TLDR: Aotearoa’s Government effectively decided without debate in late 2021 when it created the $4.5 billion Climate Emergency Response Fund that it would be fiscally neutral, which means it does not increase the Government’s debt and does not ‘pay forward’ investment by today’s taxpayers to help future taxpayers deal with or reduce the pain of climate change.

The fund essentially recycles revenues from the Emissions Trading Scheme (typically from higher petrol and diesel costs) into operational and capital spending on climate measures. The other flagship climate policy introduced by the Government, the Clean Car Rebate, does the same. Revenues from levies on high emissions vehicles are meant to be recycled into rebates or discounts on low emissions or no emissions vehicles so there’s no deficit that taxpayers at large would have to pay for.

But these fiscally neutral policies actually extend an intergenerational wealth crime of at least the last two decades, whereby today’s taxpayers and the politicians wanting their votes skimp on investment and policies to reduce climate emissions, knowing that the costs will land on the unborn and those too young to vote now. A fairer way to respond to climate change now would be use the most conventional tool for spreading costs (and benefits) more fairly over multiple generations: to consume today’s assets or borrow to invest in other assets or spending. The slightly higher interest costs for taxpayers effectively avoid lumping all the costs on today’s taxpayers and smear them out over the long run.

The Government’s decisions so far to only have fiscally neutral climate policies and to prioritise debt reduction have shown where its real priorities, and those of the median voters lie: low debt and low mortgage rates to keep asset values high.

Is this the rainy day we’re saving for? Or is it this century?

The phrase ‘we need to save for a rainy day’ is intuitively easy to understand for anyone listening to a Labour or National politician or Treasury official arguing for Government spending and investment restraint because the ‘rainy day fund’ will be needed for some vaguely realistic, but far-enough-off-in-the-future risk to justify not spending now.

The implication is that rainy days are unusual and that the nation is better off saving for an unspecified but large risk, than spending or investing now on either consuming now or building other more ‘normal’ infrastructure. That’s how the Government has operated for the last 30 years: spending rightly and heavily in emergencies such as the GFC, Christchurch earthquakes and covid pandemics, but defaulting back to ‘prepare for future rainy days’ mode when the crisis has passed by prioritising deficit reduction, strangling investment spending and reducing the Government’s net debt to GDP.

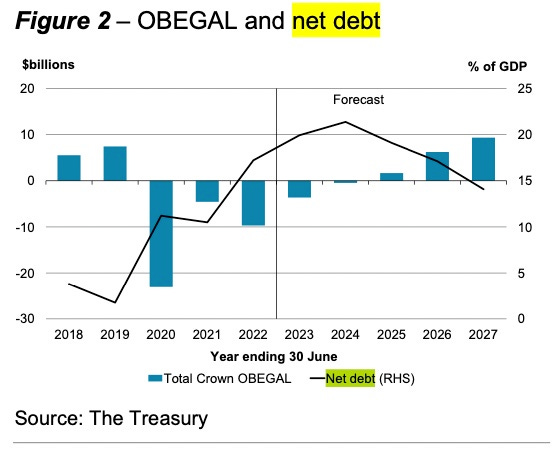

That’s why this chart below is the second chart in Treasury’s last fiscal and economic update in December. It is our political economy’s north star. In the minds of Treasury officials, finance ministers and therefore Cabinets, any decision involving spending, taxation, borrowing or investment is always eventually focused on getting that net debt line bending down out in to the future, and preferably well below the ‘ceiling’ specified by Treasury. For most of the last 20 years the ceiling was gross debt of 20% of GDP. Then-Finance Minister Steven Joyce tried to lower that to 10-15% of GDP in 2017. It was tweaked to net debt of 30% of GDP last year, which is also

The Government’s guiding force (for both National and Labour) for 30 years has been focusing on getting net debt down again as soon as a crisis has passed. It’s why then Finance Minister Bill English crunched down infrastructure spending from 2012 to 2017 because he (and Treasury) believed the nation’s finances needed to have more ‘headroom’ to deal with the next shock once the quakes were over. It’s why now-Finance Minister Grant Robertson has argued he needs to take a ‘balanced approach’ to increasing spending on social services and infrastructure, releative to debt-to-GDP reduction. Now the covid crisis is over, the focus is on debt reduction ahead of the next ‘rainy day’.

But what if the rainy day is today and actually just a series of days off into the indefinite future. Does ‘saving for a rainy day’ make sense when the rainy day is now, always and forever?

Short term pain always trumps long term gain and pain

Humans are not very good at assessing the benefits and costs of decisions that have effects and costs over a very long time period. We tend to hate losing things now much, much more than the same gain some time off in the future. Studies show the pain of losing something now is twice as large in perceived terms as the actual same amount of gain in the future. It’s called ‘loss aversion’ and it’s a key problem in the political economy.

We saw that writ large today when we had the apparently perverse combination of a Government choosing to increase subsidies for burning petrol and diesel to generate more climate emissions on the very same day our biggest city experienced its third extreme weather event in four days, which is clearly caused by climate change.

The cognitive dissonance fair clanged out across the political economy.

The short term matters more than the long term for Hipkins

Lynn and I went to the news conference this afternoon where Chris Hipkins joined Transport and Auckland Minister Michael Wood and Finance and former Infrastructure Minister Grant Robertson to announce the extension of the fuel tax cuts.

They made the announcement in central Auckland after visiting a relief centre in Mangere catering for people flooded out of their homes by the most expensive climate change disaster in our history. Hipkins was repeatedly challenged at a news conference to justify the extension of subsidies to create more climate emissions by burning petrol and diesel when the effects of climate change had just proved so disastrous.

“The Government has an extensive climate change programme underway. We’re absolutely focused on reducing emissions. The public transport (fare) reductions, for example, that we’ve put in place today, are a positive step in terms of getting more people into public transport.

“And we’ve got extensive work going on around the electrification of the vehicle fleet. We’ve got a lot of work happening to reduce our emissions overall as a country in the electricity generation space,” he said.

“But we also have to acknowledge that right here and right now, that increase in fuel costs is putting a significant amount of pressure on families who have no choice but to continue to fill up the car.” Chris Hipkins.

Hipkins repeatedly went back to his initial comments as PM that he wanted to focus the Government on ‘bread and butter’ issues.

Challenged directly if he was prioritising ‘bread and butter’ issues over climate change action, he said:

“No, absolutely not. The work on climate change continues. We still have an extensive Emissions Reduction Program. In reality, the cost of a tank of gas going up by 25 cents a litre, if that was to happen straightaway, wouldn't reduce the amount of fuel being consumed by households.

“They still have to find that money from somewhere at a time when they often can't find that extra funding. So this is easing some of the financial pressure, but our work to come to reduce emissions will continue.” Hipkins.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

Share this post