For owners, houses are actually cheap

Treasury and Reserve Bank see prices rising another 22% over next 3-4 years because interest rates are low, housing supply isn't growing fast enough and the tax incentives are still there

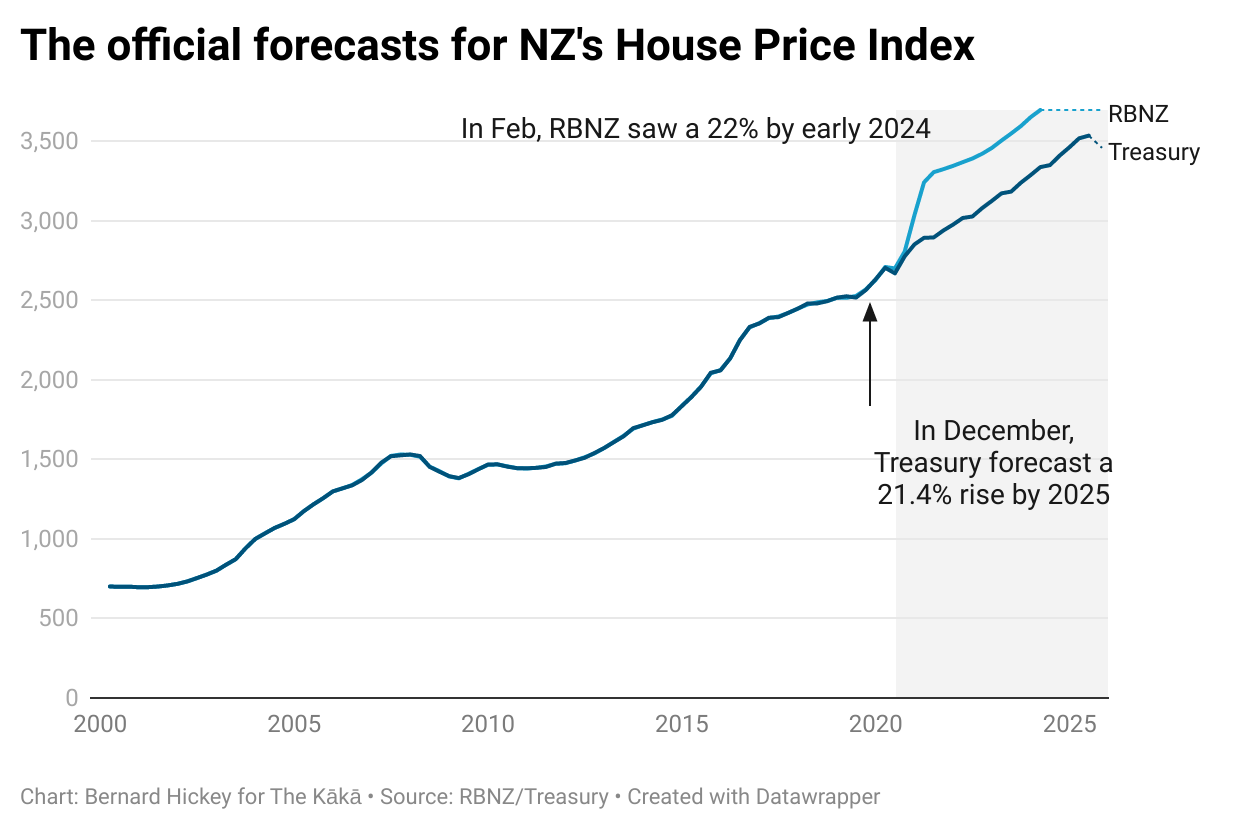

Treasury and Reserve Bank see prices rising another 22% over next 3-4 years because interest rates are low, housing supply isn't growing fast enough and the tax incentives are still there, Bernard Hickey reports, for those wondering how prices could possibly go any higher. Prices would double almost immediately if buyers and banks followed their basic instincts and were not shackled by the Reserve Bank’s lending restrictions.

If you are a first home buyer about to walk into an open home or auction and compete against bidders who already own a home or homes, you’d best look away now. What you’re about to read is probably not good for your peace of mind.

Houses are actually very cheap to buy and own if you have owned a home for a few years, have surfed the equity in their homes higher without having to pay tax, and have a full-time job. Put simply, all the talk about house prices being obscenely high and unable to possibly go any higher is just plain wrong when you look at the actual weight of housing debt and mortgage costs.

