TL;DR: A screed of bank results in the coming week are expected to show yet more surges in net profit from the big four that dominate our economy and fuel our housing market.

This week the Reserve Bank compiled and unveiled evidence our banks are too profitable, relative to the risk they take for shareholders, but it is leaving any decisions about an anti-monopoly investigation in the hands of the Government.

The differences in risk-adjusted profitability may reflect a lack of competition. RBNZ

Paying subscribers were able to see more detail and analysis on bank profitability below the paywall fold and in the podcast above on Friday. I have now removed the paywall so it can be read more widely after paying subscribers asked for me to open it up. I appreciate the support of paying subscribers, which allows me to do journalism in the public interest such as this.

Much higher profitability with much lower risk

Very high profits can be justified when a company has some sort of secret sauce or special advantage it created and can’t be replicated easily by others. Profits showing double-digit returns on equity can also be justified if they are rare and linked to some sort of extraordinary event or piece of luck whereby a risk taken by shareholders pays off spectacularly.

The rule of thumb is that the higher the risk taken and the higher the volatility of a company’s profits, then the higher the profit will be occasionally and the higher it will be on average. That’s why the idea of risk-adjusted returns is drummed into investors and fund managers. If you want high returns, you have to hold tight for a long time to ride through the big ups and downs as big profits are followed by big losses or vice-versa, in rapid succession.

That high-risk strategy is expected to pay off in the long-run as you hold on as an investor through the highs and lows to get a higher return on average than lower volatility companies that are more like utilities and don’t have many secret sauces.

So are very high bank profits justified then? The RBNZ suggests not.

Government politicians and voters –borrowers and savers alike –have been asking this year whether our big four Australian-owned banks are too profitable, given the record-high profits they’re reporting again this week and next for the half year to the end of March. Those higher profits are in part due to the Reserve Bank’s interest rate hikes over the last year and the $19 billion of special low-interest long-term loans that The Reserve Bank (Te Pūtea Matua) lent the banks in 2021 and 2022.

