TLDR: 2022 was the year two global supply shocks — covid-driven worker shortages and the Ukraine war’s hit to gas and oil supplies — put a blowtorch under inflation already simmering because of plenty of Government spending and monetary stimulus to combat covid in 2020 and 2021.

That led to an aggressive response from independent inflation-targeting central banks trying to win back their inflation-fighting credibility and jump down hard on consumers, workers and employers who might be starting to raise their inflation expectations. Those central banks, including our own, were forced to use a short-term demand management tool, higher interest rates, to respond the effects of what now appear to be two long-term supply shocks.

But what other choices do we have? One way to respond to supply shocks is to shock supply right back up again with increases in productive capacity, which could include:

more investment in public infrastructure to increase the productive capacity (output per hours worked) of workers, businesses and the arms of Government;

investment in public health and education to improve both the number and quality of the hours those workers dedicate to work;

increasing research and development from both the private sector and public sector;

encouraging deeper integration with the global economy by increasing the share of the economy competing overseas firms and increasing the amount of overseas investment in local businesses; and,

changing tax rules and public incentives to invest more in businesses and infrastructure that increase the productive capacity of the economy per hour worked.

The Government’s main adviser on improving the productive capacity of the economy and society overall is the Productivity Commission. Just as the short-term policy makers, the Treasury and the Reserve Bank, have had a big year, so has the Productivity Commission.

I talked with Commission Chair Ganesh Nana just before the summer break about this issue of productive capacity, including the Commission’s work this year on;

starting a new inquiry into the resilience of Aotearoa’s supply chains;

following up its 2020/21 inquiry into ‘Frontier Firms’ that compete internationally with a review of the Government policy response to that inquiry;

delivering its draft report on its ‘Fair Chance for All’ Inquiry into persistent disadvantage; and,

delivering its final report and recommendations into our long-term immigration settings.

Where’s the long-run supply response?

We got to talking about the big inflation dramas this year and the response from the holders of the levers of short-term fiscal and monetary policy. Nana said he’d like to see the inflation shocks seen within a longer-term context of constrained productive capacity and the brittleness now evident in parts of society and the economy, which worsen those long-run supply issues.

“If we’re serious about productivity, we should be looking for long-term solutions and framing it in the long-term context.

“For example, in our frontier firms inquiry, in terms of our immigration inquiry, the recommendations are very much in terms of long-term. That whatever immigration policy we might choose, it has to be framed along with the long term infrastructure investment needs.

“And where is the plan for that alongside the plan for immigration? Similarly, frontier firms, if we're serious about productivity, where is the investment in science and R & D, in workforce development and investment in our social infrastructure, in terms of social cohesion.

“Covid reinforced just how important our social cohesion is.” Ganesh Nana.

