Dawn chorus Thurs Nov 5

PM has $20b to use in 'acceleration' plan speech today; But it could be much more if Labour chose to go beyond Treasury's current debt peak of 56% of GDP; FYI, the IMF is begging for fiscal stimulus

TLDR: In which I argue the case for the now-all-powerful Labour Government to flick the switch on much bigger fiscal stimulus for infrastructure and social spending because borrowing costs of 0.5% are vastly below expected growth rates of 2.5% in years to come. A debt of well over 50% of GDP can easily be serviced and repaid from the existing income and GST tax rates and revenues the Government will reap in from the even faster growth rates created by the productivity boost from that spending.

Don’t take my word for it. This is exactly what the IMF begged us and other Governments to do this week because central bank money printing and bond buying is simply inflating the money supply that is being stashed in bank accounts and existing assets, rather than stimulating the actual economy. Now is the time to borrow big and spend big, the IMF is saying, and it used to be the biggest proponent of tight budgets.

PM set to outline Labour’s agenda for 2020-23

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern will deliver a luncheon speech to a business audience today in Auckland that she has previewed as outlining the new one-party-government’s agenda for an acceleration of its recovery efforts before Christmas. Her new cabinet meets for the first time tomorrow after being sworn in.

I asked her in a news conference on Monday what policies or spending the Government might accelerate in this speech. She wouldn’t give details and instead pointed me to Labour’s five point plan for recovery in its manifesto (pages 5-8), which brings together the first-term Government’s announcements and included:

Retraining subsidies. Higher subsidies for retraining, including free apprenticeships for the next two years, reinstating the Training Incentive Allowance for some courses for disabled and sole parent beneficiaries, increasing the abatement threshold for beneficiaries to $160/week and increasing the ‘flexi-wage’ scheme of wage subsidies for workers at risk of long term unemployment from 6,000 workers to up to 46,000.

Infrastructure investment. Nearly $16b in spending on roads, railways, schools, hospitals, housing and clean energy. That includes $3b from the Provincial Growth Fund announced in 2017 but not spent, $8b in the NZ Upgrade programme announced in January but not spent, $3b announced in April for ‘Shovel Ready projects’ but not spent, $750m for new infrastructure that has not started, and $1.1b for the ‘Jobs for Nature’ fund (of which $132m had been contracted by October 26 and $297.5m is expected to be contracted by end of November. Corrected after I earlier wrote it had not been started. My apologies. Since corrected again after incorrect figure supplied). Overall, the Government said it has $42b available for infrastructure investment over the next four years, but said in October before the election it only had $7.8b available in the current three-year term for new unspecified investment decisions. That is the scope of the infrastructure funding in Labour’s kitty if it sticks to its election manifesto. It also has $12.1b up its sleeve in the ‘Covid Response and Recovery Fund’ (CRFF). So the pot of spending the Government has to play with for today’s ‘acceleration’ announcement is around $20b over the next three years.

Climate change policies. Including targeting 100% renewable electricity by 2030, investigating a $4b pumped hydro scheme south of Alexandra and unspecified measures to increase takeup of electric vehicles and cleaner petrol car imports.

Helping small businesses. Including extending the Covid-19 Small Business Cashflow scheme from two to five years, including doubling the interest free period to two years, the regulation of merchant payment fees charged by banks, and a study in supermarket competition.

Grow exports. Nothing specific other than seeking new trade agreements and attracting wealthy new business migrants.