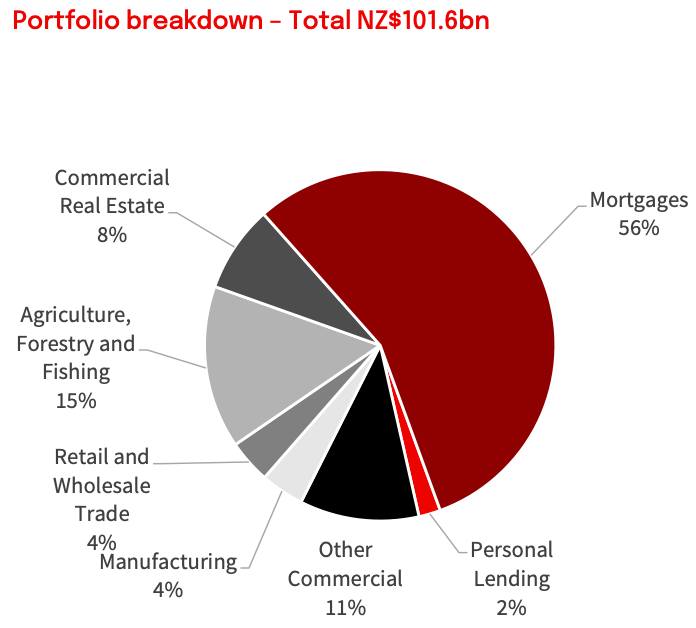

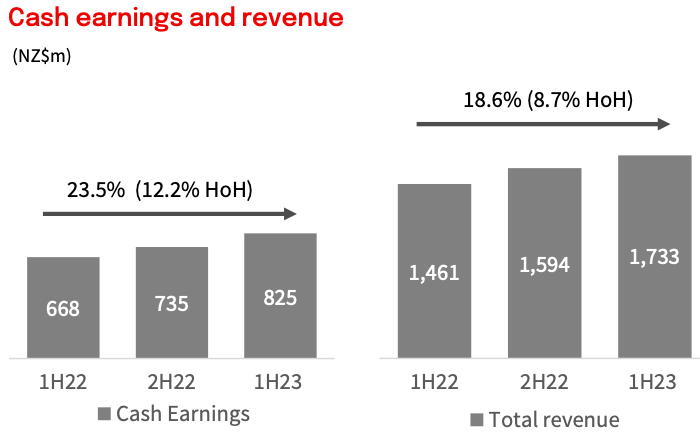

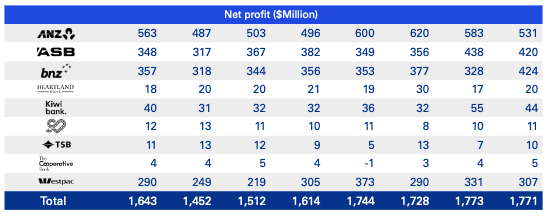

For example, National Australia Bank’s BNZ reported yesterday its first half cash profit rose 23.5% or $157 million from the first half a year earlier to $8025 $825 million. That was driven by a $300 million or 25.8% rise in net interest income due to a 3.5% rise in mortgage lending, and a 41 basis point improvement in its net interest margin to 2.45%. ANZ is due to release its half-year results later today and Westpac’s results are due on Monday. Commonwealth Bank of Australia, which owns ASB, has a June 30 balance date and reported its first half results in mid-February.

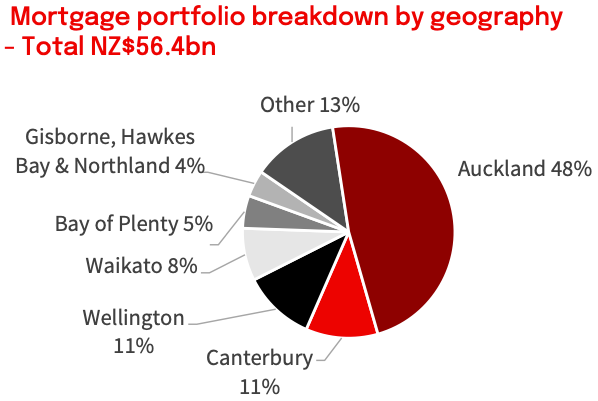

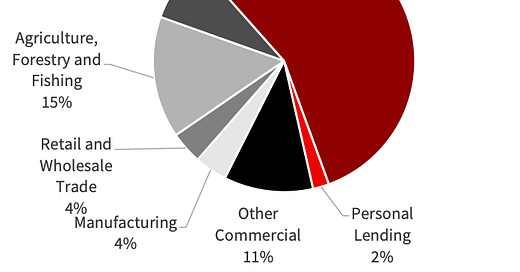

BNZ’s results show how well it is doing from a heavy concentration of lending ever-more against residential land values in our biggest cities, and how rising interest rates and cheap Reserve Bank loans have helped profits.

A housing market with banks latched on

The fruits of our housing market are showing through in ever-growing volume of bank profits, partly driven by an increase in lending as the housing market continues to form the basis of the economy1, and partly an increase in the profitability of taking in deposits, adding a margin, and lending them out again.

