Long stories short, here’s the top six news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa-NZ this week, and a discussion above between Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer:

Scientists are not entirely sure why sea surface temperatures have been accelerating so quickly over the past year, at the same time as air surface temperatures.

A study on the effects of storms in the Southern Ocean has found they are triggering an outgassing of carbon dioxide, which may affect their ability to absorb carbon in the future. Nearly half of all current ocean carbon uptake is believed to occur in the Southern Ocean.

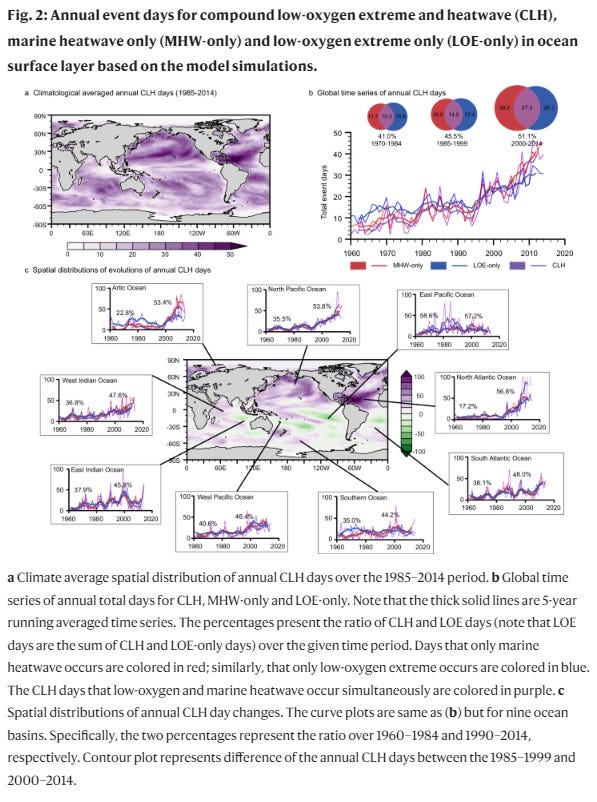

Another study in the journal Nature found that marine heatwaves caused by climate change are triggering low-oxygen extreme events. “[O]ur findings suggest the ocean is losing its breath under the influence of heatwaves, potentially experiencing more severe damage than previously anticipated.”

Finally, another study has found that just 1.5°C of subsurface ocean warming triggered repeated Antarctic Ice Sheet (AIS) collapses during the Pliocene, a period considered a good analogue for current and future sea level. These AIS collapses contributed up to 25m of sea level change.

Understanding why oceans are ‘weirdly hot’ at the moment, the subject of this analysis in NPR, has enormous consequences for what we might expect in the future. A possible link to shipping pollution is gaining credence.

