Real GDP per hour worked stagnated since 2012

High migration and rising land values disguised average growth in real GDP per hour worked of 0.35% per annum since 2012; Per capita GDP down 2.1% in last six months

TL;DR: Politicians squabbled and economists quibbled over GDP figures this week that appear to show Aotearoa dipped into a technical recession in the March quarter of this year.

But the real story is much worse and basically unchanged for a decade at least: our real output per hour worked has stagnated since 2012 because of a lack of investment in our infrastructure, houses, transport, health, education and people.

Instead, we have disguised our relative decline with the fastest migration-led population growth in the developed world, a starvation of maintenance and investment in our capital stock, and forcing the collateral damage on our environment, health system, justice system and social fabric off into the uncosted and unmeasured future.

If a business that was properly accounted for and audited had performed as ‘Aotearoa Inc’ has performed over the last ten years, it would show some revenue growth and cash surpluses, but ongoing net losses because depreciation was not matched by capital spending. The net worth of the ‘company’ fell sharply because of fast-growing long-term emissions liabilities, health spending liabilities and a degraded ‘capital stock’ in the form of less-healthy people and a less-healthy environment.

It’s been a two-decade-long exercise in kidding ourselves by importing temporary labour to cover up the lack of investment in our own people and capital, which would have allowed growth in output per hour worked and improved our ‘capital stocks’ in healthier and more productive people, cleaner air and cleaner water.

In essence, Aotearoa Inc grew GDP over the last decade by having more people work longer hours and by consuming existing and future assets faster than we created new ones, while also creating larger long-term liabilities. But we (or at least landowners) felt we had become richer because the ‘value’ of our land for mortgage validation purposes doubled to around $1 trillion. See more below

Usually, I put in a paywall for paying subscribers at this point in the email newsletter. But I want to experiment until the end of June with publishing everything to everyone immediately to see what happens with subscription rates, revenues and email opening rates. I want to thank paying subscribers in advance, who are still the only ones able to comment and get access to our very active chat section and webinars. Join our community by subscribing in full to support my journalism in the public interest about housing (un)affordability, climate change (in)action and poverty (not enough) reduction.

The ‘P’ words mean much more than the ‘R’ word

This week’s ‘news’ and debate has all been about the meaning of the ‘R’ word for our political economy. The key questions from our politicians, economists, business editors and talk-show hosts have been:

will the technical recession in the March quarter1 make Labour or National more or less electable?;

will the June quarter GDP figures out on September 21 be the deciding factor in the October 14 election?;

will this recession make the ‘cost of living crisis’ for the ‘squeezed middle’ much worse?;

will the recession end quickly enough and be shallow enough for it not to hurt employment too much?;

is this the recession Te Pūtea Matua (The Reserve Bank) was trying to engineer?; and therefore,

will it give the central bank enough comfort to cut interest rates soon?

None of the discussion about this recession really matters in the long run for the actual economy and society in general. We should be talking about the ‘P’ words, not the ‘R’ word. Productivity first.

“Productivity isn't everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman.

Productivity is hard to measure, but a broad proxy and the one that is most closely aligned to real hourly wages is GDP per hour worked.

World Bank data shows New Zealand’s economy has generated a total of 3.5% growth in real GDP per hour worked in the last 10 years. That’s 3.5% in total. Not per annum. The average of 0.35% per annum pales in comparison with the total real GDP growth we reported of 33.7% over that decade-long period, or an average of 3.37% per annum. We thought we were doing OK, especially because that 2012 to 2022 period included Covid and the aftermath of the Christchurch earthquakes.

Woohoo. Never mind the quality. Feel the width.

And remember, the 33.7% growth in total GDP is AFTER taking out the effects of inflation, especially in 2021 and 2022. Nominal GDP grew 69.6% or an average per year of almost 7% over the last decade. Woohoo. Never mind the quality. Feel the width.

Actually, we did appallingly on a GDP-per-hour worked basis, as this chart below shows.

