TLDR & TLDL: The Government has announced a swathe of housing policies aimed at increasing housing supply for rentals and owner occupiers, all with the loudly-stated aim of improving affordability. That included a broad housing policy statement aimed at councils and others that didn’t say what amount of affordability improvement it wanted, and to what level.

It also confirmed the specifics of its March 23 tax deductibility ‘shock’, which ended up not slowing the market, and may have the unintended consequence of pushing up the price of new-builds and risks for banks. It may even force the Reserve Bank to further restrict new lending for new builds to avoid a buildup in banking system and macroeconomic risks.

It’s a bit like calling up Google Maps and typing in ‘somewhere over there’ at ‘some point in the future,’ and hoping the app works it out while your passengers enjoy the drivers’ commentary and scenery. The vagueness allows the Government to signal its virtues in favour of affordability without having to take the real actions it knows median voters won’t allow: unleashing a supply and wealth tax shock with the specific aim of lowering house prices and resetting inflation expectations.

(I’ve opened this one up to both free and paid subscribers given the public interest in housing affordability. I’d welcome the support of anyone who hasn’t subscribed yet to take up the 50% off deal for an annual subscription to support my housing affordability journalism.)

Click here to subscribe for one year for a one-off payment of $95. That’s a 50% discount on the usual annual price and 58% off the monthly price. The offer will be open for a week ending October 6. It’s open to anyone who clicks on it. Please pass on the link to friends, family and colleagues, so they can subscribe too. Just copy and paste this link. and send on to your colleagues, or share on social media. https://thekaka.substack.com/housingaffordabiltyoffer50percentoffforoneyear

Thanks for you support and I welcome your comments and help in reporting on this issue, which I think is Aotearoa-NZ’s biggest challenge in the long run, along with the closely-connected issue of climate change. Support my work by subscribing here with this deal.)

At the moment, the current Government’s strategy of using the housing market as a wealth creation tool to support the economy (and its opinion poll support) during Covid, and refusing to use its lightly-geared balance sheet to signal a long-term housing supply dump, has been responsible for a 46% rise in house prices and a 12% increase in rents over the last four years. During that time average wage and salary rates rose 7.8%.

