Long stories short, here’s the top six news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa this week, and a discussion above between Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer:

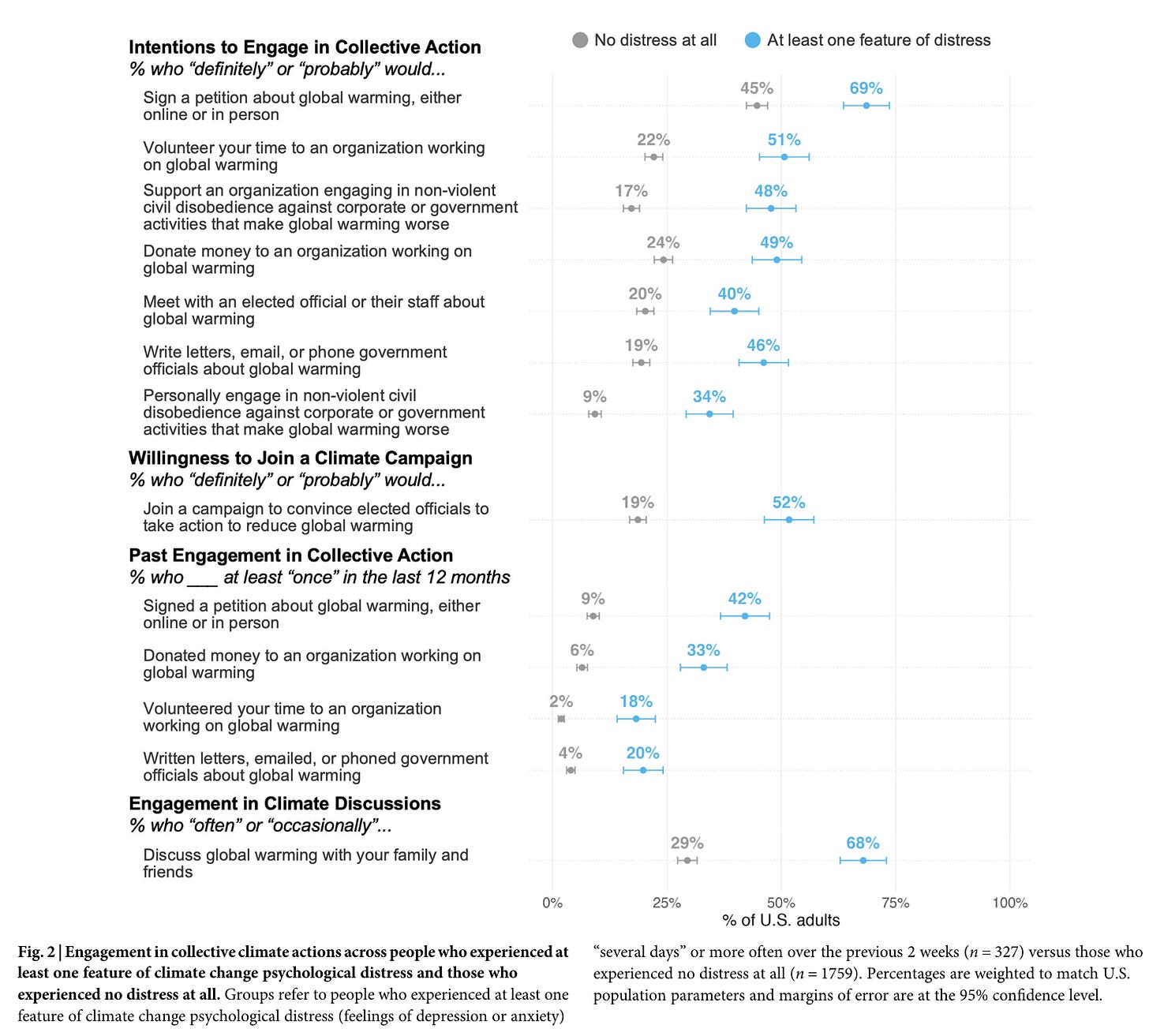

A study looking at psychological distress associated with climate change has stimulated discussion about the insistent demands for ‘hope’ and ‘positivity’ in climate communications. The study found that those suffering from higher levels of psychological distress were also more likely to be engaged in collective action to address climate change.