There are hints of this underlying quality problem in the national accounts released this week, with per capita real GDP (which doesn’t take into account the hours worked) falling 2.1% in the December and March quarters combined. That per-capita recession is almost three times bigger than the total recession. That’s because we rapidly grew the population again over that six months.

Under economic and political pressure, the royal ‘we’, which includes employers, the Labour Government and the Opposition, fell back on what we’ve come to know and love best over the last 20 years. We pulled the migration levers. Employers begged the Government to open the taps, and it did. The Opposition would have opened them even wider, and may well get a chance to do that within five months.

So where did all the productivity talk go?

There was a time when politicians from both sides of the house talked a lot about productivity. Then-Finance Minister Bill English talked a lot about at the beginning of the ten-year period. Then-Opposition Finance Spokesmen (there were a few from 2011 to 2017) talked a lot about it towards the end of the National Government when it became apparent the productivity was not showing up.

Finance Minister from 2017 to 2023 inclusive, Grant Robertson, talked about it a lot during the 2017 election debates, but hasn’t mentioned it much since. There has been much more talk about wellbeing, which is harder to measure and actually hasn’t been measured much at all, particularly in the national ‘balance sheet’s’ produced by Treasury for the Budget process.

Politicians and editors focus mostly on the Budget Deficit and the Government’s borrowings when they talk about ‘economic management’ and ‘fiscal prudence’. In effect, they are only look at the Government’s cash-flow and ‘profit and loss’ statements. They hardly ever look at the balance sheet, which measures changes in the measured assets and liabilities of the Government or Crown, if not the country as a whole.

As any investor, owner, manager or director knows, the balance sheet, the profit and loss and the cashflow accounts need to be looked at as a whole. Cashflow can be made to look exceptional by not investing spare cash in maintenance or building new assets, or by juicing sales and profits by pumping discounted sales or trashing future earnings by slashing costs now. The profit and loss accounts can be made to look special by revaluing assets incorrectly or under-valuing changes in intangible but very real liabilities.

All three sets of accounts, cashflow, profit and loss and the balance sheet, need to be examined to assess performance of an entity such as a Government or company. GDP is a bit different from them all because it measures total output, spending and income in an entire national economy. It doesn’t measure, for example, changes in the capital stocks of human capital (health and skills) or physical capital (clean air, water, soil), and doesn’t measure future liabilities.

So what is the best measure of performance? As Krugman says, it’s always, always about productivity. It should also be about our future liabilities, be they immediately measureable in the form of national public and private debt to foreign entities2, or the less-easily-measurable, such as national emissions liabilities and a growing mental health and obesity-driven liability looming in future health costs.

The productivity talk went the same place it always goes. Down in flames in the CGT debate

Now the productivity debate is either conveniently side-swiped into academic and policy-wonk circles, or vaguely hinted at with talk of ‘bread and butter’ issues and ‘getting our mojo back’3, whatever that means. Talking about productivity seriously would require a serious debate about removing the effective tax advantage for owner-occupiers to buy more residential land, rather than invest in real businesses or pay tax for real infrastructure and public services than improve productivity.

The smart money knows productivity and real wages don’t matter either, because they understand the politicians and median voters are too smug or scared to touch the issue of taxing residential land or capital gains on that land occupied by those voters.

It’s always, always about our housing market with bits tacked on

The smart money has been looking past the GDP numbers and the real output per hour worked figures and straight at the housing market, which is showing pleasing signs of ‘green shoots’ because of a lack of new housing supply coming on stream and plenty of new warm bodies coming into the country needing a roof (or maybe a tent, or caravan or motel or boarding house) over their heads.

The prospects of lower interest rates, thanks to the recession, are helping too. When the actual way to get wealthy in Aotearoa is to buy residential land and sit on it to win untaxed and unearned gains from falling interest rates and mismatched infrastructure and migration policies, then real GDP and real wages don’t matter.