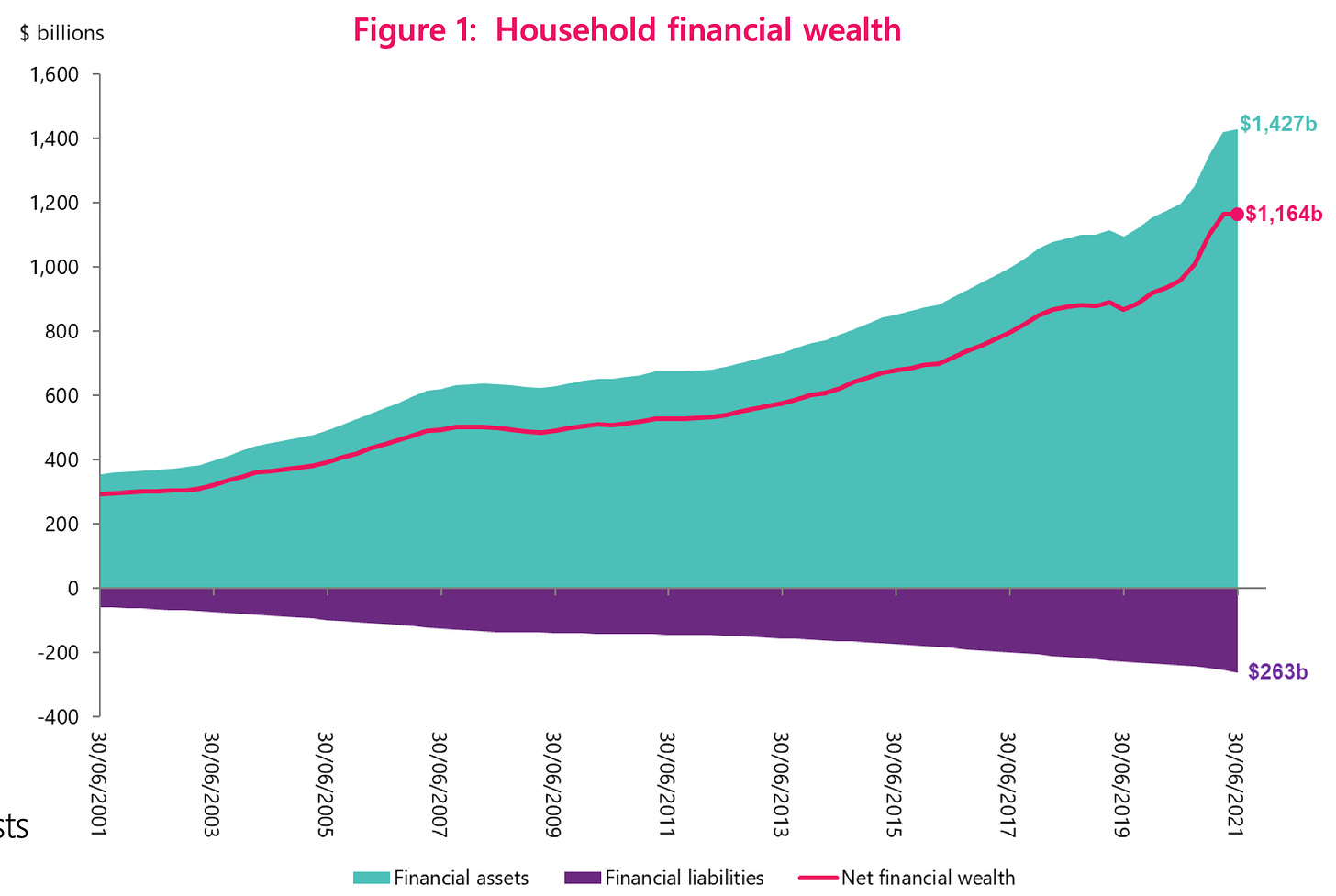

The Government’s strategies since it was sworn in in October 26, 2017 have delivered a housing market that grew house prices 5.9 times faster than wages and 1.5 times faster than wage growth. Over that time, the owners of homes, both owner occupied and rentals, saw the net equity in their homes rise $423b to $1.24b, but the prospect of home ownership or affordable rental property (to help build up a deposit) has receded so far into the distance many have given up.

The Government has launched a state house building programme, but has also repeatedly reassured home owners and investors that it won’t tax their capital gains ‘in Jacinda Ardern’s political lifetime’ and wants ‘sustained moderation’ in house price inflation, rather than any outright falls in prices.