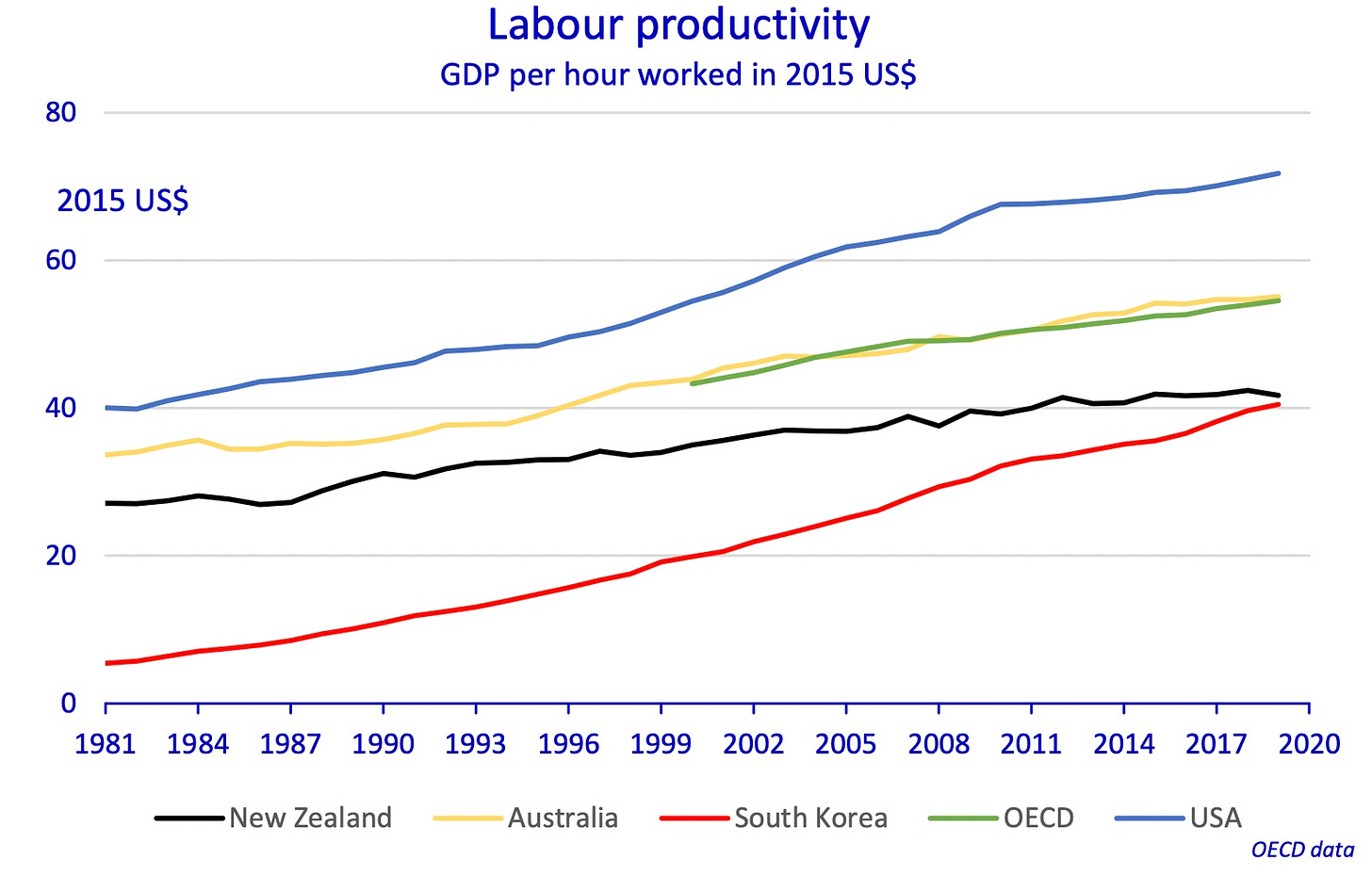

He pointed in particular to Aotearoa’s long-running history of under-investment in infrastructure and R&D, leading to a stagnation in output per hour worked relative to our OECD peers from 20-30 years ago.

