TLDR: Te Pūtea Matua (RBNZ) ploughed ahead this week with its own review of its own performance over the last five years, rumbling over the top of extraordinary criticism from former Reserve Bankers and the Opposition alike to find it largely did what it was it was supposed to do.

The Reserve Bank published 122 pages of self-reflection and analysis to show it mostly got its monetary policy right between 2017 and 2022, along with 24 pages of reviews of the review from two former central bank policymakers from Australia and Canada respectively. I’ve now read them all and have taken a chance to reflect. The reviews all made sense in a narrow almost legalistic view of the updated Reserve Bank Act and the unprecedented actions taken through 2020 and 2021 by the Reserve Bank and its new Monetary Policy Committee with its expanded remit to support maximum sustainable employment.

The review all reads logically and clearly, and despite what was alleged beforehand, it’s no whitewash. But it does leave several areas only lightly addressed, including the removal of LVRs for almost a year. It also does not address the monumental inter-generational shift in wealth from younger renters to older property owners caused in 18 months by the combined actions of the Government and the Reserve Bank.

The central bank might argue that preventing a widening of inequality is not it’s job. But that failure to address the elephant in our political economy only deepens the disconnection between the institution that worsened inequality the most in our history, and the people it needs to win back the trust of: the young renters who now see little real future to build secure and healthy families in Aotearoa.

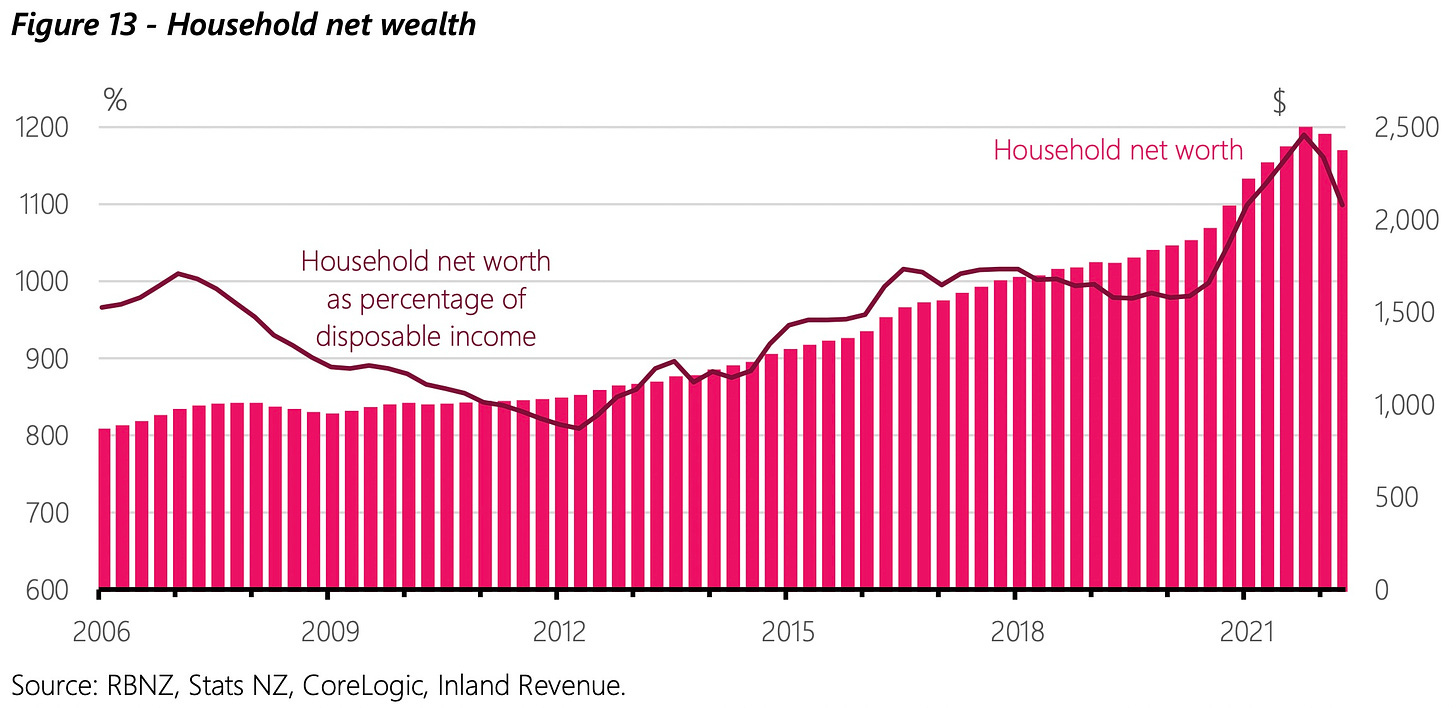

This chart below was included in the review, but there is no acknowledgement of the shock of 2020 and 2021 in wellbeing and social stability, other that to say the Reserve Bank knew it has to use the ‘wealth effect’ to boost the economy and that growing inequality had been one of the reasons over the last five years for falling structural interest rates. But that’s the extent of it.

