Long stories short, here’s the top six news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa this week, and a discussion above between Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer:

Are our institutions capable of bending, not breaking, in the face of accelerating climate risk? Climate risk is systemically underestimated in the climate scenarios that are used by central banks, including the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, to test the stability of the financial system. The latest update to scenarios from the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) forecast much higher economic losses from climate change, but is it enough?

Net-Zero requires a ‘like-for-like framework’ in which only permanent storage can reverse the climate impact of fossil carbon emissions, says Zeke Hausfather. The realisation that planting trees cannot compensate for fossil fuel emissions is beginning to dawn.

The Helen Clark Foundation released a report warning that 10,000 houses are set to become uninsurable in Aotearoa as climate risk grows, suggesting that the country “is just one major disaster away from insurance retreat becoming a much more complex problem that it already is”.

Australia has given the go ahead to another mammoth fossil fuel emitting gas project. Western Australia’s Labour Government has announced plans to ditch state emissions reduction requirements in order to clear the path.

UN Chief António Guterres opens COP29 with another headline grabbing quote, opining that “[t]his year has been a masterclass in human destruction.”

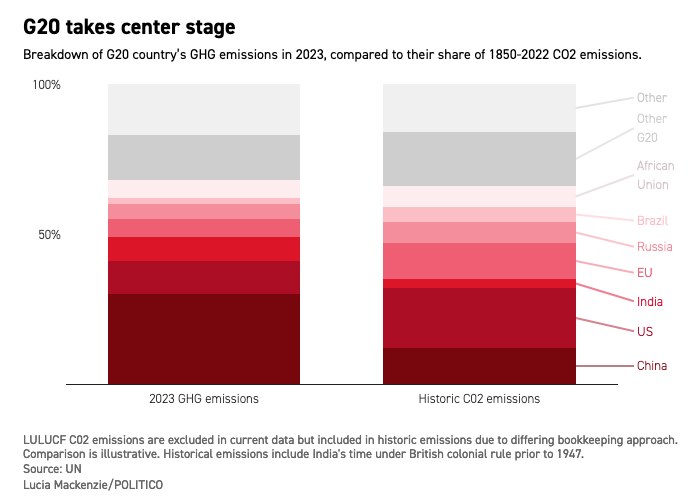

The Chart of the Week focuses on the source of debates about responsibility at COPs - current versus historic emissions of key countries.

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the video and podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

1. Underestimating the risk of financial collapse

One of the most important equations in economic modelling of climate change is the damage function. The damage function determines the economic losses associated with additional warming.

This week, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) released updated climate scenarios, with a new, much higher damage function.

If you have heard the terms ‘orderly’, ‘disorderly’, ‘too little too late’ or ‘hot house world’ used to describe possible transitions, then they are likely referring to scenarios developed by the NGFS.

The NGFS is a network of central banks that was established following the Paris Agreement with the aim of improving the global management of climate risk and to try to mobilise finance to support the transition to a sustainable economy. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand is part of the network, and uses climate scenarios developed by the NGFS to test the stability of the financial and banking system in Aotearoa.

The damage functions used in economic modelling in general, and the NGFS climate scenarios in particular, have been criticised for systemically underestimating risk. The importance of this is difficult to over-emphasise. The global financial system is tightly interconnected and proved to be frighteningly fragile during the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007-2008. A lot of work has gone in to trying to build more stability and resilience into the system since then. Part of that effort involves the regular testing of stability in the face of climate damage using the NGFS climate scenarios.

Governments have proven reluctant to act on the increasingly strong advice of climate scientists, relying heavily instead on economist’s projections of the impact of climate change on the economy. If those projections underestimate economic damages, then they are unlikely to enact policy that is proportionate to the true scale of the risk. There are other factors that lead governments to underreact to climate change, but the prospect of limited economic losses provides a highly significant contribution. Any update to the most commonly used damage functions is meaningful. Despite underpinning the global response to climate change, its influence is largely invisible to most people. This single mathematical function lies at the heart of a profound disconnect between climate scientists and economists.