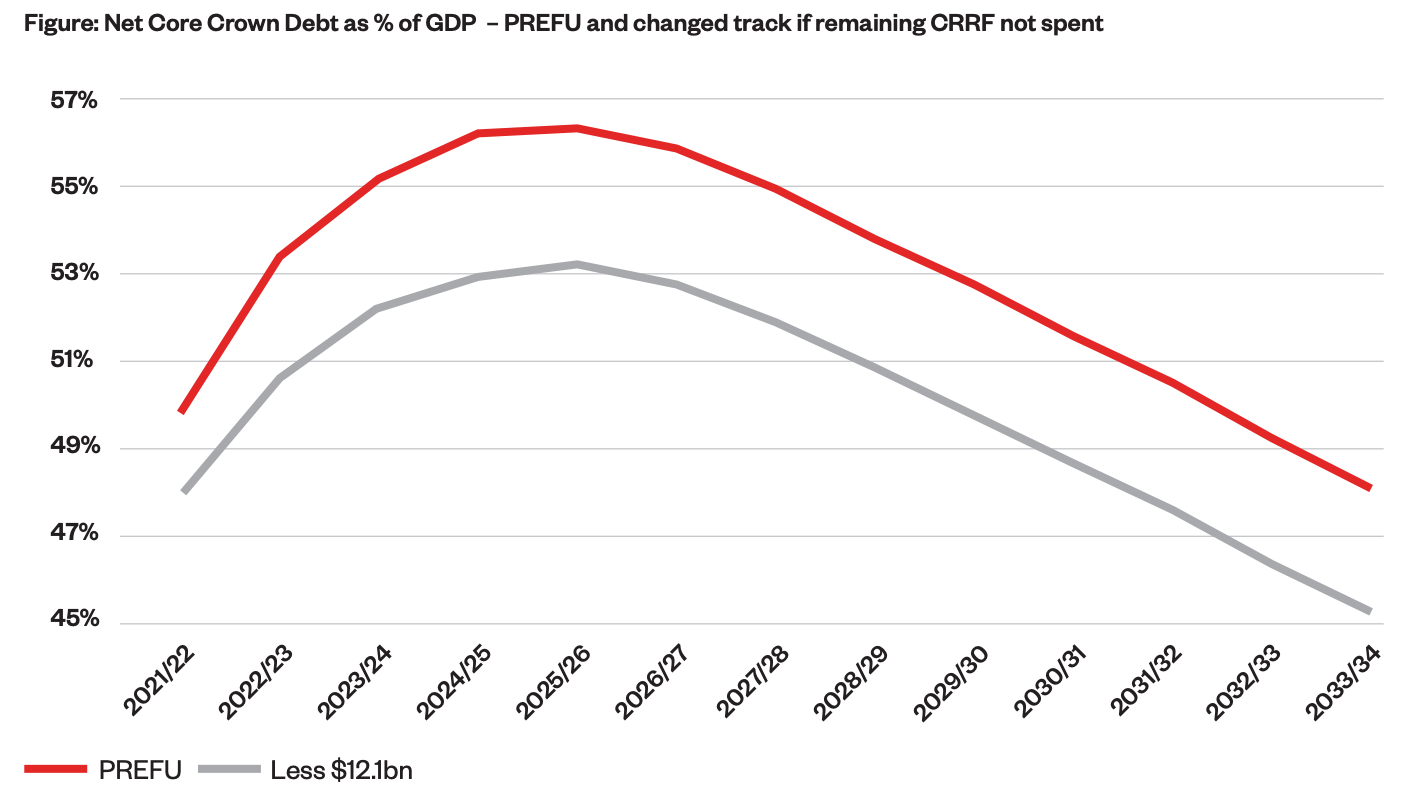

Ardern would have to add some new policies or add new spending to the existing ones to deliver the acceleration she suggested on election night, and previewed in this speech. But she remains hamstrung by Labour’s commitment before the election not to increase the Government’s net debt track beyond the peak of 56% forecast by Treasury in the Pre-Election Fiscal Update (PREFU). Labour even suggested it would not spend the $12.1b still unallocated in the CRRF.

“Labour will take a balanced approach to control and reduce debt while ensuring all New Zealanders have the health, education, and other essential services that they rely on,” Labour said in its manifesto.

Both Ardern and Robertson emphasised their fiscal conservatism before the election. Here’s an example from that manifesto. I think this is what they really think, and they’re dead wrong. The bolding is mine :

“Without a sufficient financial buffer, our ability to manage the negative effects of the pandemic would very quickly become much more difficult. It is a sign of a responsible government that it does not spend its reserves on things that will have only a short-term impact.” Labour

Here’s the chart they included in their manifesto.

Why so timid Prime Minister?

Ardern and Robertson have painted a dark picture of New Zealand’s ability to borrow if there is another earthquake or pandemic shock, but that’s just not true, as evidenced by the demand for New Zealand Government bonds during the Covid-19 shock and the way bond yields have fallen sharply. It also overlooks that since March all of those bonds (and more) have ended up on the books of the Reserve Bank, which is inventing the money to buy them in its Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) programme of so-called Quantitative Easing (QE).

The Treasury has issued $23.7b of new bonds since March 26 at an average weighted yield of 0.56%. That extremely low yield is because there were bids from fund managers and banks totaling $66.9b for those bond issues: almost three dollars bid for every one offered.