For me, this is the fundamental failure of this review and, ultimately, of the Reserve Bank and Government actions through covid. They knew that their ‘least regrets’ policies of money printing, relaxed lending rules and subsidised lending for banks would boost house prices substantially and Finance Minister Grant Robertson was advised it would widen inequality. But they went ahead anyway and didn’t understand just how explosive that would be, and then when it happened, have not addressed it as either a problem or something that should never be allowed to happen again.

In my view, this review failed to address the elephant in our political economy, and in doing so, has left open the risk it uses those same extraordinary tools again to achieve its monetary policy goals. It also fails to acknowledge that using those tools without the express permission of the public at large through both sides of Parliament has eroded the Reserve Bank’s social license. The extreme threat and speed of covid made that request for permission impossible, but there was an opportunity with this review to at least address it, if not talk about the need for someone else to.

There’s a saying the likes of Uber and Facebook used in their pirate-like growth phases: “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.”1 During covid, neither the Finance Minister or the Reserve Bank Governor were able or chose to ask the public or Parliament for permission, and they appear unable and unwilling now to ask for forgiveness.

They lit the fuse on a bigger-than-expected bomb

About a decade ago I started half-joking that we didn’t have a real economy, we had a housing market with bits tacked on. It’s a slightly rude thing to say about a modern economy, even a small one without much manufacturing and without deep connections to the global economy. I used to say it to make a point and to provoke a discussion, but it felt more and more true as time went on.

But I’m not the only one to know that our inelastic housing supply combined with the inherent advantages of tax-free and leveraged capital gains mean that any increase in demand from population growth or lower interest rates would have a disproportionate effect on house prices. The Reserve Bank and Treasury had researched and written for over a decade that supply constraints and the lack of a capital gains tax meant that any increase in demand turned into super-heated gains in prices. That’s why the Reserve Bank eventually had to impose and then tighten its Loan to Value Ratio (LVR) restrictions from 2013 onwards.

So when the Reserve Bank decided it needed to stimulate massively, it reached for the ‘wealth effect’ lever knowing it would have some sort of impact. It was advised it would increase house prices dramatically, but it could not have imagined the combination of $55b of money printing, the removal of the LVRs and then $16.4b of subsidised lending to banks would increase house prices 45% in 18 months.