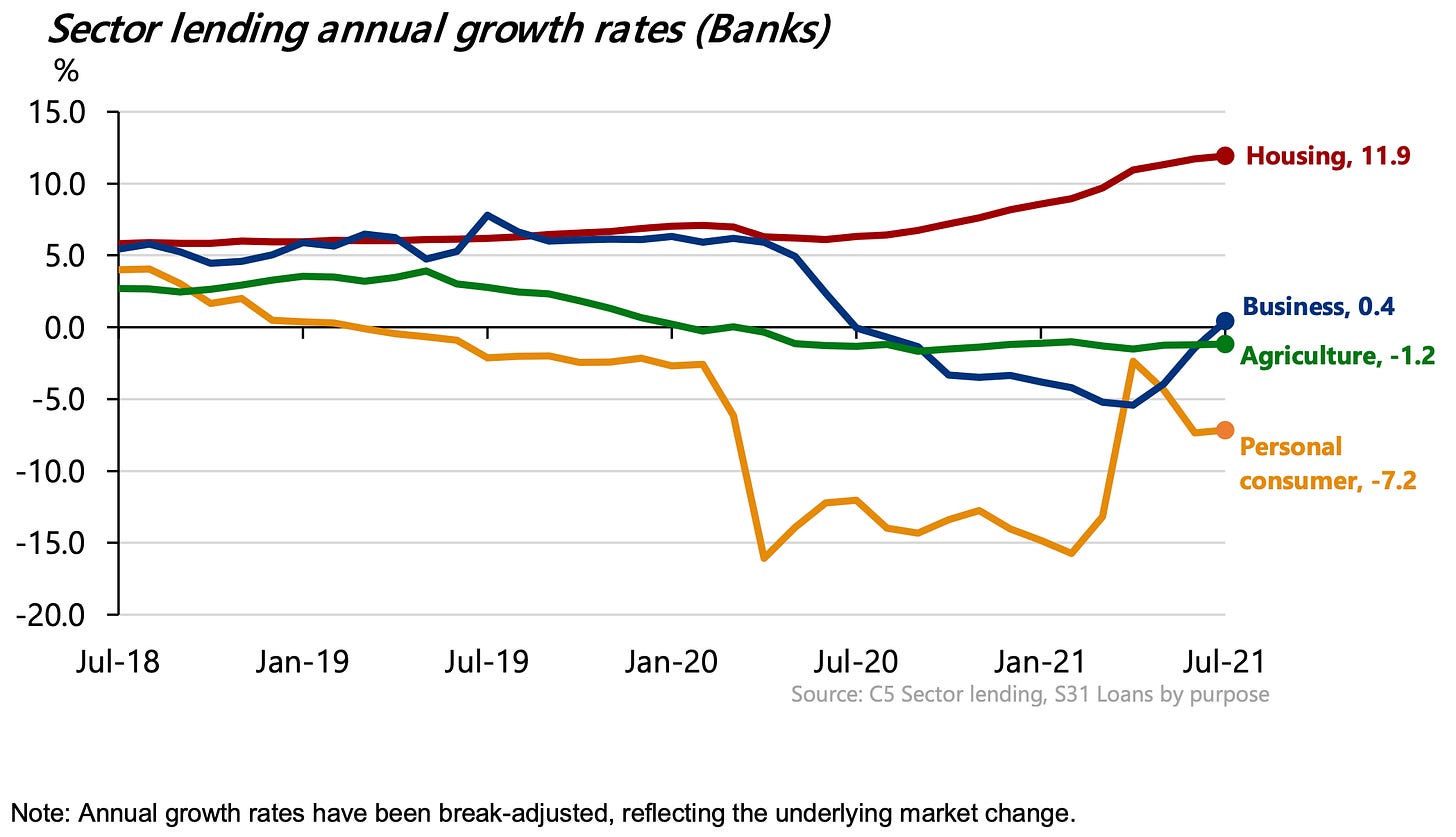

The Reserve Bank also acted quickly last year to ensure house prices didn’t fall because of the shock of Covid by printing over $60b to lower mortgage rates and relaxing lending restrictions, albeit for a year in which banks pumped an extra $35b of lending into the market, increasing mortgage debt by 12.8% in 12 months.

Property owners know neither Labour and its Green partners nor the National Party will act in a way that lowers house prices back to current levels, let alone the ones in place in late-2017, when the Prime Minister described the housing market as in crisis.

Effectively, the market has a de facto government-guaranteed floor that keeps ratcheting up at a rate that is doubling prices every seven or eight years. I’ve outlined in this previous piece what ‘pulling all the levers’ to achieve affordability would mean. The Government is doing none of them at the pace or scale (or at all) needed to stop prices from ratcheting up.

PM Jacinda Ardern reassured owners last December when the government signalled some action to cool the market that it wanted “sustained moderation” in house price inflation, which she described as something like the 4-5% the Labour/NZ First/Green Government had seen in its first term. Given household disposable income growth of around that level each year, that would imply no improvement in affordability for buyers. Rental inflation has also exceeded income growth since then.

So what just happened?

Yesterday the Government took a couple of actions to publicly advertise its affordability virtues, but with little real action to either improve affordability or allow the Government to be held accountable.

Firstly, the Government published its flagship Policy Statement on Housing and Urban Development, which is a followup to its much more specific and useful NPS on Urban Development from last year, which is forcing Councils to consider densifying their inner city suburbs. This latest GPS HUD was required by October 1 under the Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities Act 2019 and has to be reviewed every three years.

But yesterday’s statement is much fluffier and sets no specific goals or announces any new tools for the necessary housing supply shock. It is a broad waving of aspirational signals that fit into the motherhood and apple pie category. Here’s a sample (bolding mine):

“The homes and communities we live in are the foundation of our wellbeing and a focus on housing is a priority for this Government.

“All New Zealanders deserve to live in a safe, warm, dry home that they can afford. Aotearoa New Zealand faces complex housing and urban development challenges that have grown over generations.

“Responding to these challenges requires a strategy and direction to align the work of the whole system. This Government Policy Statement on Housing and Urban Development (GPS‐HUD) is intended to fulfil this role. It sets out a shared, aspirational vision and direction for housing and urban development in Aotearoa New Zealand over the next 30 years.” GPS HUD.

Except it then went on to leave out the detail of what success would look like at the end of that 30 years, or what some of the signs of heading in the right direction would look like.

