How the ladder was pulled up

And why the post-1984 generation that did it accidentally on purpose can't find a way to either climb back down, or lower the ladder to the generations born after 1984.

TLDR: A generation of voters in the 1980s and 1990s accidentally on purpose engineered a monstrous transfer of wealth to themselves and pushed huge costs on to future generations. They climbed to great riches on the backs of their parents and then pulled up the ladder for today’s young. Now these mostly older voters don’t know how to (or don’t want to) drop it back down again for those graduating into a hellscape of impossible housing affordability and massive climate change costs.

(This was first published on Stuff on Dec 5 last year, but it’s worth sending out to The Kaka’s subscribers, given events of recent weeks and ahead of this coming Monday’s announcement of new carbon budgets by the Climate Change Commission. I’ve updated throughout with latest detail.)

There seemed to be lots of good news in late November on the housing and climate fronts for the coming generations to digest.

New housing consents hit a 46-year record high in the year to October, Jacinda Ardern told us in Parliament’s debating chamber, in answer to question about the housing crisis from Opposition Leader Judith Collins.

Then the Prime Minister, elected in 2017 with the promise of addressing her generation’s ‘nuclear-free moment,’ stood up again in the same chamber less than an hour later to declare a climate emergency and pledge to make the Government itself carbon neutral within five years.

“This declaration is an acknowledgment of the next generation: an acknowledgment of the burden that they will carry if we do not get this right and if we do not take action now,” Ardern said.

“We cannot underestimate a generation that is full of anxiety over the reality of climate change for them and their generation. And it is up to us to make sure that we demonstrate there is a pathway, there is a plan for action, and there is a reason for hope,” she said.

“It is about the country they will inherit and it's about the burden of debt they will inherit unless we make sure that we demonstrate leadership on this issue.”

Those fine words seemed to be addressing the concerns of the generations born in the last 30-40 years. The pledge to make Government carbon neutral in five years was certainly cheered and clapped by both the younger and older spectators in the public gallery.

Job done then? No. Nowhere near it. Actually, the prospects for a ‘just transition’ to carbon zero by 2050 are so infinitessimally small as to be not be there at all. That’s because the intergenerational wealth transfer that happened over the last 30 years so dominates our political and economic landscape that the savviest and most pragmatic politicians know it cannot be turned around. They just hope the young haven’t worked it out, don’t notice, and don’t try to really shift the political centre of gravity.

The ladder was pulled up and it’s staying

Why so hopeless? The proof is at the polling booth and in every statistic and news report we see every day. New Zealand just voted again to maintain the status quo by an overwhelming margin and just suffered another housing affordability ‘shock’ that entrenched that wealth shift in concrete. Those succeeding generations of voters who accidentally on purpose pulled up the ladder on New Zealanders born after 1984 are now stuck. Even if they wanted to either climb back down themselves or let the ladder down for the young, especially if progeny of renters, they either won’t or don’t know to do it without torching the ladder and the whole treehouse.

For example, let’s take a closer look at the Prime Minister’s words on that Wednesday in November, and then contrast the experiences of today’s 18-39 year olds with those generations voting through the 1980s and 1990s.

One way to peel away the rhetoric from the reality is to look at the ‘record’ high amount of house building going on at the moment. It felt like the PM’s strongest defence to the accusation from the Opposition that the Government wasn’t doing enough to increase housing supply.

