Q&A: Who is to blame for the housing crisis?

The RBNZ? The banks? Landlords? First home buyers? Councils? The RMA? Labour? National? Building materials makers? Builders? Real estate agents? Landbankers? Noone in particular. Just voters generally

TLDR: Labour and National politicians, the big four banks and first home buyers should stop blaming the Reserve Bank for the latest housing boom caused by our chronic undersupply problem. Governor Adrian Orr is just following the law and using the tools he has to stimulate.

Both sides of politics, voting property-owning -taxpayers and ratepayers, and the banks, need to look in the mirror, accept their own shares of the blame over the last 30 years for chronic under-building, under-investing and under-taxing, rewrite those rules, and create new tools to solve a very, very big problem. I suggest a 0.5% land tax to pay for housing and climate infrastructure.

Who can we blame for the latest jump in house prices?

The most obvious culprit seems to be the Reserve Bank, which cut the official cash rate to 0.25% from 1.0% on March 16 and then launched a plan to create up to $128b of fresh money over the next three years and use it to buy Government bonds and to lend at near-zero interest rates to banks.

The central bank’s aim was to lower interest rates generally in order to stimulate activity and meet its legislated inflation and employment goals. It knew the main effect would be extra lending into the housing market and a fresh boom in house prices. In effect, that was the aim, because it made more than half of the population feel a lot richer, including a lot of small businesses. The hope was that some would spend that equity and many would keep spending all their incomes. A new housing boom was the feature, not the bug.