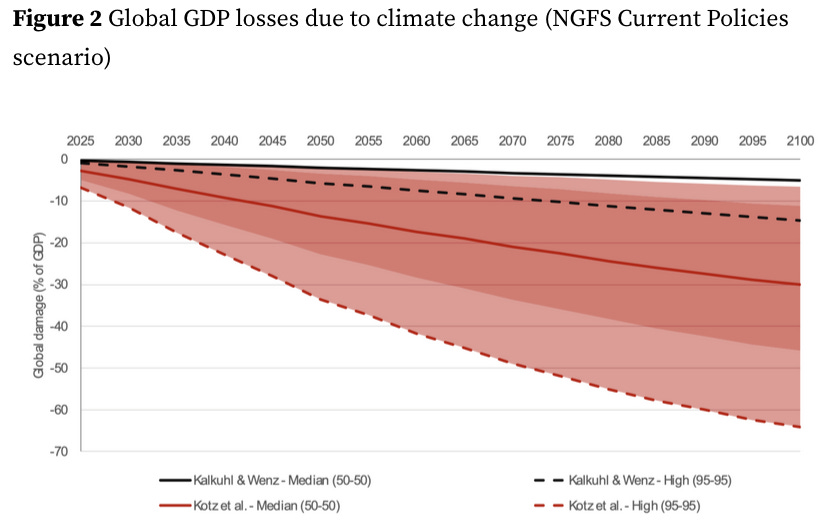

The analysis performed by the NGFS considered a range of estimates from the literature, landing on one of the higher estimates from Kotz (2024), who forecast mean economic losses of 33% of GDP by 2100, in the absence of further climate action (19% losses for each 1˚C of incremental global temperature increase), the red line in the chart below.

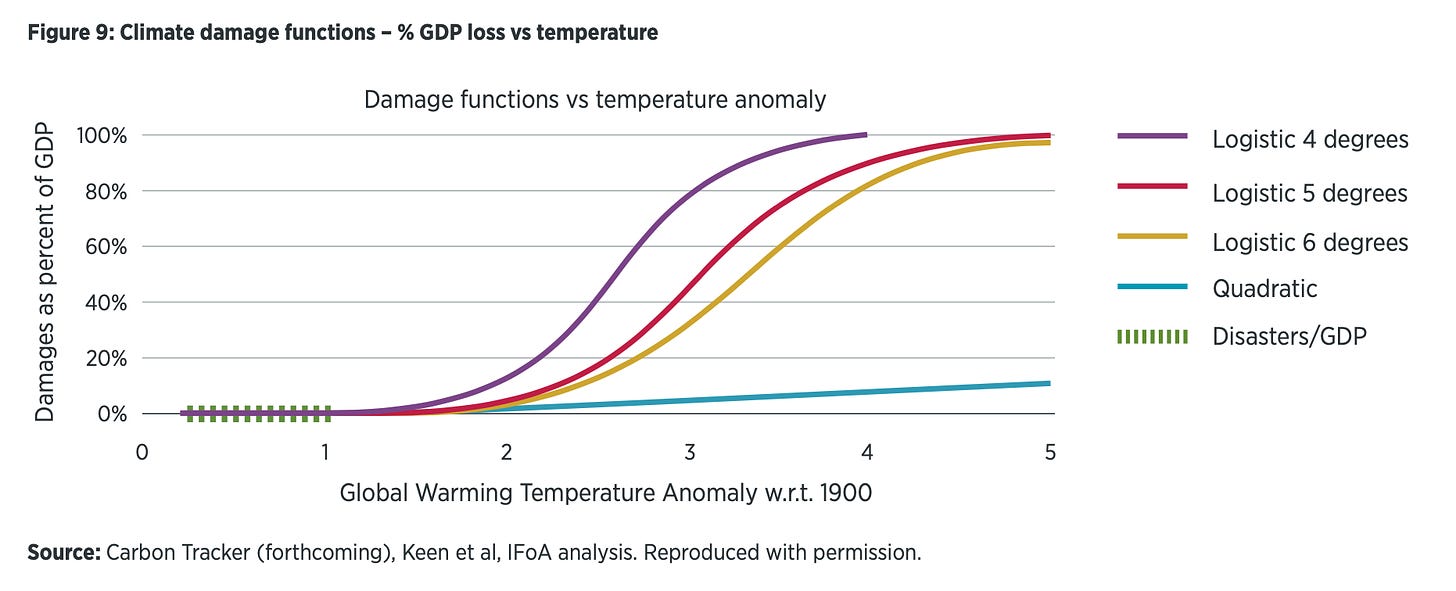

A report last year from the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) and the University of Exeter was critical of the way that damage functions are calculated. They were concerned that climate tipping points, amongst other anticipated extreme climate impacts were not being included in projections..