The only things that matter are interest rates, house prices, migration rates, the scale of the housing supply shortage and tax policies. Why improve output per hour worked, when the only way to actually get rich is to get a deposit somehow, borrow a shedload and buy with your ears pinned back? And then hold.

‘Recession smershession. I want to buy more land now’

Here’s what mortgage brokers, real estate agents and rental property investors have been saying in recent weeks in surveys done by independent economist Tony Alexander, including:

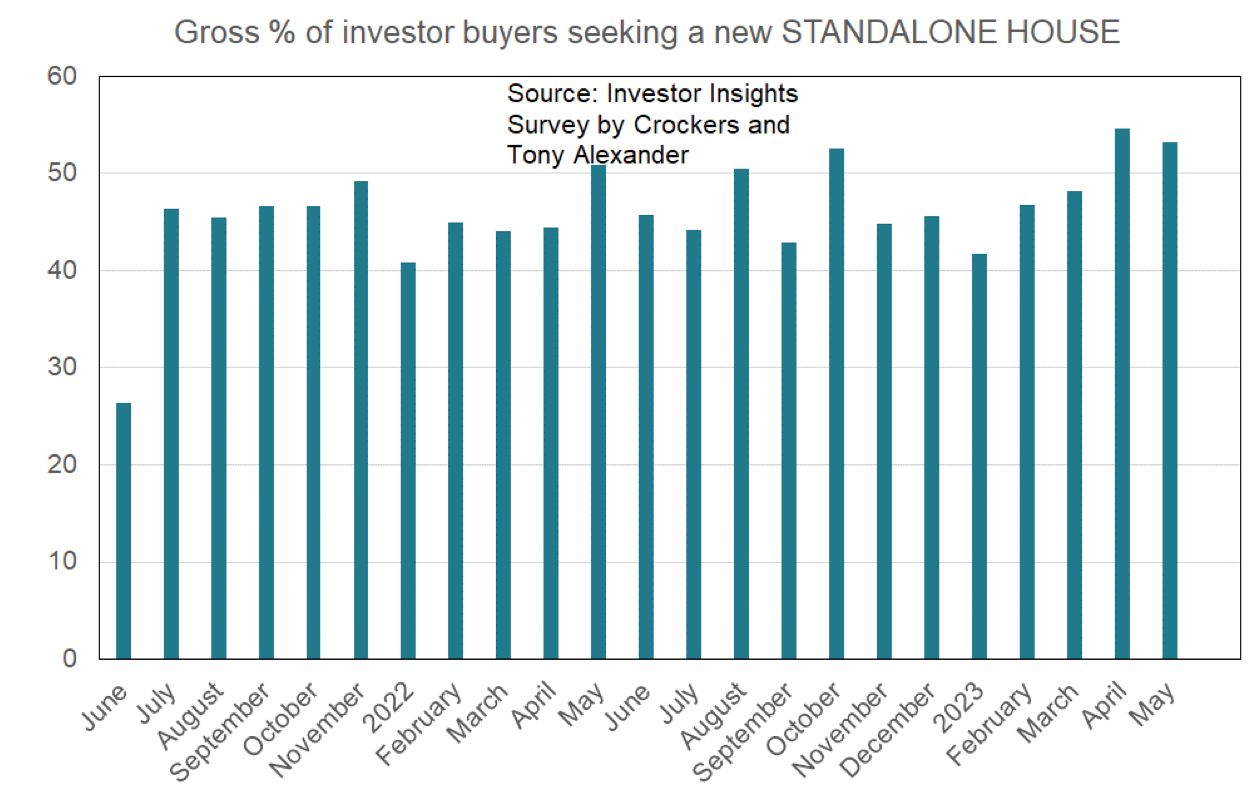

More than 50% of rental property investors want to buy a new standalone home (which is exempt from interest serviceability restrictions), up more than 10 percentage points during the ‘recession’ quarter;

