TL;DR: Here’s the top six news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa-NZ this week, and a discussion above that was recorded this afternoon between Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer:

A recent surge in oil and gas development activity is threatening to overwhelm climate goals, with plans already approved that would quadruple new developments by the end of the decade, according to a new report by Global Energy Monitor.

If fossil fuel demand peaks in the next couple of years, as currently predicted by the IEA, the stranded assets related to this investment surge could create a financial crisis. Failure to peak, on the other hand, will provoke a climate transition crisis.

The US, already leading the surge in new oil and gas developments over the last two years, is likely to see a regression in green policies, should Donald Trump win the election later this year, putting further pressure on global goals, according to a former UN climate chief.

Meanwhile, a new study has linked climate change to food price inflation, finding that ‘heatflation’ could cause food prices to rise as much as 3 percentage points per year in just over a decade. The effects are likely to be most inflationary in regions and seasons that are already hotter, meaning that much of the Global South, where food costs make up a much higher proportion of overall living costs, will suffer the most.

As measurement improves, fossil methane leaks are proving to be considerably higher than previously understood, according to Clean Technica. Methane leaks from US landfills are also proving to be at least 40% higher than reporting to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) would suggest.

Salt, air and bricks may be about to replace lithium, cadmium and nickel, as industrial energy storage options emerge that use simpler technologies and ingredients compared to conventional batteries.

Bernard and Cathrine will be talking about these topics in a shorter way on today’s Hoon from 5.10 pm to 5.20 pm.

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

A predicted surge in fossil fuel production

As lengthy debates about the language of fossil fuel emissions reductions took place at COP28 last year, approvals for new oil and gas field developments were returning to pre-Covid levels.

In a new report this week from Global Energy Monitor, it seems the industry now plans to almost quadruple the number of new developments (and the amount of oil and gas extracted) compared with 2023, by the end of the decade.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) warned in 2021 that an end to new oil and gas field development was required to achieve their 1.5˚C Net Zero roadmap. More than 20 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe) have been announced since then.

Scott Zimmerman, Project Manager for the Global Oil and Gas Extraction Tracker at Global Energy Monitor said,

“Oil and gas producers have given all kinds of reasons for continuing to discover and develop new fields, but none of these hold water. The science is clear: No new oil and gas fields, or the planet gets pushed past what it can handle.”

According to the Stockholm Environment institute (SEI), fossil fuel producers are planning to push production of oil and gas 29% and 82% higher, respectively, than what is consistent with a 1.5˚C target.

The language of ‘net’ and ‘unabated’ emissions, key sources of debate at COP28, seem designed to obscure the unrelenting trajectory of oil and gas extraction. While it is true that clean energy as a proportion of electricity generation has doubled since 2007, new oil and gas extraction has more than kept up. And while coal production looked for a while to have peaked in 2014, it has since rebounded to an all-time high of 8,741 Mt in 2023, 1.8% over 2022.

The US is now the world’s largest oil and gas producer, leading the surge in projects over the past two years. However, that situation could worsen in the event of a victory for Donald Trump in the US election later this year. A likely regression in green policies would have global impacts, according to former UN climate chief, Patricia Espinosa, putting further pressure on current climate goals.

So was Saudi Aramco CEO Amin Nasser just being brutally honest two weeks ago, when he said the current energy transition strategy was “visibly failing on all fronts”?

For a transition to actually take place, it requires not just more clean energy, but less fossil fuel production, and the latter has yet to occur. Nasser went on to suggest, to general applause at the conference he was attending, that policymakers should “abandon the fantasy” of phasing out oil and gas . I don’t think he intended that they should replace the fantasy phaseout with one based in reality.

The IEA’s latest claim, that 2024 or near-abouts, will prove to be the peak year in global demand for fossil fuels, presages one of two crises – either fossil fuel demand will continue to grow, proving the IEA wrong and the energy transition itself in crisis, or it will actually peak, proving the industry out-of-step with reality and provoking a financial crisis in relation to stranded assets. The latter may be the best-case scenario, but still represents a vast misallocation of resources and a painful adjustment period (where ‘pain’ likely corresponds with ‘conflict’). OPEC, of course, claims that it would unleash “energy chaos” and “dire consequences for economies and billions of people across the world”.

