TLDR: Hopes 16 and 17 year olds might get the vote look set to be dashed again, almost as soon as they were raised by a Supreme Court ruling yesterday that Parliament should consider lowering the voting age from 18 to avoid breaching the age discrimination provision in the Bill of Rights.

National and ACT pledged last night to vote against a Labour proposal to lower the voting age, making the required super-majority to pass it in Parliament virtually impossible without a conscience vote.

Allowing as many as an extra 125,000 people to vote could help reduce a democratic deficit that has built up in recent decades where young renters in particular vote at much lower rates than older homeowners. So far, this deficit has meant the electoral mathematics that would eventually see the centre of political power shift from the baby-boomer bulge to those aged under 50 has been delayed.

It’s a deficit most prominent at council level and cited by the Productivity Commission as a factor allowing suburban land owners to stop new land being made available for housing for the young, along with the necessary infrastructure they would have to pay for with higher taxes, public debt and rates. At general election level, it’s a deficit that helped block any sort of capital gain or wealth tax. It’s the deficit at the heart of the biggest transfer of wealth from future generations to landowners now that’s been seen in modern history. I estimate that shift at over $1 trillion in the last decade.

The old and rich are opting to block the young from voting to reverse the wealth transfer.

But there may be some hope to reduce the deficit at a local level, given a super-majority is not needed to lower the voting age at council level, while a super-majority is needed at general election level.

Paying subscribers can see more detail and analysis below the paywall fold, although I’ve also included a poll below to ask paying subscribers if I should open it up for public viewing and listening by lunchtime. Update: This has now been opened up and can be shared.

A new generation’s opportunity

For a few hours yesterday there was some hope of a boost in political power for new generations wanting to rectify a monumental wealth shift to the older generations that politicians must now keep happy to win.

Te Koti Mana Nui o Aotearoa (The Supreme Court) ruled early in the afternoon in favour of the ‘Make it 16’ case that not allowing 16 and 17-year olds to vote was inconsistent with the Bill of Rights banning discrimination on the basis of age.

PM Jacinda Ardern announced in her post-Cabinet news conference yesterday afternoon after a discussion in the Cabinet meeting that Labour would draft legislation in response to the court ruling to lower the voting age to 16 from 18. Electoral Law requires a response from the Government in Parliament within six months of the Supreme Court ruling being notified to a select committee. She noted that even if passed under the required 75% super-majority, the law change would not be in place until the 2026 election at the earliest.

Ardern said Labour’s caucus did not have a position and she hoped it would be opened up for a conscience vote. She supported lowering the voting age.

“This is a matter where I hope parties feel that they're able to have an open debate and discussion that isn't based on politics, but on their own values and principles.” Jacinda Ardern (post-Cabinet news conference transcript)

The Greens supported lowering the voting age too, but National and ACT came out immediately in opposition. ACT Leader David Seymour said it wouldn’t happen and appeared to suggest ACT believed only taxpayers should have the franchise to vote.

“We don’t want 120,000 more voters who pay no tax voting for lots more spending. The Supreme Court needs to stick to its knitting and quit the judicial activism.

“My proposition to 16 and 17 year old voters is this. There’s only a two out of three chance that you’ll get an extra vote out of this, but you will pay extra tax for whatever crazy thing 16 and 17 year olds voted for at the last election.” David Seymour in a statement.

Statistics NZ figures for the September quarter show there were 145,300 people aged 15-19 who worked and presumably were paid wages and therefore paid taxes in the quarter. That was up from 126,600 working in the same quarter a year ago. I suspect there’s a few 16 and 17-year olds who also pay GST on their purchases. Statistics NZ figures also show an estimated 125,700 16 and 17 year olds were resident in Aotearoa as at the September quarter. If they all voted (see more on that below) that would be enough to change the result of an exceptionally tight election, if they voted one way or another.

National’s Justice Spokesman Paul Goldsmith said National didn’t support lowering the voting age. He said cracking down on youth crime was more important.

“Many other countries have a voting age of 18, and National has seen no compelling case to lower the age.”

