Long stories short, here’s the top six news items of note in climate news for Aotearoa-NZ this week, and a discussion above between Bernard Hickey and The Kākā’s climate correspondent Cathrine Dyer:

The Government announced changes to the Fast-Track Approvals Bill on Sunday, backing off from the contentious proposal to give final say on development projects to just three government Ministers. Instead they now propose to allow the expert panel (selected by a government-appointed convenor) to make the final determinations. That change may appear substantive, but critics argue that it is a classic 'bait and switch'.

In the wake of this, we ask whether the standard ‘public submissions’ approach to such powerful legislation does sufficient service to deliberative democracy? What would a genuinely responsive consultation process look like?

Academics James Dyke, Robert Watson and Wolfgang Knorr deconstruct climate double-speak in this must read article in The Conversation UK. They argue that the concept of ‘overshoot’ and the ‘net zero’ Paris approach are increasingly detached from reality and have become more like science fiction.

A new global stocktake study evaluated 1500 climate policies implemented over the last 25 years identified just 63 successful interventions. Collectively, these policies reduced emissions by between 0.6 billion and 1.8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) We emit over 35 billion tonnes globally every year.

In NZ chart of the week, there’s a startling look at actually how much gross emissions are expected to fall here, and where the real burden lies; and,

In global graphic of the week, there’s a new type of climate stripes.

(See more detail and analysis below, and in the video and podcast above. Cathrine Dyer’s journalism on climate and the environment is available free to all paying and non-paying subscribers to The Kākā and the public. It is made possible by subscribers signing up to the paid tier to ensure this sort of public interest journalism is fully available in public to read, listen to and share. Cathrine wrote the wrap. Bernard edited it. Lynn copy-edited and illustrated it.)

1. Ministerial override removed - but watch for the ‘bait & switch’

On Sunday, the coalition government announced five proposed changes to Fast-Track legislation in response to public submissions.

The headline change dilutes the concentration of power whereby three government ministers were to have the final say over development projects, with power to overrule an expert panel. Under the new proposal, the expert panel will have the final say.

While some critics are satisfied that their concerns have been heard, others are pointing to the landing of a predicted bait and switch, as Fox Meyer reports;

“On the first day of oral submissions for the fast-track bill, Forest & Bird’s chief executive Nicola Toki warned of a bait and switch: “Removal of ministerial override is meaningless unless environmental protections and public participation in existing legislation is retained. I want to make that really clear: that can’t be the only thing.”

Other submitters pointed to legal vulnerabilities, Treaty obligations and a lack of environmental provisions as their chief concerns.“ Newsroom

The overarching aim of the bill is to facilitate economic development, but the failure to include any environmental consideration in the Bill’s framing was highlighted during oral submissions, including by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Simon Upton, whose concise and impactful submission you may recall.

Upton said the bill posed “significant risks to the environment”, comparing it to the Muldoon government’s similar – and deeply unpopular – legislation: “Even the much-maligned National Development Act 1979 had more environmental checks and balances.” Upton didn’t hold back, writing that the bill would “achieve sub-optimal outcomes through poor decision-making, poor allocation of resources, a lack of legislative durability, and increased litigation risk.” The Spinoff

Beyond scrapping the role of ministers as final decision-makers, and elevating environmental considerations in the process, Upton also said that project eligibility should be restricted to those that provide significant public benefits rather than private gains alone. Neither of those recommendations, nor the Auditor-General’s urging for the inclusion of better tools for managing conflict, have been meaningfully taken up.

2. Is the public submissions approach fit for purpose?

The Fast-Track Bill attracted a high number of submissions, some 27,000 from individuals and organisations.

However, a recent study of submissions to the Auckland 2050 plans showed huge demographic asymmetries (older, wealthier, Pākehā voices were loudest) .

The process is also largely one way, with no assurance that policymakers will make adjustments that are in any way scaled to the size or seriousness of the public response.

Koi Tū, The Centre for Informed Futures, housed at the University of Auckland, has been looking at alternative models for holding complex public conversations, resulting in this analysis for the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO). The role of citizen assemblies in complex decision-making is growing internationally and has seen some early success here.