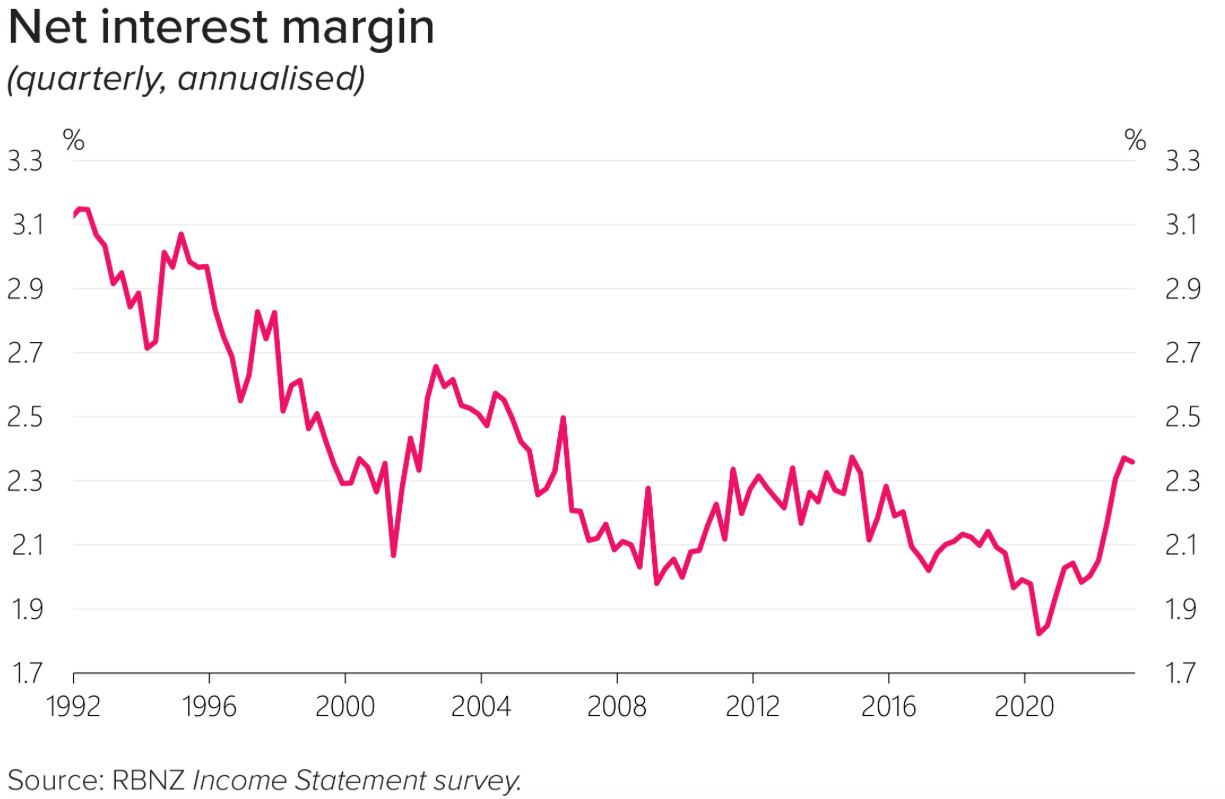

That margin, known as the net interest margin, typically rises whenever central banks increase interest rates because banks pass on rate hikes to borrowers faster than to depositors. The Reserve Bank even complained in late March the banks were not passing on higher deposit rates fast enough, although the central bank itself can claim some credit for the strong profits because it has given them cheap loans and pays them interest on their cash settlement accounts at the Reserve Bank. The biggest banks are also continually bearing down on costs by removing branches and going digital.

New Zealand's banks got an extra tailwind after Covid by a surge in new mortgage lending after the Reserve Bank slashed the Official Cash Rate to almost zero and it removed Loan to Value Ratio restrictions for over a year in 2020 and 2021. That tailwind got an extra 'turbo' boost when the Reserve Bank decided to lend to banks at the cheaper official cash rate for three years. That Funding for Lending programme has closed now, but banks filled up on $19 billion in cheap loans before the end of last year. Also, the Reserve Bank is paying banks 5.25% on the $49.3 billion they have parked in cash settlement accounts with the central bank, largely due to the extra money created during Covid by the Reserve Bank using ‘Quantitative Easing’ to buy Government bonds out of thin air.

BNZ gave this explanation yesterday for its record-high profit:

This increase was due to higher earnings on deposits and capital driven by the

rising interest rate environment, partially offset by housing lending competitive pressures and increased funding costs driven by deposit mix. BNZ results commentary in NAB profit result presentation (page 42).

