TLDR & TLDL: Somewhat surprisingly, the Reserve Bank has convinced Finance Minister Grant Robertson to give it a debt to income (DTI) limiting tool to try to further slow a still fast-inflating housing market. The Reserve Bank unveiled modeling yesterday it said showed a DTI limit of six or seven would mostly hit investors and not affect first home buyers much.

The bank regulator said it would now consult with the industry, and would then need a further six months to implement it, which makes early 2023 the earliest before a DTI limit could be introduced in the normal fashion. However, Robertson still retains the option of refusing to accept it in a formal memorandum of understanding if he’s worried it actually will hit first home buyers, and the Reserve Bank could more urgently bring one in if there was another spike in house price inflation. A negative official cash rate and heavier use of the very-cheap Funding for Lending (FLP) programme of Reserve Bank loans to banks would do the trick to create a spike.

The big picture: The Reserve Bank tried to get hold of a DTI tool in the last year of the 2008-2017 Key-English Government, but then-PM Bill English blocked it because of fears it would restrict first home buyers and create the intense political pain National saw when the Reserve Bank sprung its initially-very-blunt Loan to Value Ratio surprise limits on the Government in 2013.

That LVR tool was subsequently honed to target investors more directly, but that initial pain made National Government the most vulnerable to an election loss in its entire nine years of governing, until the last minute arrival of Jacinda Ardern.

My view: The Government and the Reserve Bank don’t want to use this tool to drive house prices lower and will only ‘pull this brake’ in an emergency, and only then to slow inflation, rather than ‘pop the bubble’. They don’t think it’s a bubble. In the absence of an emergency, (ie another downturn and negative OCR + FLP), the most likely DTI limit would be set at seven, rather than six, and probably use a similar 10% of lending ‘speed limit’ to the LVR tool with exemptions for new builds.

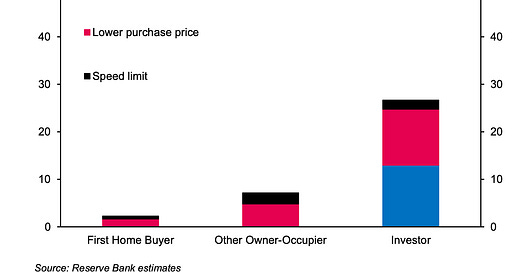

The Reserve Bank’s own modeling shows a DTI speed limit of seven would do little to drive prices lower, but would throw more sand in the wheels of investors. Here’s the Reserve Bank’s estimate of the effects: some investors would pay less and some would stop buying, while it wouldn’t hit first home buyers much at all.

The Reserve Bank said a DTI of six could reduce house prices and credit growth by two to five percent and reduce house sales volumes by around nine percent. My bet would be the Reserve Bank sets the DTI limit at seven with its first go, probably not until 2023, and then progressively reduce it to six in the event of another inflation outbreak.

Unaffordable housing sustainable politically

Essentially, the Government believes unaffordable housing is politically sustainable because young renters don’t matter in any electoral mathematics sense (Over 500,000 18-39 year olds didn’t vote in the last election and the majority voted for Labour and Greens anyway). The voters to listen to are older home owners in the suburbs and provinces, who are the ‘median’ voters needed to win re-election.

That’s why Labour has felt comfortable ruling out a capital gains tax in the PM’s political lifetime, ruling out a wealth tax in this electoral term, and refusing to use the Government’s very strong balance sheet to unleash the sort of housing supply shock necessary to drive prices down to create affordability within the next 50 years.

The Prime Minister reiterated late last year she saw her role as protecting the value of the main asset of most New Zealanders, and that a ‘sustainable’ level of house price inflation was around four percent per annum, which would not improve affordability back to pre-2003 levels for another 50-100 years, given income growth is barely above that level of price growth.

Unaffordable housing sustainable financially too

The Reserve Bank believes unaffordable housing is sustainable from a financial stability point of view, given it’s work over the last eight years bringing in the current LVR settings (albeit with one unfortunate pause), the potential to use a light-touch DTI limit, and its plan for higher capital requirements for banks.