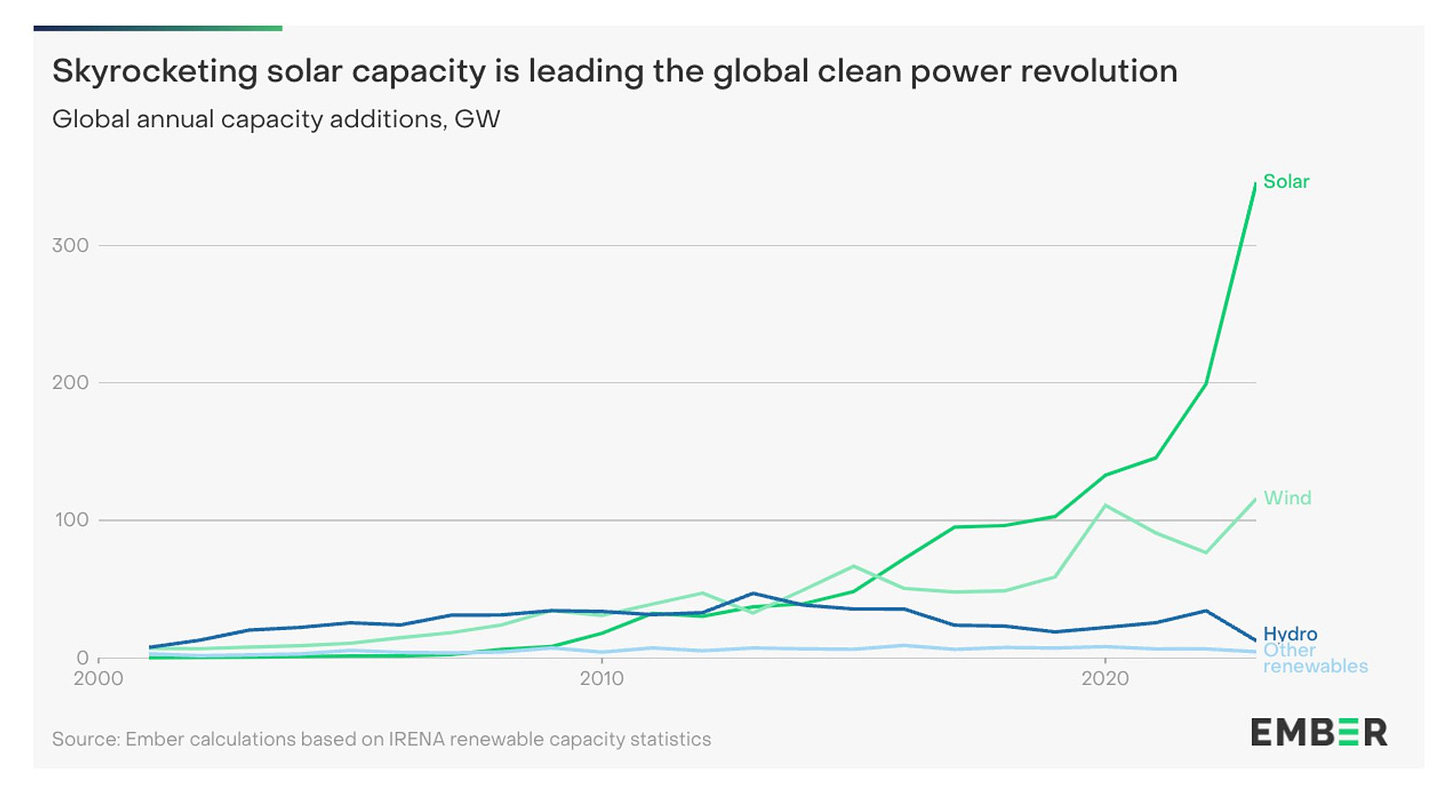

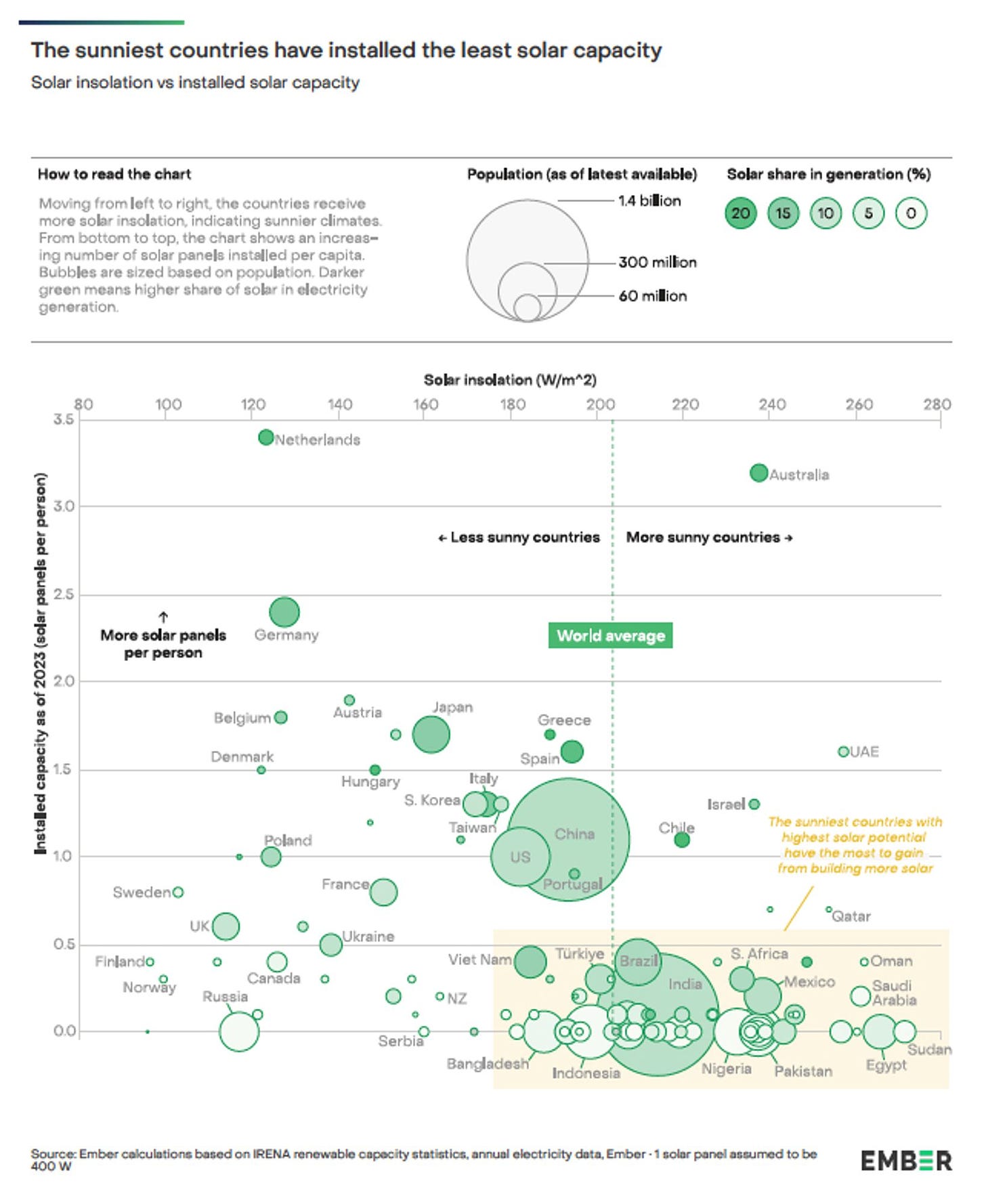

Energy think tank Ember’s 2024 Global Electricity Review shows the meteoric rise of solar capacity, but also highlights the fact that related efficiency gains would be much higher if they were being built in sunnier countries. This suggests that OECD countries should invest more in climate financing for solar installations in developing countries, while focusing on demand-side reductions in fossil demand at home (although that’s not exactly how Ember put it).

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the video and podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

1. Scientists stumped over sea surface temps

A series of big papers on ocean heating has come out in the past few weeks, likely in response to the past year’s record mean ocean surface temperatures.

The oceans play a significant role in stabilising earth’s climate, absorbing heat from global warming, but also feeding that additional energy into stronger storms, that intensify more quickly. Any change in the capacity of oceans to absorb heat has big implications for the rate of global warming. According to a blog on pbsnc.org,

It’s likely the warmer Earth and air temperatures are contributing to the warmer ocean temperatures, but scientists don’t know precisely why sea surface temperatures have climbed so high so fast.

While air temperatures are warmer, water has a greater capacity to absorb and store heat. In fact, the ocean has absorbed about 90% of the heat created by global warming.