It’s not just one bank

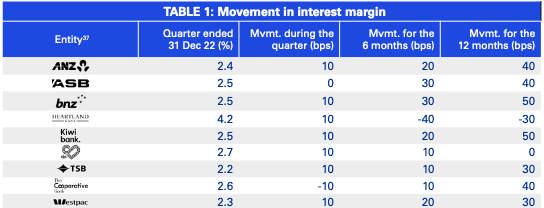

The dark blue bank isn’t the only one making record-high profits. KPMG’s quarterly Financial Institutions Performance Survey (FIPS) report recently collated the collected results until the end of December, including higher net interest margin figures and lower cost-to-income ratios for the light blue (ANZ), yellow (ASB) and red (Westpac) banks.

But is this normal? Out of line with other banks? And other companies?

The banks have defended their higher (and high) profits by saying their profitability ratios have not risen that much over the last 20 years or so and are in line with the profitability of other big companies on the New Zealand stock market. Those statements can be true, depending on which comparisons and which time periods are used.

Some of the higher-volatility stocks on the NZX with smaller balance sheets and revenues do have double-digit returns on equity, but they are also seen as riskier because of that volatility and relative size. The big four banks’ profits are consistently large and the returns on equity are consistently in the mid-to-low teens in percentage terms. That indicates their high profitability is not matched by the same high volatility and risk that other NZX companies with similar double-digit returns exhibit.

For example, the entire NZX’s profit on equity last year was around 5%, while listed financial stocks also returned 5%. NAB didn’t break out BNZ’s return on equity figures in its presentation (page 6), but the group’s ROE was 13.7% in the first half. For example, New Zealand’s retail listed companies have returns on equity of about 12%, but are also much more volatile.

So the Reserve Bank took a look at the risk-reward relationship

This question of how much profit is too much is tricky, but the Reserve Bank took a much closer look in its Financial Stability Report this week with a special topic report on ‘Trends in Bank Profitability’. It should be required reading for every bank customer, voter and politician. The Reserve Bank doesn’t come out and say the banks are making too much profit, but the detail in its analysis is stark and shows they are the most profitable in the world with relatively low volatility or risk. I asked about this issue at the FSR news conference and the exchanges are in the podcast above.

Deputy Governor Christian Hawkesby and Governor Adrian Orr described the banks as very profitable and said they should use those profits to remain strong, to help out customers in trouble and to invest in their systems to improve resilience and service levels. Hawkesby and Orr stopped short of saying the banks were ‘gouging’ the public, but their analysis backed up former PM Jacinda Ardern’s warnings too banks in November last year that their consistently high profits were ‘wrong’ and put their ‘social licenses’ at risk.

The analysis showed a rebound in net interest margins to pre-GFC levels because of the lagged effect of term deposit rates rising slower than mortgage rates.

The Reserve Bank signalled it expected the net interest margin growth to be temporary, but also noted profitability levels had quickly bounced back to pre-Covid levels. The average bank return on equity in the 14 years since the GFC has been 12.4%, with the range for the average quarterly ROE moving between 7.3% in June 2020 to 16% in December 2011. Here’s the bank’s comments in the FSR (bolding mine):

Profitability ratios, such as the return on assets and return on equity, are more robust indicators of performance. Banks’ balance sheets have continued to grow since 2020, reflecting growth in the economy . Their equity bases have been further supported by lower dividend payout ratios, as banks have started to increase capital in anticipation of the higher future capital requirements. As a result, the return on assets and return on equity are at similar levels to those in the decade prior to the pandemic. Reserve Bank analysis

