TLDR & TLDL: The RMA repeal and replace process has formally started, but the core problems blocking housing development have not been resolved and will dash the hopes of those hoping for a supply shock to bring affordability without being dealt with first.

Those unresolved questions are:

The Government hasn’t sought and received permission of the property-owning ratepayers who control councils to grow the population quickly, and hasn’t addressed the issue of population growth in its overall planning and funding systems in its RMA reform map;

It hasn’t resolved with those ratepayers, councils and taxpayers more broadly who will pay to build and run the infrastructure to cope with that population growth and how it will be paid for;

It hasn’t got agreement with either iwi or taxpayers and ratepayers in general about how the principles of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi will be included in these reforms in a meaningful way (ie how iwi will participate in plans and decisions)

In particular, it hasn’t reached a settlement between farmers, power generators and iwi about how to allocate and manage water rights.

My view: Repealing and replacing the RMA without properly addressing and finding a political consensus about how quickly we want the population to grow and who should pay for it is effectively putting the cart before the horse and ordering the horse to push. Repealing and replacing the RMA without dealing the key issue of iwi participation in both the new National Planning Framework and the new spatial plans is also arse about face. The lack of a conclusion on water risks stopping RMA reform on its own.

This Newshub report detailing Whangarei District Council’s reluctance to sign up to Three Waters and Clutha Council’s criticisms show the pressure is building.

My view: It’s a mistake to forge ahead with RMA reform before agreeing the Three Waters carve-up and the necessary shift to giving more revenue raising powers and higher debt limits to councils. The risk is the RMA is replaced with three acts that are an even more effective way for council planning departments to block growth surrepticiously on behalf of the property-owning ratepayers who are doing very nicely out of high population growth without the infrastructure to make it work.

