limit pre-Covid) was $319m in total in May and June, which was 10.6% of total new lending to landlords. That would appear to be in breach of the new rules, although it’s not exactly clear what ‘this category’ the rule: “High-LVR loans can make up no more than 5% of a bank’s total new lending in this category.” It could either mean total new mortgage lending to all types of buyers, or just total new lending to landlords. I am checking with the Reserve Bank today.

The bottom line: The Government just pulled up the ladder a little bit higher on young renters, but is pretending it isn’t. It will probably get away with this virtue signalling because the Opposition has the same fundamental problem. It cannot complain about the ladder pulling exercise unless it is willing to encourage price reductions, which it has not and will never do.

Only the Greens and TOP want price reductions, and they are both irrelevant in the current political environment respectively. That’s because Labour can take the Greens for granted safe in the knowledge they will never back a National-led Government, and TOP are not close enough in the polls to the 5% threshold for supporters to safely put their votes.

Briefly in the news elsewhere

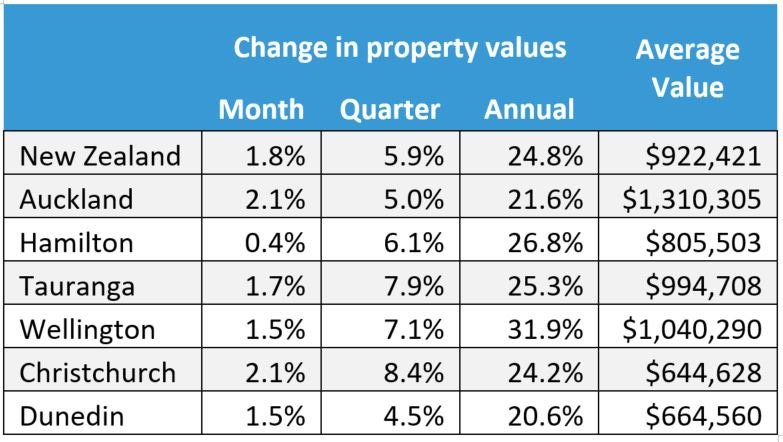

Still too hot - CoreLogic reported last night house values rose a further 1.8% in July, which was the same monthly growth rate as June and would translate into annual inflation of 21.6% if it continued at that rate for the next 10 months. Growth in the last three months was 7.2%, which would translate into annual growth of 28.8% if it continued at that rate for another three quarters.

“While we’re likely to be past the peak growth rate, a market this size can take some time to slow. Evidence of the strong momentum in the market could also be seen in the latest RBNZ lending data where new residential mortgage lending remains elevated compared to the long-run average prior to the pandemic.

“The exceptional rate of growth witnessed following the economic recovery after the pandemic-induced lockdown was not sustainable. However with an asset class the size of the residential property market, which now exceeds $1.54Tn and remains attractive due to still-low interest rates, any slowdown was destined to be gradual.” CoreLogic’s NZ Head of Research Nick Goodall.

Hanging tough - The Reserve Bank of Australia surprised markets and economists by sticking to its plan announced last month to ‘taper’ its money printing and bond buying programme down to A$4b/week in early September from A$5b currently. The RBA announced in its monthly monetary policy decision late yesterday it would keep its official cash rate at 0.1% despite the latest delta variant lockdowns, saying it expected a quick bounce-back.

“The experience to date has been that once virus outbreaks are contained, the economy bounces back quickly. Prior to the current virus outbreaks, the Australian economy had considerable momentum and it is still expected to grow strongly again next year. The economy is benefiting from significant additional policy support and the vaccination program will also assist with the recovery.” RBA Governor Philip Lowe.

The Aussie dollar jumped in response and market expectations of a rate hike from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in two weeks time firmed slightly last night. Interestingly for us, the RBA assumed Australia’s borders would remain closed until mid-2022.

Borders closed - In more fresh signs Australia’s economy is slowing under the weight of delta lockdowns, Qantas announced it would stand down 2,500 workers for two months because it believes New South Wales’ borders were unlikely to open before the end of October. They will stop being paid from the end of August.

Scoops and news breaking this morning

Signs’ o the times news

Useful longer reads

A fun thing

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Share this post