“It takes a lot of heat to raise water’s temperature, and I do fear there may be something else going on that is causing a long-term change in sea surface temperatures we hadn’t predicted,” said John Abraham, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, who studies ocean temperatures.

Far from being immune to this, sea temperatures in some areas around Aotearoa New Zealand have been outstripping global average temperatures three-fold, as we reported last month. Data from Stats NZ show coastal water temperatures increasing 0.19-0.34°C per decade. This would have contributed to the strength of Cyclone Gabrielle last year.

2. Storms tipping the carbon scales

A study on the effects of storms in the Southern Ocean, of which there are many, has found that they trigger a release of carbon dioxide.

In addition to absorbing 90% of earth’s heat, oceans also take up 25% of the excess carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by human activity and nearly half of this carbon uptake is believed to occur over the Southern Ocean. To date, the exchange of carbon between the atmosphere and ocean, particularly in this region, has not been well understood.

The finding that “storms tip the scales in the air-sea exchange of carbon in the Southern Ocean” in a process known as outgassing, is critical to modelling the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon and to predict the effects of climate warming in the future.

3. The ocean is losing its breath

Another study, published in the journal Nature, found that marine heatwaves caused by climate change can trigger low-oxygen extreme events.

Oxygen levels in seawater are a crucial element in sustaining biological survival. It is known that warming oceans are losing oxygen, primarily due to human activity.