“The GPS‐HUD is not intended to provide a detailed blueprint of all future activity. It takes a long‐term view, acknowledging that the context and environment will change over time. New initiatives, regulatory responses, and investments will be needed to meet changing needs, and ensure we stay on track to meet our vision.” GPS HUD

That meant it referred to some measures of affordability elsewhere in the world, but did not pick out any for the Government to judge others by or be judged by itself.

The most useful information in the document included that:

“Aotearoa New Zealand households spend the largest proportion of their disposable income on housing costs in the OECD. According to The Better Life Index 2020, our households spend on average 26% of their gross adjusted disposable income on housing, compared to the OECD average of 20%. Our unaffordable housing is resulting in too many people in housing stress or experiencing homelessness. In addition, the homes we do have often are not meeting our needs.”

“Tenants in public housing generally pay an income‐related rent of 25% of their income. This is considered affordable for public housing tenants. In contrast, some double‐income families with a mortgage may be able to support a higher proportion of housing costs relative to income.

“A common benchmark used internationally considers that housing that costs more than 30 per cent of income is unaffordable. However, banks will often lend to borrowers where mortgage servicing costs are greater than 30% of the borrower’s income.

At a local scale our population is growing and changing. By 2048 our population will exceed 6.2m people. Much of this population growth is projected to be in the larger urban areas, particularly in Auckland, where the population will increase by almost 650,000 more people.”

I subsequently asked Housing Minister Megan Woods whether the Government wanted to achieve either the 25% or 30% housing cost figures, or had any particular housing volume shortage view that would need addressing over the next 30 years. She said the Government didn’t have any particular targets. I’ve included the audio of the Q&A in the podcast above. You’ll get a sense from her answers of the Government’s vagueness.

No housing supply shock, funding tools or ambition

In essence, to simply keep up with the next year’s 30 years of population growth estimates (which only forecast just half the actual growth in the last 20 years), there would need to be at least 12,000 new homes built each year for the next three decades. That’s before any supply shock to drive down house prices, or to replace obsolete and expired houses, or to build different types of homes needed to hit our zero emissions targets.

There is no suggestion whatsoever in the document of using a supply shock to improve affordability, no definition of affordability to hold anyone accountable to, and no new infrastructure funding or taxation changes that would improve affordability (whatever that is). The only new (ish) idea is the idea of value capture rates, which would have to be imposed by Councils rather than Governments, which mean they would have to take any political pain involved. There is nothing to stop them doing this now, but only Queenstown has used them, and even then only in a limited way.

There were 70 uses of the word ‘affordable’ in this 56 page document and not a single target or tool to achieve it, whatever ‘it’ is. ‘Affordability’ was used once.

This was effectively a box-ticking and virtue-signalling document designed to meet the legislative requirements of the Kāinga Ora Act and give voters the impression the Government knows about the problem, cares about the problem, and is doing something. In actuality, it knows about the problem, but unaffordable housing is actually a political asset and it knows taking real action would damage its support among median voters. So nowhere near enough is being done. The best indication is in the price and rent inflation, and the actual announcements of changes on the ground, including last week’s confirmation of a halving of high-LVR lending, which will hit first home buyers the hardest.

Council planners, government officials, consumers and voters can safely avoid reading it. I read it so you don’t have to. You’re welcome.

Confirming the tax deductibility ‘shock’, but with a bonus

Three days before it was due to kick in (Oct 1), the Government finally announced the details of the changes in tax deductibility rules for interest costs on mortgages taken out by landlords. The indication in March of a four-year phase in was adhered to, but there were a few useful quirks.