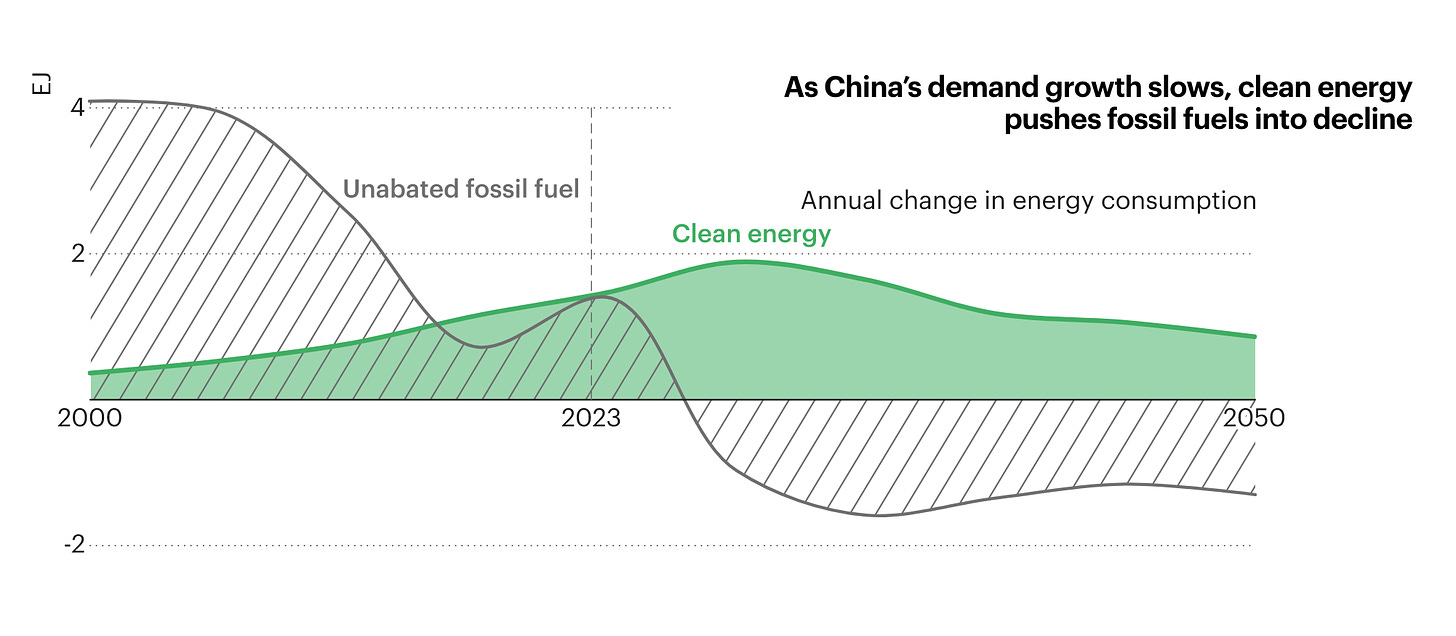

The IEA predicts fossil fuel declines will follow hard on the heels of the current rebound:

Source: IEA (2023) World Energy Outlook 2023: Overview and Key Findings.

It is clear that 1.5˚C will be surpassed, but the big question that remains is, when will the energy transition really begin and what global temperature increase will already be baked in by the time it starts?

Meanwhile, a new study has linked climate change to food price inflation, finding that ‘heatflation’ could result in food prices rising as much as 3 percentage points per year in just over a decade! According to lead author Max Kotz, a climate scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:

“The physical impacts of climate change are going to have a persistent effect on inflation. This is really from my perspective another example of one of the ways in which climate change can undermine human welfare, economic welfare.”

The study looked at more than 20,000 data points to identify the causal link between extreme weather, particularly heat, and rising prices, before projecting future impacts from climate change.

They found that the effects are likely to be exacerbated in places and seasons that are already hotter, meaning much of the Global South would suffer worse food price inflation than the rest of the world, against a context in which food makes up a much larger proportion of peoples’ daily budget.

Methane leaks and blowouts

It turns out that natural gas isn’t burning as cleanly as previously thought, according to an article in Clean Technica. New information from scientific studies, measurement campaigns and satellite data is revealing big gaps in self-reported information, with the highest sources of leaks often not where companies expected. The IEA’s Global Methane Tracker 2024 reports methane emissions from the energy sector remain near record highs and large methane emission events, detected by satellites, rose by more than 50% in 2023 compared with 2022. That includes one major blowout in Kazahkstan that continued for more than 200 days.

In one example reported in Scientific American, it was found that US landfills have been leaking methane at levels that are at least 40% higher than what was being reported to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Most operators report on the basis of an estimate, following EPA guidelines, that is calculated from the amount of rubbish taken in. However, recent information from Carbon Mapping, that is based on infrared images taken from airplanes, as well as new data from drones and satellites, reveal super-emitting hotspots that can persist for years are responsible for as much as 90% of measured emissions.

Simpler energy storage?

In brighter news, Roger Harrabin reports in the Guardian on the future of energy storage, in the form of salt, air and bricks. While the focus of industrial storage to date has been on giant conventional chemical batteries, using ingredients like lithium, cadmium and nickel, there is growing interest in using heat to store energy using simpler systems and more readily available ingredients like air, salt and bricks.

One example is tanks of molten salt, charged by electricity during periods of energy abundance, which can then hold heat at temperatures up to 500˚C. In addition, salt tanks can be recharged thousands of times for up to 40 years, at least three times longer than current industrial storage options.

Likewise, bricks can be heated to 1,500˚C and lose less than 1% of the heat per day. Other start-ups are investigating heat storage in steel and concrete. Compressed and super-cooled liquid air are also being developed as potential energy storage devices.

However, some of these approaches will need backing if they are to avoid being left at the side of the road in the rush to reduce emissions. It’s possible that support will accumulate more easily for established technologies, even if they are not the most fit for purpose.

Share this post