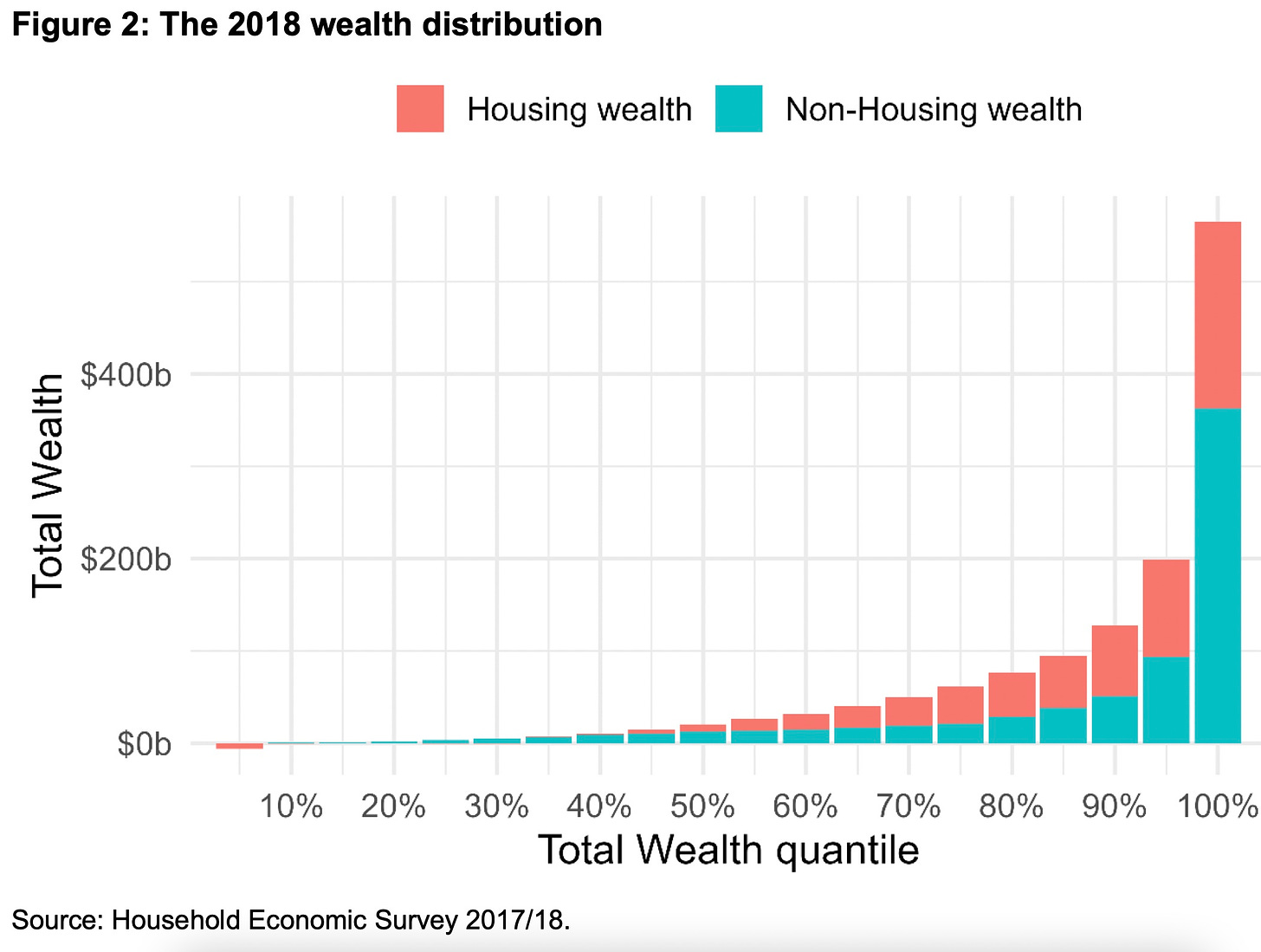

It also knew that the house price inflation over the previous 20 years had already skewed wealth in Aotearoa away from young renters, Māori and Pasifika to older, home-owning Pakeha. It knew its actions would worsen this.

The covid response made this wealth shift worse

The review does not touch on this or the effects on the trust the Reserve Bank requires of the public to do its job. Trust is not only about credibility of actions, but of intent and fairness. If the public don’t believe in the Reserve Bank’s ability to keep inflation low and the financial system stable, then the currency, the financial system and the economy generally is vulnerable to instability. If the public believes the Reserve Bank doesn’t care about the effects on wealth and future for young renters, that will undermine trust too.

One symptom of that is dropped quietly into page 99 of the review (bolding mine):

“A survey recently commissioned by the Reserve Bank also raised questions about the likelihood of inflation returning to the target band by 2024. The survey (from a representative sample of 1,000 people) showed that the majority had little or no confidence in the Reserve Bank’s ability to bring inflation within the target band by 2024.” Reserve Bank review (page 99)

The rights and wrongs unpacked

The review does admit mistakes, including:

the Reserve Bank should have stopped money printing earlier than mid-2021 and started rate hikes earlier than October 2021;

it should have allowed more flexibility to stop or slow down the Funding for Lending Programme of cheap lending to banks; and,

it could have understood more clearly just how quickly and effective the wage subsidy stimulus would be for the economy.

However, the bank’s clear view is that it could not have responded that much differently, and even if it had done the tweaks suggested above, it would only have dragged inflation’s peak down into the 6% range, rather than the 7% experienced by mid-2022. It even went as far as saying that keeping inflation within the target band of 1-3% now would have required perfect foresight and an OCR in 2020 of 7%.

Here’s the section of the news conference with the briefing where I ask Adrian Orr and Chief Economist Paul Conway about the LVRs removal, the wealth effect and social license. In the end Orr acknowledged that in hindsight, the LVRs should not have been removed. This was not addressed in the review.

In essence, the Reserve Bank doesn’t believe it has done much wrong.

In my view, it has defined its own performance review too narrowly and ignored the very real social license and moral hazard issues that have developed globally around the use of monetary policy tools to make the wealthy wealthier, and to protect those values against falling. In doing so, it took the prospect of home ownership out of the realistic reach of renters without wealth parents, and in the last two years, used those tools in a way that created goods, services and rental inflation that also hurts those who rent the most.

The review ignores the accusation that an independently run arm of the state has accidentally on purpose become the servant and protector of the rentier class, seemingly without being accountable to the people through Parliament.

That’s not the accusation levelled by the Opposition, which is focused more on accountability about CPI inflation, but it is one that should also include the Labour Government and Treasury, which has imposed a 30-year long investment drought that led to the ‘sticky’ housing supply situation.

Ka kite ano

Bernard

A post-mortem on an inter-generational and institutional tragedy