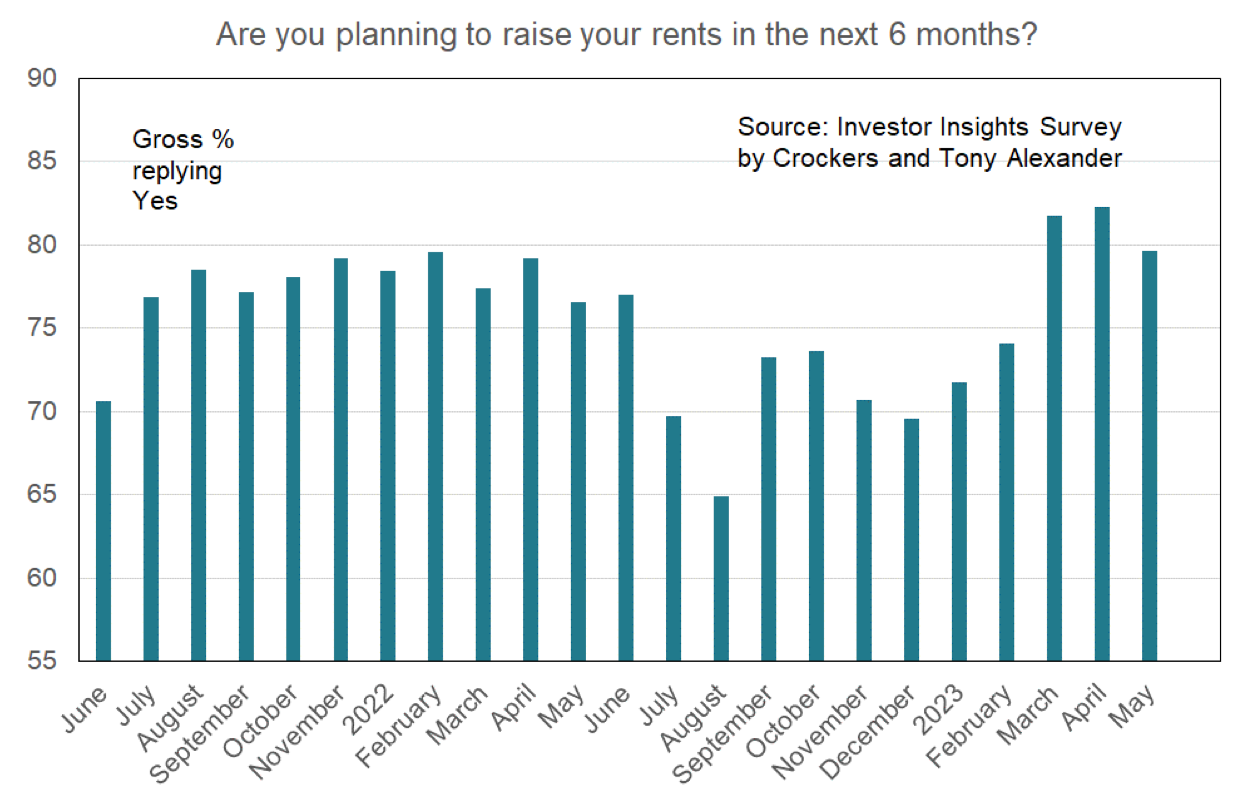

Nearly 80% of landlords planning to raise rents in the next six months, despite economic activity receding in the March quarter;