“With violent crime up by 21% per cent, a 50% increase in gang membership and a 500% increase in ram-raids, these are pressing matters the Labour Government are failing to get under control. That is why National announced its plan to crack down on serious repeat youth offenders like ram-raiders to turn their lives around and to protect the public.” Paul Goldsmith in a statement.

His leader also said 16 was too young to vote.

"Obviously, we've got to draw a line somewhere. We're comfortable with the line being 18. Lots of different countries have different places where the line's drawn and from our point of view, 18's just fine." National Leader Christopher Luxon told reporters in Napier yesterday. 1News

So why does it matter if the age drops to 16?

Here’s the key chart that explains the problem of the democratic deficit from Electoral Commission data. It shows voting rates of the eligible population by age group for the last three general elections.

From the ages of 18 to 39, there are over 280,000 people who could have voted in the 2020 election if they had voted at the same 85% rate as those over the age of 50. This number of missing voters was down substantially from the 2017 and 2014 elections because of an increase in enrolment rates and voting rates, but there remains a hole in democratic representation by age which is delaying the eventual transfer of power from the baby boomers to those who follow. Lowering the voting age would accelerate that. Assuming the younger 16-17 year olds voted at the same rate as those over 50 in 2020, that would imply an extra 106,845 voters. Adding the ‘missing’ voters from 18-39 creates a potential extra voting pool of nearly half a million.

The yawning democratic deficit at council level

The gap is even larger at local council level, as this chart of voting by age group and ethnicity from Auckland Council’s 2017 election results shows.

