TL;DR: Sea and air temperatures smashed records in 2023 and now most of the Davos crowd expect a catastrophic global climate event in the next decade. So why can’t humans organise themselves to stop one happening?

The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer begins her first weekly wrap of 2024 with a closer look at the climate records of 2023 and research showing we may be evolutionarily unfit to respond to stop climate emissions, even though we technically could. Bernard and Cathrine talk through the implications in the video above.

Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share.

2023 was the year we lived most dangerously

The year 2023 was a defining year for climate change, with surface and ocean temperature, along with sea ice extent records being smashed. We review the data courtesy of Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler on Carbon Brief and The Climate Brink substack.

The contributors to 2023’s unexpectedly high warming include human forcing, a swift transition from La Niña to El Niño, a solar maximum, the Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption and a reduction in aerosol pollution from marine fuels. It turns out that even in combination, these do not provide a sufficient explanation for the warming that we experienced in 2023. What on earth is up with the climate? We are left with ‘natural variability’ and James Hansen’s explanation, but no satisfactory conclusion.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) released its Global Risk Report for 2024, showing that 63% of elite respondents to the WEF’s Perceptions Survey fear a global catastrophic risk event will occur in the next decade. The top four potential catastrophic risks they fear are environmental.

Why can’t we act? Are we zombies or just evolutionarily unfit? We say that there is just not enough research into the human cultural and social underpinnings of global catastrophic risks, and this requires urgent attention!

Are we there yet?

The year 2023 proved to be a defining year for climate change. It was a year in which temperature records, both on land and at sea, were not just broken, but absolutely pummelled. We experienced palpable climate phenomena, in vastly disparate places, bearing the unmistakable fingerprint of human-caused climate change. And we saw a range of different explanations emerge, some of which challenged the mainstream climate consensus. We also had the uncomfortable experience of witnessing the first UNFCCC climate conference run by fossil fuel interests, which had at least some success in making transparent the complete inadequacy of the current globally coordinated response.

One big question that emerged in 2023 was whether climate change was accelerating. Have we hit some kind of turning or tipping point?

For a comprehensive analysis of the climate record in 2023, you can’t do better than Zeke Hausfather’s State of the Climate report on Climate Brief, along with his and Andrew Dessler’s comments on the The Climate Brink substack. I’ve drawn some key information from these sources.

First of all, 2023 was unambiguously the warmest year on record:

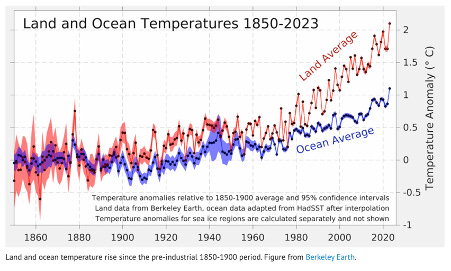

This result was unexpected. The actual surface temperature for 2023 was well beyond even the confidence intervals of the predictions for the year from the major datasets. Berkeley Earth recorded a 1.54˚C increase above pre-industrial levels for the year. It wasn’t just surface temperatures breaking records. It was also ocean temperature and Antarctic sea-ice extent. Splitting out the land and ocean surface temperatures, as can be seen in the chart below, reveals a particularly sharp spike in ocean heat content (OHC), as well as showing average surface temperatures over land surpassing 2˚C for the first time compared to pre-industrial levels.

According to Hausfather,

Last year was the warmest on record for the heat content of the world’s oceans. Ocean heat content (OHC) has increased by around 473 zettajoules – a billion trillion joules – since the 1940s. The heat increase in 2023 alone compared to 2021 – about 15 zettajoules – is around 25 times as much as the total energy produced by all human activities on Earth in 2021 (the latest year in which global primary energy statistics are available).

While the summer minimum for arctic sea-ice extent was the sixth lowest ever, the Antarctic hit new record lows for almost the entire year.

Antarctic sea ice was particularly low between June and November, shattering prior records by a substantial margin. While long-term trends in Antarctic sea ice have been ambiguous in the past (unlike in the Arctic where there is a consistent long-term decline), there is increasing evidence that human-driven warming is starting to drive significant loss of sea ice in the region.

The following chart shows Arctic (red line) and Antarctic (blue line) sea ice extent day-by-day for 2023, along with the historical ranges in corresponding shading.