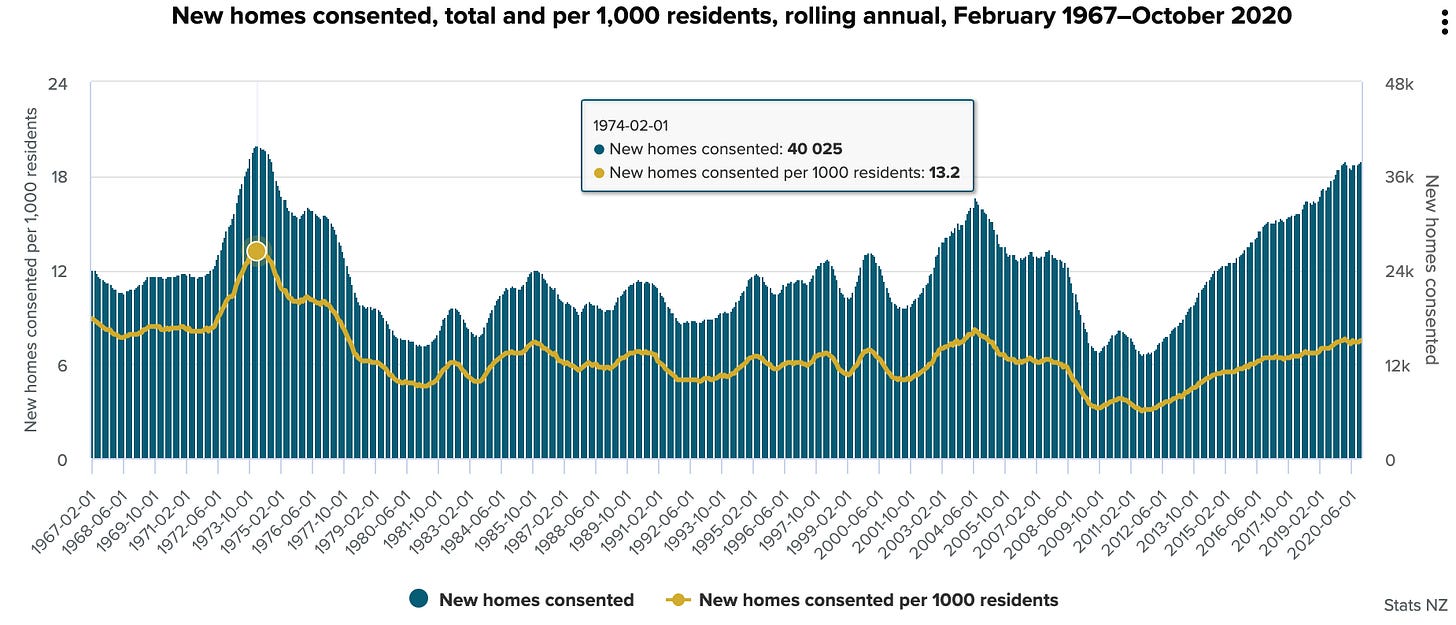

It’s true that the number of building consents issued in the 12 months to the end of October was 37,981, which was the highest in any one year since the year to the end of February 1974. But it doesn’t sound so impressive when you realise that New Zealand’s population in 1974 was 3.03 million and it is now nudging 5.1 million. That mean the number of new homes per thousand people being built back when the first-time voters of the 1990s and 2000s were being born was 13.2. Today’s ‘record’ building rate is just 7.5. The yellow line in this chart shows the building rate.

New Zealand’s house-building rate through the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s averaged around nine, but then dropped to around six per thousand through the late 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and through until the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. It then dropped below four and was below the building rate New Zealand had in the Great Depression and early in World War Two.

All that meant New Zealand had enough homes for a reasonably fast growing population through the post-war years up until the early 1980s. That kept house prices low relative to incomes at around two to three times income. Also, people buying houses in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s were able to borrow at an interest rate of around three percent from the Government’s State Advances Corporation.

They were also able to capitalise their family benefits into a deposit. The family benefit was a universal payment per child set at about a quarter of the unemployment benefit, which would be about $60 a week in today’s benefit levels. Back in 1978, a family with three children could magick up a deposit by capitalising their family benefit from the Government of around $2,000 to buy a new house, which cost about $20,000 and were readily available in new suburbs on the fringes of town. The Government would then lend you the rest for a house costing around three times the average annual wage of $6,300.

That affordability was partly because the Government and councils saw it as their role to enable development of suburbs by paying for infrastructure such as roads or pipes and electricity. They did that by taxing all taxpayers (mostly) with relatively high income tax rates. The Government had a department called the Ministry of Works (MoW) that paid for and built all these things. It meant the cost of new development and infrastructure for new families and children were smeared across the whole population and paid for with taxes that were quite high. A generation of leaders and taxpayers through the late 1940s, 1950s, 1960s and 1970s saw it as their role to ‘pay it forward’ by subsidising the cost of housing and new infrastructure. The social contract was about building for the future and paying for the future now.

Then the generations of voters and taxpayers after 1984 decided to change that social contract. They thought and voted and changed the laws in a way that meant they ‘pulled it back’, rather than ‘paid it forward.’ They argued (and still do) that it wasn’t fair on them to ‘overpay’ for tomorrow’s infrastructure with high taxes. They viewed that spending by ‘Uncle MOW’ as wasteful, too controlling and environmentally damaging (Think Big’) at a time when the population had stopped growing fast and was likely to be stable and become more aged over the next 50 years.

They argued: ‘Why should we pay with high tax rates for ‘other’ people’s children, people who weren’t even born yet, or people who hadn’t migrated to New Zealand yet (or wouldn’t because they believed the great migrations of the 1950s and 1960s were over).’ They wanted the freedom to spend their earnings however they saw fit and were taught to distrust ‘big’ Government as the cause of their problems, not the solution.

The rash of lawmaking and big structural changes to the economy and government between 1984 and 1993 included the State Sector, Public Finance and Fiscal Responsibility Acts (which entrenched the low Government debt and low Government investment ethos we have today), the Reserve Bank Act (which prioritised low inflation over all else) the Resource Management Act (which made it much easier to block big and little developments by anyone), Local Government reforms to entrench user-pays, and low-rate and broad-based tax reforms for wage income and spending, but not capital or assets.