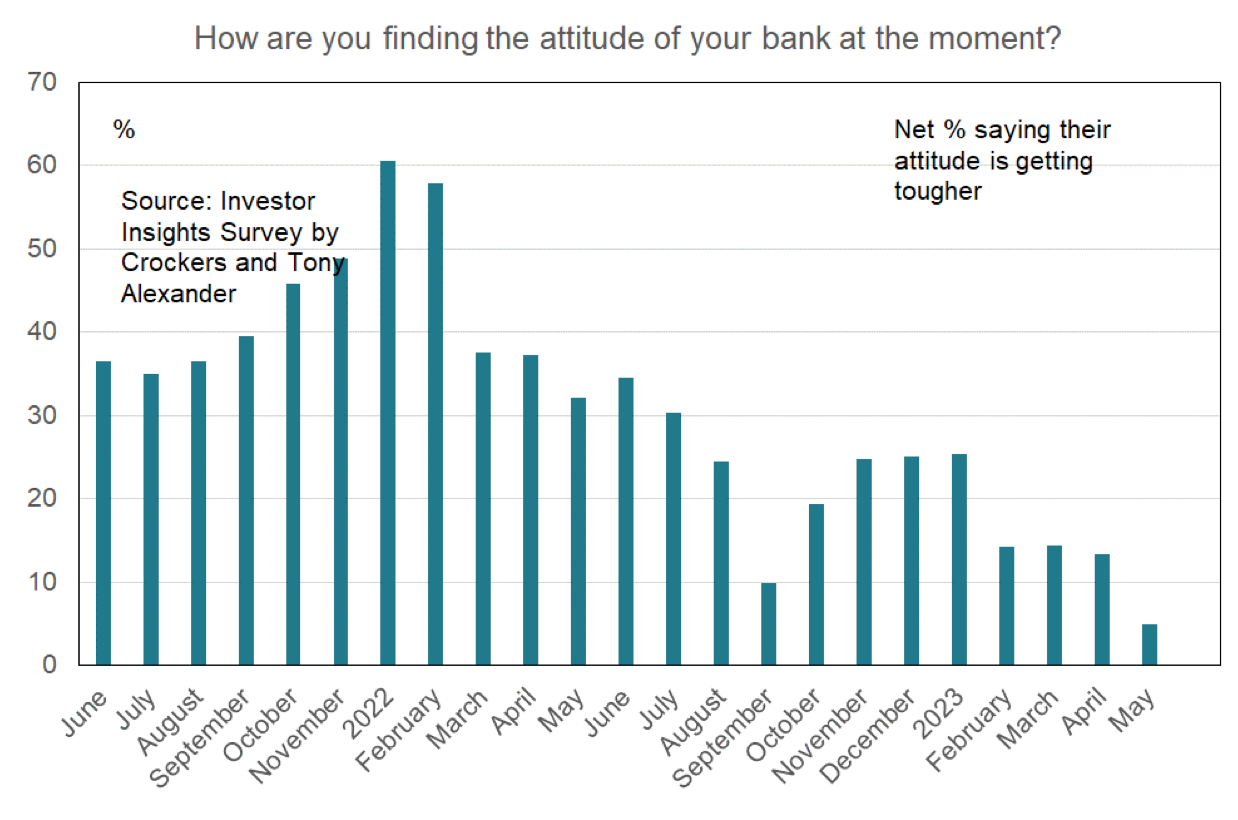

Less than five percent of landlords saying their banks are tougher to deal with, down from 25% at the beginning of the year and 60% at the height of the CCCFA scare and the start of rising interest rates in late 2021, and despite a recession this and higher interest rates usually making banks more nervous4;