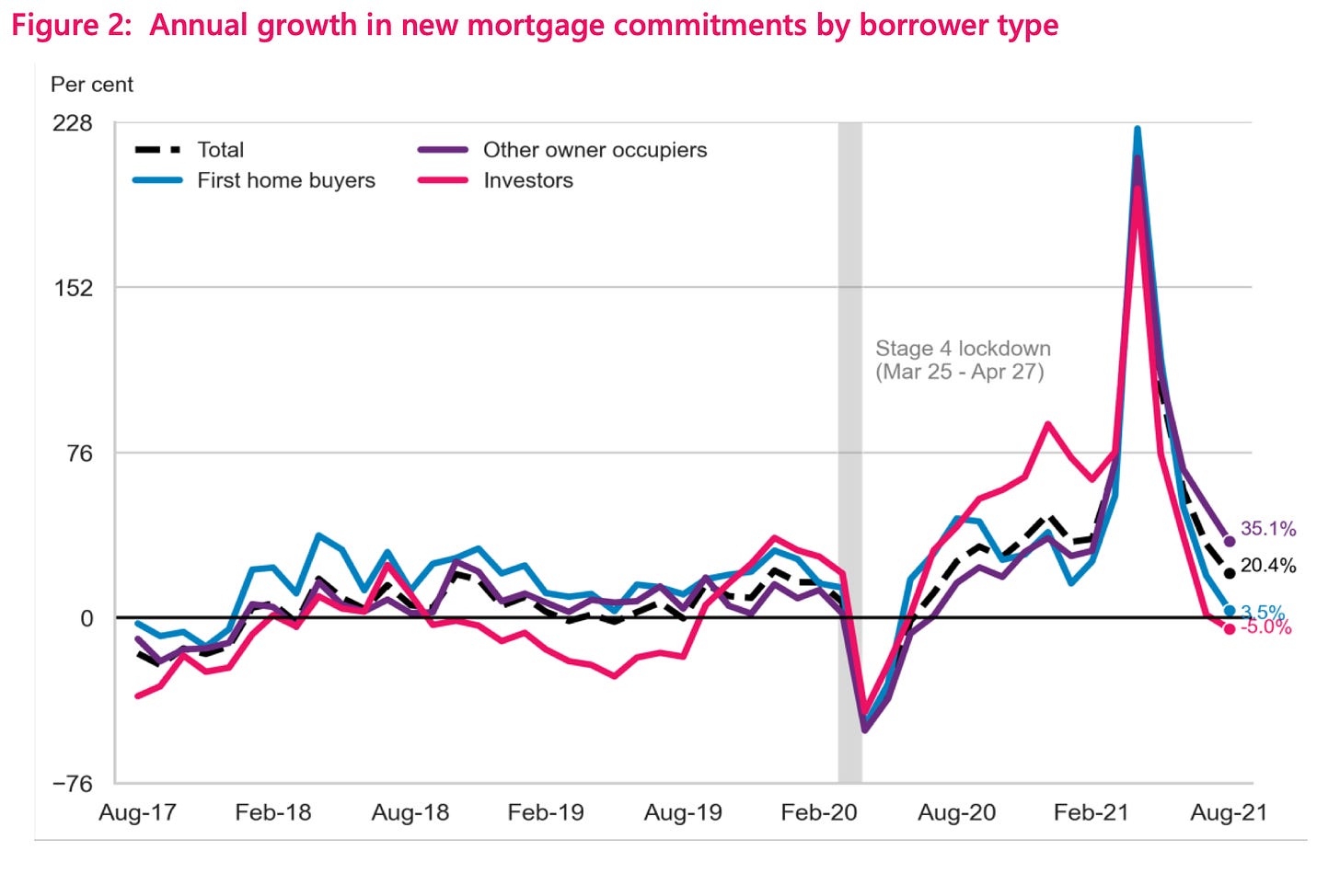

The announcement in March shocked many and caused a few to suggest it would reduce house prices, but in reality that didn’t happen. If anything, prices have accelerated in the last three months as listings supply has dried up.

Home owners and landlords know their capital gains are safe from tax, as long as they hold on to them for 10 years (rather than five years previously). If anything, the extension of the bright line test has taken properties out of the market to be on-sold, and lifted prices in the short term.

The rules will exempt people borrowing to build a new home and to service the debt on that home an exemption from the deductibility rules for 20 years, even if they sell in that time. It will add to demand for new houses from landlords, and mean there will be a 10-year trigger point for on-sales to other landlords wanting the benefit for the final 10 years.

I welcome any detail or comment from readers about more quirks buried in the regulations included in these information sheets provided by IRD, along with any other unintended consequences you foresee.

The unintended consequences

One potential unintended consequence is landlords loading up their debt into new properties, as well as leveraging as much debt as possible into new builds, which are exempt from the Reserve Bank rules about loan to value ratios. In theory, that would mean landlords being able to borrow 100% of the cost of a new build, or use a 5-10% deposit with equity withdrawn from other properties.

Given first home buyers are also having to use the LVR exemption for new builds to buy their own homes, this may well increase combined demand and therefore prices for new builds. It means they are more likely to be competing against investors for new builds and will be at the mercy of bank lending policies.