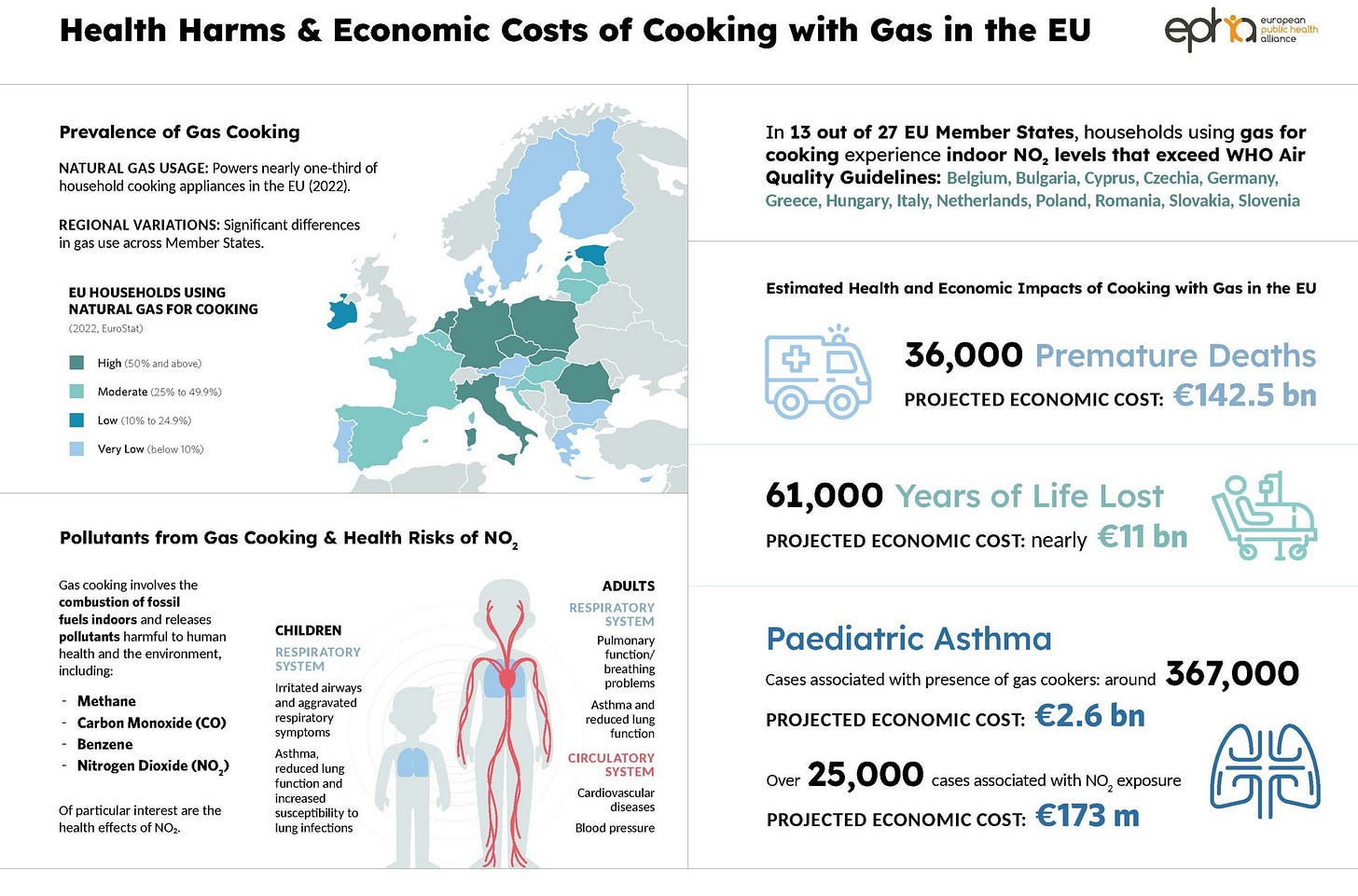

A new report on the health impacts of indoor pollution from gas stoves in the EU has found the lifespan of people cooking on gas stoves is reduced by two years on average.