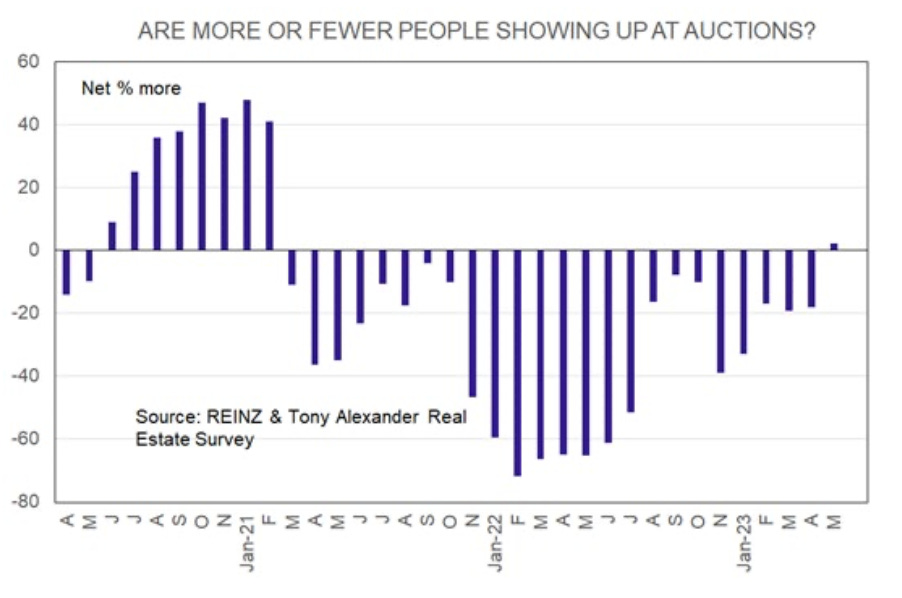

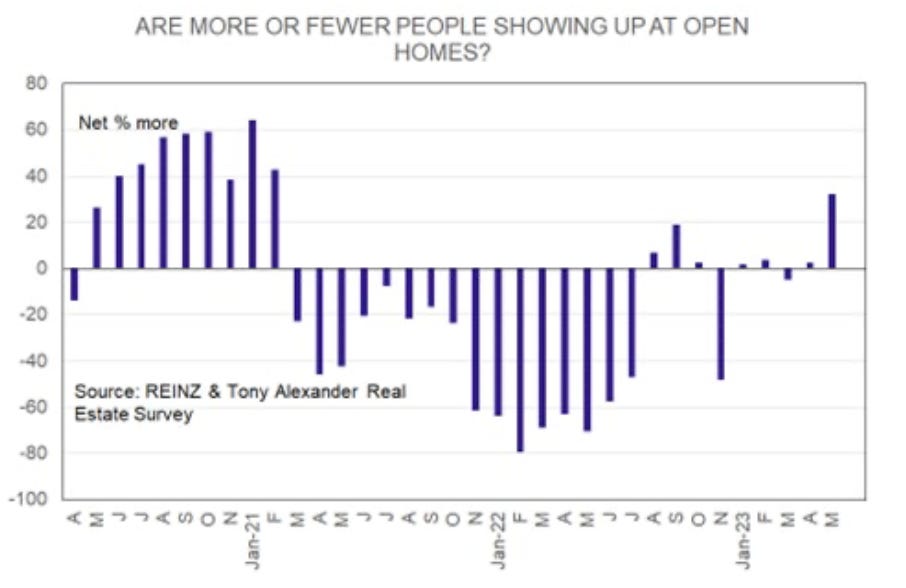

Real estate agents reported more people showing up at auctions in May for the first time since February 2021, despite higher interest rates and the economy ‘slumping’ into a recession;

Real estate agents reported a sharp rise in people turning up to open homes in May to levels not seen since February 2021;