Meanwhile, shortly after those bonds were issued in the ‘primary’ market, the Reserve Bank has gone out into the secondary market and bought $37.2b of Government bonds and $1.5b of local Government bonds since March 25. Over that period the Local Government Funding Agency has issued just $1.2b of bonds on behalf of Councils. So our Governments have borrowed $24.9b of bonds, and the Reserve Bank has printed $38.7b to buy those same bonds and an extra $13.8b for good measure.

That means for every $1b the Government has borrowed from investors through bond issues, the Reserve Bank has printed and bought $1.55b. Ostensibly, the Reserve Bank is not doing this to help out the Government. It is doing it to lower long term interest rates to try to fire up inflation and support jobs. That’s because inflation is threatening to break below the 1-3% range the Reserve Bank has to target. But it is very helpful and the Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr and Grant Robertson are rightly working very closely to coordinate their efforts with this type of unconventional policy.

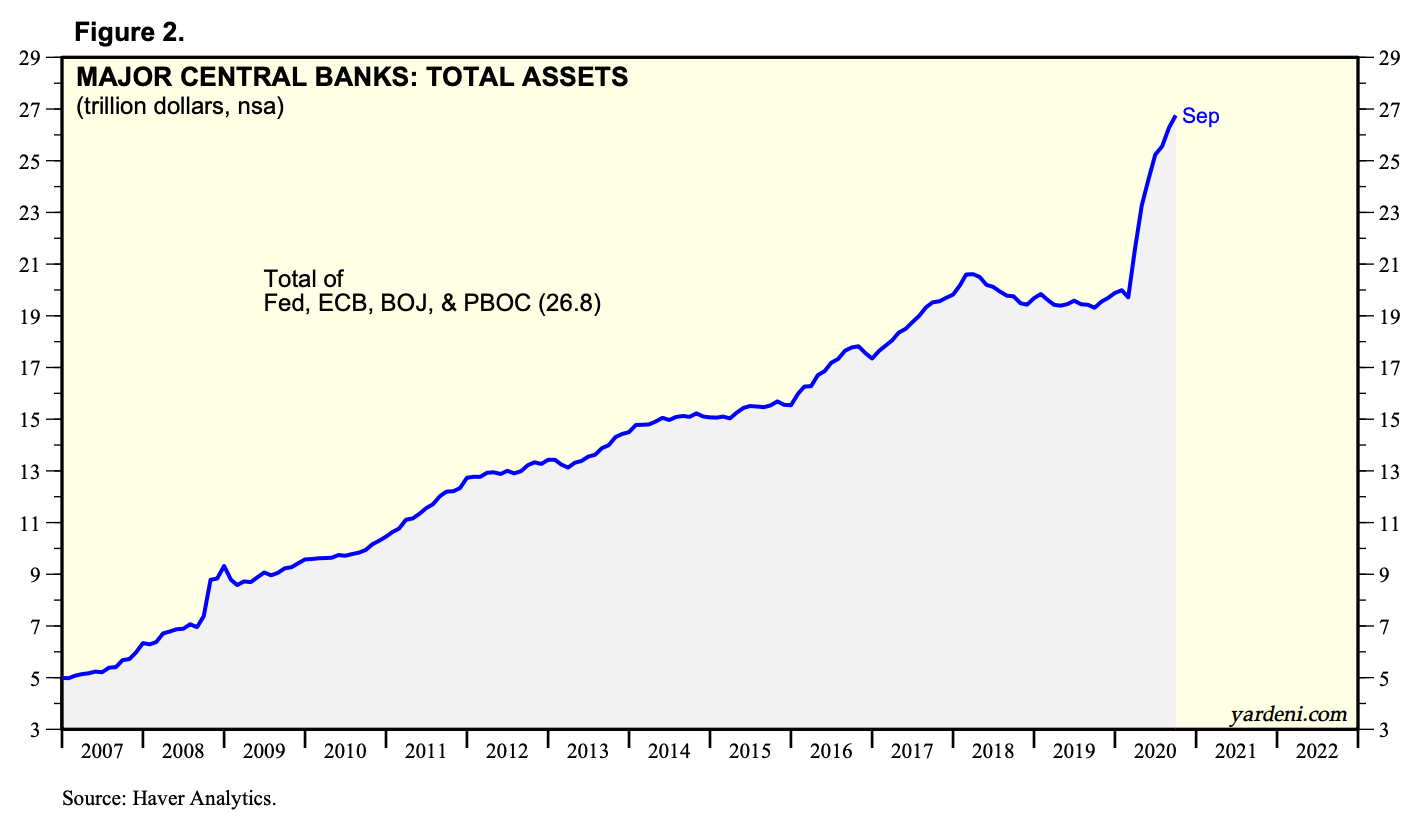

There are absolutely no borrowing constraints on both central and local Government as the moment. There is a mountain range of demand and cash sitting in the global financial system because central banks have printed US$27t (t for trillion) since 2007, including US$8t since March, and that cash is sitting in bank accounts desperate to be invested in Government bonds, which banks and pension funds are often forced to buy by regulators and their fund mandates. It has to go somewhere and wants to come here.