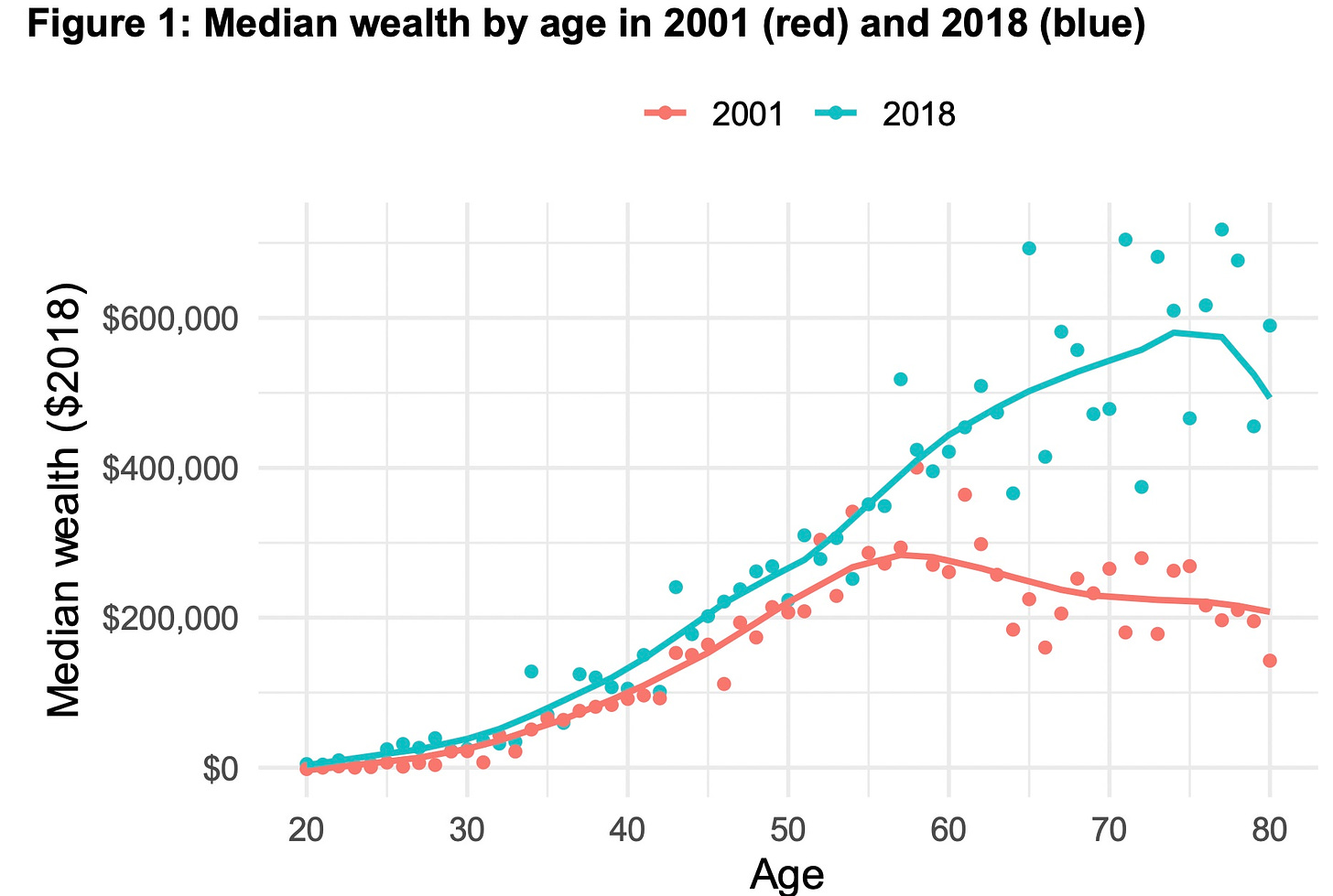

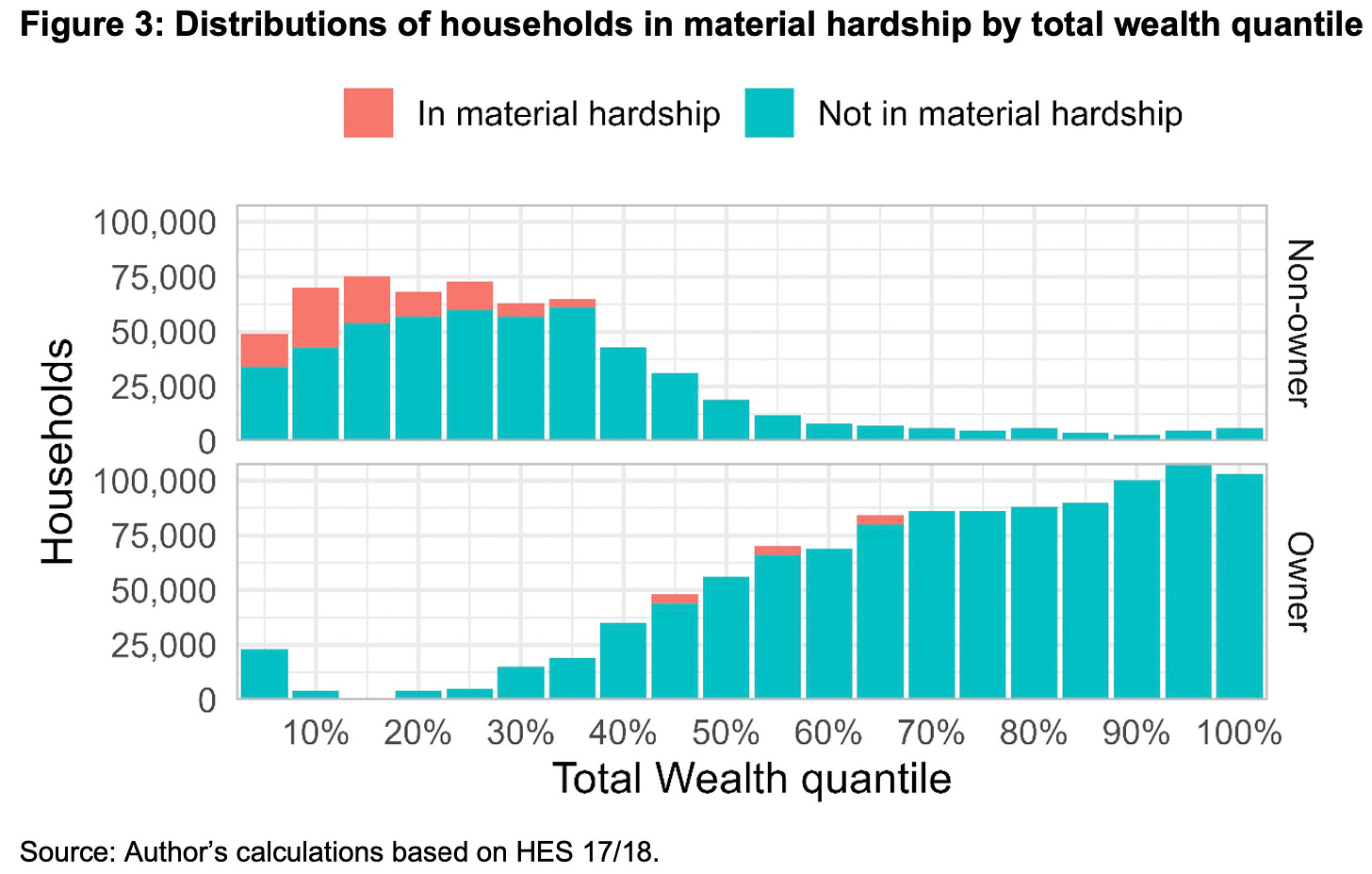

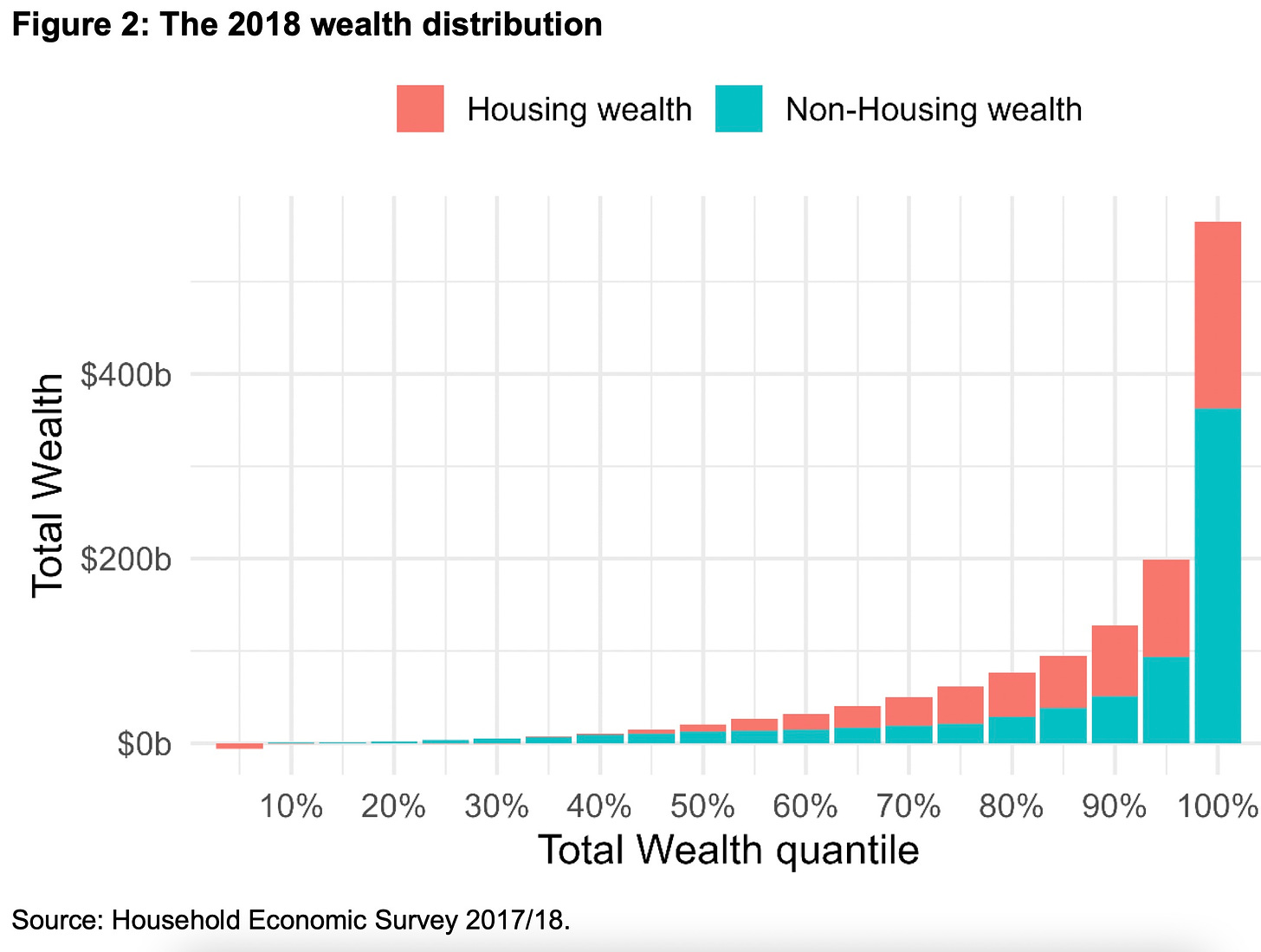

The scale of the wealth transfer from the young to the old is even clearer, once the effects of the housing boom’s increase in net worth over the last 20 years is taken into account. It accelerated dramatically during covid, especially for young renters, as these three charts show. The shift is at least $1 trillion from lower age groups to older age groups in the last 20 years. Here’s the way it changed between 2001 and 2018. It will have worsened since then.

But there is a chance for council elections

The 75% super-majority requirement may block change at the general election level, but the franchise could be lowered to 16 for local elections, as the recent Future of Local Government Review suggested should happen in its draft report. The Local Electoral Act can be changed with a simple majority, unlike the Electoral Act.

Labour’s caucus has yet to express a view on the local vs general ages, but Ardern agreed in the news conference it was possible Parliament could vote differently on local vs general.

So how is the hegemony of older landowners enforced?