Here’s the killer chart that decides the issue

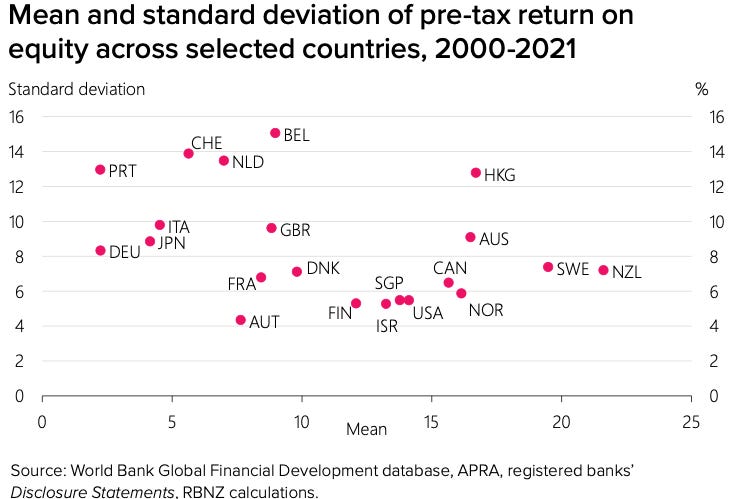

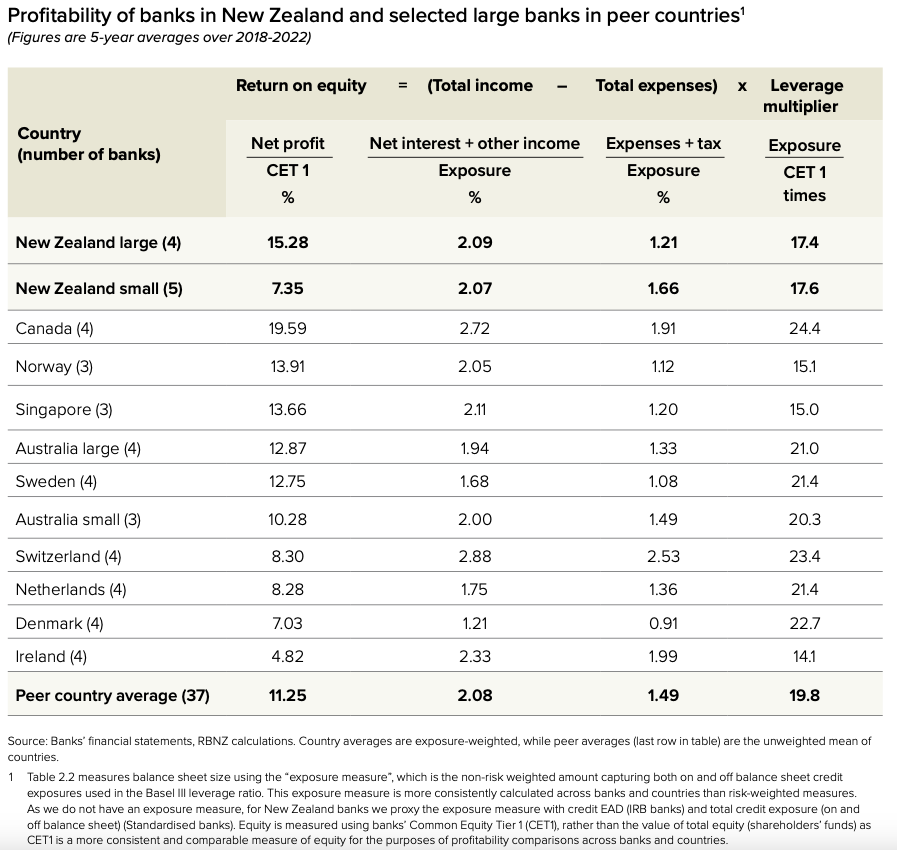

There are ways of trying to measure profitability vs volatility and risk to discover the risk-adjusted reward is worth it. The Reserve Bank produced this chart and table below showing New Zealand’s banks had the highest returns on equity in the world over the last 20 years, but were also near the bottom of the pack for volatility of earnings. That means their profitability was much higher relative to the risk for shareholders. That’s a classic sign that profitability is too high.