Scientists have explored several possible reasons for the extreme results in 2023, including El Niño/La Niña, the Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption, the solar cycle, reductions in marine fuel pollution and anthropogenic forcing.

According to Hausfather

... both the Tonga eruption and the phase-out of sulphur in marine fuel are problematic explanations of extreme temperatures in 2023.

There is still a vigorous debate in the scientific literature about whether the eruption cooled or warmed the planet based on estimates of both sulphur dioxide and water vapour in the atmosphere, with some papers arguing for warming and others for cooling. Some modelling suggests that the largest impacts of the eruption would be in winter months, which does not match the timing of extreme summer temperatures experienced in 2023.

Similarly, the phase-out of sulphur in marine fuels occurred in 2020. If it had a large climate impact, it would show up in 2021 and 2022 rather than suddenly affecting the record in 2023. While it definitely has had a climate impact – alongside the broader reduction in aerosol emissions over the past three decades – the timing suggests that its likely not the primary driver of 2023 extremes.

Even El Niño – the usual suspect behind record warm years – does not clearly explain 2023 temperatures. Historically global temperatures have lagged around three months behind El Niño conditions in the tropical Pacific; for example, El Niño developed quite similarly in 1997, 2015 and 2023. But it was the following year – 1998 and 2016 – that saw record high temperatures.

This leaves us lacking a clear explanation for why global temperatures were so high in 2023. Andrew Dessler suggests here that the answer will probably turn out to be the result of natural variation. At the same time, Dessler argues, the models are predicting an acceleration in global warming in the future as greenhouse gases continue to grow, while aerosols decline, just not at the abrupt rate experienced in 2023.

This is not uncontroversial – in an opinion piece for the New York Times in October last year, Zeke Hausfather said

...while many experts have been cautious about acknowledging it, there is increasing evidence that global warming has accelerated over the past 15 years rather than continued at a gradual, steady pace. That acceleration means that the effects of climate change we are already seeing — extreme heat waves, wildfires, rainfall and sea level rise — will only grow more severe in the coming years.

I don’t make this claim lightly. Among my colleagues in climate science, there are sharp divisions on this question, and some aren’t convinced it’s happening.

He points to three lines of evidence:

the rate of surface temperature warming over the past 15 years has been 40% higher than the rate since the 1970’s;

there has been an acceleration in ocean heat content over recent decades (this is where 90% of global heating is stored; and

satellite measurements of earth’s energy imbalance show a big increase in the amount of heat trapped in earth’s atmosphere over the past couple of decades.

Adding an extra frisson of doubt is James Hansen’s paper, ‘Global Warming in the Pipeline’ which claims that climate scientists have underestimated climate sensitivity and that this has been masked in the models by a corresponding under-estimation of the cooling effect provided by aerosol pollution (which increases Earth’s albedo). He claims that the abrupt increase in global surface temperature experienced in 2023 is consistent with predictions in his paper. In a January 2024 communication, he and his co-authors said,

We expect record monthly temperatures to continue into mid-2024 due to the present large planetary energy imbalance, with the 12- month running-mean global temperature reaching +1.6-1.7°C relative to 1880-1920 and falling to only +1.4 ± 0.1°C during the following La Nina. Considering the large planetary energy imbalance, it will be clear that the world is passing through the 1.5°C ceiling, and is headed much higher, unless steps are taken to affect Earth’s energy imbalance.

This is considerably higher than the standard models are predicting (shown in the chart below). Another year of beating the model predictions in 2024 will certainly strengthen his case, but it still won’t prove definitive.

Davos jet-setters are worried

Meantime the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report for 2024 now has environmental risks occupying the top four spots over the next ten years, with AI propagated misinformation and disinformation in the near term lowering society’s ability to adequately address them.

The report worries about environmental risks hitting ‘a point of no return’, exploring the consequences of the world passing at least one ‘climate tipping point’ within the next decade.

Recent research suggests that the threshold for triggering long-term, potentially irreversible and self-perpetuating changes to select planetary systems is likely to be passed at or before 1.5°C of global warming, which is currently anticipated to be reached by the early 2030s. Many economies will remain largely unprepared for “non-linear” impacts: the potential triggering of a nexus of several related socio-environmental risks has the potential to speed up climate change, through the release of carbon emissions, and amplify related impacts, threatening climate-vulnerable populations. The collective ability of societies to adapt could be overwhelmed, considering the sheer scale of potential impacts and infrastructure investment requirements, leaving some communities and countries unable to absorb both the acute and chronic effects of rapid climate change (P. 7).