The concept of the democratic deficit as a political economy problem was well outlined by the Productivity Commission in its ‘Housing Affordability’ inquiry of 2012, its ‘Using land for housing’ inquiry of 2015 and its ‘Better Urban Planning’ inquiry of 2017. It is summarised here in this February 2020 note: (bolding mine).

“Homeowners have considerable influence in local body elections and are often strongly represented in community consultation processes. Their influence promotes council decisions that restrict urban intensification and the supply of new land for housing.

“By contrast, those bearing the negative outcomes of councils’ planning and funding decisions are not well represented in either community engagement or local elections. People who tend to be underrepresented include those who are younger (particularly those aged under 25), Māori, Pasifika, and renters – groups more likely to suffer from a lack of affordable housing.

“All this is contributing to a democratic deficit, meaning some people’s views and interests are not adequately represented and councils are not being adequately held to account for the impacts of their decisions.” Productivity Commission note

It’s the same at national level

This skewing of the electoral power to those aged over 50 has been reflected repeatedly over the last 10-20 years in the policy choices made via electoral results, and more importantly, by the policy choices not even presented by either of the main parties at elections.

The classic example of that is the Capital Gains Tax, which benefits those owning leveraged residential land at the expense of future and current renters, particularly those with aspirations of ownership. It has been the core point of debate at the 2011, 2014 and 2017 election. Its absence at the 2020 election because Ardern declared in 2019 she would never (in her political lifetime) propose one again, was effectively endorsed by Labour’s election win. The 2017 and 2020 results also reinforced Labour’s policy change to not increasing the age of eligibility for NZ Superannuation.

The electoral mathematics that reward policies aimed at median voters, who are still mostly older suburban and provincial homeowners, have made it impossible to try to either stop the shift of wealth from the young to the old, or to try to reverse it.