The exception that proves the rule

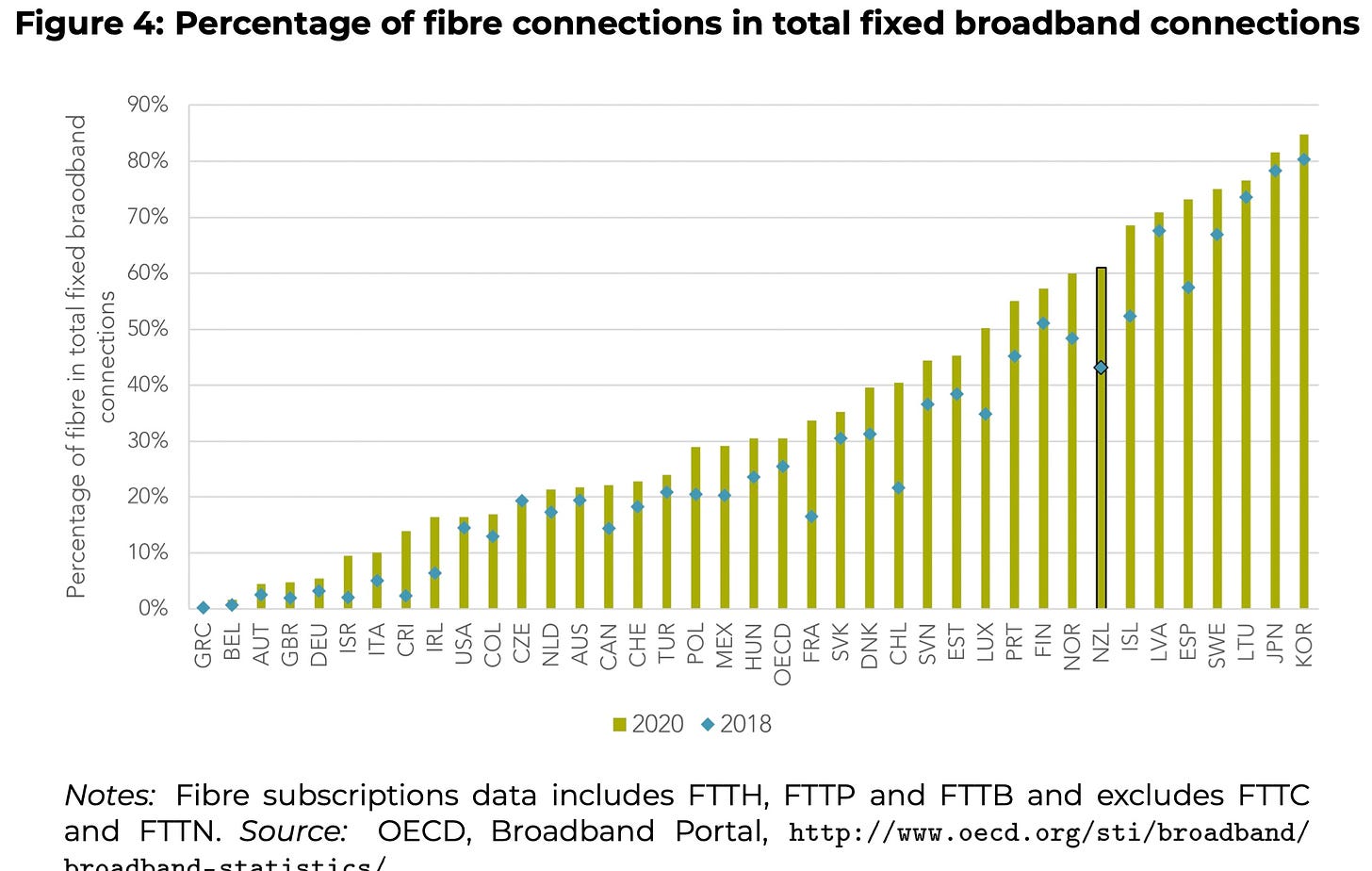

I raised the one recent example where the Government used its balance sheet to invest public funds in infrastructure that improved productivity. The previous National Government invested almost $2 billion in public funds to roll out Ultra Fast Broadband optic fibre and wireless networks to 1.8 million homes and businesses in 412 cities and towns covering 87% of the population.

The Productivity Commission has just completed research that found the roll out of UFB boosted the ability and willingness of businesses to export, which previous research has shown improves the competitiveness, scale and international connections that boost productivity.

The subsidised UFB rollout means the proportion of high-speed internet connections in Aotearoa is nearer the top half of the OECD, rather than the bottom half, where Australia and the United States reside, as this OECD chart in the research shows.

“This paper finds that early adoption of high-speed fibre internet is a predictor of future export entry by New Zealand firms. Controlling for other observable characteristics and looking across export industries as a whole, firms which took up fibre broadband connections in the early stages of the UFB rollout were between 5 and 12 percentage points more likely to enter exporting over the following two years than other (non-fibre) broadband users.” Productivity Commission paper.

Both bricks and mortar and R&D needed to lift productive capacity

This year’s major report by the Infrastructure Commission in May illustrated the scale of our infrastructure deficit ($109 billion) and the likely requirement for another $100 billion of investment over the next 30 years to keep up with even half the population growth we’ve seen in the last decade. Currently, the Government has plans for just over $50 billion of public investment in ‘bricks and mortar’ for housing, water, roads, rail, schools and hospitals over the next five years. The Commission said the Government would have to double its infrastructure investment from 5% of GDP annually to 10% to be able to ‘build its way’ out of the hole.

In May this year, Finance Minister Grant Robertson rejected the Commission’s suggestion $200 billion would have to be raised and invested, saying taxpayers could not afford and did not want the higher taxes and public debt it implied. He suggested the gap could be filled by more congestion charging and other demand management measures, along with restricting population growth through migration by limiting worker migration to higher skilled and higher paid migrants. The Government has yet to respond to the Productivity Commission’s separate recommendation it develop a cross-party and cross-election-cycle migration plan that first worked out what the capacity of existing infrastructure was to absorb more population growth. The Government has since shied away from any discussion of planning migration levels. It abandoned its residency planning range in October.

Since then, the Government has shied away from committing to congestion charges, which most Mayors also reject, and it has announced three loosenings of migration settings to allow more and more migrant workers to come and be paid at relatively lower wages than under the original settings in May.

Invest more and consume less to cut inflation, in the short and long run

Nana said the long-run record of under-investment was a factor in the pressures on supply. Increasing investment would both take pressure off inflation through relatively lower consumer spending and increasing supply,

“Whether you talk about our investment in R&D or whether you talk about investment in the bricks and mortar, as per the Infrastructure Commission, it does signal that we need to scale that effort up a lot more, and that goes very consistently with the argument about fighting inflation.

“If you're serious about fighting inflation, we need to take the heat out of the consumption basket and put it in the investment basket. We haven't got the tools. Monetary policy doesn't do that well because monetary policy just slams down on investment across the board.

“It hurts investment and exporters a lot more than it hurts consumers. So we need another lever or another tool to actually shift that demand. But I'm not overly keen on taking demand out of the system. I'd like to to shift that demand away from consumers, away from me going out there and buying the best and brightest and more towards businesses to invest in innovation and develop exports that will see us through, not just to the next supply shock, but see us through the next couple of generations.

“That’s the shift that we need within if we’re serious about responding to the lessons from covid.” Ganesh Nana in the interview above.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Why are we using a blunt and short-term demand lever in response to two long-run supply shocks?