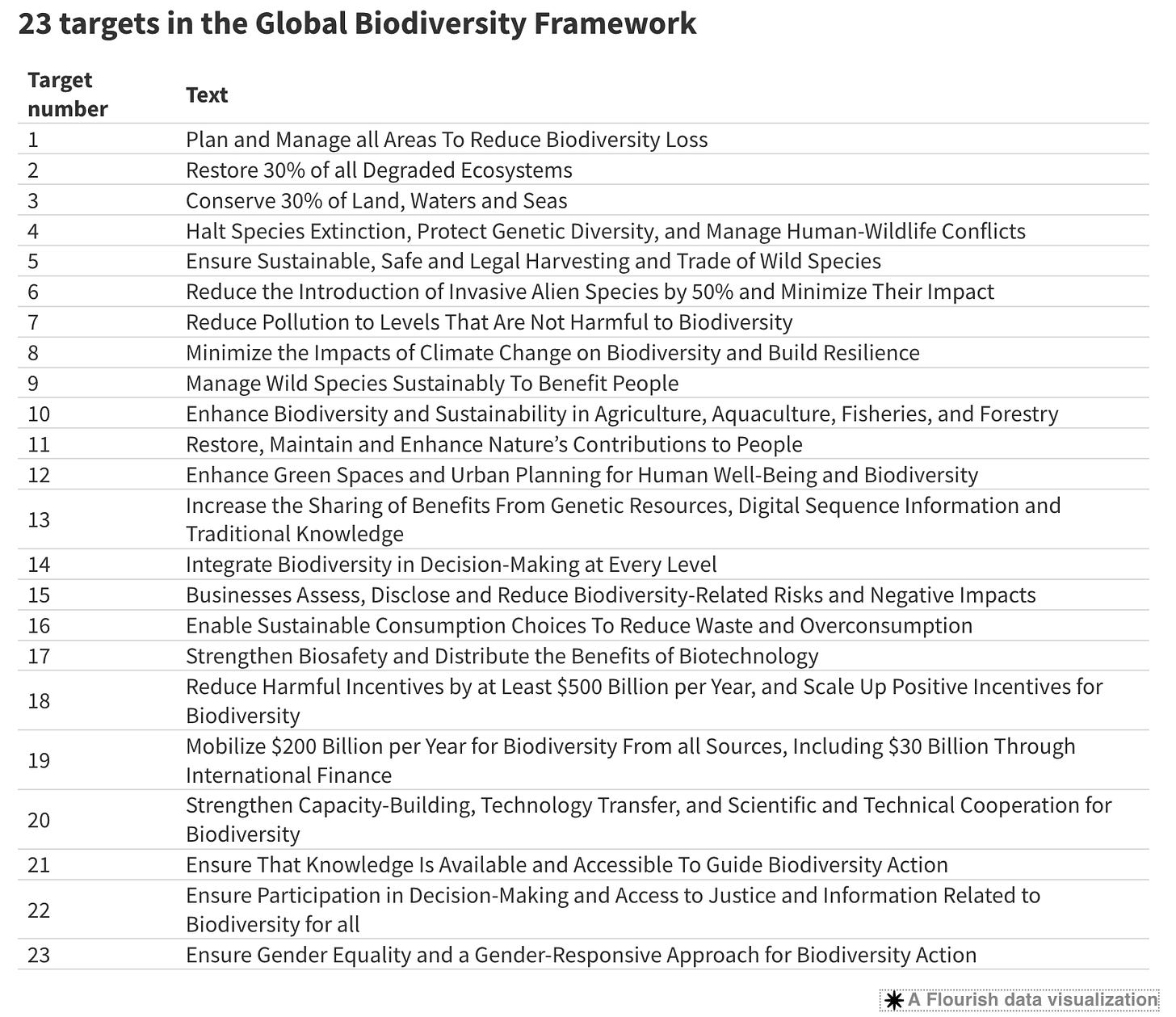

Research has shown biodiversity is declining even faster in protected areas than elsewhere. Scientists analysing the ‘Biodiversity Intactness Index’ ahead of the 16th Global Biodiversity COP, opening this week in Colombia, have warned that just designating areas as protected is not sufficient.

