Why our ute culture will eat our climate strategy for breakfast

New Zealand's climate and housing ambitions have become sound bites on a futile hunt for electorally painless policy trade-offs. Our love of suburban homes and utes will triumph without policy pain

New Zealand's climate and housing ambitions have become mere sound bites on a futile hunt for electorally painless policy trade-offs. Our love of suburban homes and double-cab utes is an enormously powerful cultural force. Changing that culture will take more than a few slogans and sensible spreadsheets. Politicians will have to impose pain and compensation in equal measure. Currently, there’s no suggestion either side of politics can or will do that.

Management guru Peter Drucker was reputed to have said: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” He meant that no amount of big-swinging, high-falutin’ strategy and top-down directions to change will overcome the entrenched culture of a company. That means the things people believe and aspire to, and the habits and practices used day in and day out. This saying is even more true for a society, an economy and a body politic.

New Zealand is currently in the strategising phase of dealing with its enormous housing affordability and climate change issues and politicians of all shades and sizes are doing plenty of swinging and falutin’. They are set to get eaten for lunch by an entrenched culture and love of suburban houses, double cab utes, SUVs, low taxes and ‘small target’ political strategies.

You wouldn’t know that if you listened to the great and the good making promises and pledges and talking about achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 without too much pain. The Climate Commission began the political year with its 188-page draft report on how to get there.

“After 12 months of considered analysis, the Climate Change Commission’s conclusion is that there are achievable, affordable and socially acceptable pathways for Aotearoa to take,” Chair Rod Carr said in releasing the report.

The Commission reckoned the economic cost of getting to carbon net zero could be as little as one percent of GDP or just $3b a year in the 10 years to 2035. However, that benign forecast rested on the assumption of a 30% fall in electricity prices after the closure of Tiwai Pt, the phasing out of petrol and diesel imports by 2035, a halving of transport emissions within 10 years, and the reduction of cow numbers by 15% by 2050.

Let’s look at each of those assumptions and the potential policies to make them work, along with the politics at play. The Commission was striking a hopeful pose and luckily doesn’t have to recommend specific policies, but each of those assumptions would entail overcoming entrenched interests, not to mention the day-to-day culture, balance sheets, household budgets and living arrangements of the ‘Team of Five Million’.

Rio Tinto and its power suppliers Meridian and Contact would have to agree to a shutdown and give up on the reliable hundreds of millions of dollars of profits they have made out of Manapouri’s power and the Tiwai Pt smelter over the years. Then there’s the other power ‘gentailers’ and their shareholders, who will want nothing to do with a 30% fall in wholesale power prices. The Government could spend $10b filling the Onslow Basin as a physical battery that drip-feeds power back into the market to keep prices down, but that’s simply a big taxpayer subsidy for power users, not to mention a self-inflicted act of value destruction on the Government’s 51% stakes in Meridian, Genesis and Mercury. Treasury would fight the Onslow idea tooth and nail from both a public debt and a shareholder value point of view.

Then there’s the projected halving of the vehicle fleet’s emissions over the next 10 years, which depends on the almost-immediate and wholesale shift to electric vehicles. This is where it gets very tricky in a policy and practical sense, and painful in a political sense. The Government’s first tentative nudge into this area in its first term gave it a flavour of just how painful and dangerous this area is.

The Labour-NZ First Government, supported by the Greens, suggested a ‘feebate’ scheme in mid 2019 where buyers of new double-cab utes would pay extra and that money would be transferred to buyers of more efficient petrol, hybrid and pure electric cars. It was a classic ‘revenue neutral,’ bright and apparently fair idea where the virtuous benefit from the punishment of the profligate: ie double-cab ute and SUV buyers subsidise buyers of pure and hybrid electric cars.

Labour’s ‘car tax’

National took one look at it and launched a social media campaign branding the idea as ‘Labour’s car tax’ that pictured the buyer of an old, used import petrol-powered Toyota Coralla paying $1,000 extra just so the buyer of an electric Porsche Cayenne could get a $1,000 discount. It was a political free kick cutting right to perceptions of fairness and apparent stupidity. Labour quickly dropped the idea as it dawned on them they faced a ‘nanny state’ type campaign where National aligned itself with families with utes in Te Atatu against Labour’s chardonnay socialists and their Green mates in Ponsonby and Grey Lynn. New Zealand First’s opposition was a convenient excuse.

This skirmish illustrates just how hard it will be to change fundamental things in our culture. Cars aren’t just machines. Suburban homes aren’t just collections of wood, brick and tiles on dirt. They represent our identities, our aspirations and are woven into the fabric of who we are as New Zealanders. People spend all their adult lives striving for a house with a backyard for the kids, a ‘flash’ ‘car’ that can pull a boat to the beach and room enough for a BBQ with your friends and family on a sunny, summer’s evening.

To halve carbon emissions from cars and utes requires massive changes in the way we live our lives, run our society and power our economy. Firstly, it would require a lot of trips in cities of less than 10kms that are currently done in cars, SUVs and utes to happen on buses and trains, or through walking and cycling. That means a lot more people living in denser housing close to city centres, and bus and train networks with taxpayer and ratepayer subsidies closer to $50b than $5b. That means a lot more apartment and townhouse living, and a lot more people choosing not to have their own cars. Given our current population growth rate of around 1.5% per year, it would also require a lot more vehicles to be smaller, lighter and electric powered.