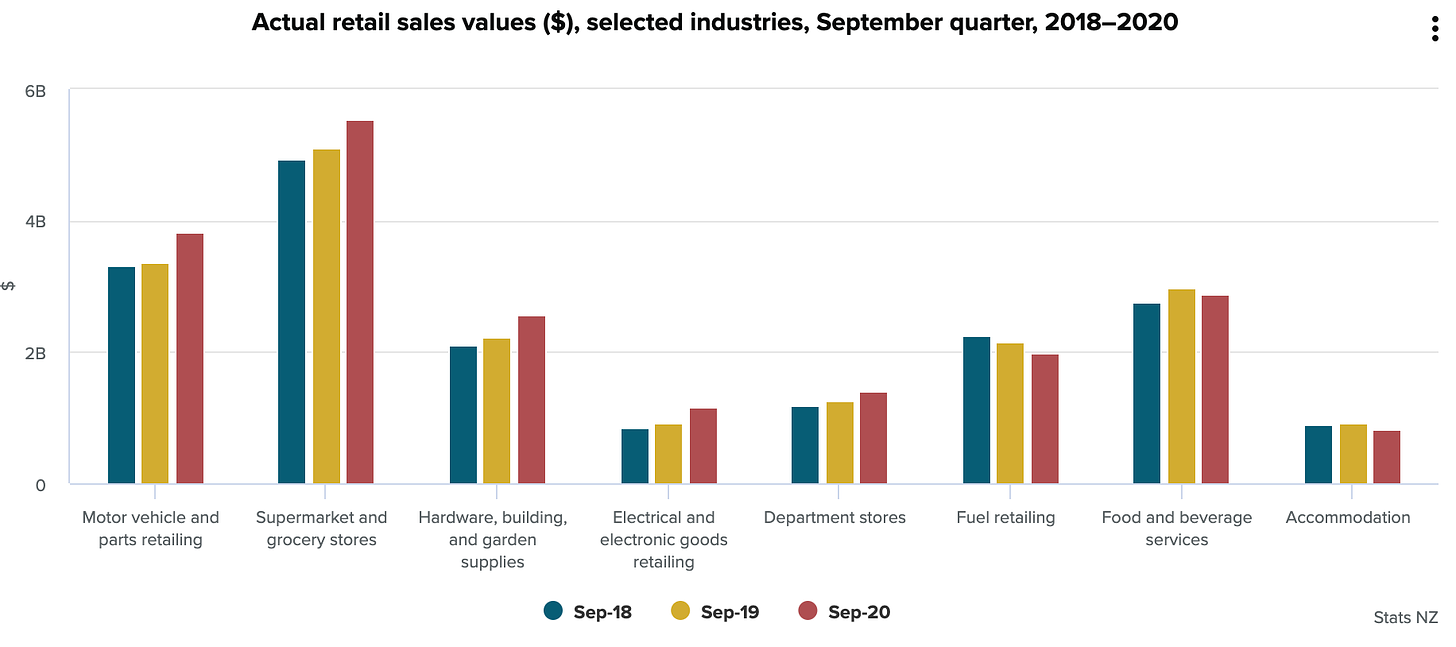

This is not the bank’s fault, and it could be argued the plan worked perfectly. Spending, employment, wages and general economic activity have held up much, much better than expected. The Government’s $14b of wage subsidies and New Zealand’s exceptional performance in suppressing Covid 19 has helped, but the ‘Harvey Norman boom’ has been a big factor. Home owners tired of sitting on their crumby and tattered couches and looking at small, old televisions while in lockdown have raced into Harvey Norman, Noel Leeming and the rest to stock up on consumer durables. Consumers who feel richer and are not spending $11b this year on overseas travel are out there spending heavily.

This is how the New Zealand economy works, increasingly. It is a housing market with bits tacked. The Reserve Bank knew this and acted very fast to cushion the blow. Cutting interest rates was the broadest, bluntest tool it could use, and it worked for the 60% of the population who own homes, and their children, who are more able to access that inflated equity to buy their own homes.

But what about the widening inequality and that renters miss out?

Rightly, the Reserve Bank has said it doesn’t make social policy. That is the Government’s issue. The Government has held back from taking the key investments to deal with this issue. It could loosen fiscal policy a lot more by increasing benefits more for the poorest, as recommended by its own Welfare Advisory Group, but has said it can’t afford to.

The Government could also do a lot more to solve the core problem of a lack of housing supply. It has promised to build 2,000 new state houses each year for the next four years, but that won’t scratch the surface of the 100,000 houses shortage, particularly once population growth from migration resumes in earnest after the borders reopen.

But we don’t have enough builders or migrant workers?