The results of the Reserve Bank’s stress testing of banks from May last year showed the banks could handle (just) a 50% fall in house prices, an unemployment rate of 17.7% and a 17.7% fall in GDP (yes, same number). They had no problem at all with a scenario where unemployment rose to 9.3% and there was a 37% fall in house prices. And borrowers are under no stress at all, with the average cost of servicing a mortgage now at an all-time low of 5.8% of disposable income. Those stress tests were also done before the 30% rise in house prices since May last year, which has generated a $319b rise in home owners’ equity in the value of homes.

Home owners, the banks and the economy could easily handle a significant correction if that’s what the Reserve Bank and Government wanted from a housing affordability point of view. But neither of them want that. The Government can’t tolerate any fall, even though a 30% fall from current levels would simply take prices back to pre-Covid levels, and would not leave a bruise on the banking system.

The main problem for the Reserve Bank is that the housing market’s ‘wealth effect’ is its main monetary policy tool now, given it can’t cut rates much and banks have stopped lending to businesses for business and employment expansion, largely because businesses are cashed up and don’t want or need to invest. Remember most NZ businesses choose not to invest in R&D and capital investment because they’re better off investing spare cash with some bank leverage in more residential property. They have been able to expand in the last decade by adding more cheap workers, rather than investing in new machinery or business systems.

The Reserve Bank is also not mandated for housing affordability. As discussed yesterday, it successfully fought off Robertson’s initial attempt to insert ‘housing affordability’ into its monetary policy mandate late last year and now only has to worry about housing ‘sustainability’. Unaffordable housing is just fine, as long as it’s sustainably unaffordable, which the Reserve Bank said last month it thinks it is.

That’s best illustrated in this quote from its memo justifying the use of the DTI tool, and prioritising it over an interest-only lending restriction or even tougher LVR rules:

“The sustainable price level is not one specific number and will change as the underlying drivers change. For example, the decades-long decline in global interest rates has substantially lifted sustainable price levels as the interest cost of higher debt levels has declined. Increases in population relative to the supply or availability of housing have also lifted house prices, but slower population growth and greater house building may see sustainable prices decline in coming years.

The Reserve Bank’s financial policy tools can help address some of the challenges around housing, particularly when they relate to financial stability, but a broader response is needed to address affordability issues. For instance, the house price level may be sustainable based on fundamental drivers, even though rents may be high and deposits difficult to afford for prospective first home buyers. The Reserve Bank is supportive of the Government’s housing affordability goals and intends to engage constructively in policy conversations on housing affordability as well as the narrower and different question of house price sustainability.” Reserve Bank

The bolding is mine.

Fed slightly more hawkish, but only slightly

The US Federal Reserve announced this morning its Monetary Policy Committee now saw it would have to start increasing its official cash rate from near-zero percent from 2023, which was a year earlier than it had forecast back in May. It said the better Covid-19 situation meant it now saw slightly stronger growth and a slightly higher burst in inflation, but that it still thought it would be temporary.

Financial markets sold off on fears higher interest rates would slow economic growth and reduce leveraged demand for shares, but it was only a 0.5% fall in the S&P 500 and the 10 Year US Treasury yield rose around 10 basis points to an intra-day high of 1.59%, but it remains well below the March high of 1.77%.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell was quick to reassure investors the world’s biggest central bank wouldn’t pull the trigger prematurely, and still wanted to see the ‘whites of the eye’s’ of inflation being permanently higher. The Fed kept its QE or money printing running at US$120b a month and Powell decribed this month’s committee meeting as the “talking-about-talking-about meeting” on the issue of tapering down the Fed’s bond buying.

“Whenever liftoff comes, policy will remain highly accommodative. Discussing liftoff now would be highly premature. (The economy) is not out of the woods at this point and it would premature to declare victory. Our expectation is that these high inflation readings that we’re seeing now will start to abate.” US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

The famous ‘dot plot’ showing when committee members saw America’s version of the OCR over the next three years showed In March, seven out of 18 committee members predicted the first interest rate increase would be in 2023, while 13 saw the first hike in 2023 this month. Powell also downplayed this change in the broad view of the committee.