The big tax incentive

One of the most important changes was little noticed at the time, but has had a huge impact over time. Before 1989 there used to be a tax break for putting money into private pension funds. Given there was no such tax break for capital gains on property and business assets, it was deemed an unfair advantage for pension funds and removed with the aim of creating a ‘level playing field’. New Zealand is now almost completely on its own now in the western world as not providing any tax breaks or incentives for saving into managed or pension funds, which go on to invest in companies, bonds and other financial assets, and not taxing capital gains or wealth.

Now tax rates on income and wealth are relatively lower and non-existent respectively, and the cost of new development at the fringes is loaded up onto those who pay for new houses. These are development contributions for new buildings to pay for pipes and roads, and GST on building materials. Consumption and wage income are taxed broadly, but wealth, land and interest costs on property are not taxed at all. All this meant the marginal cost of a new home spiralled up, the subsidies for new homes paid for by taxpayers at large dried up, and both public and private investment in infrastructure and capital became much smaller than other developed countries. That generation of voters made a deliberate decision over three decades to lower taxes, lower investment and load up new costs on future generations. They underinvested in the future and chose to consume now rather than ‘pay it forward’.

The creation of vast wealth for home owners wasn’t deliberate, but now it’s happened, it is politically and financially impossible for that ‘pulled it back’ generation to give it up. It happened ‘accidentally on purpose’, but its retention is anything but an accident. It’s worth looking at the scale to give a sense of why it’s politically so hard to impose a wealth tax or for any winning politician to even suggest they might want house prices to fall.

The value of New Zealand’s housing stock rose from $25b in 1978 to $1.46 trillion by November, as measured by Homes.co.nz in late November. Housing debt has risen from around $5b in 1978 to $293b in October this year, which means this generation of home-owners now have homes that have a net worth of $1.2 trillion or seven times their disposable household incomes (ie after taxes) in 2019. That compares with homes that had a net worth of just two times their disposable incomes in 1978. That was partly because taxes were higher then, but it’s mostly because of astonishingly high and sustained rates of house price inflation.

This wasn’t deliberate. The ‘pull it back’ generation got extremely lucky, but they made their own luck with the various changes in legislation that created a once-in-a-century collapse in mortgage interest rates from over 15 percent to back to around three percent, a near halving in the building rate and a surprise return of much faster population growth through migration than they expected in the late 1980s and early 1990s when they rewrote the economy’s rules. But now it has happened and they have ‘pulled the wealth forward,’ they can’t bring themselves to ‘give it back or pay it forward’. Changing the habits and financial structures of a lifetime are just too hard.

An addiction we can’t kick

Many small businesses and the personal wealth and retirement plans of most older New Zealand are now completely intertwined with the value of the equity in their houses. Our banking system is now completely reliant on the mortgage market and any suggestion of a price fall makes bankers and the Reserve Bank nervous.

The ‘heat’ or lack of it is now integral to the way voters feel about the health of the economy and their own personal spending plans. It’s no accident that the Reserve Bank chose to inflate the housing market to stimulate the economy this year. It was the only blunt instrument it had. Back in the 1970s banks were more reliant on lending to businesses and farmers than home owners. Now they lend twice as much against houses than they do to farm and business assets combined.

Tax-free capital gains on leveraged equity in homes is not only the national past-time and topic of summer BBQ conversations (for those with backyards and BBQS they own), it has become a bigger earner than real jobs. The value of houses has risen $200b in the last year, which is more than the entire nation’s net disposable income for the year of about $178b. Workers from the Prime Minister down will have ‘made’ more tax-free from their homes than their real jobs.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern understands this in a visceral way, as she demonstrated again and again in the last two years. She said she and and the Labour Party had proposed a Capital Gains Tax at the 2011, 2014 and 2017 elections and had been knocked back every time. Even in the throes of ‘Jacindamania’ in September 2017, she was forced to rule such a tax in her first term. Even in this election, the question on every reporters’ lips at everY turn was: has Labour really (really) ruled out a CGT or wealth or land or stamp duty tax? The PM knows when she is beat. She knew it in April 2019 when she ruled it out for her entire political lifetime at the ripe old age of 39.

The issue of taxing land and property is crucial to this issue of generational wealth transfer and the possibility of a ‘just transition’ to carbon zero by 2050. Paying for the housing and transport infrastructure to adjust for climate change will cost hundreds of billions of dollars. That will have to be paid for with taxes on the wealthiest over the next couple of decades. That will be the battle of our political age.

We’ve seen the early skirmishes and where the political balance lies in the last three years. We saw it in how the respective major parties campaigned in this year’s election. For example, the merest of hints that prices of double-cab utes might go up to pay for more electric vehicles was weaponised by National to appeal to older (hard-working and property owning) suburbanites.