Here’s the Reserve Bank’s very careful reading of this apparent smoking gun chart (bolding mine):

While the banking sector as a whole does not appear to be materially more profitable in 2023 compared to the past 30 years, the large New Zealand banks have been more profitable than the rest of the New Zealand banking sector and large banks in a number of comparable economies in recent years.

Higher risk associated with operating a bank in New Zealand relative to other countries is a potential driver of high profitability for New Zealand banks. However, the volatility of earnings, a standard measure of risk, has been relatively low in New Zealand compared to other countries in recent decades. This suggests that risk does not fully explain the relatively higher returns of New Zealand banks, although it should be noted that this has been a period of ongoing economic growth and strong housing market performance.

The differences in risk-adjusted profitability may reflect a lack of competition. RBNZ in FSR

Here’s another view of this in table form, including other measures of riskiness showing New Zealand banks being lower risk, but much more profitable than peers overseas:

‘It could be a lack of competition. Or some other things’

The central bank and bank regulator (but not competition regulator) then went on to muse about the potential reasons for the anomaly of risk-adjusted returns, other than a lack of competition, including:

the banks’ large scale giving them economies of scale not available to peers overseas and New Zealand;

the banks being subsidiaries of Australian groups meant head office costs weren’t as high here, relative to domestic competitors or peers overseas;

that the banks’ Australian shareholders may demand higher return on equity because dividends from New Zealand banks are not ‘franked’ or tax-free for Australian shareholders; and,

the big four here have very simple banking structures without the riskier add-ons of investment banking and funds management that global peers have.

‘We analyse. You decide’

The Reserve Bank made no further comment, other than to say the banks should use their high profitability to maintain their social license and help customers.

The benefits of profitable banks are particularly evident in the current environment, with New Zealand banks in strong positions to manage increasing stress in their lending books and a deterioration in global economic conditions.

Importantly, profitability allows banks to support their customers by taking a long-term view in times of stress. It also enables the necessary investment in systems to improve efficiency and operational resilience.

Therefore, profitability puts banks in a position to earn their social licence by contributing to a sound, efficient, inclusive, and dynamic financial system. RBNZ in FSR

Time for a market study then?

Reserve Bank Chief Economist Paul Conway has previously said he agrees with calls for the banks to be the next topic for a market study by the Commerce Commission. New Commerce Minister Duncan Webb hinted one was being considered in a piece in The Post-$$$ this morning by Rob Stock.

“I’ve seen the bank profits and they’re significant, and certainly that’s factoring into the decisions we are making.”

“The question is where we can get the biggest gains for consumers so we are looking across the entire market, whether that’s in banking, insurance or elsewhere.”

“But certainly banking is one area that we are interested in and when we make a conclusion on that we will make an announcement.” Duncan Webb quoted in The Post-$$$ (Rob Stock.)

‘Nothing to see here. Move along’

BNZ CEO Dan Huggins was quoted as saying a market study was not necessary and that the banking sector’s ROE range of 10-14% was appropriate relative to global peers and NZX companies. He said the public would be pleased New Zealand had a strong banking sector in the wake of bank failures overseas in recent months.

“I don’t think that (a market study) is necessary. The industry is very, very competitive.

“We certainly want to see a fair return on the money we have invested in the bank.

“There’s $11b invested, and when we look at the return on that, on an industry level, that’s 10% to 14%, and we think that’s an appropriate return when we look at global peers, and when you compare us to others on the NZX.” BNZ CEO Dan Huggins via The Post-$$$ (Rob Stock.)

In my view, I think the Reserve Bank’s analysis shows that our banks are making super-profits relative to the risks they take on for shareholders and a market study should be done.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

PS: Want this opened up?

IE we have a housing market with bits tacked on, not a real economy.

Share this post