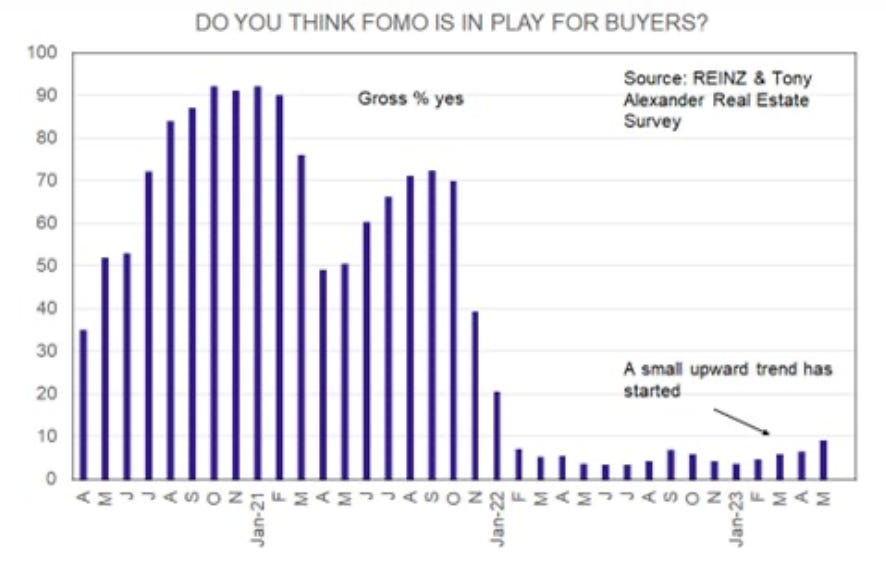

Real estate agents reporting a clear upward trend in buyers showing signs of FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) rather than FOOP (Fear Of Overpaying); and,

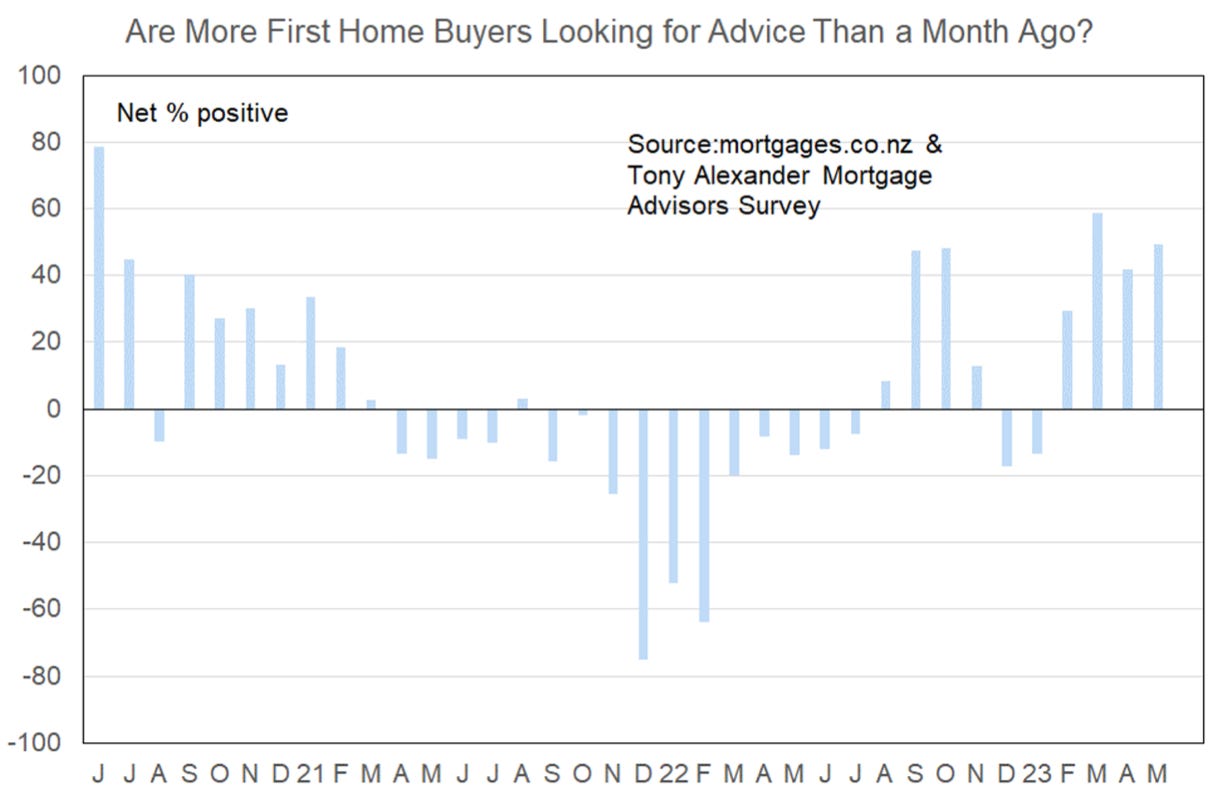

Nearly 50% of mortgage advisers reporting more first home buyers looking for advice in May about borrowing to buy homes, which is back in line with levels seen during the boomiest periods of Covid, when the commentators were all worried (in theory) about a recession.