When the Prime Minister and Finance Minister say the recent stunning rises in house prices are unsustainable, they are wrong. Not only are they sustainable, but there is plenty of room for another 20-30% rise in prices over the next three to five years, even with the Reserve Bank’s latest controls and the prospects for more. When people walk away from auctions shaking their heads and wondering how anyone could pay that much for a house, they should realise it could actually have been higher.

Here’s a fair example of that sense of disbelief via Twitter from Keith Lynch, a Stuff editor, after he watched a house sell this week: “Auction today: House had 570k RV. Pre-auction bid of 710k accepted. Goes for 925k to a phone bidder. Most of us in the room walked out laughing in disbelief.”

Vincent Heeringa, a former financial journalist, chipped in helpfully: “Run-down house next door on busy street has CV for $1.8m. Sells in 10 days for $2.8m.”

It would be funny if it wasn’t so true. If the auctioneer’s audience had stopped to do some spreadsheet work afterwards, those laughs may be more like howls and moans.

Brace for these facts of life:

The national loan to value ratio is just 20%. New Zealand’s houses are now worth over $1.5t but there is just $300b worth of mortgages against them.

If the nation could borrow 80% of the value of the housing market all at once, it would be able to pump another $900b in debt into the market and still be paying less than 20% of disposabe income in mortgage costs. Most renters pay more than 30% of their disposable income in rent, so that would be no problem.

Home owners are collectively paying just 6.0% of their disposable income in mortgage interest costs, which is down from a high of 14.0% in late 2008. That’s all because of the near-trebling of house values since then and the fall in mortgage rates from over 10% to around 2.5-3.0% now.

Banks currently use a base threshold of around 6.5% as their affordability measure for loans, which means they currently reject a loan application if the home buyer could not afford an interest rate of 6.0%. Currently the Treasury and Reserve Bank are forecasting interest rates to be around 2-3% for another decade.

The banks use that affordability threshold as a filtering tool to keep the quality of their lending high and restrict the amount of capital they have to put aside against each loan. Like most of us, they also used to believe that 6% was more likely to be the long-run average. But if they were to decide that interest rates were more likely to stay closer to 2.5% over the long run, they could lower that affordability threshold. That would unleash massive new lending and house prices.

12% of home buyers in February bought the house with cash. That’s up only slightly on the long-term average and a function of many rental property investors with multiple properties and floating rate ‘draw-down’ mortgages able to buy without getting bank approval by sucking equity out of their other properties at will, especially as that equity is rising.

The awful (or brilliant) truth of the housing market is prices could easily be double or treble their current levels if home owners and banks had been allowed to borrow and buy without restrictions, as was the case before 2013 and (briefly) over the last year.

If the Reserve Bank had not intervened in 2013 to calm things down with loan to value ratio restrictions, average prices would have raced towards $2m in Auckland, over $1.5m in Wellington and over $1m in Christchurch. The unknowable is what prices would be now if the Reserve Bank had succeeded in imposing Debt to Income (DTI) multiple controls in 2017. The Reserve Bank blindsided the-then National Government in 2013 and was unable to get permission to introduce a DTI limit in 2017.

This may seem like crazy talk and is certainly out of step with the ‘feel’ of prices in auction rooms. But like many, I thought prices were at ‘crazy’ never to be repeated levels in 2007/8 and 2012/13. Back then, I thought the ‘natural’ dynamics of demand and supply would ensure some sort of ‘return’ to rationality. After all, I thought, no asset market is guaranteed or invulnerable to falls, as well as rises. There are no free lunches, I thought, and surely supply would rise to match the demand and suppress prices.

There’s always a bailout

But that was before the Global Financial Crisis and the latest Covid-19 crisis proved that central banks and Governments will intervene to prevent financial collapse and to protect the value of assets.

Part of the response was a natural outcrop of independent central banks targeting inflation, and inflation seeming to be ‘unnaturally’ and stubbornly low for a decade. A closer look at the widening spread of globalisation of both manufacturing services, along with a weakening of the power of workers in setting wages, has seen inflation be much weaker than everyone expected. That mean central banks cut interest rates to zero and then started buying bonds with freshly invented money to get long term interest rates down.

Since 2008, the world’s central banks have invented more than US$20t to force down long term interest rates. That’s equivalent to a full year’s GDP of the world’s largest economy. Our own central bank joined the club last year with a plan to buy $100b or about 30% of our GDP.