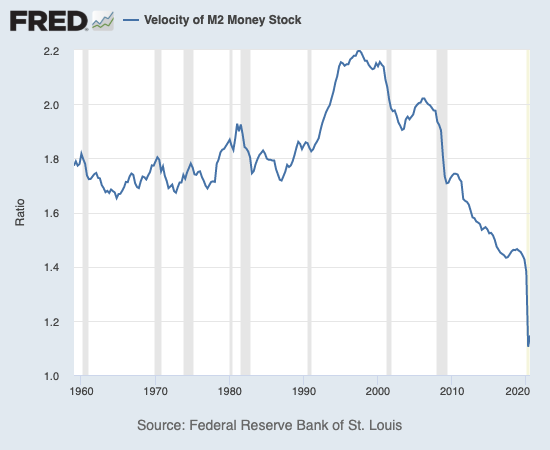

Here’s a Yardeni chart showing the combined money printing since 2007. Below that is a Federal Reserve chart showing how the speed of circulation in the US economy has slowed down. Essentially, the money being printed is not catching fire after fluttering to the ground as we expected. That’s because it’s not being distributed widely to consumers and businesses.

Instead, it was never unwrapped from the bundles packed in plastic on pallets and figuratively rolled into warehouses. It is still sitting wrapped in plastic in the vaults of banks and central bank settlement accounts, in electronic terms at least. This is called a liquidity trap. It may as well be called giving a few old, rich people lots of cash and then being surprised when they choose not to spend or invest it, because their main aim is wealth preservation, not creation, and lowering their risks. Government bonds are low risk because they are confident about being repaid by a Government with the power to tax an entire economy. Investing in new privately created factories and projects and jobs is riskier.

That’s the story of the last decade and helps explain low inflation and low productivity growth. The money is being stored and hoarded, not invested. You can tell that from the speed at which the money is circulating. See more on that in the chart below.

Even the IMF wants much, much more stimulus

There are no signs of inflation breaking out anywhere in the world and global bond investors are essentially betting on virtually no inflation for decades to come. The biggest ‘grown up’ of the global debt markets, the IMF, said this week that Governments should use their balance sheets to borrow and spend on their people and infrastructure to take some of the load off central banks, who appear to have exhausted their firepower (although they have no limit on how much they can print). Ironically, they are being forced to flog the dead horse of inflation because politicians are either unable to too afraid to spend big, often because they need to get elected in much shorter timeframes than the investment cycles and payoffs of such big projects.

But don’t take my word for it

Check out what the biggest ‘grownups’ in the global financial markets are saying now.

IMF Economist Gita Gopinath wrote in the FT this week that Governments with relatively low debt loads should step up and give money to citizens and spend on infrastructure to increase demand and spending. That’s because all the money is just sitting in settlement and bank accounts doing nothing. It is not circulating. (See the chart above on money velocity for more on that) Here’s Gopinath below. Again, the bolding is mine. I’ve quoted at length because the article is paywalled (and I bet the FT didn’t pay her for the column…and it’s worth seeing exactly what the world’s most informed and respected (and usually very conservative) experts are saying.”

“Fiscal policy must play a leading role in the recovery. Governments can productively counter the shortfall in aggregate demand. Credit facilities installed by monetary authorities can only assure the power to lend but not to spend, as US Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell has noted.”

“Fiscal authorities can actively support demand through cash transfers to support consumption and large-scale investment in medical facilities, digital infrastructure and environment protection. These expenditures create jobs, stimulate private investment and lay the foundation for a stronger and greener recovery. Governments should look for high-quality projects, while strengthening public investment management to ensure that projects are competitively selected and resources are not lost to inefficiencies.”

“Many economies can lock in historically low interest rates now and keep debt servicing costs low. The IMF’s latest projections are for economic growth to increase at a faster rate than debt service costs in many countries — and by an even bigger margin in absolute terms than before the pandemic.