Where the current coalition Government shows no sign of deepening public involvement in policymaking (rather, the opposite), we see enormous potential for a broad expansion in the number and types of public conversations we have about complex issues ahead of the next election, but we desperately need to equip people with the tools and opportunities to have them.

3. Time to get real

On the subject of critical conversations – there is a ‘must read’ one in The Conversation UK this week on the overshoot myth.

Academics James Dyke, Robert Watson and Wolfgang Knorr use plain language to address the dissolution of the Paris Agreement’s aims into failed framings designed to ‘work-around’ the need to reduce fossil fuel use, the failure of any country to strengthen its pledges at the last three COPs while emissions continued to grow, the warning signs we have ignored including the record temperatures over the past two years (that we cannot fully explain) and the looming threat of failing natural carbon sinks and climate tipping points. Instead, we have implicitly accepted overshoot scenarios that rely on science fiction solutions to rectify the situation sometime in the future.

“It’s clear that the commitments countries have made to date as part of the Paris agreement will not keep humanity safe while carbon emissions and temperatures continue to break records. Indeed, proposing to spend trillions of dollars over this century to suck carbon dioxide out of the air, or the myriad other ways to hack the climate is an acknowledgement that the world’s largest polluters are not going to curb the burning of fossil fuels.

Direct Air Capture (DAC), Bio Energy Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), enhanced ocean alkalinity, biochar, sulphate aerosol injection, cirrus cloud thinning – the entire wacky races of carbon dioxide removal and geoengineering only makes sense in a world of failed climate policy.” The Conversation UK.

The article cuts through climate double-speak to debunk claims such as Exxon’s call to use carbon capture and storage (CCS) to produce net zero hydrogen from fossil fuels, pointing to the recent exposure of industry-wide greenwashing on CCS. They also highlight the folly of relying on large-scale BECCS in IPCC pathways that stay below 2˚C, despite clear evidence that it would have very “adverse effects on biodiversity, and food and water security given the large amounts of land that would be given over to fast growing monoculture tree plantations.” As we reported last week, the burning of biomass appears to be increasing carbon dioxide emissions at the moment, with the UK’s Drax biomass power station producing four times as much carbon dioxide as the country’s largest coal-fired station, despite millions in emissions trading scheme subsidies.

Dyke, Watson and Knorr make four suggestions: 1) Leave fossil fuels in the ground, 2) Ditch net zero crystal ball gazing targets, 3) Base policy on credible science and engineering (i.e. focus on doing the things we already know work) and 4) Get real!

4. Taking of stock of what has worked

While global climate policy approaches appear to have largely failed, there is a small subset of policies being implemented by countries that have proven successful in reducing emissions.

A new global stock-take study evaluated 1500 climate policies implemented in 41 countries across six continents over the last 25 years, identifying just 63 cases in which large emissions reductions materialised as a result of policy action (including in Aotearoa).

The amount of emissions reduced by these policies is modest – collectively between 0.6 billion and 1.8 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) over the entire study period (we emit over 35 billion tonnes of CO2 globally every year), so a gradual adoption of these climate policies will not suffice.

However, the insights generated by the work should provide building blocks that inform future paths.