One of the authors of that study, Sandy Trusk, was quoted in the Guardian, responding to the new NGFS scenarios.

“This is a massive one-third hit from physical damage on GDP. It has increased more than five times, from about 6% to 33%.

“But while this is a much more severe damage risk, it is by no means comprehensive. The analogy I would use is a model of the Titanic where you can see the iceberg, but the modelling fails to recognise that there are not enough lifeboats on board, or that the cold water is a threat to human life. So this report is still systemically underestimating the risk.” The Guardian

Rather than making incremental improvements to projected economic damages based on historic experience, the IFoA report recommended listening to climate scientists when they say that a stable modern civilisation is incompatible with temperatures above 4˚C. They recommend using a log damage function that assumes 100% GDP loss at a certain level of warming, say 6˚C, 5˚C or 4˚C, saying that even 3˚C may be extremely challenging to adapt to. Those damage functions would look like the chart below. If you were to tip the blue quadratic line upwards so that it passed through 33% damages at 3˚C, you would have a representation of the latest NGFS damage function compared to where they sat before.

The NGFS report acknowledges that the future economic outlook may be significantly worse than their damage function suggests,

“It cannot be excluded that the economic effects of climate change might turn out to be even more severe than visualised under the NGFS scenarios, for instance, if certain tipping points are reached,” the report said.

“Thus, users should also take into account the tail risks of climate change, along with other risks such as nature-related ones, which are not necessarily captured by these scenarios.” The Guardian

The problem is that most of the decision-makers using information gleaned from climate scenario analyses are unlikely to be paying attention to the uncounted risks, simply because they are uncounted. After all, the damage function is meant to represent the risk of damage, and policymakers respond to numbers, not caveats.

The systemic underestimation of economic risk is directly related to systemic policy under-reactions by governments, increasing the chances of those unaccounted-for tail risks actually occurring. One argument for continuing to underestimate the economic damages of climate change is the possibility that an accurate understanding of the risks by investors would simply bring forward the date of a financial collapse. The ability of our financial and democratic institutions to bend, not break, in the face of true climate risk so far remains untested.

2. Planting trees can’t remove fossil carbon emissions from atmosphere

The realisation is beginning to dawn that temporary carbon sinks, from planting forests for instance, cannot off-set ongoing fossil fuel emissions.

At best, says climate scientist Zeke Hausfather, they can help to minimise peak temperatures and counterbalance land use emissions. Net-Zero requires a ‘like-for-life framework’ in which only permanent storage can reverse the climate impact of fossil carbon emissions, according to his recently co-authored publication in Nature.

“Here we see that only permanent storage fully reverses the climate impact of a pulse of CO2 emissions over a 500-year timeframe. Notably, there is no significant cooling of the climate that occurs after the emissions pulse, suggesting that we cannot use temporary climate removal to buy time until the climate cools back down (similar to how geoengineering would not actually solve the problem).

This reinforces the finding (by many of the climate scientists behind the idea of net-zero emissions) in Allen et al 2022 that “durable, climate-neutral net zero strategies require like-for-like balancing of anthropogenic greenhouse gas sources and sinks in terms of both origin (biogenic versus geological) and gas lifetime” and that “the requirement that any continued generation of fossil CO2, whether or not it is emitted to the atmosphere, must be balanced by geological CO2 sequestration or equally permanent disposal.” The Climate Brink

This aligns with a 2022 suggestion from New Zealand’s Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Simon Upton, that forestry sinks should only be applied to off-setting biogenic agricultural emissions, although his calculations suggest that only a fraction of the warming from agriculture could be offset that way in Aotearoa, even with extensive planting.

The fly in the ointment is another dawning realisation – that permanent geological storage solutions (carbon capture and storage) are not delivering on expectations and may never scale quickly enough to be of much use.