This implies that debt service costs could fall. That would provide room in many economies for investment in inclusive, strong and sustainable growth, without compromising debt sustainability or bond market access. The importance of fiscal stimulus has probably never been greater because the spending multiplier — the pay-off in economic growth from an increase in public investment — is much larger in a prolonged liquidity trap. For the many countries that find themselves at the effective lower bound of interest rates, fiscal stimulus is not just economically sound policy but also the fiscally responsible thing to do.” Gita Gopinath

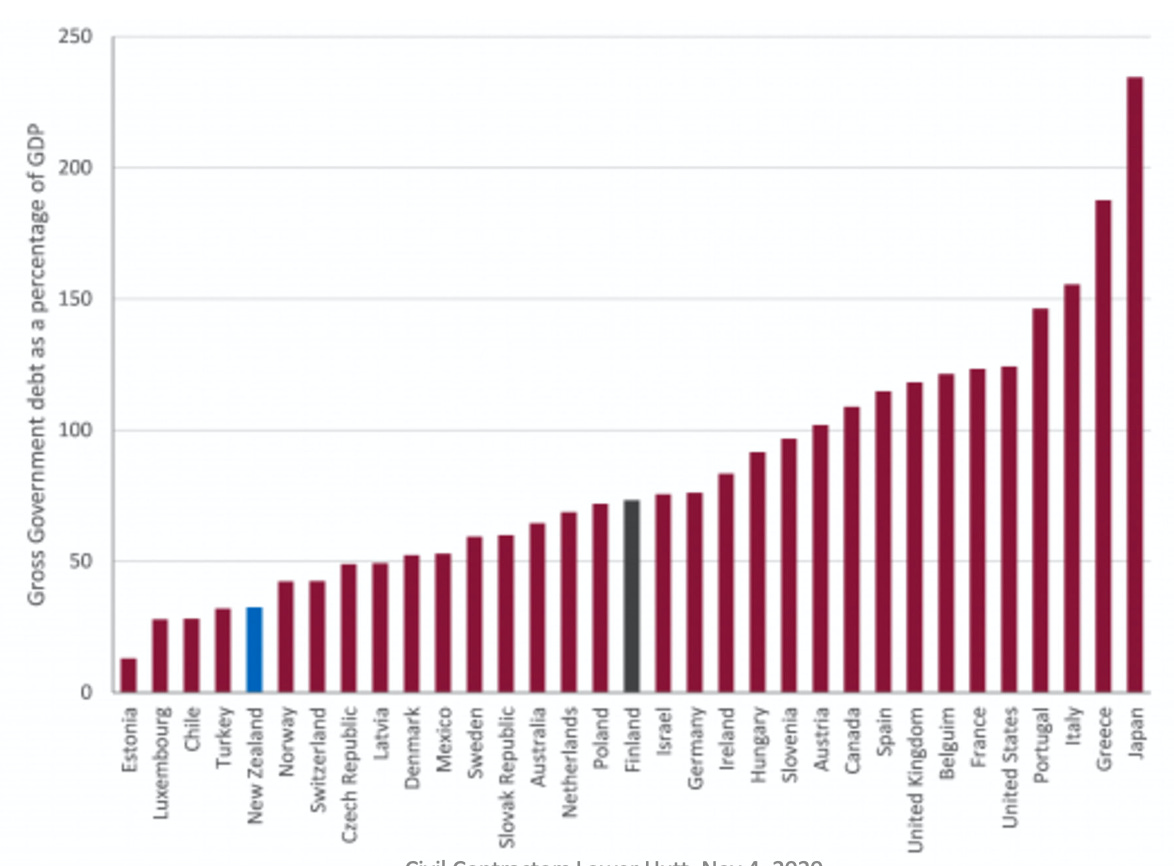

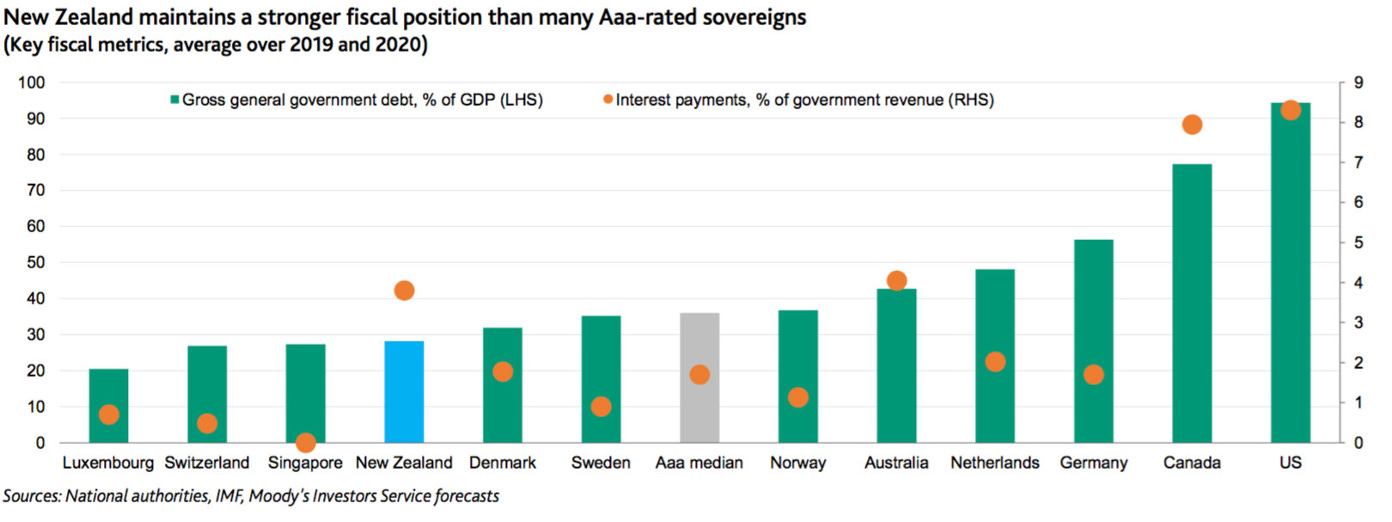

And our debt is already very low compared to the rest

The other reason why the fiscal conservatism of Ardern and Robertson is misplaced is New Zealand is in a much better position than not only the rest of the developed world, but the rest of countries in our AAA debt rating category. If bond market vigilantes are going to punish anyone, it won’t be us.

There are now many, many more in the queue ahead of us. If anything, any withdrawal of funds from risky economies will be redirected to those economies with lower debt, better growth prospects, growing populations and a great Covid-19 performance. That is New Zealand. Here’s the charts to prove it. The first one shows our debt levels vs all developed countries. The second shows our debt levels vs other AAA-rated countries.

‘Believe in yourselves and the rest of us’

The Prime Minister and the Finance Minister should be more confident and less worried. It’s understandable when you have spent your entire political lives being told about how ‘bad’ Labour is at running the economy and of the political and economic dangers of borrowing too much and investing big lumps in Government projects and spending programmes. It wasn’t true then, by the way, but is even less true now.