One of the recent research studies that they refer to is The Global Tipping Points Report, found here. The WEF’s perceptions survey reveals a remarkably pessimistic outlook with 63% of correspondents believing that the risk of a global catastrophe occurring within the next ten years is either highly elevated or looming.

The sense that things are not going well and that we are heading into very turbulent and stormy times turns out to be widespread, at least among ‘the Forum’s extensive network of academic, business, government, civil society and thought leaders’ (p. 99) who were canvassed for the survey. If you are worried, you are very definitely not alone – the global elite is right there with you, also very worried.

For my money, the most striking aspect of all of this is the extent to which ‘business as usual’ is the dominant approach for private business, governments and, of course, COP28. “Cross-border cooperation”, WEF claims “remains the only viable pathway for the most critical risks to human security and prosperity” (p. 92). If COP28 is anything to go by, trouble is indeed looming.

How can the entire global elite be so very, very worried and so very, very unresponsive, all at the same time? Has the Zombie Apocalypse already happened? I’m a big fan of zombie movies and now I’m worried that I blinked and missed the real-life event...

‘Our lizard brains make us (not) do it’

One possible explanation for why we just can’t seem to act is that we are evolutionarily ill-equipped for it. Phys.org welcomed the New Year with this cheery little piece entitled Evolution might stop humans from solving climate change. It’s based on a paper out of University of Maine by Timothy M. Waring et al.

Tackling the climate crisis effectively will probably require new worldwide regulatory, economic and social systems—ones that generate greater cooperation and authority than existing systems like the Paris Agreement. To establish and operate those systems, humans need a functional social system for the planet, which we don't have...The other problem is much worse, Waring says. In a world filled with sub-global groups, cultural evolution among these groups will tend to solve the wrong problems, benefiting the interests of nations and corporations and delaying action on shared priorities. Cultural evolution among groups would tend to exacerbate resource competition and could lead to direct conflict between groups and even global human dieback.

They suggest that more research is required that might lead to novel policy solutions.

This is probably quite important. It is very strange, but true, that at no point in the history of the climate change crisis has the world ever lacked the technological know-how to address it. Yet we spend almost all of our research investment on additional technological solutions tackling various symptoms of the problem. Technologies that we consistently fail to adopt at the scale required or that fail to address the core drivers of the problem. If humanity fails to address climate change, it won’t be because we didn’t know how or lacked the means. It will be because behavioural and cultural traits, along with their systemic arrangements, got in the way.

We should be pouring money into researching the underlying social and human drivers of catastrophic risks, and how to shift them. Yet we consistently favour STEM research over social science. To the extent that the technology is now hastening us toward the edge (specifically, the AI propagated misinformation and disinformation highlighted in the WEF report).

An over-shooting crisis of human behaviour

On that note, a New Zealand-led research paper that examined the underlying behavioural drivers of ecological overshoot is starting to be picked up by international media. The team’s paper, led by conservationist Joseph Merz, featured in a column written by podcaster Rachel Donald (Planet Critical) in the Guardian this month.

“Essentially, overshoot is a crisis of human behaviour,” says Merz. “For decades we’ve been telling people to change their behaviour without saying: ‘Change your behaviour.’ We’ve been saying ‘be more green’ or ‘fly less’, but meanwhile all of the things that drive behaviour have been pushing the other way. All of these subtle cues and not so subtle cues have literally been pushing the opposite direction – and we’ve been wondering why nothing’s changing.”

And finally, circling back to the mis- and disinformation issue, this report on new forms of climate denial from the Centre for Countering Digital Hate was published this month. The researchers use an AI model to measure the rate of growth over the last five years of what they term “new climate denial” on Youtube. ‘New denial’ is defined as “the departure from rejection of anthropogenic climate change, to attacks on climate science and scientists, and rhetoric seeking to undermine confidence in solutions to climate change. “New Denial” claims now constitute 70% of all climate denial claims made on YouTube, up from 35% six years ago.”

I’m interested to hear your thoughts and comments on this report. I think they are on to something important, but have some reservations about grey areas, loose definitions, the ability of AI to distinguish between denial and legitimate debate, and the potential uses of the ‘new denial’ framing.

Share this post