Part of the response was central banks and regulators, rightly, intervening to prevent the sorts of financial collapses that triggered the great depressions of the late 1800s and 1929/30. No one would begrudge a central banker that stopped a cascading collapse of banks for no good reason other than a lack of liquidity.

But the pattern is becoming a bit too obvious now. Investors are starting to see central banks and Governments as the magic money fairy that always intervene when things start to go wobbly. After all, that’s what’s happened for nearly two decades. There are many investors and brokers and home buyers who have never seen anything but ever-upwards prices punctuated by desperate episodes of central bank money printing and Government interventions to ensure wage earners don’t go without and businesses don’t collapse.

Even our Prime Minister and Finance Minister have acknowledged they would not do anything to force prices down. Both Labour and National believe they can somehow engineer affordability without suburban home owners ever having to see the value of their main financial asset fall, or capital gains or wealth needing to be taxed. They believe that building lots of smaller apartments and townhouses with lower prices will reduce the average price, but not the actual price of suburban homes.

The PM has even said that four percent per annum house price inflation was a sustainable level, which would mean affordability improvements for first home buyers would take decades. That’s great for fertility treatment centres and parents who like their 35 year children living at home, but it’s not great for the birth rate or hopes current generations can have the suburban single family home lifestyle they experienced as children.

The magical thinking is based on voters being unable to understand that affordability improvements are impossible without flat to falling prices, and on the idea proven wrong over the last two decades that housing supply will ‘naturally’ respond to higher prices.

Even the Reserve Bank believed in magic in 2016 and 2017 when it tried in vain to get permission to adopt DTI controls, saying it wouldn’t need to use them because supply would respond.

“The Reserve Bank considers that housing demand and supply will eventually be brought into balance, partly because rising house prices will stimulate housing supply,” it wrote then.

“Work to reduce the costs and uncertainty associated with housing construction by local and central governments should ultimately make it possible to build enough new homes to put downward pressure on house price to income ratios, particularly in Auckland.”

Prices have risen 25% since that hopeful statement and the housing supply imbalance has widened as councils and the Government have been both unable and unwilling to override NIMBY concerns about denser cities and have been unable to override their own officials’ and voters determination to keep the size of Government operations and debt around the average of 30% seen over the last 10 to 20 years.

But the spreadsheets don’t lie, and even the Reserve Bank and Treasury acknowledge that nothing really changes with supply restrictions and the inability to tax housing wealth. In the last three months they have both forecast further house price inflation of another 20-25 percent over the next three to five years.

That’s despite it being ‘obvious’ to politicians and auction room viewers that it’s impossible for house prices to rise any higher. They too are beginning to believe in the impossible when interest rates stay lower for ever, and voters refuse to allow their politicians to seriously address the huge tax and ‘too big to fail’ advantages of the housing market.

The next test will be the Reserve Bank’s latest attempt to get permission to have and use a DTI tool. Politicians want it to only apply to investors. Magical thinking is becoming a habit.

'Spreadsheets don't.' Really Bernard? Have you not heard of lies, damn lies, and statistics.

Of course, they lie.

Your first bullet point highlights this. The 20% of 1.5t is based on price rises caused by a shortage of supply relative to demand. Approx. half that 1.5t is based on non-value-added costs caused by this.

If supply is allowed to meet demand, then a lot of that non-valued added rentier gain will disappear.

But with the artificial jump in price, then the % falls, making it look better than it is. As a metric for determining what is 'good', it has less relevance, ie it has decoupled from being a meaningful measure of performance.

And we know all this and more because, in other jurisdictions where they have had all the same 'reasons' happen to them, their prices have stayed around 3 to 4 x median household income.

Also, I think the issue of council rate increases needed to feed council infrastructure stuff-ups is going to be a drag on the price.

And in the face of climate change virtue signalling, the Govt. are not going to be able to increase the cost to build, or open up the immigration tap like they used to.

Bernard, one issue you could look into, is where the present housing demand is coming from?

Is it all internal NZers, ex-pats, or money coming from the Aussie and Singaporean foreign exemptions?

From what I can tell, the total mid-term demand has not changed. Many sales are off the plan, especially sections and house and land packages, with title and settlement up to 24 months away. This is pulling future demand into the present and thus those people that would have been buying in 24 months under a more stable environment have bought today, which bumped up today's demand and supply imbalance, but also means they won't be around to buy in 24 months time, so will cause a reversal in at that time.