The move ramps up the pressure on the banks to take on the extra risk of high LVR lending on new builds and off-the-plan purchases, which banks already see as riskier than buying an existing home. They and the Reserve Bank will also be wary of storing up too much risk in property developments, which can blow up or dry up at the whim of a consenting officer or shortage of building materials or workers.

If there is a flood of lending into new builds, it may force the Reserve Bank to revisit its exemption for such lending, which has been one of the good features of the LVR controls, which have been in place for almost all of the last eight years (except for the six months or so after the first lockdowns).

Landlords already dominate new-build buying, and it may worsen

There has been a total of $53.4b of new mortgage lending in the six months since the beginning of March this year when the LVR restrictions were reimposed.

First home buyers and other owner-occupiers without rental property collateral got exemptions from the LVR restrictions, which includes new builds, of $2.96b or an average of $493m a month. That’s 5.5% of new lending.

Landlords got exemptions for $7.087b of new lending in the six months to the end of August this year. That’s an average of $1.181b per month and represents 13.3% of overall new borrowing. Combined, there was exempted high LVR lending of almost $10b in the six months for new home builds in the last six months, with most of it going to landlords. That’s 18.8% of new lending going up against inevitably risky homes.

This change in tax rules may have the perverse effect of encouraging even more borrowed money to pump up prices of new builds bought off the plan or brand new, and force banks to take more risks with their lending portfolios. That is the exact opposite of what the Reserve Bank is trying to achieve with its high LVR policy — to de-risk the banking system.

A wide perversity of potential outcomes

Presumably the banks will take action by themselves to avoid taking those risks, which means they will limit their amount of exempted high LVR lending to some percentage of new lending. A number north of 20% seems high and we’re almost there now. That process of rationing the riskiest credit would inevitably see banks favour landlords, given they have collateral and rental income galore in other properties the banks can take into account when assessing affordability and equity levels.

Tony Alexander pointed out today that is already happening (bolding mine).

“One thing we can expect is that existing investors will try to load as much of their debt as possible onto their new build purchases and away from existing properties. And we can expect a continuation of a preference by investors for new builds.

“The monthly survey of property investors which I run with Crockers Property Management shows that on average over the past four months, 49% of investors planning to make a purchase intend making it a new build. Considering that new builds each year only account for about 2.5% of the housing stock, this is an overwhelming bias towards buying new.

“Part of this very high desire to purchase new builds we can put down to the need to meet Healthy Homes standards. But its not going to all be plain sailing for investors in new builds.

Feedback from my various surveys shows that banks are tightening up their new build lending criteria, making applicants (investors and owner occupiers) allow for up to a 20% blowout in costs when calculations are made of debt servicing costs and whether the borrower qualifies for a loan.

“Banks are also increasingly watering down the proportion of expected rental income which landlords can count when calculating their ability to service a requested loan. In similar vein, some banks are heavily discounting rental income from flatmates anticipated by owner-occupiers looking to fund a purchase.” Tony Alexander.

So a policy designed to encourage new builds and give first home buyers a break, could end up screwing the scrum in favour of landlords again and starve new building projects of credit from banks. It may also boost the price of new builds, which would inevitably lift the prices across the market, given new build prices set prices at the margins, which tend to translate to higher prices across the board.

In summary, a policy designed to appear first home buyer and new-build friendly, could end up creating the perverse potential outcomes of favouring landlords, restricting lending for new builds and lifting house prices overall.

No wonder home owners still expect annual house price inflation of 6-7% and base their thinking on nominal house prices doubling every decade. At the current rate of growth, that would imply another collective $1t of tax-free and leveraged capital gains for home owners over the next decade. No wonder there is such FOMO gripping the market at the moment.

The simple facts are the Government is refusing to tax wealth, refusing to invest heavily enough in housing and transport infrastructure, and refusing to promise voters the necessary collective lowering of house prices to make any difference.

It’s refusing to pull all the levers because it knows the median voters that matter in any election want the current situation to continue ad infinitum. That’s why the PM has refused to countenance lower house prices and the Government is refusing to budge from its current adherence to the Public Finance Act’s requirement to reduce Government debt towards the 20% of GDP level seen by Treasury as the natural and ‘neutral’ level of Government debt that allows the size of Government to stay below 30% of GDP.

Ka kite ano

Bernard Hickey

PS. Please subscribe.

Share this post