According to the study authors “[O]ur findings suggest the ocean is losing its breath under the influence of heatwaves, potentially experiencing more severe damage than previously anticipated.”

Source: The ocean losing its breath under the heatwaves

4. Insights from the far distant past

Another big study this month has found that just 1.5°C of subsurface ocean warming triggered periodic marine ice sheet collapses in Antarctica during the Pliocene era, contributing up to 25m of glacial-interglacial sea level change.

On the basis of CO2 concentrations and global temperatures, the Pliocene is believed to provide a good comparison for current and future sea level and climate and is thus important for modelling the impact of Antactic Ice Sheet (AIS) dynamics on sea level projections. That puts the speed of ocean warming we are currently seeing into perspective.

5. The role of shipping in heating the sea

Understanding why oceans are ‘weirdly hot’ at the moment, the subject of this analysis in NPR, has enormous consequences for what we might expect in the future.

One leading explanation is that the reduction in pollution from ships is playing a role.

This is a core element of James Hansen’s claim, outlined in the paper ‘Global warming in the pipeline’, which suggests that climate scientists have been underestimating climate sensitivity and that an acceleration in heating is occurring.

Another recent study supports his contention that reductions in ship sulphur emissions since new regulations came into force in 2020 have accelerated global warming. Hansen famously warned that “under the present geopolitical approach to GHG emissions, global warming will exceed 1.5°C in the 2020s and 2°C before 2050”. The evidence is continuing to stack up in favour of his view, with ocean heating providing a critical element.

Some climate scientists, according to an article in Bloomberg, are now expecting temperature spikes that set new records to occur more frequently in future, with bigger jumps from one high to the next. Erich Fischer, a climate scientist at ETH Zurich was lead author of a paper in 2021 that predicted “record-shattering extremes, nearly impossible in the absence of warming” that proved almost immediately prophetic.

As new extremes arrive, Fischer predicts previously rare high-end temperatures will become more commonplace. A 1-in-1,000-year heat wave any time between 1951 and 2019 will have shifted to a 1-in-100-year event by around 2020, according to his study. That not-so-unusual heat wave will move again to a 1-in-40-year event in the mid-2020s.

6. The Ember report: air con boom and solar inefficiencies

Demand for air conditioners is contributing to an anticipated surge in energy demand in 2024 according to energy think tank Ember’s annual Global Electricity Review.

Demand for key electrification technologies that replace fossil fuels with electrification, in particular EVs and heat pumps, have contributed 27% of total demand growth in 2023. These contribute to a net decrease in energy demand due to their greater efficiency and also to a decrease in CO2.

The 72 TWh of additional demand from EVs in 2023 was enough to displace over 260,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day, had it been burned in ICE vehicles. This is comparable to Australia’s total gasoline consumption in 2021. The 100 TWh of additional demand coming from the new heat pump sales in 2023 would have required around 300 TWh of gas, if burned in a conventional boiler to produce the same amount of heat. This is similar to the total gas consumption of France. As the world continues to electrify, the efficiency gains will mean that less overall energy is needed, even as demand for electricity increases.

If that was all that was happening, we could bank it alongside a reduction in fossil fuel use. However, 28% of electricity demand growth was from air conditioning and data centres. That net new energy demand has contributed to a result in which fossil fuel use continued to grow last year.

Finally, the following chart from Ember shows the massive off-take in solar energy that occurred in 2023, more than half of which was driven by China. Capacity additions were 76% higher in 2023 than in 2022, which was itself a record year. Interestingly, solar generation was below expectations because much of the new installed capacity has occurred in countries with less sunlight.

Those countries with the most to gain from solar capacity are lagging. For some, the reason is ideological and policy-driven, in others the lack of climate financing, technology transfer and other de-risking mechanisms are curtailing potential for development. Africa, for instance, has one-fifth of the global population and has huge solar potential but is attracting just 3% of global energy investment, according to Ember’s review. Meantime China is producing an oversupply of modules that is likely to continue into 2024,

“China’s need to find new export markets is a tremendous opportunity for countries around the world to take advantage of how cost competitive and available solar is compared to other generation sources.” (p.36)

That combination of factors means that the biggest potential efficiency gain from installing solar capacity would be if OECD countries contributed more climate financing toward installations in the developing world. This would also have the benefit of contributing to sustainable development and reducing global inequity, both of which are critical to achieving climate targets. A focus on demand-side policies to reduce energy demand in the OECD would enable a faster, more efficient and equitable transition.