This caution is also understandable when for their whole political lifetimes the only way to govern has been in coalition with other parties who had the power to veto big plans and ideas. MMP was designed to squash big Government policies and changes, and has done just that since 1996. Labour’s first term illustrated that perfectly, with Labour’s proposal for a Capital Gains Tax and its hopes for a Light Rail project nixed by New Zealand First, and its road investment plans hampered by a Green preference for public transport that bogged the NZTA down in a major strategic rejig.

But that was yesterday. Ardern and Robertson won the trust of voters on October 17 in a way that has delivered them unprecedented power under MMP with 65 or 66 seats in a 120 seat Parliament. We have no second chamber or activist Supreme Court. Ardern and Robertson are supreme in their cabinet and their caucus. They now have an elected dictatorship of sorts, and promising to repair our infrastructure deficits and turn around 30 years of worsening social conditions for nearly half a million people is not abusing the privilege. It is doing the right thing financially, socially and politically.

Surely they can find ways to spend $100b or more over the next 10 years that would generate extra economic growth above the 0.5% cost of borrowing in our own currency that they could easily lock in right now? It would give our construction and business sectors enormous certainty to invest in equipment and their people, knowing those plans aren’t going to be gazumped by a change of Government or Winston Peters changing his mind.

Trust yourselves and us to give it a crack. You might be surprised.

I’ll leave it there for now and report back after the speech, which I’m attending in Auckland.

Here’s some light election relief (boy, we need it after the last 24 hours) from my twitter doom scrolling…

Have a great day

Kia Kite Ano

Bernard

PS: Another great pic from Paul on Rakiura today. I welcome fresh ones. I have no problems with product placement, if you can convince the kākā to sit still for long enough…