Environmental advocates have accused the New Zealand Government of ‘waffling’ in response to the biodiversity crisis. They say the Government is turning up to the Biodiversity Conference in Colombia this week with no real plan or policies to achieve the targets in the Framework Agreement.

A group of leading climate scientists from nine countries have signed a pledge calling for ‘real zero’ not ‘net zero’. They say that corporate offsetting does nothing except hinder the energy transition.

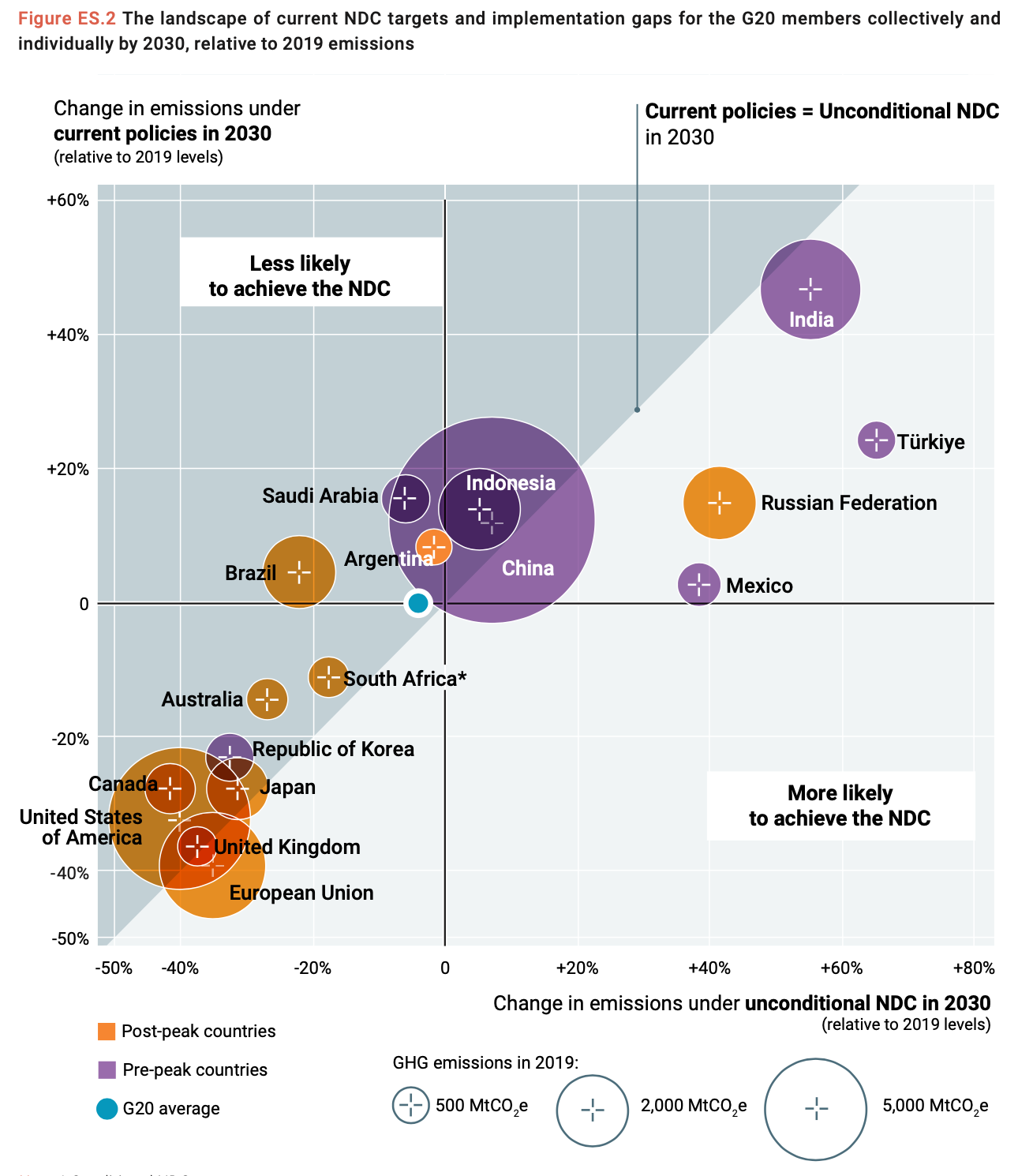

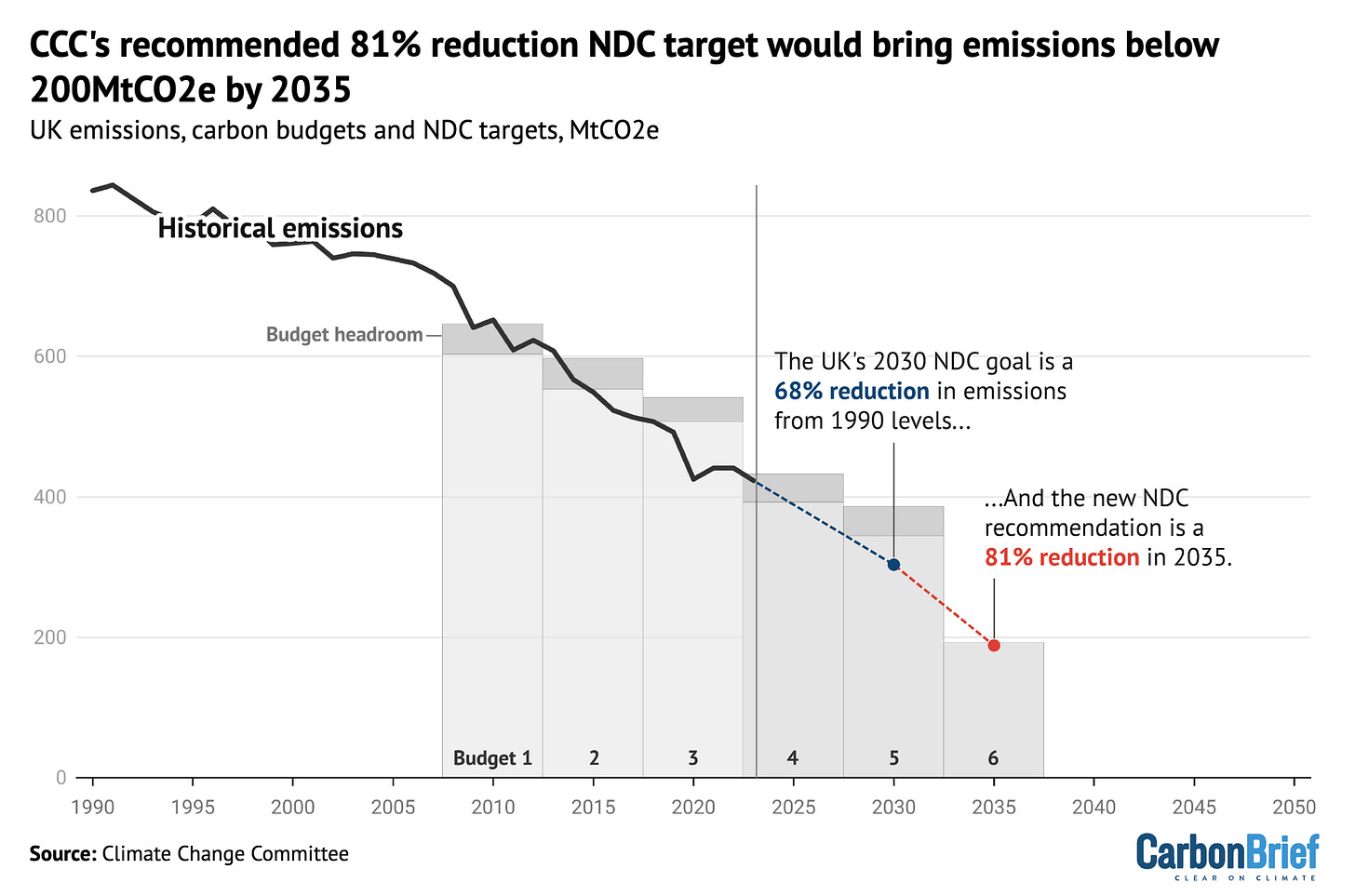

The chart of the week comes from the 2024 UNEP Emissions Gap Report and shows how many G20 countries are on track to achieve their 2030 NDC targets (not many). It comes in the same week that the UK’s Climate Change Commission recommends even steeper cuts of 81% by 2035 for their seventh carbon budget, despite a paucity of policies keeping the country on-track for its 2030 target.

