TL;DR: Our latest wave of accidentally-on-purpose temporary worker migration is causing all sorts of grief, for some in the short run, and everybody in the long run.

Cases of fraud and overcrowding comitted against temporary workers in Auckland by ‘accredited employers’ was reported by Newshub’s Nick Truebridge here and here this week, but follows multiple reports by Lucy Xia at RNZ last month here and here, Steve Kilgallon at Stuff here and here, and Lincoln Tan at the NZ Herald here.

Under intense pressure to fill empty jobs and put a lid on wage inflation, the Labour Government rushed through a temporary work visa scheme last year that saw 27,000 employers self-declare they were nice employers and then bring in over 80,000 workers. After weeks of downplaying the issues, last night Immigration Minister Andrew Little was forced to launch a ministerial inquiry.

In the spirit of looking at alternative solutions, I suggest below what a joined-up and sustainably high-growth immigration and infrastructure investment policy would look like.

Paying subscribers can see more detail below and hear more in the podcast above. Join them in supporting our journalism in the public interest on housing, climate and poverty by subscribing in full. To paying subscribers: do you want it opened up? Please like and/or comment below.

Here’s an open, concious and high-growth strategy

Last night, Immigration and Public Service Minister Andrew Little announced an independent ministerial review of Immigration NZ's operation of the Accredited Employer Work Visa scheme, specifically relating to 'high level' concerns about 'opportunities for misuse and exploitation by third parties'.

So that's the Labour Government throwing Immigration NZ under the bus for forcing it to rush out a barely-policed employer accreditation scheme and Labour pulling hard on the inward migration lever at the same time last year to solve its political issues with inflation.

Massive and pervasive migrant abuse was always a risk when 80,000 visas were handed out to 27,000 employers in just over six months with the main 'checks' on both employer quality and the absence of locals to do the job being a few google searches.

The real issue here is the unspoken, unquestioned and unplanned-for instinct of both Labour and National Governments over the last 20 years to pull the cheap, easy migration lever to buy fast nominal GDP growth (and lower Budget deficits) and also avoid the necessary tax increases and extra investment spending to cope with 2% population growth per year...caused by the fast migration.

We need a proper debate about how to sustainably handle 2% a year population growth, and to consciously and publicly plan for that, after a political debate where the public agree. No more accidentally on purpose.

We should welcome 17 million by 2100, and plan for it

I'd love to see 2% population growth to 17 million by 2100 (and we probably won't have a choice because of climate change and the obvious political incentives), but to do that, you need to increase the share of GDP going into public and private infrastructure investment, business investment and R&D from ~20% of GDP to ~30% or so.

That requires more taxation to both do the investment and pay for the extra debt that is the best way to fund long term capital investments, and to change the incentives around private investment.

That's around 10% of GDP or $30b a year. At least half has to come from government. The best way to do both things -- to increase taxation and to switch the incentives from residential land investment to business investment -- is to bring in a wealth tax.

I'd prefer a broad-based and low-rate annual tax on the value of residential land, rather than a capital gains tax. It is the cleanest and fairest way to both tax wealth and leave in place incentives to increase business capital values (ex residential land) and keep the gains from capital income (ie increased capital values or sales of businesses).

It turns out a 0.5% residential land value tax would raise about $5b a year. That's a start. You could also do congestion charging and value-capture taxes to fund the infrastructure and manage demand.

But who would do it? And what should we target?

So how could this be done, within the context of the current arrangements for funding and delivery? We already have a model for such a change, which was successfully set up and used from the late 1980s to solve a fundamental problem in our economy. National and Labour collectively decided to tame the inflation of the 1970s and 1980s by creating an independent Reserve Bank tasked with achieving a goal set by Parliament and the Finance Minister, and then being allowed to get on with it.

The CPI inflation target was set at around 2% and then-Governor Don Brash pulled on the interest rate lever the crush inflation. In the process, the Reserve Bank helped drive the economy into a bad recession that lifted unemployment to almost 11% in 1991. But it was deemed a cost worth bearing and eventually it worked.

So what are the problems to be solved and what tools and independent roles could be created to do the same again, but for housing, transport and climate? And what would need to be agreed on a bipartisan basis to make it work?

Get housing & transport costs below 40% of income, plus carbon zero

We know our housing is unaffordable for most renters and unhealthy for many. It underpins most of our social, educational, health, crime, workforce and emissions reduction problems. Solving it by building warm, dry, carbon neutral homes on or near public and active transport routes and nodes that cost less than 30% of disposable income to rent or own solves both our housing and climate issues in one move.