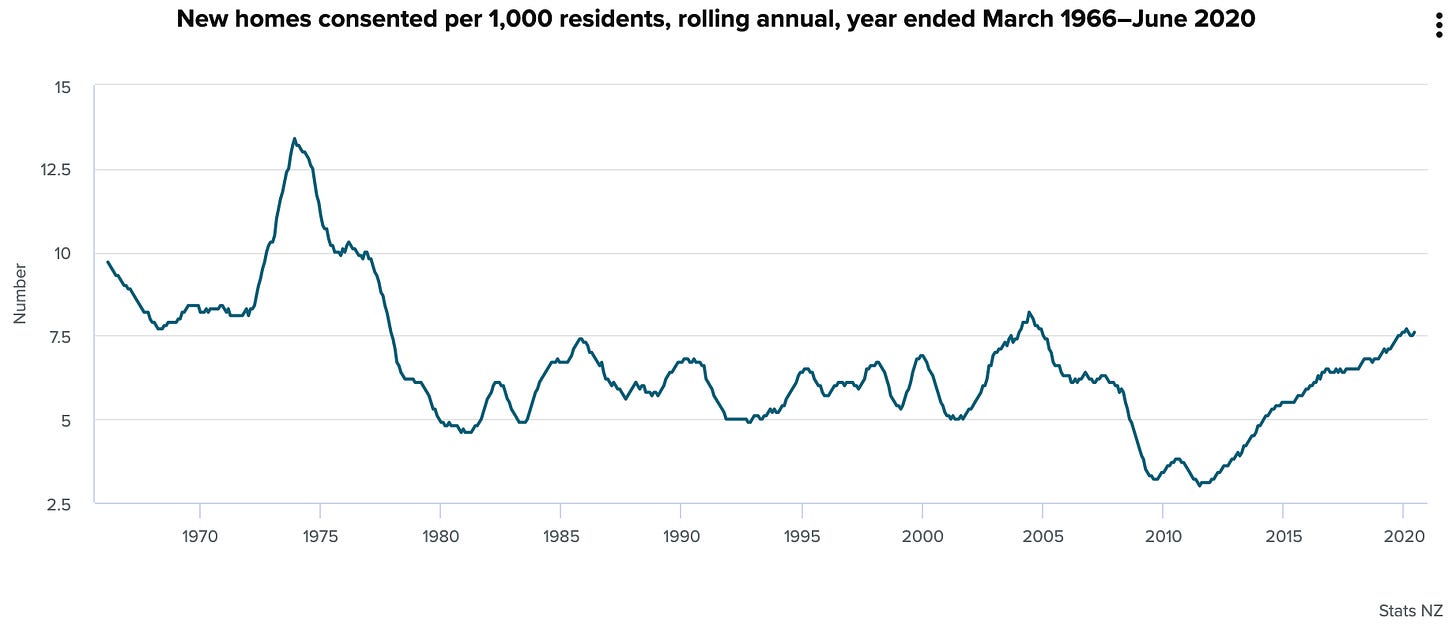

Many say the Government and the industry are building as fast as they possibly can. That’s just not true, particularly if the problem was looked at through a longer-term lens. We are still building at a rate below that achieved in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. The house building industry is mostly made up of small firms building bespoke mega-mansions on sections in suburbs on the edge of cities, mostly for retiring home owners with plenty of equity. They use contractors and don’t over-commit to employing staff or buying machinery because the industry is notorious for booms and busts, often because of changes of Government or Council policies.

The industry has been crying out for years for a guaranteed and high baseline of housing demand so they can confidently employ and train a workforce using expensive equipment and pre-fabrication. The only entity with a big enough balance sheet to do that is the Government. It needs to guarantee more like 10,000 houses a year for 10 years and ensure most of those are small, medium density and affordable, either as state houses or for rent-to-buy or leasehold on Government land.

But won’t removing the RMA solve the problem?

It’s true that the Government now has the numbers and a plan to replace the RMA with a Natural and Built Environments Act (NBEA) and a Strategic Planning Act (SPA) that would make it much harder for NIMBYs and Councils who don’t want to invest in infrastructure to block projects.