A low level guerilla war of types is being waged at local levels between younger voters on bicycles and commuters in cars scrapping over room for cycleways and rates increases for bike racks. It’s also going on between younger renters wanting high-density apartments vs inner-city villa-dwellers who don’t want anything blocking the sun on their desks. Auckland had its battle in 2016 with the Unitary Plan. It is breaking out again in Christchurch and Wellington now as councils dominated by the leafy suburbanites who vote in local body elections scream back at the orders from Wellington for densification — orders that are not backed with Government funds to underpin these apartments.

Ready to change everything?

That $1.46t of housing wealth is based on land values in suburbs that cannot exist without local roads, motorways and cheap cars. Changing it would require a complete change in where people live, how they get around, the value of their properties, what they live in and how they are taxed. Covid-19 reinforced it by reviving the love for suburbs and back yards and spare bedrooms.

This is not a discussion politicians in the centre want to have. Ardern ruled out wealth taxes. Local and central Government politicians are tiptoeing around the political land mines of congestion charging, big rail investment costs, subsidies for public transport and any idea of massive taxpayer-subsidised apartment building that would pressure rents and prices down. Auckland Council’s decision to cut investment on electric buses and infrastructure for housing growth also showed that. There is nothing scarier for a mayor or councillor than a rates revolt from the leafy inner city suburbs. They know young renters don’t vote in local elections, so they vote for the status quo.

Political landmines galore

The issue of New Zealand’s performance on climate change and even the latest declaration simply highlight how sensitive these fundamental questions are in our political and economic landscapes. The ‘feebate’ scheme was dropped and replaced with a plan to increase emissions standards, which will have the effect of increasing the cost of used cars for poorer commuters in a way that isn’t so easy to characterise as a ‘green tax’. Politicians run a mile here when the ideas of a ban on used imports or a hard ban on petrol and diesel imports by a certain date are raised.

To give an idea of how hard it will be, just look at the Government’s own carbon-neutral plans, and New Zealand’s progress so far on reducing emissions. There are 146 electric cars in the Government’s fleet of 16,000 cars. Just seven days before the Prime Minister’s declaration in late November, her own Police Commissioner announced a five-year commitment to buy 6,000 petrol-powered Skodas to replace its Holden Commodores, starting next year. He cited performance and cost reasons. Ardern’s climate announcement this week added no new money to the pot to make it happen.

Unravelling the last 30 years of wealth transfer and cost pushing to future generations is currently deemed politically impossible. Why? In early December the Electoral Commission revealed the full turnout figures for the election in November. The number of young voters improved, but not enough to make a difference. There were 499,649 potential voters between the age of 18-39 who chose not to enrol, or vote if they did enrol.

Perhaps they are the savviest and most pragmatic of us all. They realise there’s no point in bothering with democracy when it refuses to address, let alone reverse, the biggest wealth transfer in our history.

Best to settle in and pay the rent.

Best. TLDR; Ever.

Seriously though, your columns are an island of sanity in our current political landscape dominated by Polyanna syndrome. In my experience, many of the 0.5 million lost voters are too terrified to even admit that it is even happening. And with violence in the US and Trump to distract us, it is easier to ignore local politics (what ... we can't vote in US elections!!).

I've also read your article "The dirty little secret in this migration debate":

> New Zealand is kidding itself that it is growing its economy and its wealth, but all it is doing is bringing in more people, working them harder for less pay, and refusing to invest in the underlying infrastructure and social fabric of the country because its delivers a short-term financial and political gain. It is disgraceful.

...

> The bigger picture is this is effectively a bi-partisan migration 'policy' that is both delusional and fraudulent.

This "fastest population growth in the developed world" also accidentally on purpose reduces the necessity of investment in young NZers, undermines the market power of young workers while further increasing property values. Our housing crisis seems to be the conclusion of so much fraudulent policy over several decades.

I think it is interesting that the motivation for the open-door approach to high migration is primarily related to successive governments wanting to rapidly attract young workers to migrate to NZ given our ageing population demographic. But the only way either Nat or Lab could bring in 70,000+ new people annually, and house them, was by encouraging NZers to become landlords. So that activity was incentivised both by tax breaks for landlords respecting that as a business it was otherwise normally uneconomic (when house prices were relatively stable) and accommodation supplements for tenants. Successive governments couldn't have got away with bringing in a million extra people into NZ over 20 years without the much-maligned landlords being there to provide rentals to house all the new arrivals. House prices spiralling out of control was just an unintended consequence. If I am right in what I surmise, and about the true albeit unstated, motivation for the policies they have adopted, then Nat and Lab have created a massive social mess (inequality) while trying to fix a looming social problem (an ageing population). That is my guess about 'why' we have got to where we have.