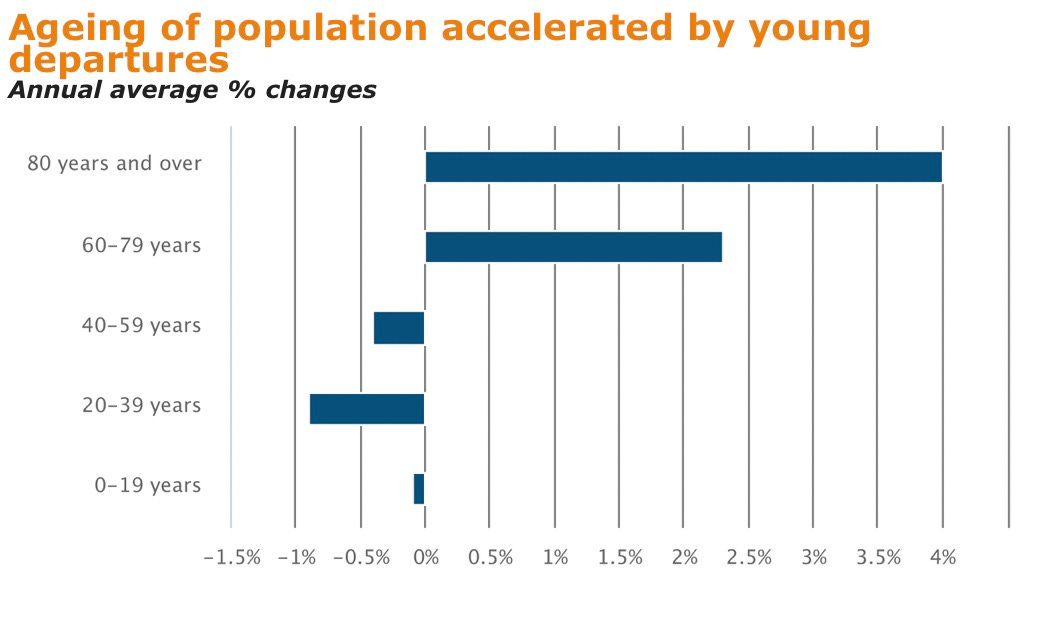

The improvement in voting rates is slowly turning the tide, along with the demise of some of those voters, but there are headwinds to that tide, including the increasing tendency of younger residents to give up and migrate permanently in their 20s. That’s at least in part because of high house buying costs, along with the inability to save for a housing deposit because of high rents relative to incomes.

This chart via Infometrics shows an ageing population as the young leave. More than 50,000 residents in their 20s have migrated permanently since the borders opened this year.

Teach it in schools to improve the habit

Lowering the voting age would push back against that outgoing tide, and potentially lift turnout rates permanently as those voters age into their 20s and 30s, as University of Waikato lecturer Nick Munn pointed out in 2020 via The Conversation.

“Importantly for the long-term health of our democracy, once very young voters have voted, they are more likely to continue voting than those who couldn’t until they were 18.

“Lowering the voting age may, in fact, benefit turnout. Voting is a habit which, once formed, is harder to break. If 16-year-olds have the desire but not the opportunity to vote, by the time they can, some percentage of them has become disengaged.” University of Waikato lecturer Nick Munn pointed out in 2020 via The Conversation.

The potential for civics education to involve a ‘real-life’ exercise of training young people to vote while in their last year or two of high school is also appealing.

Although not for all, including the likes of former Auckland Mayoral candidate Leo Molloy, who tweeted the following yesterday (bolding mine).

“My view on 16 y’olds voting, as a father of 5 aged between 15&21, it seems fine at face value however secondary school teachers and university lecturers are invariably quite left leaning and they brainwash kids around social issues which precludes sound rational voting, JMHO.” Malloy via twitter.

That is the real issue here, at least in a perceived sense. Older, richer voters know that widening the franchise to include younger voters and increase the turnout of those who don’t own land would create the risk of policies that reverse the historic shift in wealth from the young to the old.

The old and rich are opting to block the young from voting to reverse the wealth transfer.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Share this post