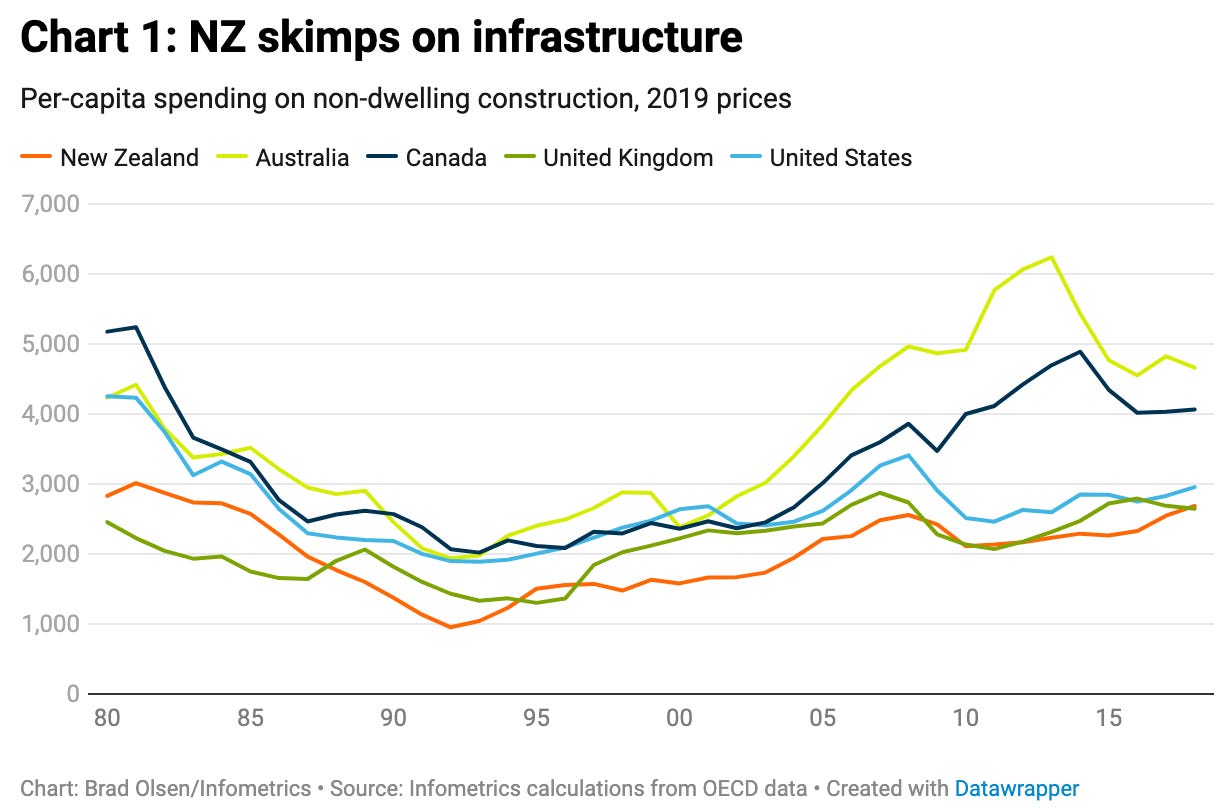

But changing replacing the RMA won’t solve the problem of blockages on its own. Councils often use the RMA to stop having to build expensive public transport, roads and pipes to the edge of town because their own ratepayers don’t want the debt and higher rates that go with it. Those same voting ratepayers are also not keen on the medium density, more affordable housing that is needed. And, just quietly, they know the value of their main financial asset goes up tax free when we have very fast population growth and hardly any extra housing supply growth.

Councils need a lot more central Government financing help to enable this development, and currently the Government wants Councils to pay, or only those home buyers and developers building and buying at the edge of town. Lumping all those costs on that marginal new home just lifts prices right across the board.

Aren’t the banks and landlords and first home buyers to blame?

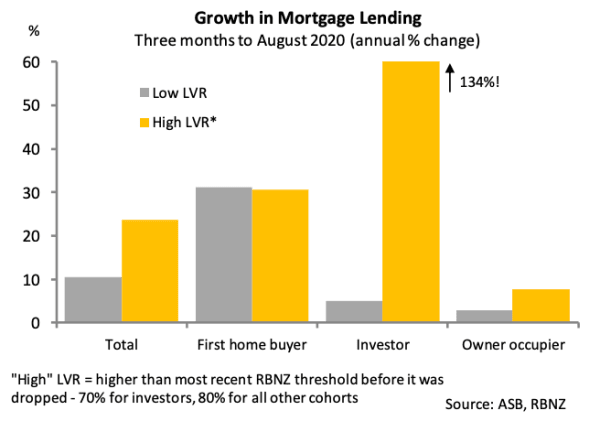

Yes, but they’re only responding to the incentives in front of them. Banks have worked out the Basel capital rules that allow them to apply only small amounts of capital to mortgages mean it is much more profitable, lower risk and easier to grow mortgage lending against existing homes, than to businesses or housing developers.

Landlords have worked out buying existing houses with their existing pumped up equity and cheap bank loans is a sure thing when the Reserve Bank and Government have decided this market is too big to fail.

First home buyers are also responding, and often rightly panicking, at the prospects of missing out. They’re encouraged by politicians making it easier to withdraw from KiwiSaver to build up deposits.

So who’s fault is it?

Ratepayers who vote in council elections and property owners who vote in general elections have repeatedly voted over the last 30 years for policies that restrict housing supply, enable very fast population growth and load the extra cost of new infrastructure onto new home builders. Most renters don’t vote in local elections and more than 500,000 mostly young renters don’t vote in general elections.

A rational and sustainable response would be for today’s property owners and ratepayers to sacrifice just a bit of their untaxed capital gains to pay for the infrastructure and housing needed to ensure today’s renters have a chance to get into the market, and that their kids don’t have to rely on the Bank of Mum and Dad.

They would have to vote for a wealth tax, for Government investment in local infrastructure and for council and government policies that make it easier to build 100,000 new affordable, small, medium density houses in the next 10 years.

My view is the simplest, fairest and fastest way to do this would be apply a 0.5% tax on the value of land worth more than $50,000/ha. It is a broad-based, low rate tax that is rightly progressive, impossible to avoid, fair and could be cordoned off to build the infrastructure needed for affordable housing and climate change adaptation.

You could call it an infrastructure levy that helps redress the inequality, helps pay for new infrastructure and is useful to everyone.

In 1999 housing was removed from the inflation figure. The reserve bank mechanism to slow inflation was to increase interest rates.

Artificially controlled Low interest rates are being used to stimulate demand without controlling housing inflation.

Everyone wants a new house. Put the rates up and watch the demand fall!

Based on the latest inflow of population into NZ the house price rises appear predictable. The following Reserve Bank report models house price rises associated with population increases. The reports modelling remains valid in my view. Not sure if you have seen this report Bernard. But essentially it predicts an 8% house price rise for every 1% of NZ population increase. So if we take the Salvation Army population inflow numbers for the year to June 2020 then we haven't finished with house price rises yet...... Cheers https://www.interest.co.nz/sites/default/files/RBNZ%20migration%20and%20housing.pdf