3. New insurance retreat study suggests the Government act now

Another study, this time from the Helen Clark Foundation warns that 10,000 properties could become uninsurable as climate risk grows. This reinforces finding from insurance retreat modelling published in an article earlier this year (Storey et al., 2024).

“The report is also urging policymakers to cease "inappropriate" development in flood zones, flood-prone areas, and coastal locales that are set to become uninsurable in the coming decades.

Government intervention is also being called for, including the development of a residential flood insurance scheme, similar to arrangements seen in the UK and France.

"Such a scheme, depending on its design, could aim to fill any of several different potential future 'protection gaps'," the report said.

This could include homes that are unable to access private insurance but were still within a risk threshold, homes in areas where insurance has been withdrawn because of risk, and homes that are facing a future process of planned relocation, and require cover in the interim.”

The country, they say “is just one major disaster away from insurance retreat becoming a much more complex problem that it already is”.

4. Australia approves another mammoth emissions-emitting project

Western Australia’s state government has announced it plans to abolish state-emissions reduction requirements, clearing the path for one of the country’s largest emitters, a Woodside gas production plant, to continue operating for another fifty years.

“Scientists have warned the proposal to extend the life of the North West Shelf gas processing plant on the Burrup Peninsula in the country’s remote north-west is linked to the development of at least three major gas fields and could ultimately result in billions of tonnes of climate pollution being released into the atmosphere.

The WA Environment Protection Authority recommended in 2022 that the state approve a 50-year extension for the plant, which is run by the oil and gas company Woodside, as long as it progressively reduced its operating emissions. It could do that by making cuts onsite or paying for carbon offsets.

More than 750 organisations and individuals lodged appeals against the recommendation – a record for the state – citing its contribution to the climate crisis and potential damage to Indigenous rock art. The WA appeals convenor has been considering the objections since mid 2022.

But the WA government last month announced it would change rules so that the EPA would no longer regulate emissions from development proposals that released significant climate pollution.” The Guardian

The decision highlights the inadequacy of Australia’s ‘safeguard mechanism’ that requires the country’s 215 largest industrial emitters to cut their emissions intensity by 4.9% a year until 2030.

5. A masterclass in human destruction

COP29 has kicked off, with another great quote from UN chief António Guterres to mark the moment. “This year has been a masterclass in human destruction”, he told attendees at the summit.

“Families running for their lives before the next hurricane strikes; workers and pilgrims collapsing in insufferable heat; floods tearing through communities and tearing down infrastructure; children going to bed hungry as droughts ravage crops,” he said. “All these disasters, and more, are being supercharged by human-made climate change.” The Guardian

In response, the UK has confirmed its commitment to an 81% reduction in emissions by 2035 compared with 1990 levels, with new policies likely to be needed to encourage a switch to public and active transport, and from gas heating to electric pumps.

UK leadership will not make up for the abyss created by Trump’s election in the US. Also likely to be missing from the summit is strong leadership from the EU who are about to miss the deadline for NDC commitments amidst internal dissent about the European Commission’s recommendation for a 90% emissions reduction target for 2040, with the 2035 target to be derived by drawing a straight line between that and the current 2030 target.

“Some countries feel that the bloc is doing enough and it’s time for other countries to step up, as the EU now accounts for only 6 percent of global emissions. (The bloc is responsible for 12 percent of carbon dioxide released since the pre-industrial era.)

“We don’t give ourselves enough credit,” said the Polish official, who was granted anonymity to speak freely. “We are leading by example, and it’s an excellent example.”

“The EU has already done a lot for climate,” a senior climate negotiator from another EU country said. “My government even thinks Europe is doing too much.” Politico

Meantime, the President of COP29’s host country, Azerbaijan, has described oil and gas as a “gift from God”, as the country’s negotiators were filmed seizing opportunities during conference discussions to secure gas deals. The country plans to expand gas production by up to a third this decade.

6. Chart of the week: The G20 under the spotlight at COP29

Arguments over who is responsible for climate warming, and who should contribute most to climate financing, particularly for loss and damage in developing countries, often focus on historic versus current emissions.

Source: Politico

Ka kite ano

Bernard and Cathrine

Share this post