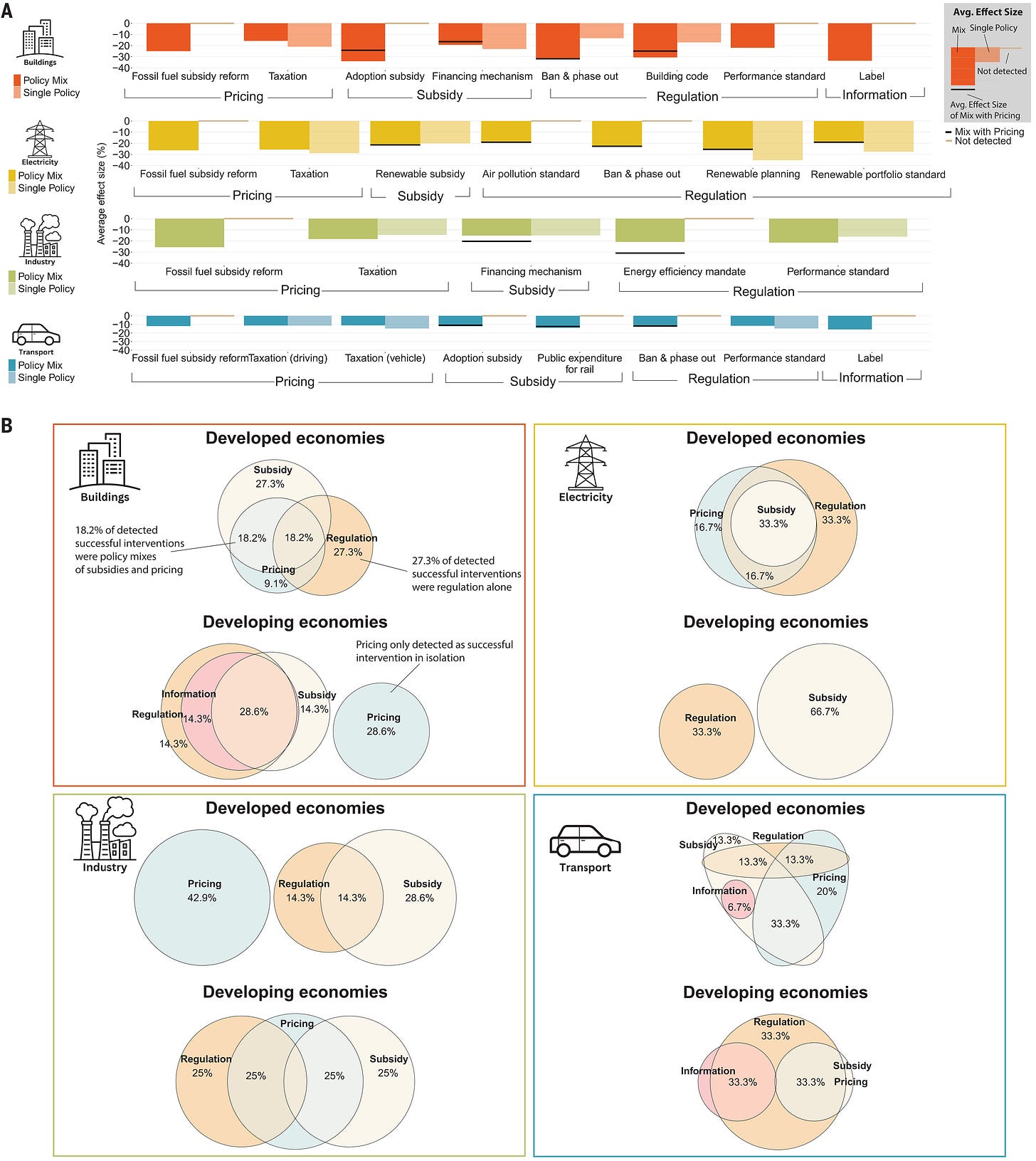

The study, which used machine-learning approaches to analyse data, found an important role for market- or price-based mechanisms within ‘well-designed policy mixes’ in developed countries, with a stronger role for more regulatory approaches in developing countries.

While the importance of sector-based strategies and mixed policy approaches have been pointed out before (it was mentioned in the latest IPCC working group III report), it has been difficult to assess which combinations of policies “effectively unfold complementarities” to deliver stronger emissions reductions. This is the first study that has been able to empirically evaluate mixes of multiple, simultaneously combined policy instruments.

Of the successful policy interventions identified, 24 were in the building sector, 19 were in transport, 16 in industry and 10 cases were in electricity sectors.

Effective Policies and Policy Mixes

Fig. 4. Effective policies and policy mixes from the paper Climate policies that achieved major emissions reductions: Global evidence from two decades

(A) On the basis of point estimates for country-specific breaks in emissions (tables S12 to S19), we compared the average effect sizes of all breaks in which a policy instrument appears individually with that of all breaks in which this policy instrument appears in a mix. For non–price-based policies, the black thick line also indicates the average effect size of a mix with a given policy instrument and pricing (through taxation or reduced fossil fuel subsidies). (B) Euler diagrams (SM materials and methods) show which combinations of policy types [definitions of categories are provided in (A), x axis] are effective in each sector separately for developed and developing economies. For each circle area, the percentage indicates which share of successful interventions in this sector was made up by a specific individual policy type or a specific combination of policy types. An individual policy type encompasses breaks that match a single policy instrument (for example, one subsidy scheme) or a combination of policy instruments of the same type (for example, two or more different subsidy schemes).