Until we talk about changing taxation and investment incentives, GDP is irrelevant

New Zealand doesn’t invest enough in infrastructure and in its businesses and R&D because it makes more sense to invest spare cash in leveraged land generating rental returns in a supply-constrained market. Just ask the Opposition leader. The self-professed business expert promoting more ‘business hustle’ invested his own surpluses in seven homes.

The ‘smart money’ may be talking loudly about a recession and ‘unfriendly’ Government for businesses, but watch what it’s actually doing: piling more equity into leveraged land.

Here’s why our productivity record has been so poor for the last decade, and the previous decade, although less bad: we are a capital-light nation of property investors, even if the only property we own is our own home. Changing that requires fundamentally changing the incentives. That means some form of wealth or land or capital gains tax on the family home, which is the base for most investment, spending and political decisions.

Until that changes, reading the national accounts or the Budget is mostly irrelevant, particularly because they don’t include the very real, very large and very unmeasured liabilities being built up for future generations to pay in the form of emissions liabilities, worsening air and water quality, worsening mental health and obesity, and the opportunity costs of not improving productivity.

I’d like to be surprised, but so far, this election debate is shaping up as one between two main parties trying to avoid talking about the ‘P’ words (productivity and property), and instead talking about the ‘R’ word, the ‘W’ word (Wellbeing) , the ‘M’ word (‘Mojo’) and plenty of ‘C’ words (coalitions of cuts and chaos).

And never, never, never mentioning the ‘T’ (tax) word in conjunction with the ‘L’ word (Land.)

Ka kite ano

Bernard

PS: For fun, here’s a video I took yesterday of a skink in a rock wall on the Greek island of Andros. Fun times. Hope you’re enjoying our productivity!

Total real GDP fell 0.1% in the March quarter, adding to the (revised) 0.7% fall in the December quarter and therefore satisfying the technical definition of a recession, which is two consecutive quarters of negative growth.

Perhaps ironically, net debt actually fell to 46.8% of GDP in the March quarter from 47.1% in the December quarter and is down from 66.6% of GDP ten years earlier, the external accounts released by Stats NZ this week showed, although they don’t include the potential emissions liability from the Paris agreement of up to $27 billion by 2030, as projected by Treasury last year.

National Leader Christopher Luxon diagnosed New Zealand’s problems this week as something to do with ‘mojo’, telling RNZ: "I think New Zealand is a country of endless potential, it's the best country on planet Earth, we've got amazing people, we're in an exciting part of the world in the Asia-Pacific region." But he said the country had gone backward under the Labour government and it needed to "get its mojo back". "We want to be a government that's going to turn it around and get some ambition and some aspiration and some positivity and optimism in the country going forward."

There’s other things happening here too. The CCCFA was just relaxed. The Reserve Bank just relaxed LVR rules and also proposed this week to lower capital requirements for first home buyers. No wonder banks are saying yes, first home buyers are going to open homes and landlords are keen to buy land-and-house packages exempt from interest deductibility rules.

Where does one start? It's worse than basically nil growth since 2012. Its nil growth since 1996. More than one generation. I honestly can't see anything changing it. I've given up. Skilled people leave and we bring in equally skilled people from poorer countries. The annual rate of immigration at 2% of total population (highest in the OECD) means that within 35 years half of us will be represented by individuals who have emigrated from those other countries. Less than 50% of New Zealanders living in New Zealand will have been born here and of those 50% that have many will have just one generation of Kiwidom culturally behind them. And that means we'll change in many ways quite profoundly. Nothing wrong with an explicit choice to do that in order to make a better society - and it may - but to do so simply to continually elevate the price of houses is the path to a dysfunctional society.

Two options

Emigrate

Get TOPS above 5%