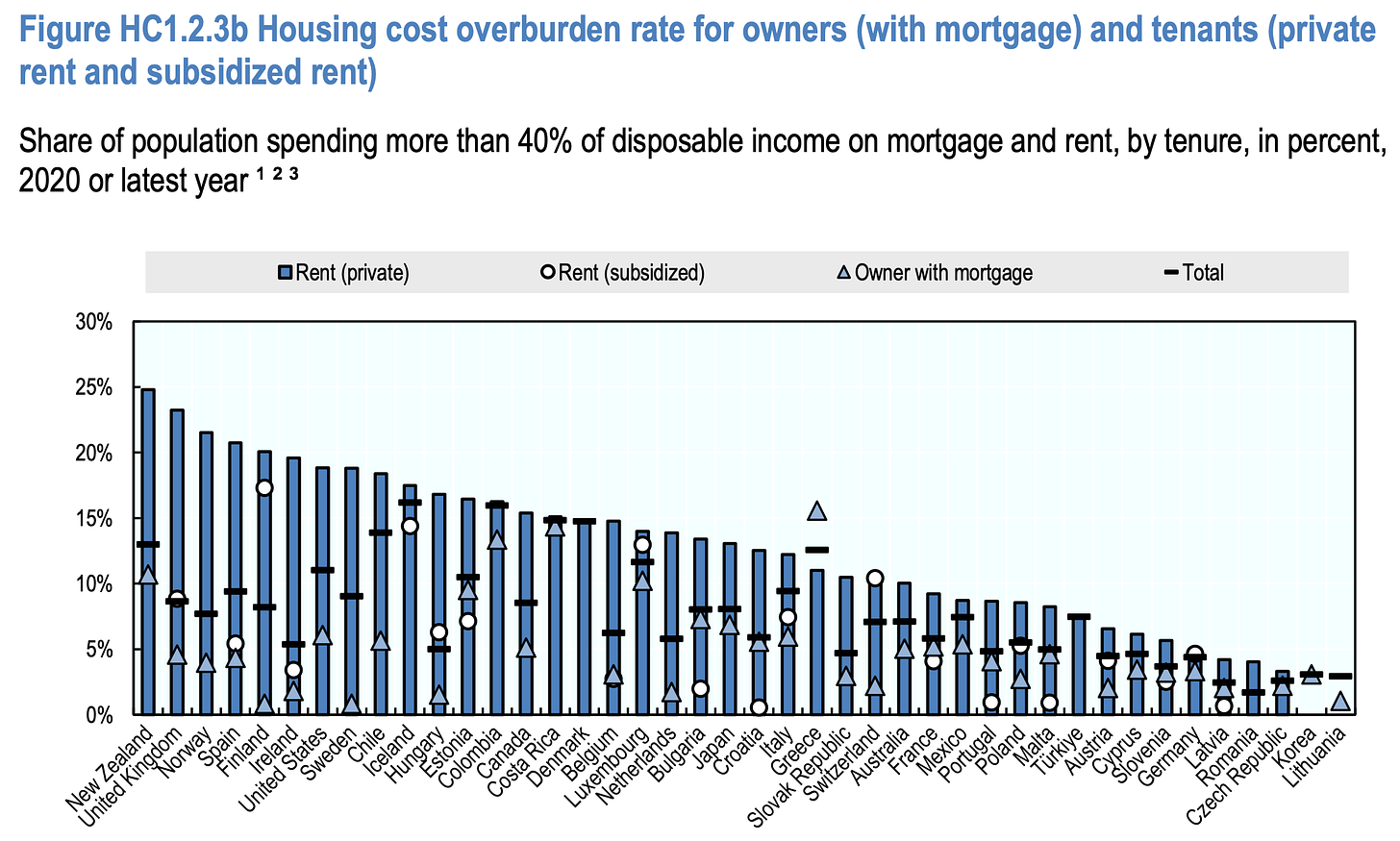

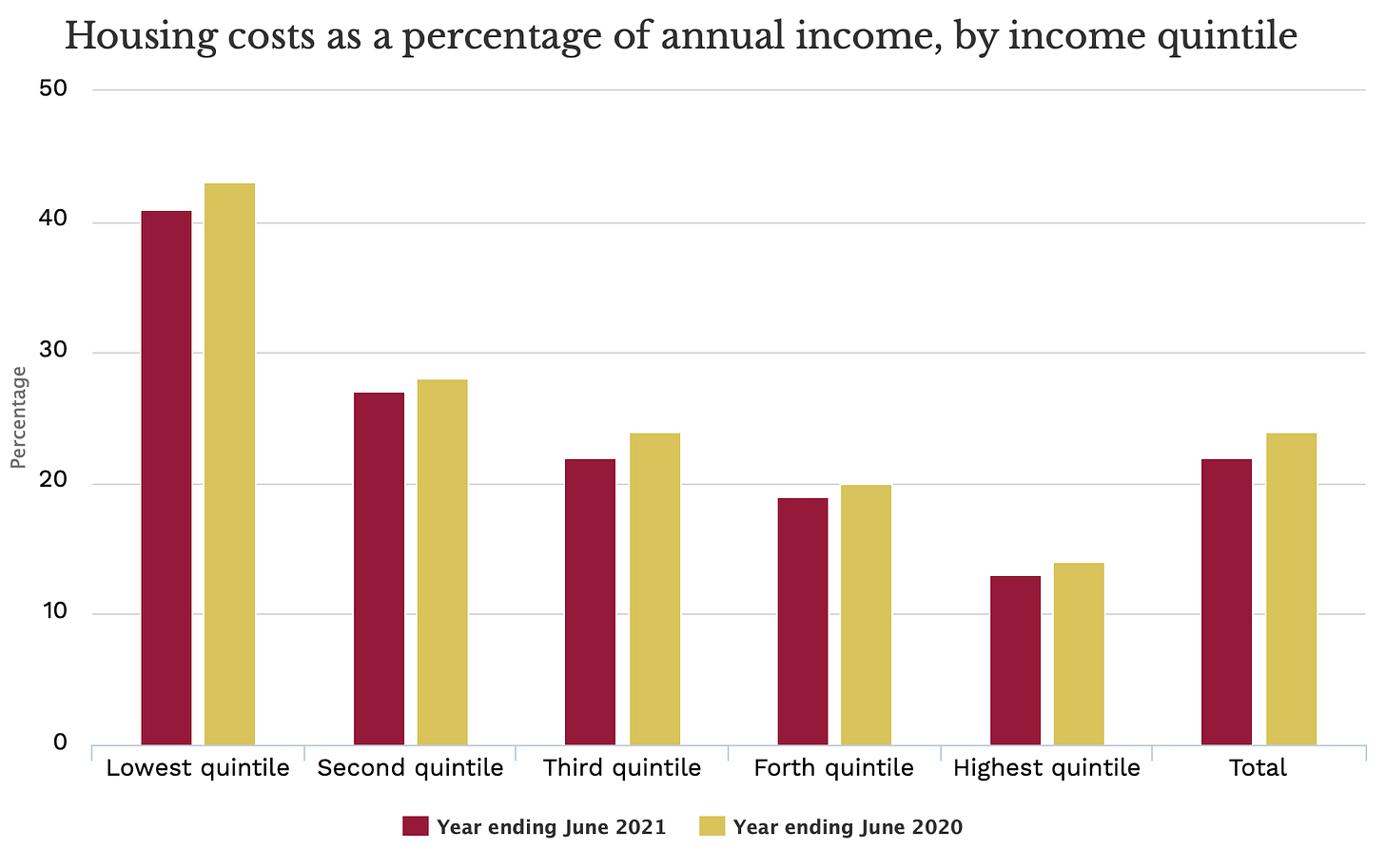

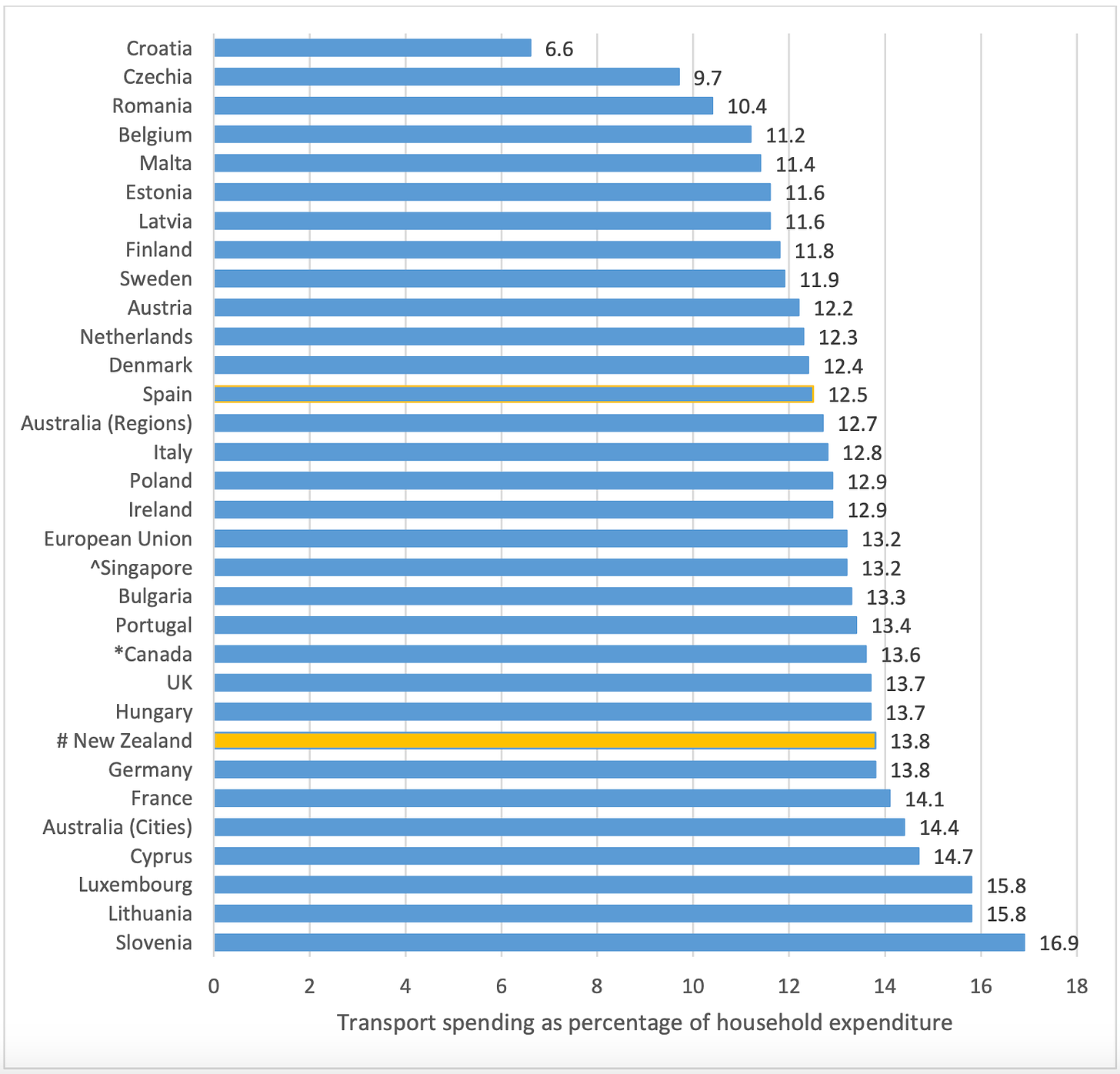

Reducing transport costs from around 14% of disposable income to 10% would reduce the combined cost under 40%, especially for those in the poorest 20% of the population. Currently, more than a third of that quintile are paying more than 30% of disposable income in rent. We have the highest share of stressed renters in the world.

Changing the transport network and redeveloping cities to make it easy and cheap for people to live near their work, school and leisure places is the task. The targets should be simple and intuitively obvious. Housing costs over 30% of disposable income are deemed internationally to be unaffordable and create financial stress. Transport costs should be less than 10% of disposable income and moving to all-electric buses, cars, trains, bikes and walking will achieve that, along with reduce emissions dramatically.

So the targets should be:

Housing (30%) and transport costs (10%) should be lower than 40% of disposable income for the lowest quintile income earners by 2050;

New housing and transport climate emissions should be lowered to zero annually by 2050; and,