Let’s look at what we currently buy and drive. Only two of the 20 most-sold new vehicles in 2020 were in that category: the Toyota Corolla and the Suzuki Swift numbers eight and nine. The other 18 were double-cab utes and SUVs, with the Ford Ranger, the Toyota Hilux, the Toyota RAV 4, the Mitsubishi Triton, the Kia Sportage, the Kia Seltos and the Mazda CX5 taking out the top seven spots. They are advertised as more than vehicles. They are expressions of identity; of family, of manliness, of sportiness, the outdoors and wide open spaces. It’s no accident that Barry Crump, the quintessential ‘kiwi bloke’ became the face of the Toyota Hilux. These are not just machines or houses. They are expressions of us and how we live.

The pace of the change needed is reflected in the Government’s proposals to reduce the average carbon emissions of new and used imported vehicles by around 40% to 105 grams per kilometre by 2025 by imposing car emissions standards on manufacturers. That’s just four years, and the new rules aren’t expected to apply properly until 2023.

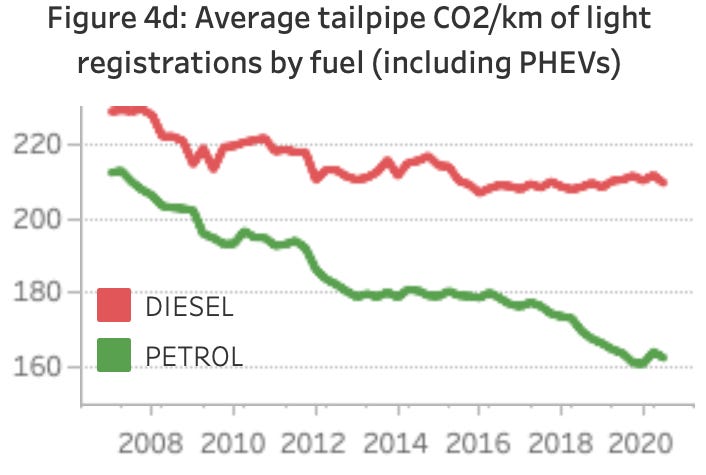

This chart shows how emissions of newly registered petrol vehicles have improved around 20% to 160g/km over the last decade, while diesel emissions (which are growing in line with the popularity of double-cab utes) have essentially been flat around 210g/km).

To bring the combined number down to 105g/km by 2025 would essentially require us to start importing all-electric SUVs and utes in massive numbers immediately. That would be impossible without massive subsidies for electric SUVs, or massive penalties for petrol utes and SUVs. To start with, there are no electric utes and the electric SUVs are around 50% more expensive. The Government has yet to detail how big its subsidies might be. It has been politically savvy so far in essentially pushing the political pain onto the importers. It can say, albeit without much credibility, that car dealers are responsible for the price pain, not the Government.

Higher taxes anyone?

The core issue is that to change emissions in the fundamental way forecast by the Climate Commission would require massive public subsidies and investments in electric vehicle subsidies, public transport infrastructure and higher density housing. That would require higher Government debt and taxes in the long run, including taxes on the rich to help the poor deal with higher transport costs and the shift from the suburbs into apartments and townhouses. No political party has even broached the possibility of such subsidies, debt or taxes. Labour’s main commitment in this term was to not introduce new taxes, especially on wealth, and to get debt back down to around 20% of GDP from a projected 36% by 2035.

The current trajectory is for politicians to try to muddle through in the hope they won’t be held accountable for the failure in the future to meet the emissions targets, or the more awful prospect of increasing transport costs by stealth and trying to regulate its way to new places to live. Both would hit the poorest families in the suburbs the hardest because they rely so heavily on cars to keep their jobs and make sure the kids get to school.

The political realities of such difficult choices will be more than enough to stop much happening, even as the Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern paints a bright picture of the future.

“We cannot underestimate a generation, full of angst and anxiety over the reality of climate change for them and their generation,” Ardern told Parliament in December as her Government declared a climate emergency. “And it is up to us to make sure that we demonstrate there is a pathway, there is a plan for action, and there is a reason for hope,” she said.

However, if she had been serious, she would have declared the Government would use its balance sheet to soften the blow of these changes on the poorest, and made clear it would be paid for by the wealthiest. But she did not. They were empty words for now.

"The current trajectory is for politicians to try to muddle through in the hope they won’t be held accountable for the failure in the future to meet the emissions targets, or the more awful prospect of increasing transport costs by stealth and trying to regulate its way to new places to live."

The can has been kicked down the road and off the cliff and no one can face it, hence our total lack of preparation for the unfolding collapse.

Canadian environmentalist William Rees brilliantly summarised our predicament "The Scientifically Necessary is Politically unfeasible, the Politically Feasible is Scientifically Irrelevant".

https://kevinhester.live/2019/09/05/collapse-the-only-realistic-scenario/

So many things we need to do are currently politically unpalatable (ie. electoral suicide) So the vital thing to do is to have the vision, determination and wisdom to start from the other end: make the things we need to do politically acceptable, if not politically necessary. That requires both informative persuasion, and doing subtle things that, added together, change enough people's minds to make a difference. One that springs to mind is ignoring the motor trade lobbyists and legislating that all vehicles must permanently display a 'pollution' sticker next to the WoF, with a simple visual scale like we get on fridges when we buy them. Another would be forcing IRD to enforce the rules on the tax preferential treatment for double cab utes - everybody knows they are actually a massive tax rort with many 'company' utes used for the school run and boat ramp and some 'signage' so subtle or small as to be imperceptible. It would start to chip away at the desirability if more people had to pay the full cost. There are plenty more.....