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the video and podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

1. The risk of creating ‘comfortable numbness’ over climate

A study in the journal Nature has kicked off a conversation about the potential harms of ‘toxic positivity’ as communicators are relentlessly urged to promote ‘hope’ when talking about climate change.

The analysis showed that the relationship between climate-related psychological distress and four measured climate action outcomes is both positive and significant.

The study also found that those groups most likely to experience psychological distress from climate change are those most vulnerable and exposed to the effects of it, including communities of colour, indigenous peoples, low income communities and younger people. These also happen to be the groups that have historically been the key leaders in environmental movements. The report recommends that

“While climate change psychological distress may motivate engagement in climate action, which in turn may help some people cope, it is essential that people experiencing distress have access to effective mental health resources and support7. Building accessible and climate-informed mental health services is important to helping people cope, promoting positive engagement with climate change, and strengthening adaptive resilience and overall well-being in the face of these challenges.” Nature

The study results are in tune with a growing conversation about the relentless positivity urged by some activists and climate leaders. In an op-ed in The Guardian, Jonathan Watts, questions the incessant promotion of “hope” by leaders, suggesting that it is contributing to a ‘comfortable numbness’ that curtails action.

“New research reveals that people who are experiencing climate-related distress are more likely to engage in collective action. History, by contrast, shows that manufactured optimism can lead to complacency and the shirking of responsibilities.

In the 1990s, hope – coupled with doubt – was the fossil fuel industry’s antidote to the precautionary principle, the sensible idea that some problems had such dire implications that humanity should err on the side of caution even if the science was not completely settled. When George Bush was president, he was initially so concerned by the impact of fossil fuels on the climate that he looked into regulating the oil industry. But he backed away from this on the grounds that future generations would probably develop new technologies to solve the problem. Call that dumb, call that wishful thinking, or call that hope, the result was the same: no action.

That once again looks to be the temptation of Britain’s Labour government in promising £22bn for carbon capture and storage projects. This technology is supposed to catch greenhouse gas emissions before they can enter the atmosphere. But it is incredibly expensive, has never worked at the necessary scale and, until now, has largely been a ruse for the petroleum industry to continue pumping.

Amy Westervelt of Drilled Media also recently discussed the “unsettling disconnect between people noshing on passed hors d'oeuvres and sipping craft cocktails while talking about the need to "stay positive!" "tell the positive stories!" "give people hope!" and the reality crashing in all around us”, in a newsletter following New York’s climate week.

“Don't get me wrong, there are good news stories and I know how important it is to share and savor them, but the focus on positivity to the exclusion of anything else felt completely surreal and, if I'm being honest, a little scary. It reminded me of something I've heard climate psychologist Renee Lertzman say repeatedly over the years, that the climate crisis is a trauma that needs to be processed, and of what trauma specialist Thomas Hübl calls "collective numbness," that thing that happens when people tacitly agree to leave the trauma lingering, unprocessed, below the surface.” Drilled

Part of that reality is that the repeated ‘tone-deaf’ calls for positivity can be a sign of privilege and carbon colonialism that ignores the pain already being experienced by the most climate vulnerable groups on the frontline of climate impacts. As Westervelt eloquently puts it:

“... over and over again in rooms teeming with white Global Northerners, I heard earnest pleas to center the voices of the Global South. It was a real "actions speak louder than words" kinda week for me. You want positive stories? Take the action required to generate real improvement and stop over-hyping incrementalism! You want to knock disinformation on its head? Fund investigative journalism! You want to center Global South voices? The bodies those voices inhabit need to be in the dang room!” Drilled

2. Using a gas stove shaves 2 years off a person’s life

A new report from the European Public Health Alliance proposes policy solutions after a Health Impact Assessment found at least 40,000 premature deaths in Europe related to nitrogen dioxide from gas cooking. The death toll is twice as high as that from car crashes.