Population growth from net migration should average 2% per year each decade to 2100.

So who sould have which tools?

National and Labour gave the Reserve Bank the right to independently use interest rates to achieve low inflation over more than three decades, with the main aim of removing this economically powerful tool from the hands of politicians. It worked, and still does.

We already have Kāinga Ora, Waka Kotahi, Te Waihanga (Infrastructure Commission) and He Pou Rangi (Climate Commission). A combined version, the Affordable Housing, Transport and Climate Commission, would have the assets, the tools and the ability to achieve those targets.

Those tools could include:

a residential land value tax to raise funds and service debt to achieve the targets above;

the assets upon which to issue long-term Affordable Housing and Climate Bonds that include incentives to achieve the targets above;

the ability to impose congestion and pollution charges to raise funds and manage demand;

the ability to plan and issue visas for permanent migrants to build help build and achieve these targets; and,

the ability to capture value uplift from land value appreciation linked to publicly-funded infrastructure.

An Affordable Housing and Climate Commissioner’s tool box

The Affordable Housing and Climate Commissioner would then be tasked with planning and achieving the path to affordable and zero emissions housing and transport by 2050 by using these tools, having to report regularly to Parliament, and be able to be sacked for non-delivery. They could plan investment and skills needs to achieve these across the cycle, using long term funding and demand management tools to achieve them, along with long-run skills management..

The aim would be to take the tools currently in the hands of politicians, road-building, pothole fixing, light rail building, debt cutting and migration settings out of the hands of politicians.

Doing this would require lots of workers, often from overseas.

It's should be a choice, not an accident on purpose...

Thoughts? Alternatives? Unintended consequences? Pros? Cons? I welcome more comments and suggestions from paying subscribers below. I floated this last night in our chat section here, which also generated 22 replies and counting.

Cheers

PS: I’ll have an AMA from 1pm today and we have The Weekly Hoon on at 5pm.

Share this post