‘Sticky’ councils drive house price inflation when population surges

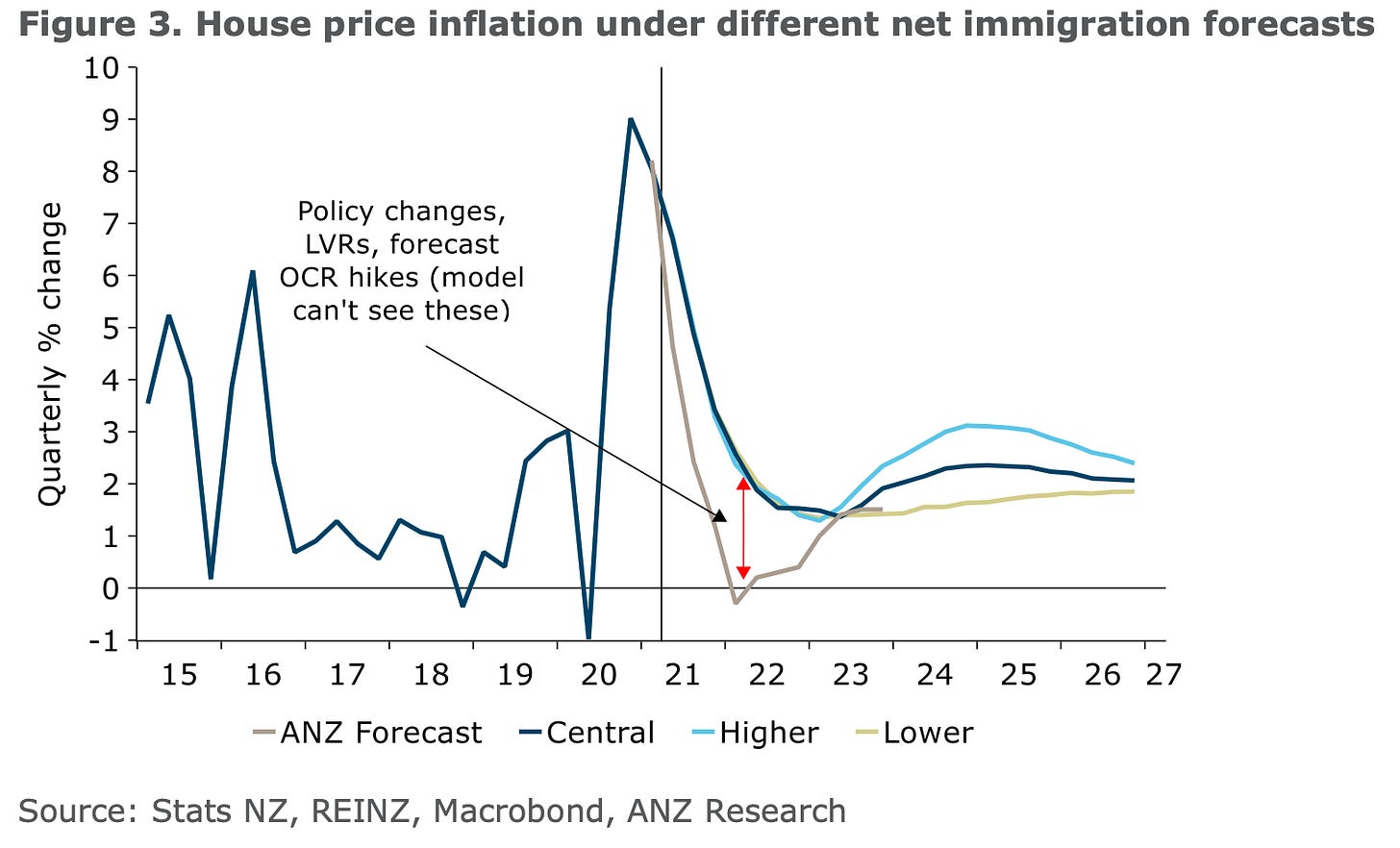

The best illustration of this came out yesterday in a research note from ANZ’s economists showing from their modelling that higher immigration is associated with surges in house price inflation and nominal GDP, but not per-capita GDP. Its modelling suggested a return to pre-Covid levels of net migration (14,000 per quarter) would double house prices again in the next five years, while lower levels of migration (6,000 per quarter) would increase house prices by almost three quarters, with all other factors being held constant.

“Focusing on the different scenarios, annualised house price inflation peaks at about 13% in the high scenario (a total increase of 99% over 5 years) and 7.5% in the low immigration scenario (a total increase of 72% over 5 years),” ANZ wrote.

“Those cumulative numbers sound massive, but they’re well-within historical experiences. For example, house prices increased 57% in the five years to May 2021, and 98% in the five years to June 2007.”

Here’s the chart.

What happened yesterday

Environment Minister David Parker formally kicked off the repeal and replacement process for the Resource Management Act process yesterday, but cautioned it would not create housing supply any time soon.

He said it was as much about producing culture change in council planning departments, some of which he described as bigger than some Government departments.

Parker released the exposure draft of the Natural and Built Environments Bill, which is first of three bills to replace the RMA and the first he hopes to pass before this Parliamentary term ends in late 2023. The other two include the Strategic Planning Act, which Parker also hopes to pass this term, and the Climate Change Adaptation Act, which is less likely to be law in this term. Parker said the first two were needed in tandem to operate together.

The NBA aims to reduce the number of district plans from 100 to around 14 and will undergo a ‘dry run’ through a select committee to iron out the kinks before a more formal select committee process after the bill is read for the first time.

Councils are grumpy to start with

This is all happening in tandem with the Three Waters reform process, which is at an even more delicate stage. More details are due later today on how three to five new larger water authorities would be created and what assets they would include. Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta hopes to get councils to sign up voluntarily with the help of $791m of carrots to help them deal with water asset problems. But she also holds a big stick in her back pocket of legislation to force the reforms through if necessary. As if that’s not enough, Mahuta has also kicked off a formal review of Local Government Funding and Governance.

All this emphasises the main problems the RMA, Three Waters and Local Government reform face: a lack of trust between central and local Government over who should hold the purse strings and benefit from economic growth, a massive financial power imbalance in favour of the Beehive, and a fundamental disconnect between the aims of the Government and the desires of ratepayers who vote.

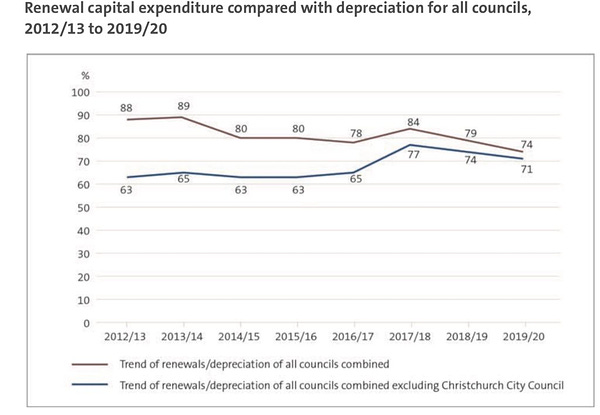

Those voters don’t want change or high council debt or higher rates or population growth, but the Government has forced these things on councils because of its own reluctance to either ask for permission for very fast population growth, or to properly fund that infrastructure. That has not changed. See the chart of the day below to see how councils have systematically invested less than they recorded in depreciation.

No successful reform without trust

The Government still doesn’t trust councils, as shown by its National-Government-like creation of a fund last week to dole out bits and pieces of money to councils for housing infrastructure. National’s fund was for loans and Labour’s is for grants, but neither are very useful for councils because they don’t address the key issue of how to fund the operational expenditure on the infrastructure when its built. Unlike in almost all other countries, our Government does not share GST or income tax with councils.

The Government is also reluctant to pay for its share of the infrastructure. That was confirmed again last month when it decided not to go ahead with the Mill Rd project in North Auckland and the Western Bays main road in Tauranga because it wanted to ‘keep a lid on debt.’ The end result is rampant population growth without the necessary infrastructure, enormous stresses on house prices, congestion and public services. Waka Kotahi’s decision earlier this month to scale back its roading maintenance and public transport spending forecasts by $420m re-emphasised the reluctance to properly fund growth, let alone try to achieve housing affordability or deal with climate change.

The risk for the Government is that ratepayers unhappy with the very big rates increases in the last year, the council-enforced shift to cycling and walking from car driving, and perceptions of a centralisation agenda that takes away local representation, will lead to ‘rates revolt’ swings to centre-right candidates in council elections next year that make it much harder for the Government to achieve its climate change and housing supply goals.

Scoops and news breaking this morning

Signs o’ the times news

Useful longer reads

Chart of the day

Share this post