“The cookers spew harmful gases linked to heart and lung disease but experts warn there is little public awareness of their dangers. On average, using a gas stove shaves nearly two years off a person’s life, according to a study of households in the EU and UK.

“The extent of the problem is far worse than we thought,” said lead author Juana María Delgado-Saborit, who runs the environmental health research lab at Jaume I University in Spain.

The researchers attributed 36,031 early deaths each year to gas cookers in the EU, and a further 3,928 in the UK. They say their estimates are conservative because they only considered the health effects of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and not other gases such as carbon monoxide and benzene.” The Guardian

The EPHA is urging policymakers to phase out gas cookers by setting limits on indoor emissions, subsidising switching to cleaner cookers and forcing manufacturers to clearly label the pollution risks on their cookers.

The analysis follows a US study earlier this year that attributed 19,000 early mortalities there to the effects of gas stoves.

3. Protected areas of biodiversity declining even faster

Ahead of the 16th Biodiversity Conference of Parties (COP), scientists are warning that the agreement to protect 30% of land and water for nature by 2030 may not be sufficient as analysis shows that biodiversity is declining even more quickly in areas that have designated protection status.

Simply designating protected areas will not automatically assure better outcomes according to the analysis by the UK’s Natural History Museum.

“Researchers looked at a Biodiversity Intactness Index, which scores biodiversity health as a percentage in response to human pressures. The report found the index declined by 1.88 percentage points globally between 2000 and 2020. It then focused on the critical biodiversity areas that provide 90% of nature’s contributions to humanity, 22% of which is protected.

The study found that within those critical areas that were not protected, biodiversity had declined by an average of 1.9 percentage points between 2000 and 2020, and within the areas that were protected it had declined by 2.1 percentage points.

The authors say there are a few reasons why this might be the case. A lot of protected areas are not designed to preserve the whole ecosystem, but rather certain species that are of interest, which means total “biodiversity intactness” is not a priority.

Another reason is that these landscapes could have already been suffering degradation, which is why they were protected in the first place. Researchers say specific local analysis is key to working out why each one is failing.” The Guardian

4. New Zealand lacks action plan to achieve biodiversity targets

Environmental advocates claim that the government lacks a plan ahead of the global biodiversity summit being held in Colombia this week. The framework is seen as the biodiversity equivalent of the Paris Agreement for climate. Countries are expected to present their plans for achieving the 23 targets outlined in the framework by 2030. According to WWF-New Zealand chief executive Kayla Kingdon-Bebb:

“New Zealand’s rocked up with a bunch of waffle and some empty, high-level platitudes with zero financial commitment and no action plan about how these targets are going to be made manifest in our domestic policy." RNZ

The global framework’s 23 targets include:

5. Scientists argue for “real zero” not “net zero”

Scientists from nine countries, including Prof. Michael Mann, of the University of Pennsylvania, Professor Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact, and Bill Hare, founder of Climate Analytics and a member of a UN expert group, have signed the “real zero pledge”, organised by The Lethal Humidity Global Council.

The pledge claims that the “only path that can prevent further escalation of climate impacts” was “real zero” and not “net zero”. Further, they claim that carbon off-setting used by corporations are ineffectual and hindering the energy transition. Source: The Guardian

6. Chart of the week: Countries not on-track to achieve 2030 targets

Climate crunch time is here according to the UNEP Emissions Gap Report for 2024. The following chart from the report shows that 11 out of the G20 member countries are off-track to achieve their 2030 NDC pledges, and those that are on track are countries that did not strengthen, or only moderately strengthened their targets in the latest round.

“Some parts of the world are burning. Some parts are drowning and people everywhere are struggling to cope and in many cases to survive – particularly and always the poorest and most vulnerable. Against this backdrop of tragedy and rising climate anxiety, nations are preparing new climate pledges for submission early next year.”

Despite the lack of current policies to achieve the 2030 NDC target, the UK’s climate change commission has recommended even steeper cuts in territorial emissions of 81% by 2035 (from 1990), in its advice for the country’s seventh carbon budget.

Source: Carbon Brief.

Ka kite ano

Bernard and Cathrine

Share this post