“The dots should be taken with a big grain of salt,” Powell said and said talking about actually raising rates was “highly premature.”

My view: The whole financial and business world is waiting with bated breath to see if the inflation surge going on now will turn into something bigger and more permanent that forces the Fed to quickly hike interest rates quite high. That would seriously destabilise the global economy and financial markets.

I’m with the Fed in thinking the CPI inflation is temporary. The deflationary smart phone engines in all our pockets are still pushing down on global wages and services inflation, and the Chinese factories pressing down on goods prices are still there, as are the workers in those factories. The ships and containers that are currently in the wrong places and frustratingly disrupted and expensive are also still there. Once they’ve got their schedules back in order and the containers are in the right place the CPI inflation genie will get back in the bottle.

Asset price inflation is an entirely different story, but central banks don’t have to put up interest rates to achieve an asset price inflation target. They are only mandated to target 2% inflation and don’t need the approval of politicians or voters to do whatever they see fit to get there. The money printers will keep humming for a long time yet.

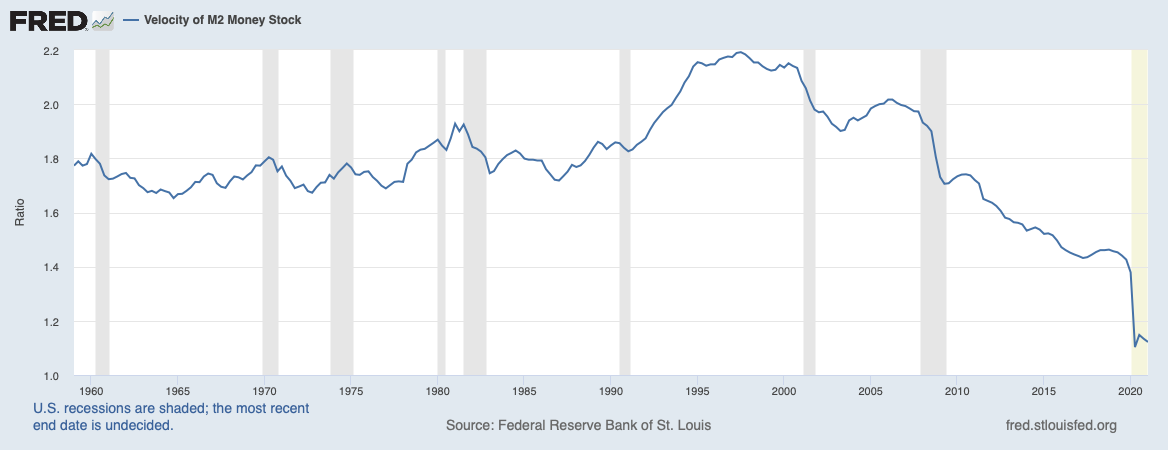

The reason the US$10t increase in money supply in the last year hasn’t caught fire as goods and services inflation is that more than half of it has been parked back in bank accounts and central bank reserves by banks, pension funds and the wealthy individuals who sold their bonds to central banks for the newly created cash. They don’t want to spend or invest the money because they’re risk averse and already have plenty of money. It’s why we’re seeing house plants sell on TradeMe for NZ$27,100 and tickets for trips to the moon with Jeff Bezos selling for US$28m a pop.

The extra money supply is circulating much more slowly than it used to because more and more of the cash is concentrated in the hands of the already-wealthy, who don’t want to or simply can’t spend or invest it. Rinse and repeat until voters take away the independence of central bankers and force Governments to share the freshly-printed money around more equally to people who need it and have an appetite to spend or invest it. This chart shows what has happened to US money supply circulation speed since 1960. It has almost halved in the last 20 years as more wealth has become concentrated in the hands of the wealthiest, who have increasingly parked it in Government bonds and bank accounts.

Signs o’ the times news

Charts of the day

Thread for unravelling

Share this post