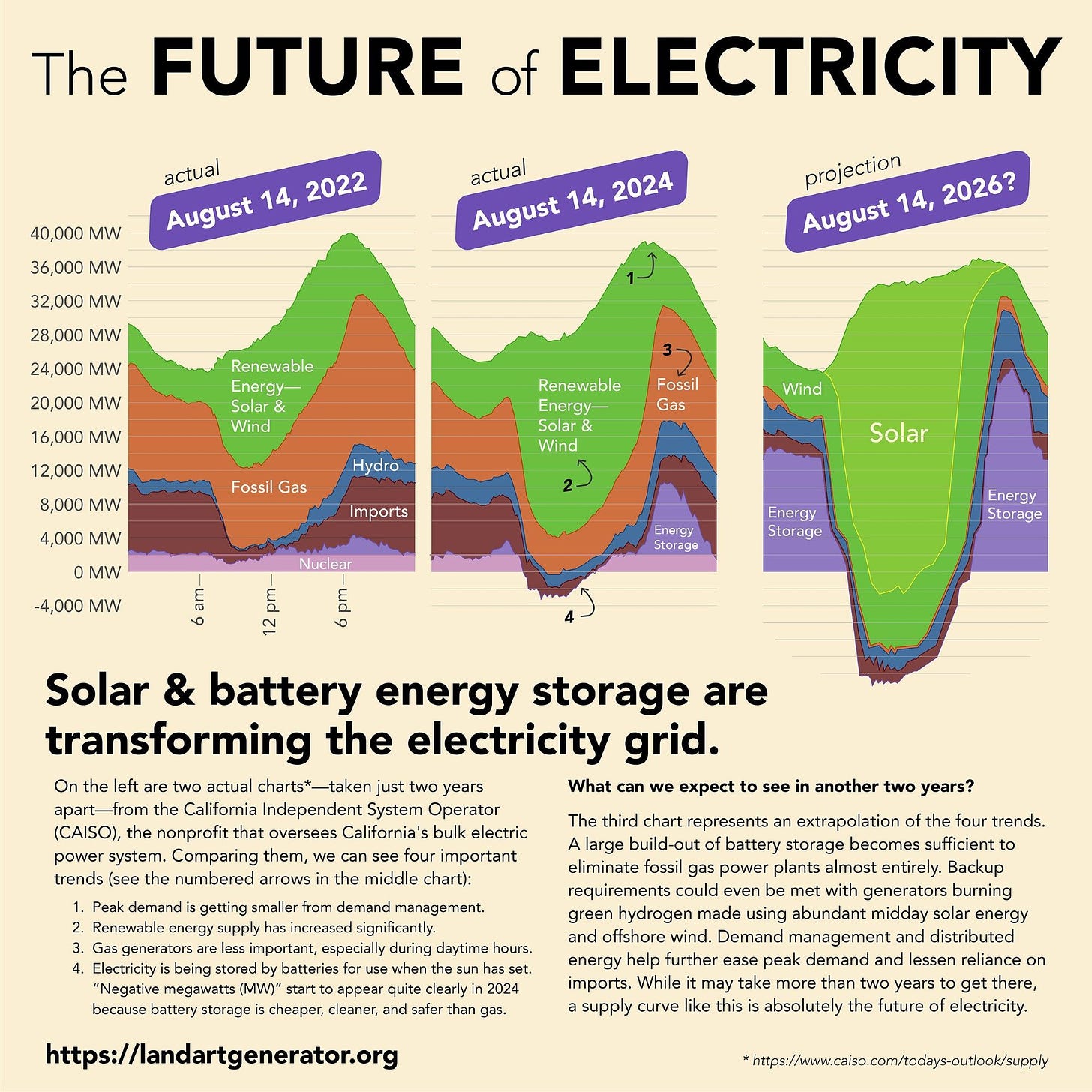

Some headwinds include grid congestion, which is creating major bottlenecks, with a lack of suitable connection points for solar (requiring investment in new transmission capacity), and curtailment is expected to increase in China and California due to insufficient storage. The latter might put at risk the below projection from NGO Land Art Generator, which creates a very visual picture of the potential shape of future electricity generation in California.

Ka kite ano

Bernard and Cathrine

Share this post