5. NZ chart of the week

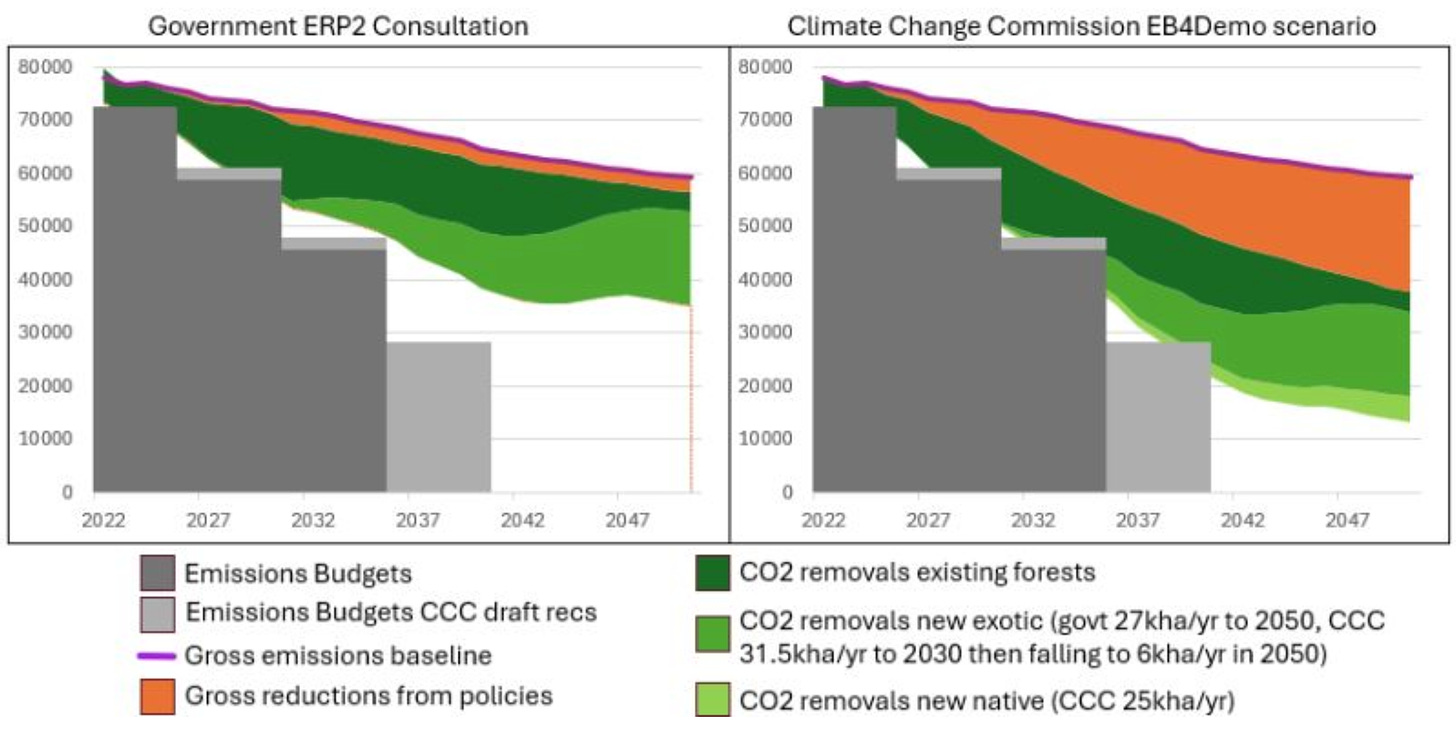

Submissions have now closed on the Government’s ERP2 consultation, but just before they closed, climate policy and carbon market expert Christina Hood shared these charts on LinkedIn, showing just how few gross emissions reductions (the orange part) are planned compared to the Climate Commission’s central (i.e. not most ambitious) scenario. It should be noted that most of the orange you can (just barely) see in the Government’s EPR2 proposal (on the left) is based on an assumption about CCS potential.

According to Hood “In the government's path, if ambition on gross reductions stays the same, to meet the third budget new forestry planting between now and 2030 would need to be double what is suggested (i.e. 54 thousand hectares per year (kha/yr) rather than 27kha/yr).”

The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE) has just released details of their submission on the plan. In short, the submission criticises the ‘least-cost approach’ for risking passing on significant costs to future generations, over-reliance on the ETS, and lack of policy coherency. They recommend:

forestry be decoupled from the NZ ETS, with alternative incentives applied to drive afforestation

a much greater margin of error be built into the emissions budgets

delivery of an Energy Strategy to address long-term issues in the energy sector

greater support for existing and affordable emissions reduction technologies in transport, energy and agriculture

an aviation departure levy on all flights out of New Zealand be imposed to fund possible solutions for aviation emissions

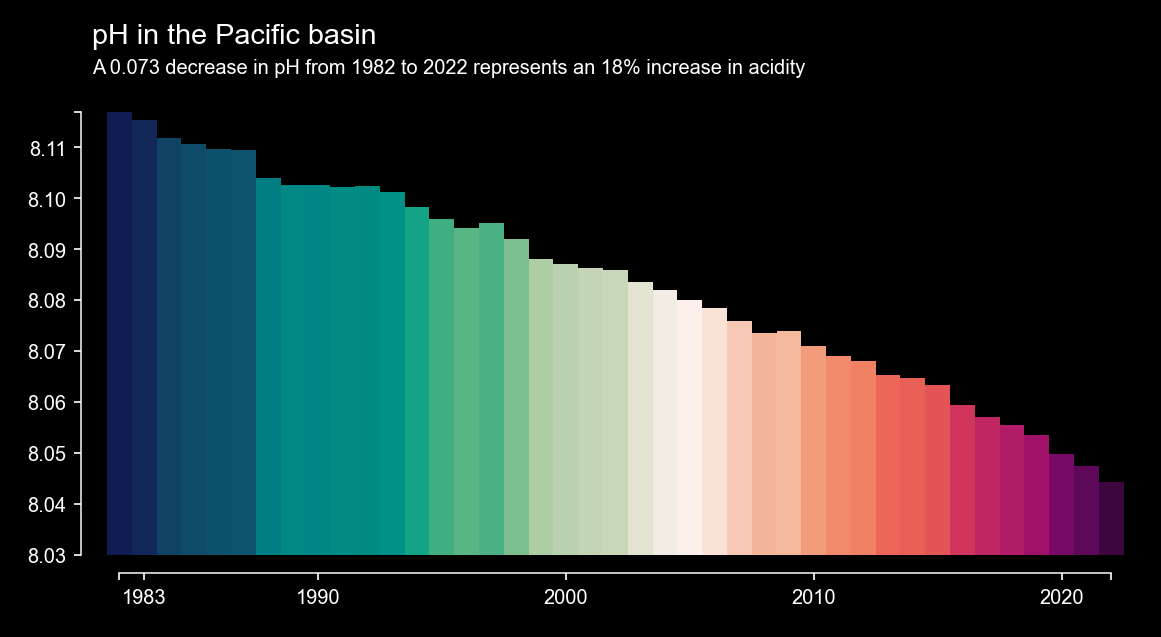

6. Global chart of the week: The Pacific Ocean’s acidification stripes

We spoke last week about ocean heating and some of the effects it was having, noting in passing that the oceans absorb about 25% of the carbon dioxide released as a result of human activity. As most readers will be aware, that carbon dioxide is causing ocean acidification, and you can see just how much from both a global perspective and across various marine ecosystems and ocean basins at this website. The chart below shows the ocean acidification stripes for the Pacific Ocean. Even if carbon dioxide emissions were not causing global warming, we would still need to rapidly phase out fossil fuels because of their effect on another planetary boundary, ocean acidification.

Ka kite ano

Bernard and Cathrine

Share this post